In the late 1970s and early ’80s, gaming was everywhere. Arcades were buzzing with chatter and the rhythmic clatter of quarters hitting metal. Kids huddled around Pac-Man cabinets, chasing high scores and sugary sodas in equal measure. Home consoles promised to bottle that magic, letting players bring the arcade home — a technological miracle wrapped in plastic and promise. Then, it all imploded. A tidal wave of low-quality games, corporate greed, and economic downturn reduced a booming industry to rubble almost overnight. Retail shelves overflowed with unsold cartridges; confidence was shattered.

Yet, from that wreckage, a new challenger emerged — bright, boxy, and defiantly simple. The Nintendo Entertainment System didn’t just launch a comeback; it rewired the DNA of gaming itself. But was it truly the savior of an entire industry—or just the right console at the right time?

The Crash Heard Around the World

By the dawn of the 1980s, video games weren’t just entertainment—they were a cultural obsession. Arcades were packed wall-to-wall with teenagers chasing pixelated glory, and the concept of “home gaming” was quickly becoming the next big frontier. Money was pouring in, headlines were calling it the future, and every corporation—from toy makers to cereal brands—wanted a slice of that ever-growing pie.

Then came the feeding frenzy. Companies that had never so much as touched a joystick suddenly decided they could make a console or publish a game. Mattel, Coleco, even Quaker Oats—yes, the oatmeal people—all threw their hats into the digital arena. To investors, it was a gold rush. To consumers, it was confusing chaos.

Every few months, a new console appeared on store shelves—each one claiming to be the next big thing. The Atari 2600, the Mattel Aquarius, the ColecoVision, the Videopac+ G7400, the Super Cassette Vision… the list went on and on. To the average family wandering through a department store, it was dizzying. Which console was worth the money? Which games would actually work on it?

Publishers didn’t seem to care. Their strategy was simple: flood the market and hope something stuck. Developers rushed games to shelves faster than they could test them, confident that the gaming craze would make anything sell. Retailers, desperate to cash in on the trend, stocked every system they could find—only to end up with aisles full of unsold hardware collecting dust.

If there was one thing companies learned in the early ’80s, it was that slapping a famous movie character on a game box guaranteed instant sales. Kids adored seeing their favorite heroes on the big screen — so naturally, they’d beg their parents to let them keep the adventure going at home. Publishers smelled easy money. Suddenly, nearly every blockbuster film had a rushed tie-in game to match.

The problem? Most of them were downright terrible. Developers were given only weeks — sometimes mere days — to churn out products that barely resembled the movies they were based on. Levels were incomplete, controls were sloppy, and graphics looked like someone had spilled pixel soup across the screen. But the packaging? Oh, the packaging was spectacular — colorful artwork and familiar faces masking what was often an unplayable mess.

Before online reviews, Reddit threads, or YouTube rants, there was only one way to find out if a game was worth your hard-earned cash — word of mouth. Playground gossip and lunchroom chatter were the early review aggregators, and when the collective verdict turned sour, it spread like wildfire.

The breaking point came with E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial for the Atari 2600. Made in just six weeks, it became the poster child for overconfidence and corporate short-sightedness. Millions of unsold copies were famously buried in the New Mexico desert — a literal graveyard for gaming’s greed.

As if the avalanche of bad games wasn’t enough, the early ’80s brought another cruel twist: an economic downturn that tightened wallets across America. Families were cutting costs, and luxuries like home consoles suddenly looked like frivolous expenses. Gas prices climbed, unemployment rose, and the disposable income that once fueled gaming’s meteoric rise started to dry up.

Players were fed up. Parents were angry that the expensive cartridges they bought barely worked. Retailers, burned by returns and unsold stock, started cutting back on game orders entirely. A single bad experience could turn a once-loyal fan into a lifelong skeptic. Without trustworthy quality control or consistent standards, the entire industry’s reputation took a hit.

Publishers and console makers, already struggling to offload bloated inventories, panicked. Instead of improving quality, they doubled down—pumping out cheaper, faster, sloppier games to keep revenue flowing. It was a race to the bottom, and consumers could see right through it. Shelves overflowed with bargain-bin titles, most of which weren’t worth their meager price tags.

By 1983, the enthusiasm that once fueled the gaming boom had curdled into skepticism. People weren’t just avoiding certain titles — they were walking away from gaming altogether. The market collapsed under its own weight, leaving mountains of unsold stock and shuttered companies in its wake. For a brief, bleak moment, it looked like gaming’s golden age had burned out entirely. Arcades dimmed, living rooms went quiet, and the idea of video games as a long-term industry seemed dead in the water.

Japan: Where the Lights Still Shone

While North America’s gaming market was imploding, Japan was living through an entirely different story. There, the industry wasn’t crashing — it was thriving. Arcades buzzed with life, packed with players chasing high scores on hits like Galaga, Xevious, and Donkey Kong. The energy was palpable, and rather than treating gaming as a passing fad, Japan’s developers viewed it as the next great entertainment frontier.

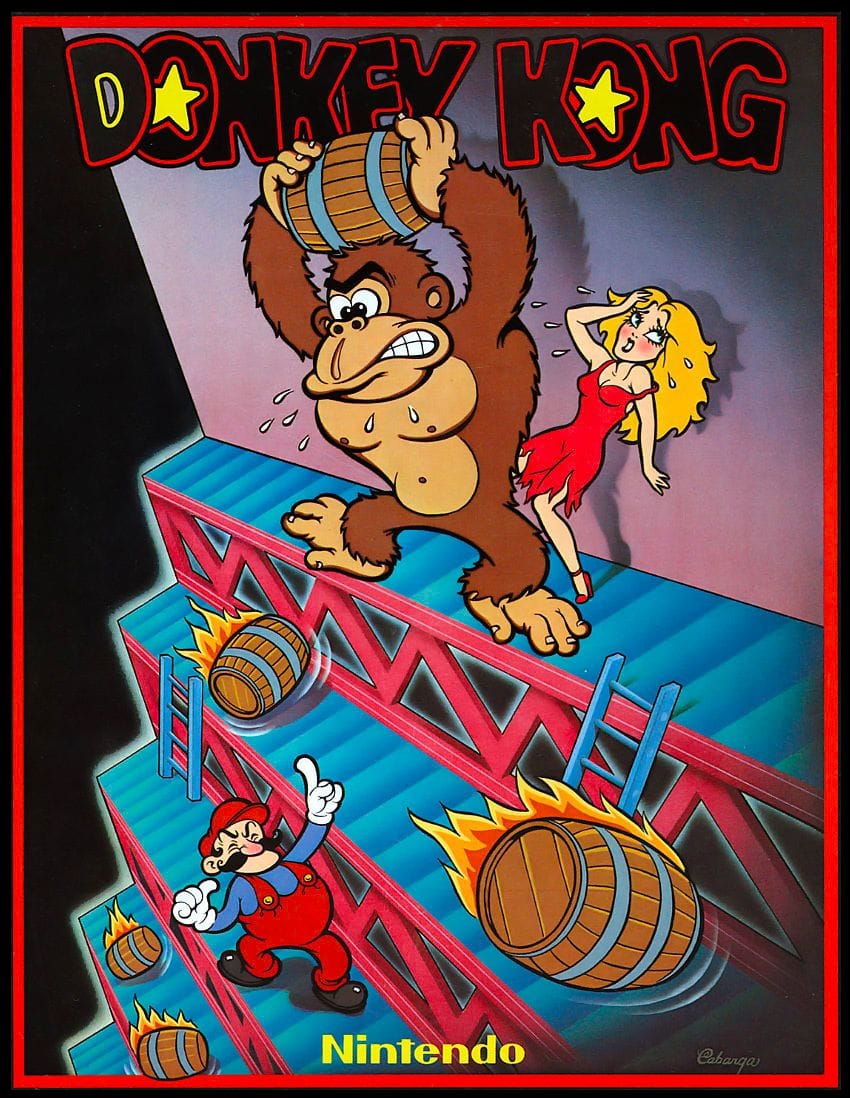

Nintendo, once a humble maker of hanafuda cards, was right in the thick of it. After finding success in arcades with Donkey Kong in 1981, the company sensed a shift coming. Japanese gamers weren’t satisfied with just dropping coins into machines anymore — they wanted that same experience at home. Competitors like Epoch were already capitalizing on this desire with the Cassette Vision, Japan’s first major home console hit.

Before Nintendo became the household name synonymous with gaming, it was a company constantly reinventing itself. What began as a hanafuda card manufacturer in the late 19th century had, by the 1970s, transformed into a toy and electronics innovator — experimenting with everything from light guns to arcade cabinets. The company’s knack for blending playfulness with technology was already apparent, but it was the dawn of the digital age that truly set Nintendo on its new trajectory.

This success lit a fire under Nintendo. If Donkey Kong could dominate arcades, why not bring that same thrill into homes? The company’s next move would take them from coin-operated machines to living room consoles — and in doing so, reshape the destiny of the entire gaming industry.

When Nintendo released Radar Scope in 1980, it was supposed to be their ticket to the booming arcade scene in America. On paper, it looked promising—a vibrant, fast-paced shooter inspired by hits like Galaxian and Space Invaders, complete with colorful visuals and a unique perspective. But the timing couldn’t have been worse. By the time the cabinets arrived on U.S. shores, the market had moved on, and players weren’t interested in another space blaster.

The game bombed. Thousands of unsold units sat gathering dust in warehouses, a potential financial disaster for Nintendo of America. President Minoru Arakawa, desperate to recoup the losses, called Japan for help. What followed would become one of gaming’s most pivotal pivots.

Hiroshi Yamauchi, Nintendo’s hard-nosed president, ordered the company’s young designers to reimagine Radar Scope’s hardware into something entirely new. A rookie developer named Shigeru Miyamoto took the challenge — and delivered Donkey Kong. What began as a salvage operation became an overnight sensation. The barrels rolled, Jumpman leapt, and arcades around the world roared back to life. Donkey Kong didn’t just save Nintendo; it proved the company had the creative spark to lead gaming’s next era.

The Birth of the Famicom

Fresh off the success of Donkey Kong, Nintendo was hungry to bring that same arcade magic into homes. In 1982, the company began work on a bold new project codenamed Gamecom — a console so ambitious it bordered on futuristic. The original concept was nothing short of audacious: a 16-bit powerhouse with a built-in keyboard, a floppy disk drive, and the potential to compete with home computers like the Commodore 64. It wasn’t just a console — it was meant to be a full-fledged family computer.

But one man wasn’t convinced. President Hiroshi Yamauchi believed that kind of complexity would scare off everyday consumers. Computers, in the early ’80s, still felt intimidating — sterile machines for offices, not living rooms. He wanted something approachable, toy-like, and affordable. So the grand vision was stripped back. Gone were the floppy drives and keyboards. What remained would evolve into a simpler, cartridge-based system — the Family Computer, or Famicom.

It was a decisive move. By abandoning the idea of power for accessibility, Nintendo chose not to compete with computers but to redefine what home entertainment could be. In hindsight, it wasn’t just a downgrade — it was genius restraint.

From the very beginning, Nintendo’s design philosophy for the Famicom was rooted in one simple idea: make it fun. Not intimidating. Not overly technical. Just instantly approachable — a machine that parents wouldn’t hesitate to buy and kids would be thrilled to play.

Masayuki Uemura, the engineer leading the project, envisioned something that felt more like a toy than a computer. He and his team drew inspiration from everyday playthings — bright colors, simple shapes, tactile buttons. The result was the now-iconic red-and-white console that looked friendly, not futuristic. Even the controllers were designed with delight in mind.

Every tiny detail was considered. A built-in microphone on the second controller? Why not — it might make games feel more interactive. Cables permanently attached to the system? Easier for families to manage.

While Nintendo was busy refining the Famicom’s design, inspiration struck from an unexpected source — the United States. Around this time, Coleco had just launched its ColecoVision, a console that stunned developers and consumers alike with its crisp visuals and smooth arcade-style performance. Compared to the aging Atari 2600, Coleco’s machine looked like a leap into the future.

Masayuki Uemura’s team took notice. One of the engineers, Takao Sawano, even bought a ColecoVision for his family — and what he saw changed everything. The Famicom couldn’t just match this kind of performance; it had to exceed it. To do that, Nintendo partnered with the chip manufacturer Ricoh, commissioning a custom picture processing unit (PPU) that could handle vibrant colors, dynamic backgrounds, and smooth sprite movement — all while keeping costs low.

Ricoh’s contribution was revolutionary. The PPU became the beating heart of the Famicom, enabling the kind of fast, fluid gameplay that arcade fans craved. Nintendo had found its secret weapon — cutting-edge technology wrapped in a toy-like shell. Takao Sawano borrowed the now-legendary D-pad design from Nintendo’s Game & Watch series, while Gunpei Yokoi suggested an eject lever purely because, in his words, “kids would enjoy the click.” It was the perfect blend of Japanese ingenuity and international influence, setting the stage for a console that would soon take the world by storm.

Launch of the Famicom

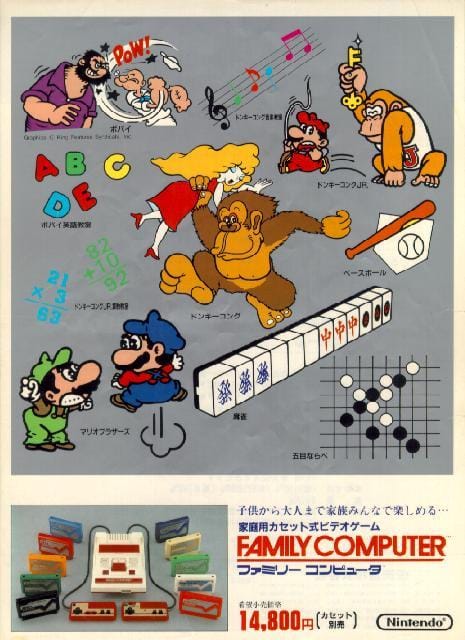

When the Famicom finally hit Japanese shelves in July 1983, excitement rippled through the air. Priced at 14,800 yen (roughly $150 at the time), Nintendo’s new console looked less like a piece of tech and more like a toy—a deliberate choice to make it approachable to parents still wary of the video game bust overseas. Its bright red-and-white design, hardwired controllers, and playful aesthetic screamed fun, not failure. Families lined up to see what this new “Family Computer” could do, and

The launch lineup was modest but powerful: Donkey Kong, Donkey Kong Jr., and Popeye—three titles that carried instant name recognition. Demand was explosive. Stores couldn’t keep up. For a brief moment, it seemed like Nintendo had struck gold. But the Famicom’s early success came with a cost. Hardware defects soon surfaced,

Then, disaster struck. Within months, reports flooded in of systems freezing mid-game or outright refusing to boot. Early units were plagued with hardware defects, forcing Nintendo into an embarrassing full recall before the holiday season. For a moment, it looked like Nintendo had stumbled at the starting line.

It could have been a disaster. Instead, it became a turning point. Nintendo recalled every defective unit, rebuilt the console’s motherboard, refined its internals, and relaunched the Famicom with improved internals. It was an expensive move — and a bold one — but it sent a message loud and clear: Nintendo cared about quality.

That decision restored public confidence. The Famicom was back on shelves and flying off them faster than Nintendo could produce more. By the end of 1984, the Famicom had sold over 2.4 million units, surpassing the Cassette Vision and cementing itself as Japan’s new home entertainment juggernaut.

But the Famicom didn’t just sell well; it restored faith. In a time when the global market seemed uncertain, Japan’s appetite for gaming was proof that the medium was far from dead. It was evolving, and Nintendo was leading the charge. The rough start was quickly forgotten, replaced by the unmistakable hum of 8-bit success.

Crossing the Pacific: Reinventing the Console

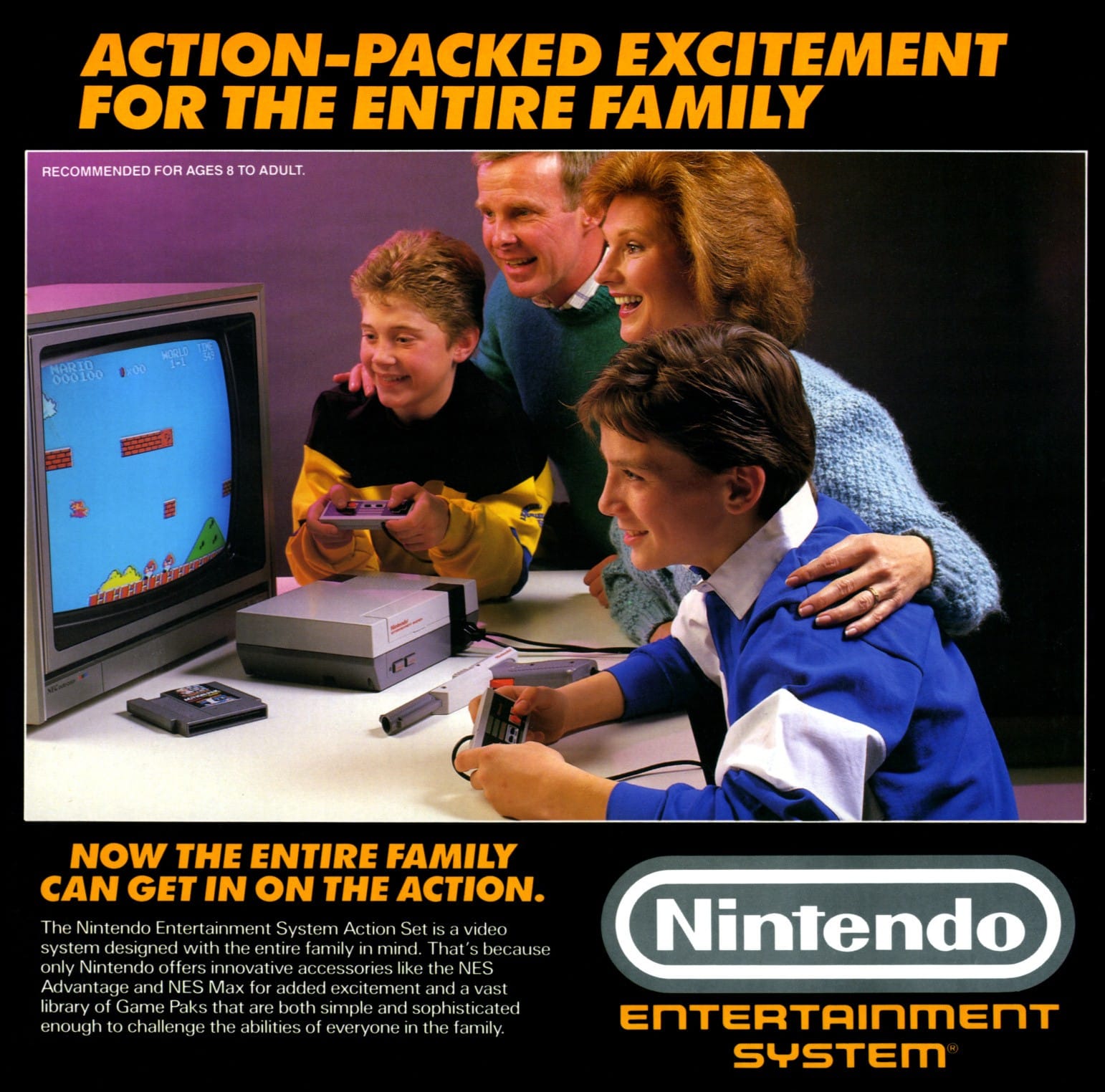

By 1985, Nintendo was ready to take its miracle machine overseas—but the American market was a minefield. The North American video game crash had left deep scars. Retailers were terrified of anything with the words “video game” on the box. Shelves still sagged under unsold cartridges, and consumers had been burned one too many times by cheap, broken promises.

Nintendo knew it couldn’t simply import the Famicom and hope for the best. It needed a reinvention—a total rebrand. So, the Nintendo Entertainment System was born, stripped of the word “computer” and wrapped in the aesthetic of consumer electronics rather than toys. Gone were the playful colors of the Famicom. In their place stood a sleek, gray box that looked more like a VCR than a game console.

To win over skeptical retailers, Nintendo bundled the NES with R.O.B. the Robot, a quirky peripheral positioned as an interactive toy rather than a gaming gimmick. It was a calculated illusion—a Trojan Horse to sneak video games back into American homes under the guise of innovation. And it worked. Once players picked up the controller and loaded Super Mario Bros., the charm of the 8-bit world did the rest.

R.O.B. — the Robotic Operating Buddy — was unlike anything the American toy market had ever seen. Standing at just under a foot tall, with swiveling arms and blinking eyes, it looked like something out of The Jetsons. Nintendo wasn’t selling just another console; it was selling the future — or at least, the illusion of it.

The strategy was pure genius. R.O.B. wasn’t just a gimmick; it was a marketing shield. By presenting the NES as an entertainment system with a robotic companion, Nintendo cleverly distanced itself from the tainted “video game” image of the early ’80s. Retailers who had sworn off cartridges and controllers suddenly saw potential in this high-tech toy.

In practice, R.O.B. only worked with two games — Gyromite and Stack-Up — both more fascinating in concept than in execution. But that hardly mattered. R.O.B. didn’t need to be good; he just needed to open doors. Once Nintendo had its foot in the retail aisle, the real magic began. Because hiding behind that friendly little robot was Super Mario Bros. — and he was about to remind the world why gaming was worth believing in again.

When Nintendo brought the NES to America, it wasn’t just selling games—it was selling trust. After years of shovelware and half-finished products flooding the market, consumers were wary. A flashy ad or a celebrity endorsement wouldn’t be enough to heal that wound. So Nintendo introduced something that would become iconic: the Nintendo Seal of Quality.

More than a logo, it was a promise. Every game bearing that gold stamp had passed Nintendo’s strict internal testing for performance, compatibility, and polish. Developers couldn’t just rush half-baked ideas to store shelves anymore; Nintendo enforced a notoriously rigid licensing system to maintain control over what players saw.

Critics at the time called it authoritarian. Gamers called it assurance. And for retailers? It was oxygen. The seal became shorthand for reliability—a small, circular emblem that told parents their purchase wouldn’t self-destruct after a weekend.

In an industry that had lost its integrity, Nintendo didn’t just rebuild confidence—it institutionalized it. The Seal of Quality became as much a part of the NES’s legacy as the gray cartridges themselves, transforming skepticism into faith, and faith into a gaming renaissance.

The NES Revolution

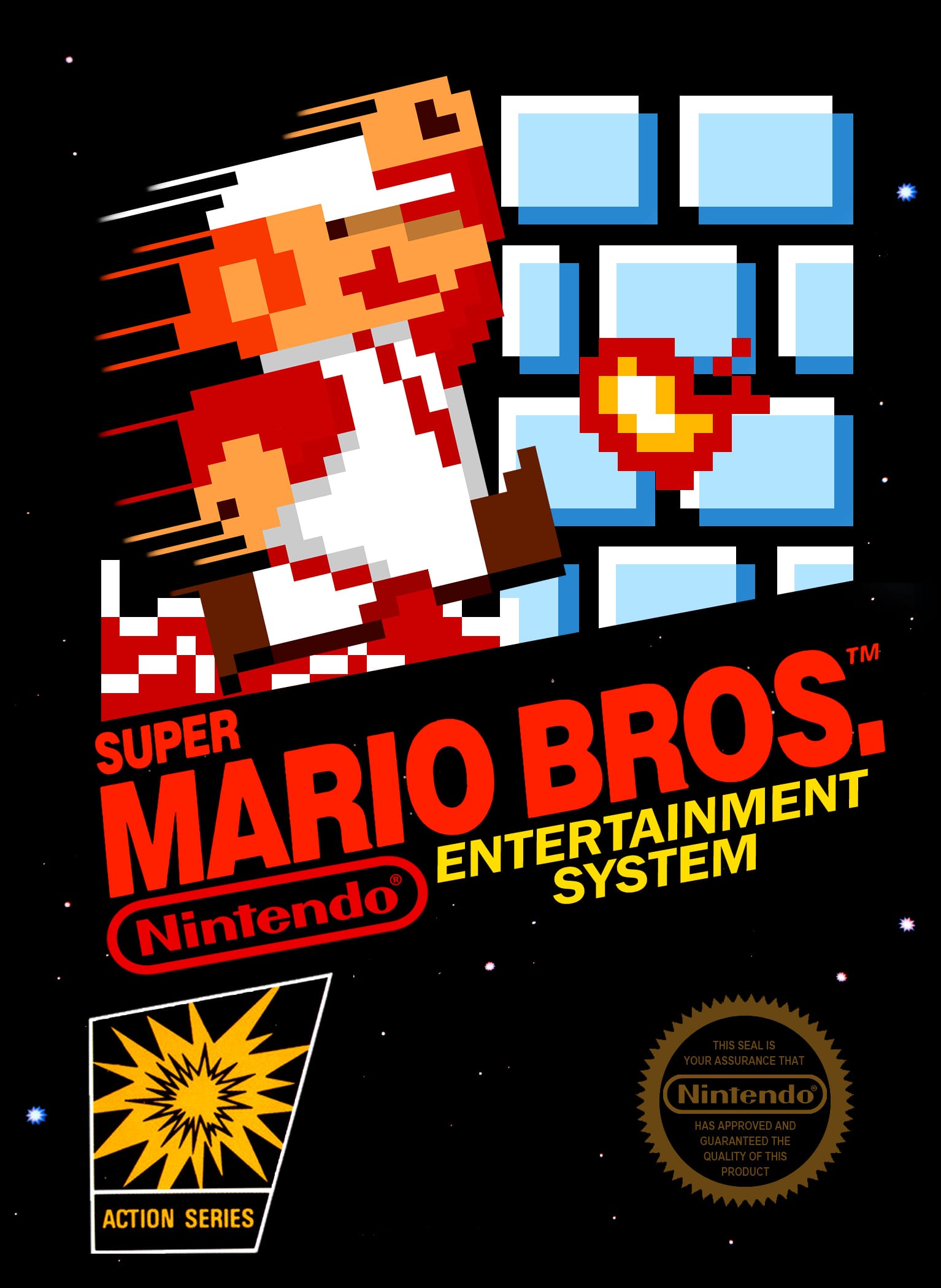

When Super Mario Bros. and Duck Hunt landed in American living rooms, they weren’t just games; they served as the perfect showcase for everything the NES could do. Super Mario Bros. redefined what a video game could be. Its tight controls, imaginative level design, and infectious soundtrack turned every player into an explorer. This wasn’t about chasing a high score — it was about adventure, about discovery.

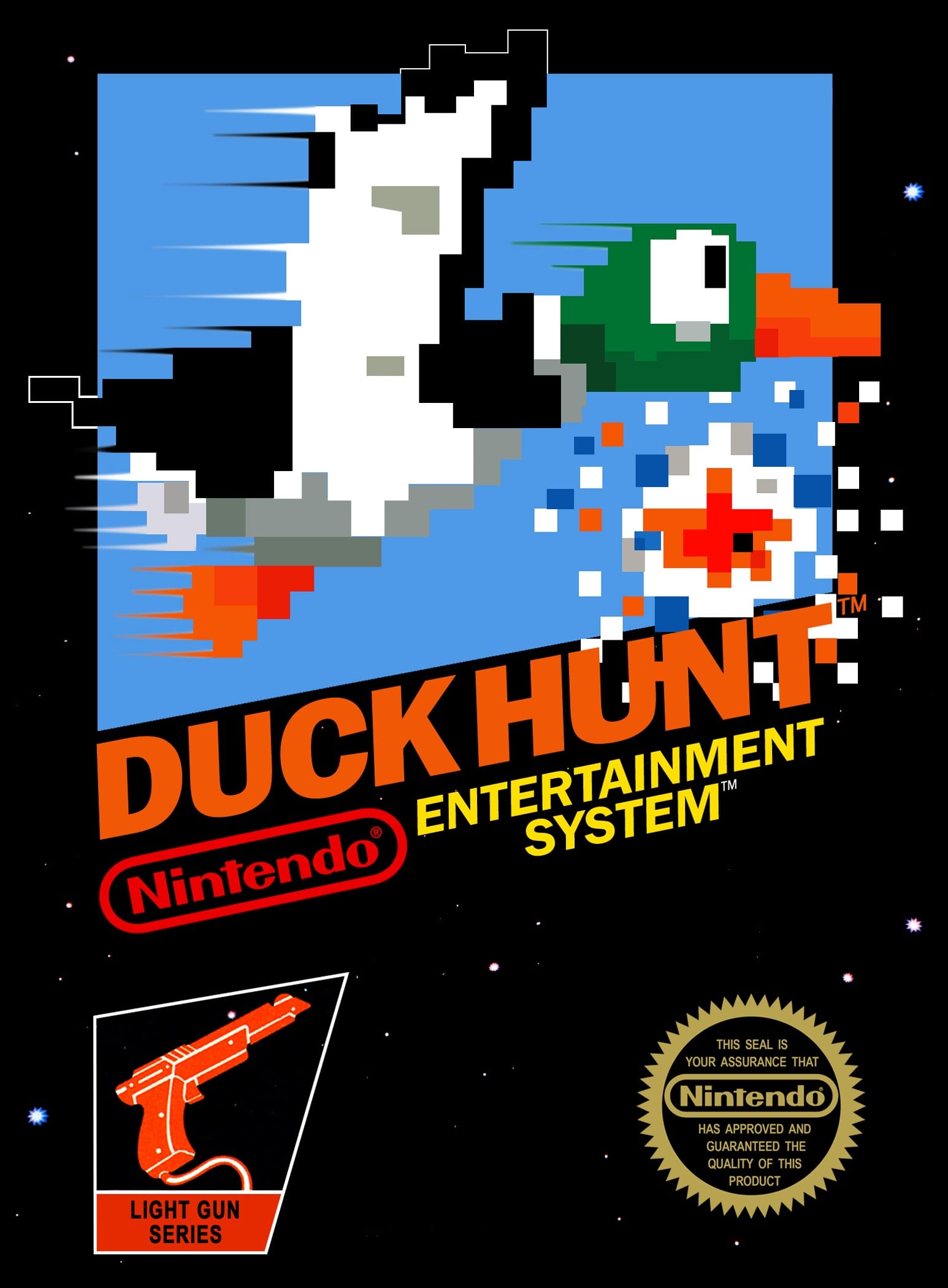

Then, once the controller was set down, Duck Hunt picked up the slack, turning the living room into a shooting gallery with the now-iconic NES Zapper. It was proof that video games could be more than pixels on a screen — they could be interactive, tactile experiences that pulled the whole family in.

Together, Mario and that mischievous dog did more than entertain. They restored faith in gaming as a medium. For a generation burned by cheap imitations, these two titles reminded everyone why they fell in love with games in the first place.

Once the NES found its footing, it became more than just a console — it became a launchpad for legends. Developers who’d once been constrained by the chaos of the pre-crash market now had structure, tools, and an audience hungry for quality. What followed was an explosion of ideas: Metroid’s eerie solitude, Mega Man’s electric battle themes, Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out!! colorful characters. For millions, these weren’t just games; they were formative memories.

While Nintendo’s first-party hits were the console’s heartbeat, its pulse quickened thanks to a new breed of collaborators — the third-party titans. Before the crash, licensing had been a free-for-all; anyone with a cartridge mold and a keyboard could publish a game. But under Nintendo’s watchful eye, third-party developers had to earn their place. And that discipline birthed excellence.

Companies like Capcom, Konami, and Square rose to prominence through the NES, each forging identities that would define gaming’s golden age. Mega Man, Castlevania, Contra, Final Fantasy — these weren’t just titles, they were statements of mastery. Each studio pushed the modest 8-bit hardware to its limit, proving that creativity thrived under constraint.

Nintendo’s strict policies sometimes bred frustration — cartridges were limited, approval was slow, and profits were split. But the trade-off was undeniable: a library with almost no filler and a level of consistency the market had never seen. The result? A new ecosystem of trusted developers whose names would become synonymous with quality, passion, and timeless play.

The Turning Tide

By the late ‘80s, the charm was still there — but the cracks were starting to show. What once felt limitless began to feel… confined. Developers had pushed the NES’s humble 8-bit hardware to astonishing heights, but pixels can only stretch so far. Gamers who’d grown up on Super Mario Bros. and Zelda were ready for bigger worlds, richer stories, and more cinematic flair.

The industry, as it turns out, was evolving faster than anyone anticipated. The Sega Master System boasted sharper visuals and smoother animation. Rival systems like NEC’s PC Engine teased the power of 16-bit computing. Even Nintendo knew the technology that had resurrected gaming was quietly aging out of its prime. The industry was no longer chasing Nintendo; it was catching up.

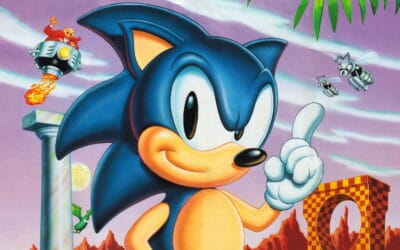

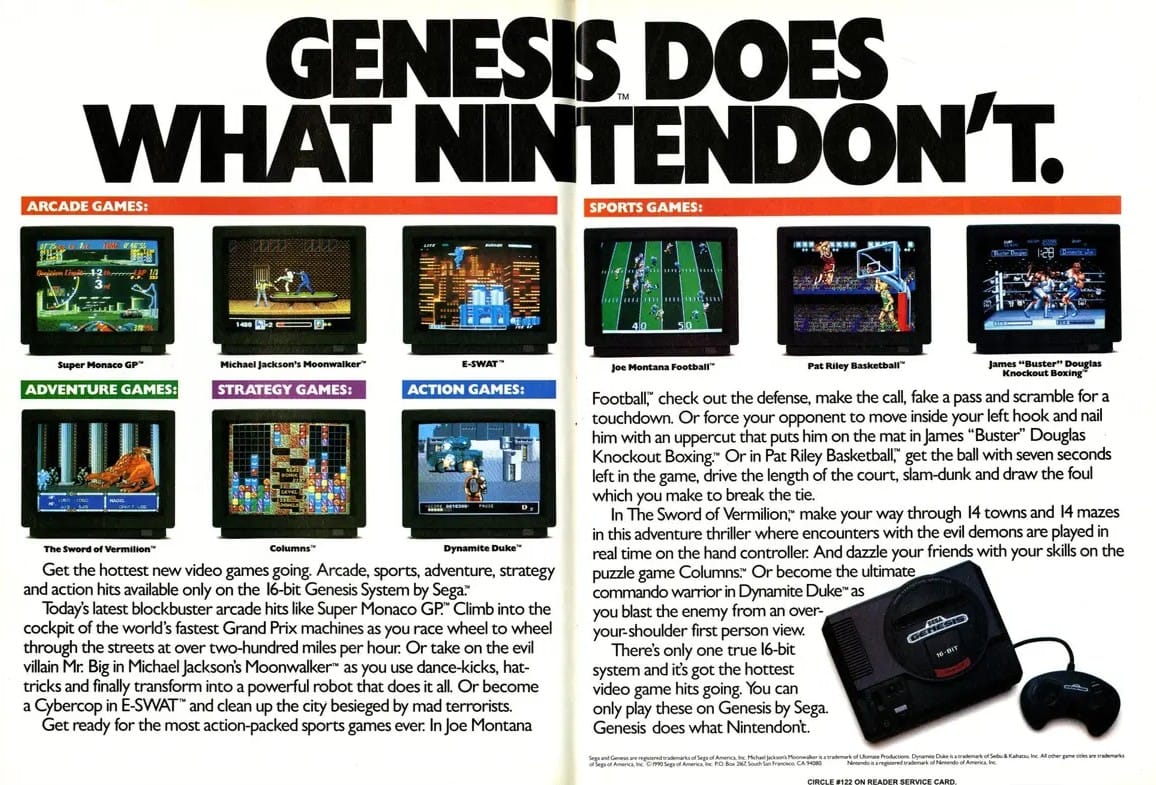

By 1989, the playground debates had turned into full-blown console warfare. Nintendo might have ruled the decade, but Sega had swagger — and wasn’t afraid to flaunt it. With the launch of the Sega Genesis, the company didn’t just enter the market; it kicked down the door with a smirk and a slogan that said it all: “Genesis does what Nintendon’t.”

It was brash. It was bold. And it worked. Sega’s marketing blitz painted the Genesis as the cooler, faster, more mature alternative to Nintendo’s family-friendly image. Where the NES offered charm, Sega countered with attitude — lightning-fast gameplay, edgy art direction, and a blue blur named Sonic who embodied everything Nintendo’s plucky plumber wasn’t.

As the 1990s dawned, the gaming world began to outgrow its training wheels. The children who’d once huddled around the NES were now teenagers craving something more daring, more sophisticated. The industry itself was maturing — evolving from a novelty into a mainstream medium with real artistic and commercial weight.

The stage was set for Nintendo’s next act. Blockbuster first-party makers were anxiously watching. Third‑party developers were flirting with richer hardware. Consumers wanted spectacle. Nintendo’s answer: not another incremental step, but a reimagined foundation for the future of console gaming—the Super Famicom (SNES), engineered to excel where the NES had limitations. A platform where audio, visuals, and gameplay harmony mattered more than clock speed.

Did the NES Really “Save” Gaming?

The early years of the NES were a cultural awakening. It reestablished consumer trust, set new quality standards, and laid the foundation for what a modern gaming ecosystem looks like. Take the controller, for instance. That simple rectangular pad with a D-pad and two face buttons became the prototype for all that followed. It replaced joysticks with precision and made comfort and intuitiveness part of the experience.

The licensing model was just as revolutionary. By curating what games could appear on the NES, Nintendo ensured consistency — and in doing so, created the concept of a trusted brand in gaming. Publishers had to earn their spot. Consumers learned to expect quality. It was capitalism, sure, but with craft baked in.

The company-imposed structure on chaos, turned developers into craftsmen, and transformed video games from a fleeting craze into a sustainable art form. Yet it also built walls, controlling what could be made and who could make it. Its success was both salvation and domination — a careful balance of creativity and corporate control.

It’s a question that lingers like an echo through gaming history: Did the NES truly save the gaming industry? While the romantic answer is yes, it didn’t single-handedly save it. When the video gaming industry crashed in North America, Japan & Europe weren’t affected. Personal computers such as the Commodore 64 and Apple Macintosh were also rising in popularity as an alternative way to play video games. But what the NES did do was give the medium something even more valuable: credibility. It proved that games could endure, evolve, and inspire — not just for a generation, but for all time.

The journey from the 1983 crash to the NES’s rise feels almost mythic — a phoenix story born from silicon and pixels. Nintendo didn’t just fill the vacuum left by Atari’s fall; it rewrote the rules of engagement. Without the NES, the crash might have lingered for years.

Conclusion

Four decades later, the NES still casts a long shadow. Its blocky sprites, chiptune melodies, and unmistakable gray cartridges are etched into gaming’s collective DNA. What began as a cautious experiment in a post-crash landscape evolved into the cultural cornerstone that inspired everything from the Game Boy to the Switch.

The NES proved that games could tell stories, that characters could become icons, and that hardware could inspire emotion. Every power-up, every castle rescue, every pixelated tune was a lesson in how joy could be engineered.

Today, you can still feel its pulse. Indie developers chase its simplicity. Modern consoles echo its design philosophy. Retro enthusiasts continue to hunt for those original cartridges like sacred relics. The NES wasn’t merely a machine; it was a movement that transformed play into passion and nostalgia into art. Even now, when we press Start, we’re still chasing that same spark the NES first ignited—a reminder that sometimes, the simplest pixels can leave the most permanent mark.