The Nintendo 3DS was supposed to be the next great leap for handheld gaming—a device that bent reality itself with glasses-free 3D. Instead, its debut was closer to a nosedive. A sluggish launch, a barren library, and a price tag that turned excitement into hesitation nearly derailed it before it ever left the station. But out of the wreckage came one of the most remarkable turnarounds in gaming history.

Through bold price cuts, a flood of must-have titles, and a reinvention of its own identity, the 3DS clawed its way back from the brink. What began as a misstep transformed into a system adored for its eclectic library, quirky innovations, and staying power in an age dominated by smartphones. This wasn’t just survival—it was defiance. The 3DS was proof that Nintendo could stumble, recover, and still reshape handheld gaming on its own terms.

A Rocky Road To 3D

Long before the 3DS was a twinkle in Nintendo’s eye, the company had already flirted with the idea of bringing three-dimensional gaming to the masses. The first real attempt came in 1987 with the Famicom 3D System, a chunky peripheral that promised to add depth and immersion to the 8-bit era. It sounded futuristic. In practice, it was more of a curiosity than a revolution.

Using active shutter glasses that synced with the console, the device created the illusion of depth by rapidly flashing alternating images. The effect was novel but exhausting, with visuals that strained the eyes more than they amazed. Even worse, only seven games were ever designed to support it, and none could justify the hassle. Titles like Highway Star (known as Rad Racer in the West) hinted at potential, but the technology simply wasn’t ready for primetime.

The Famicom 3D System was quietly discontinued, remembered mostly as a footnote in Nintendo’s long list of experimental side projects. Yet, buried in this failed gadget was the seed of a much bigger ambition: Nintendo’s obsession with making players see games in new dimensions.

If the Famicom 3D System was a harmless experiment, the Virtual Boy was a full-blown gamble that went terribly wrong. Launched in 1995 under the guidance of legendary designer Gunpei Yokoi, it was billed as the future of immersive gaming—a tabletop console that promised stereoscopic 3D without the need for a TV. In reality, it became one of Nintendo’s most infamous blunders.

The system’s red-only display was its defining quirk and its biggest flaw. The stark monochrome visuals weren’t just underwhelming; they were uncomfortable. Sessions often led to headaches, dizziness, and eye strain, turning excitement into regret. The bulky headset, awkward stand, and lack of true portability only compounded the problem.

Worse still, the library was anemic. While titles like Mario’s Tennis and Wario Land showed flashes of creativity, there was never enough content to justify the machine. Sales reflected this reality—just 770,000 units sold worldwide, making it Nintendo’s worst-performing console by a wide margin.

The Virtual Boy was discontinued within a year, a harsh reminder that bold innovation can sometimes veer into commercial disaster. Yet even in failure, it revealed Nintendo’s unshakable fascination with 3D gaming—a fixation that would eventually find redemption in the handheld space.

Even after the Virtual Boy’s collapse, Nintendo never fully abandoned its dream of 3D gaming. The early 2000s brought fresh experiments—quiet tests that hinted at how close the company was to cracking the code.

On the GameCube, Nintendo actually had a working prototype of Luigi’s Mansion running in full stereoscopic 3D. The idea was dazzling: explore a haunted mansion where ghosts and objects popped from the screen, making every corridor feel alive. The problem? The technology needed a special LCD display that would have doubled the cost of the console. With no affordable way to mass-produce the effect, the feature was shelved.

The Game Boy Advance SP faced a similar fate. Engineers toyed with glasses-free 3D screens long before they were market-ready, building prototypes that hinted at a pocket-sized future. Once again, though, the expense was insurmountable. Consumers wouldn’t pay the premium, and Nintendo wasn’t willing to gamble on another costly failure.

These abandoned projects weren’t wasted work—they were stepping stones. Each attempt taught Nintendo something new, laying the groundwork for the day when 3D would finally become not just a gimmick, but the centerpiece of a successful handheld.

The Birth of the 3DS

The Nintendo DS had already proven that unconventional ideas could reshape handheld gaming. Dual screens, a touchscreen, and a clamshell design turned skepticism into runaway success. But behind the curtain, Nintendo was already thinking about its successor. As early as 2004, engineers began sketching out concepts for a more powerful handheld—one that could push boundaries beyond touch.

The seeds of the 3DS were planted here. StreetPass, that quirky feature allowing systems to silently exchange data when passing another player, was envisioned during these early days. The idea was simple but audacious: turn a handheld into a social beacon, alive even when tucked away in your pocket. At the same time, hardware teams were exploring ways to finally bring stereoscopic 3D to the mainstream, without the awkward glasses or prohibitive costs that had doomed past attempts.

For Nintendo, the DS era wasn’t just about capitalizing on touch controls. It was a laboratory, a proving ground. Every success and failure, from PictoChat to the DS’s Wi-Fi Connection, informed what would become the 3DS—a machine designed not just to play games, but to connect people in ways handhelds never had before.

The real breakthrough came when Nintendo’s R&D teams finally found a way to make 3D feel natural—without the baggage of clunky eyewear. In the late 2000s, experiments began with parallax barrier screens, the kind that could deliver stereoscopic depth to the naked eye. The technology was promising, but it still needed the blessing of one man: Shigeru Miyamoto.

Prototype testing began with a modified version of Mario Kart Wii, rebuilt to showcase glasses-free 3D. The effect was immediate. Karts seemed to leap from the track, shells flew toward the player with startling realism, and courses carried a sense of space that traditional displays couldn’t replicate. It wasn’t just a gimmick—it felt like a new layer of immersion.

Miyamoto’s response was decisive. He saw the potential not only for spectacle, but for gameplay, for giving players new ways to perceive space and timing. His green light meant Nintendo would finally commit to glasses-free 3D as the cornerstone of its next handheld. After decades of failed experiments and half-measures, the company was ready to turn its obsession with depth into a market-ready reality.

E3 2010 – The Big Reveal

By the summer of 2010, whispers of Nintendo’s “next DS” had already stirred speculation. But nothing prepared the industry for the curtain drop at E3. The Nintendo 3DS wasn’t just another incremental upgrade—it was the company planting a flag, declaring that handheld gaming could still surprise.

The hardware alone was a statement piece. A circle pad for smooth analog control. Built-in motion sensors that invited tilt-based play. Outward-facing 3D cameras that could capture the world in stereoscopic depth. And, of course, the star of the show: a top screen capable of glasses-free 3D, adjustable with a simple slider. It was futuristic yet approachable, a toybox of features wrapped in Nintendo’s signature charm.

But hardware is only half the story. What really sent the crowd buzzing was software. When Nintendo announced Kid Icarus: Uprising at E3 2010, jaws hit the floor. The series hadn’t seen a new entry since 1991, and here it was—revived in bold fashion for a brand-new handheld. Alongside it came a parade of heavyweight names—Star Fox, Kingdom Hearts, Street Fighter. Suddenly, the 3DS was positioned as a battleground for portable gaming’s future.

The reveal didn’t just excite—it ignited imaginations. For longtime Nintendo fans, the 3DS promised not only technical wizardry but also a revival of beloved franchises. Star Fox 64 3D was an early highlight, breathing new life into a Nintendo 64 classic with depth that made barrel rolls feel more exhilarating than ever.

Then came Pilotwings Resort, a gentle showcase of the handheld’s strengths. Its skies and islands weren’t just colorful playgrounds; they were proof that the glasses-free 3D wasn’t a fleeting gimmick. Gliding across Wuhu Island carried a sense of presence that no screenshot could capture.

Together, these titles painted a clear picture: 3D gaming had finally arrived, and this time it was here to stay. It was the true heir to the DS throne, a device that would carry Nintendo’s handheld legacy into the next decade. Fans began dreaming big, not only of remakes and revivals but of entirely new adventures that could only exist in this bold, stereoscopic world.

A Shaky Launch

For all the hype it generated at E3, the 3DS stumbled out of the gate. When the system finally hit store shelves in February and March 2011, excitement quickly gave way to skepticism. For many people, the price tag raised alarms. At $249.99, the 3DS entered the market uncomfortably close to home console territory. For perspective, the Wii—a living room staple at the time—retailed for just $50 more. For parents and casual players, that math didn’t add up. Why spend nearly the cost of a console on a handheld, especially one without a killer app?

The sticker shock hit especially hard in Nintendo’s strongest markets. Handhelds had traditionally been the “affordable” entry point into gaming, but the 3DS challenged that expectation. To many, it felt less like a successor to the DS and more like an expensive experiment. Early adopters were left defending their purchase, while the wider audience hesitated, waiting for either a price cut or a clearer reason to buy in.

Even those who did take the plunge at launch quickly discovered the 3DS wasn’t the fully-formed vision Nintendo had teased. The hardware was impressive, but the ecosystem felt half-baked. Most glaring of all: no digital game store. In an era when digital distribution was rapidly becoming the norm, the absence of an online storefront left the 3DS feeling behind the times.

Players had no way to download classic titles, no bite-sized digital experiments, no library beyond the meager selection on store shelves. Nintendo’s clunky friend code system returned, draining the excitement out of multiplayer and making simple connections feel like a chore. Without streamlined social tools or robust matchmaking, the promise of a connected handheld rang hollow.

Only 15 games were available at launch, and few of them carried the weight to justify a brand-new console purchase. Nintendo leaned heavily on Pilotwings Resort and three versions of Nintendogs + Cats (in case one cute puppy wasn’t enough) to show off the hardware, but neither felt like the kind of must-have killer app that had defined the DS years earlier. Pilotwings was charming but slight, while the Nintendogs sequel felt more like a tech demo dressed up with fur and whiskers.

Third-party offerings, meanwhile, were scattershot—titles like Super Street Fighter 4 3D Edition and Ridge Racer 3D impressed in bursts, but nothing screamed system-seller. The early months left players with the sinking feeling that they’d bought into potential rather than reality—and potential doesn’t keep a handheld alive for long.

As if the shaky launch lineup, high price, and missing features weren’t enough, the 3DS faced a new kind of rival—one Nintendo had never truly battled before. Smartphones. By 2011, Apple’s App Store and Google Play were overflowing with cheap, instantly accessible games. Angry Birds, Cut the Rope, Fruit Ninja—bite-sized experiences that cost a few dollars, if not free, were stealing hours of playtime from the same audience Nintendo had captured with the DS.

For parents, the math was brutal. Why spend $40 on a single 3DS cartridge when mobile devices already sitting in pockets could deliver dozens of games for a fraction of the cost? For teens and casual players, pulling out a phone to game was seamless, social, and increasingly stylish.

What was supposed to be a triumphant new era instead looked dangerously close to a flop in the making. Sales trickled, momentum stalled, and for the first time in years, Nintendo’s handheld dominance seemed vulnerable. The DS had thrived because it offered experiences you couldn’t get anywhere else. The 3DS, at least in its launch months, hadn’t made that case convincingly enough—and the rising tide of smartphones was threatening to wash it away before it found its footing.

The Turning Point

By mid-2011, the 3DS was teetering on the brink. Nintendo’s proud history with handhelds was suddenly in jeopardy, and the press was circling. Then came an extraordinary moment of leadership. Satoru Iwata, Nintendo’s beloved president, stepped forward and shouldered the blame. He halved his own salary, while other executives took cuts ranging from 20 to 50 percent. It wasn’t just symbolism—it was a signal that Nintendo’s top brass would bleed alongside the company’s struggling handheld.

The real shockwave came with the 3DS itself. In a move that stunned the industry, Nintendo slashed the system’s price from $249.99 down to $169.99, barely four months after launch. It was a gamble that screamed desperation, but it worked. Suddenly, the 3DS wasn’t an overpriced novelty—it was a must-have gadget again, a handheld that felt within reach of the very audience Nintendo had been losing.

This combination of humility and bold action marked a turning point. Nintendo had stumbled, but it wasn’t ready to give up on 3D—or on the millions of players waiting for a reason to believe.

Of course, slashing the 3DS’s price so quickly created another problem: what about the loyal fans who had already paid full price at launch? Nintendo knew it couldn’t risk alienating its earliest adopters—the diehards who had taken the plunge despite the shaky lineup and high cost.

The solution was the Ambassador Program, a goodwill gesture that offered 20 free downloadable games: 10 NES classics and 10 GBA titles, many of which would never again be made available on the 3DS eShop. It wasn’t just a gift; it was a badge of honor. Early buyers could show off their exclusive digital library and home screen badge, a quiet nod from Nintendo that said, “We know you believed in us first.”

The program wasn’t perfect, but it softened the blow of the price cut and kept the faithful on board. In a way, it turned early adopters into evangelists, carrying the message that the 3DS was finally worth owning—and that loyalty to Nintendo still meant something.

If the price cut cracked the door open for the 3DS, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time 3D blew it wide open. Released in June 2011, this remaster of the N64 classic wasn’t just a nostalgia trip—it was a revelation. Sharper visuals, smoother controls, and the magic of Hyrule reimagined in glasses-free 3D gave players the kind of must-have experience the handheld had been sorely lacking.

Nintendo doubled down with a marketing campaign that tugged at the heartstrings. Commercials starring the late Robin Williams and his daughter, who is named Zelda as well, tapped into something rare: authenticity. Williams wasn’t just reading lines; he was a lifelong fan, sharing the same awe and wonder that players felt when stepping into Ocarina’s world for the first time.

The effect was immediate. Suddenly, the 3DS had a killer app and a story to tell. Combined with its new, lower price point, the console was no longer just a curiosity—it was becoming the handheld everyone wanted to unwrap by the holiday season. Momentum, at long last, was swinging back in Nintendo’s favor.

Just as Ocarina of Time 3D rekindled excitement, Nintendo delivered another crucial piece of the puzzle: the Nintendo eShop. Rolling out in June 2011, only a few months after launch, it finally gave the 3DS a proper digital storefront—a glaring omission that had left early adopters scratching their heads.

The eShop wasn’t just a place to buy games. It was Nintendo’s first serious attempt at building an online ecosystem for a handheld. Players could download demos, watch trailers, and even pick up exclusive digital titles that never saw a retail release. Over time, it became home to Virtual Console classics, quirky indie projects, and bite-sized experiences that made the handheld feel alive between big releases.

Beyond games, the eShop also unlocked video apps like Netflix, Hulu Plus, YouTube, and Nintendo Video, some of which even experimented with 3D content. Suddenly, the 3DS wasn’t just a gaming device—it was an entertainment hub. For a system accused at launch of being light on value, the eShop was a statement: this handheld was built for the future.

Games That Saved the System

If Zelda reminded players why they loved Nintendo, Super Mario 3D Land proved the 3DS could deliver something new. Released in November 2011, it wasn’t just another Mario game—it was the plumber’s first true 3D adventure crafted specifically for a handheld.

The genius of 3D Land lay in its hybrid design. It fused the linear, flagpole-chasing simplicity of the 2D Mario games with the freedom and spectacle of the 3D entries. Levels were short, tightly designed bursts of platforming joy, perfectly suited for handheld play. And for the first time, Nintendo made the stereoscopic 3D more than a gimmick—it actively enhanced gameplay, letting players judge distances, dodge hazards, and spot secrets with surprising ease.

It felt revolutionary: Mario reborn for the pocket-sized era, but without compromise. Reviews were glowing, sales soared, and suddenly the 3DS had its defining exclusive. This was the moment critics stopped calling it a struggling novelty and started calling it the must-own handheld of the generation.

Dropping in December 2011, just weeks after Super Mario 3D Land, Mario Kart 7 became the system’s crown jewel of multiplayer mayhem. Gliders and underwater sections added verticality and variety, while the ability to customize karts gave players more control over speed, handling, and style. Online play, though simple by modern standards, was smooth enough to make global rivalries a regular part of the experience. With over 18 million copies sold, Mario Kart 7 wasn’t just a hit—it was proof that the 3DS could stand tall against smartphones and home consoles alike.

Released in March 2012, Kid Icarus: Uprising wasn’t just a comeback story; it was a showcase of the 3DS’s raw potential. Directed by Masahiro Sakurai, the mind behind Super Smash Bros., the game blended high-speed rail-shooter segments with on-foot combat in sprawling arenas. The stereoscopic 3D gave battles a surprising sense of depth, with projectiles and enemies flying toward players in dazzling fashion. For many, Uprising cemented itself as a fan favorite and one of the most daring titles in the 3DS library.

Pokémon X and Y took the series’ first step into full 3D graphics, and it had a global launch event that made headlines worldwide. The momentum carried forward with Pokémon Sun and Moon, which became some of the best-selling titles on the system and a genuine cultural moment for handheld gaming.

Then there was Fire Emblem Awakening, a title that not only revitalized a nearly dormant franchise but turned it into a modern Nintendo powerhouse. With its blend of tactical gameplay, heartfelt storytelling, and a newfound emphasis on character relationships, Awakening turned casual players into strategists and gave the 3DS a serious prestige hit.

And who could forget Animal Crossing: New Leaf? This was the game that ate hours, days, and months of people’s lives, transforming the 3DS into a pocket-sized town you could check into anytime. Its charm, freedom, and constant seasonal updates made it one of the defining experiences of the console.

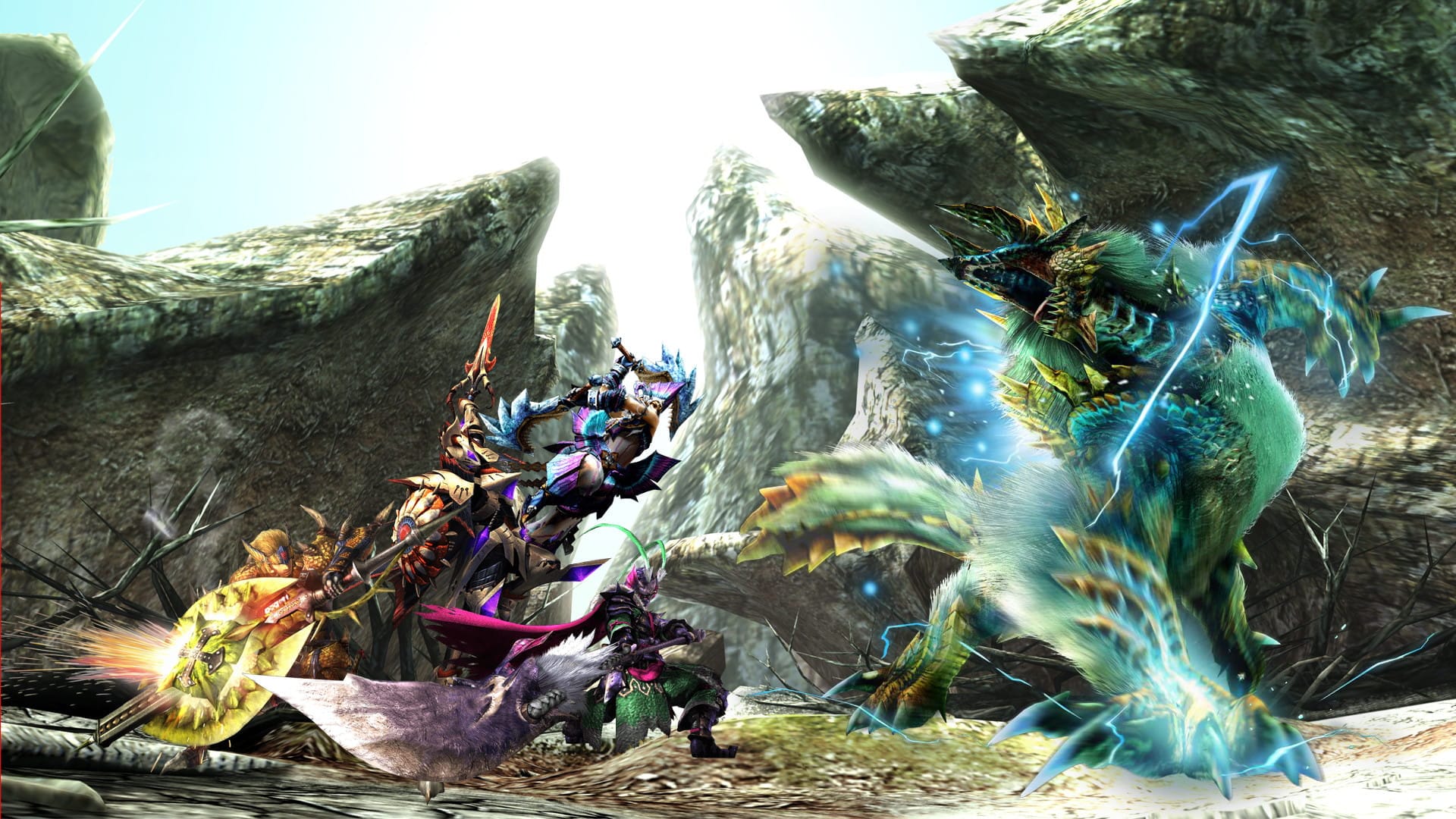

Add to that fan favorites like Luigi’s Mansion: Dark Moon, Bravely Default, and Monster Hunter 4 Ultimate, and the 3DS’s golden years were nothing short of spectacular. This was the era where the handheld stopped merely surviving—and began truly thriving.

Built-In Charm

Long before the big hitters defined the 3DS library, Nintendo had a little surprise waiting inside every unit: AR Games and Face Raiders. These weren’t blockbuster experiences, but they were showcases of what made the system feel futuristic.

With AR Games, a simple pack of cards transformed your desk or coffee table into a stage for archery challenges, target-shooting galleries, and 3D bosses that seemed to crawl right out of the real world. It was a clever reminder that the 3DS wasn’t just about screens—it was about blending reality and play.

Then there was Face Raiders, the bizarre but unforgettable shooter that plastered your own face (and anyone else’s you captured) onto floating enemies. Equal parts creepy and hilarious, it was Nintendo’s quirky humor at its finest, and a perfect icebreaker for showing off the system to friends.

Neither game was meant to be system-selling, but together they delivered a sense of built-in magic. Even before buying a cartridge, the 3DS could surprise, delight, and prove it was unlike any handheld that had come before.

If AR Games was the appetizer, StreetPass was the secret sauce that kept players carrying their 3DS everywhere they went. Using the system’s always-on wireless function, it quietly swapped data with other handhelds in close proximity. A simple walk through a mall, a commute on the train, or a day at a convention could transform into a treasure trove of digital encounters.

The heart of it all was the Mii Plaza, where avatars of people you crossed paths with would gather. Each new Mii meant progress in Puzzle Swap, where you pieced together vibrant panels featuring Nintendo artwork. Even better was StreetPass Quest (or Find Mii), a light RPG where your collected Miis became heroes battling monsters to rescue your royal avatar.

What seemed like a small novelty quickly became a cultural phenomenon. Suddenly, carrying your 3DS wasn’t just about games—it was about the thrill of connection. For many, it turned everyday errands into adventures, rewarding social interaction in a way no other handheld had attempted before. It wasn’t just innovative; it was quietly addictive.

Accessories and Oddities

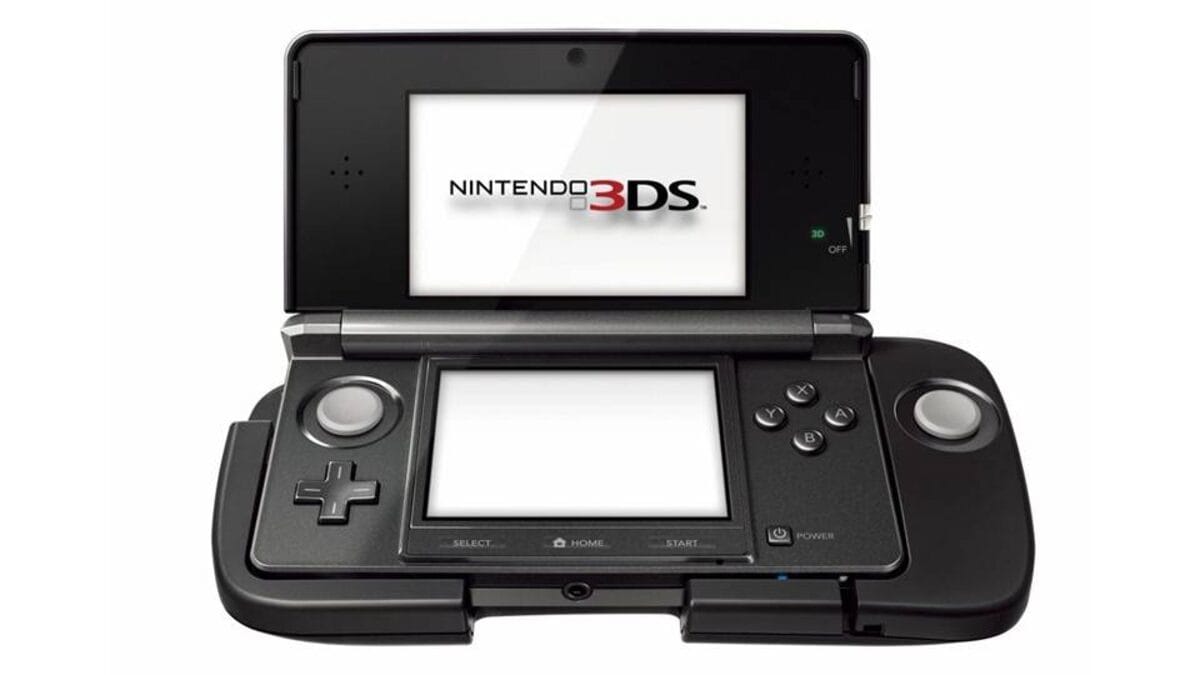

In 2011, Capcom’s Monster Hunter 3 Ultimate was gearing up to hit the 3DS, and fans had one big concern: how do you hunt massive creatures without a proper second stick? Nintendo’s answer came in the form of the Circle Pad Pro, an ungainly add-on that snapped around the 3DS like a life jacket.

This bulky peripheral added a second circle pad on the right side, along with extra shoulder buttons. It wasn’t pretty, and it made the handheld look almost comically oversized, but it worked. Games like Resident Evil: Revelations and Kid Icarus: Uprising suddenly had controls that felt closer to home-console quality.

While the Circle Pad Pro never became a mainstream must-have, it played an important role in the handheld’s history. It showed Nintendo was listening to developers’ needs, and in hindsight, it served as a stepping stone toward the New Nintendo 3DS, which eventually built that second stick directly into the hardware.

The 3DS era was nothing if not experimental, and Nintendo loved to sprinkle in an endless stream of optional extras to round out the experience. Take the charging cradle: a simple plastic dock that shipped with the original 3DS. It wasn’t strictly necessary—you could still plug the system in with a cable—but sliding the handheld into its little throne made topping up the battery feel oddly premium, almost like setting a gadget on display. Later models dropped it, turning the cradle into a quirky collector’s item.

Then came the Amiibo craze. While the New Nintendo 3DS line had built-in NFC support, older systems relied on a separate Amiibo reader: a small, puck-shaped peripheral that synced figures with your games. It wasn’t the sleekest solution, but it opened the door for Super Smash Bros., Animal Crossing, and countless other titles to tap into the toy-to-life gold rush.

Individually, these extras might have seemed minor. Together, they painted a picture of a company eager to keep experimenting, layering charm (and sometimes clutter) onto an already feature-packed handheld.

The Dark Side – Modding & Piracy

Where there’s a thriving platform, there’s a shadow economy waiting to bloom—and the 3DS was no exception. The horsemen arrived early in the form of R4 flashcards, carryovers from the DS era that let players run homebrew and, yes, pirated ROMs. Those little cartridges were cheap, pervasive, and bluntly effective—turning a handheld treasure trove into a borderline free-for-all.

Then came the twist: the 3DS wasn’t instantly conquered. Hackers had to be cleverer, and clever they were. A seemingly innocuous title—Cubic Ninja—contained a vulnerability that modders weaponized as an entry point into the system. Overnight, that cheap cartridge ballooned into one of the most expensive and sought-after games on the secondary market. Scarcity drove prices through the roof; suddenly a novelty party game became an illicit golden ticket.

Nintendo fought back with firmware updates and legal action, but the cat-and-mouse game persisted. Over time, the scene matured: what started as crude flashcarts and one-hit exploits evolved into sophisticated custom firmware and bootloaders. The result was a complicated legacy—one that damaged third-party sales, complicated region-locking and digital distribution strategies, and forced Nintendo to rethink security and service design for years to come.

Piracy didn’t define the 3DS, but it did shape its lifecycle—an unglamorous subplot that underlined just how valuable, and vulnerable, Nintendo’s handheld ecosystem had become.

As the 3DS matured, so did the ingenuity of its hacking community. What began with clunky flashcarts and game-specific exploits eventually crystallized into something far more powerful: Boot9strap. This custom firmware gave users near-total control of the system from boot-up, unlocking the hardware in ways Nintendo never intended. Suddenly, players could install games directly to the home menu, bypass region locks, and even breathe new life into aging hardware with fan-made tools.

And then came hShop, the community’s answer to a disappearing eShop. Styled like an underground storefront, it allowed users to download an entire library of 3DS titles, virtual console releases, and more with ease. No cartridges. No official servers. Just instant access. For many, it became the go-to solution after Nintendo began shuttering its digital services.

These breakthroughs cemented the 3DS as one of the most modded Nintendo consoles ever. To some, it was a playground for homebrew creativity and preservation. To others, it was piracy on a silver platter. Either way, it ensured the handheld’s relevance long after its official sunset—proof that when a community truly loves a system, they’ll find a way to keep it alive, rules or not.

3DS XL – Bigger is Better

By mid-2012, the 3DS had found its footing, and Nintendo wasted no time in broadening the hardware lineup. Enter the 3DS XL—or LL, as it was known in Japan—launched in July 2012 overseas and August in North America. Its pitch was simple but irresistible: bigger screens, better comfort, and longer play sessions.

The jump was dramatic. The XL’s displays were roughly 90% larger than the original 3DS, transforming portable play into something far more cinematic. Games like Mario Kart 7 and Super Mario 3D Land popped with new vibrancy, and the expanded field of view made the 3D effect easier on the eyes. Combined with improved battery life, it became the go-to model for marathon gamers who wanted fewer compromises on the road.

The XL wasn’t just a revision—it was the version that truly unlocked the 3DS’s appeal for many players. Released alongside New Super Mario Bros. 2, it helped solidify the handheld’s turnaround, proving that sometimes, size really does matter.

The 2DS – A Wedge of Cheese That Worked

In 2013, Nintendo unveiled what might be its strangest-looking handheld ever: the 2DS. Gone was the sleek clamshell design the DS family had made iconic. Instead, players got a flat, wedge-shaped slab that many joked looked like a slice of cheese. It couldn’t display games in 3D, the very feature the system was named after. On paper, it sounded like a step backward.

But in practice, it was a masterstroke. At just $129.99, the 2DS was the most affordable way into the 3DS library, and its hinge-free design made it practically indestructible—perfect for younger players. Parents loved the durability and price point, while kids got access to the same blockbuster titles as their 3DS-owning friends.

What seemed like a joke at first turned into a surprisingly successful branch of the family. The 2DS stripped away the gimmick but kept the games, and in the process carved out a niche that helped extend the handheld’s lifespan well into the next generation. Sometimes, less really was more.

The New Nintendo 3DS Line – A Subtle but Smart Upgrade

In 2015, Nintendo refreshed its handheld with the New Nintendo 3DS and New Nintendo 3DS XL, a mid-cycle upgrade that fixed many of the original’s shortcomings. On the outside, the smaller model introduced swappable faceplates, letting players personalize their system with everything from Mario patterns to retro pixel art. Inside, the hardware boasted improved processing power, a second analog input via the C-stick nub, and built-in amiibo support thanks to NFC functionality.

But the real selling point was comfort: super-stable 3D technology that tracked your eyes and eliminated the constant need to hold the console at a perfect angle. It was a game-changer for players who had given up on the original 3D effect.

Nintendo also experimented with exclusive titles, most notably Xenoblade Chronicles 3D, which showed off the power boost but also raised eyebrows—splitting the library between old and new hardware. Even so, the New 3DS line struck a balance between polish and accessibility, helping keep the system fresh in an era where smartphones were eating away at the handheld market.

The New 2DS XL – A Final Twist

In 2017, Nintendo pulled off one last surprise for the 3DS family with the New Nintendo 2DS XL. Unlike the original wedge-shaped 2DS, this revision embraced a sleek clamshell design that felt more in line with the 3DS XL, only slimmer and lighter. It dropped the stereoscopic 3D entirely, but that trade-off made sense—by then, most players weren’t using the feature, and cutting it allowed Nintendo to deliver a budget-friendly price without sacrificing performance.

Crucially, the New 2DS XL supported the entire 3DS library, including games enhanced for the “New” hardware. It came with the extra controls, NFC support, and faster load times of the New 3DS line, meaning you could play titles like Xenoblade Chronicles 3D and tap in amiibo without hassle.

It was a swan song for the family, releasing the same year as the Nintendo Switch. While the hybrid console stole the spotlight, the New 2DS XL gave the 3DS ecosystem a graceful final act—offering one last, affordable entry point into a handheld library that had by then become legendary.

Final Farewell

When the Nintendo Switch launched in 2017, Nintendo publicly insisted the Switch and the 3DS could coexist, each serving different markets. On paper, it made sense: one was a budget-friendly handheld with a massive library, the other a cutting-edge console bridging home and portable play.

But the reality was harsher. Developers flocked to the Switch, where the promise of bigger audiences and modern hardware was irresistible. The 3DS, meanwhile, started to feel dated overnight. Even its most charming exclusives couldn’t compete with the spectacle of Breath of the Wild in handheld form.

Nintendo kept supporting the 3DS with trickles of new content—remakes, spinoffs, and late-generation experiments—but the writing was on the wall. The Switch wasn’t just the next step forward. It was the replacement. The once-resilient 3DS suddenly looked like a relic of a bygone era.

In September 2020, Nintendo quietly announced the inevitable: the 3DS was officially discontinued. After nearly a decade of service, production lines went silent, and the handheld that had clawed its way back from disaster finally took its bow.

By the end, the numbers spoke volumes. Nearly 76 million units sold worldwide, and close to 400 million games finding homes in pockets, backpacks, and bedside tables. From shaky beginnings to a library bursting with beloved titles, the 3DS had transformed from a cautionary tale into a bona fide success story.

Its farewell wasn’t marked by fanfare or a lavish send-off. Instead, it left gracefully—its legacy carried on through the fond memories of millions who battled through StreetPass Quest, raised virtual pets in Nintendogs + Cats, or lost countless hours to Animal Crossing: New Leaf.

The 3DS didn’t just survive. It thrived, adapted, and ultimately proved that Nintendo’s gamble on glasses-free 3D, while flawed, could still deliver a console era worth celebrating. It was a handheld that overcame disaster—and in doing so, earned its place among Nintendo’s greatest achievements.

What began as a near-catastrophe—high prices, weak launch titles, and competition from the rising smartphone market—was salvaged by bold leadership, dramatic course corrections, and an ever-growing library of unforgettable games. The late Satoru Iwata’s willingness to take personal responsibility, including salary cuts and a sweeping price drop, sent a powerful message: Nintendo wasn’t ready to abandon its vision.

And that gamble paid off. With hits like Super Mario 3D Land, Pokémon X and Y, and Animal Crossing: New Leaf, the 3DS evolved from a gimmick-driven curiosity into a console with staying power. StreetPass gave it a social heartbeat, while constant hardware revisions—from the XL to the 2DS and beyond—ensured there was a model for everyone.

Nintendo’s Last True Handheld

The 3DS holds a bittersweet place in gaming history. It was Nintendo’s last dedicated handheld system, closing the book on a lineage that stretched from the Game Boy to the DS. With its clamshell design, quirky experiments, and a library packed with exclusives you couldn’t find anywhere else, it embodied the charm of portable-first gaming in a way no device has since.

When the Switch arrived, the landscape shifted. Nintendo no longer needed a separate handheld and home console—the hybrid had become both. In that moment, the 3DS transformed from a living platform into a symbol of an era that had quietly ended. It was the bridge between the cartridge-swapping childhoods of the Game Boy era and the seamless, all-in-one future of hybrid play.

For all its stumbles and triumphs, the 3DS remains a reminder of the days when handhelds weren’t just companions to consoles—they were the main stage. The end of its run marked not just the discontinuation of a product, but the closing of a chapter in Nintendo’s identity.