In 1973, a determined businessman named Eikichi Kawasaki acquired a bankrupt Osaka electronics outfit. No roadmap. No grand plan. Just raw ambition and a name that translated—almost cryptically—to “New Japanese Project”: Shin Nihon Kikaku.

What followed was a metamorphosis. From humble circuit boards to coin-operated dreams, SNK clawed its way into Japan’s fiercely competitive arcade scene. Before Street Fighter was a household name, before the Neo Geo became a luxury status symbol for hardcore gamers, SNK was quietly rewriting the rules. Vanguard, Micon Kit, Ozma Wars—titles that pulsed with pixelated energy and hinted at a bigger destiny.

This wasn’t just another scrappy upstart. This was the opening move in a story that would shape arcade culture for decades to come.

Early Blips and Breakthroughs

SNK’s first steps into gaming weren’t glamorous—but they were ambitious. The Micon Kit was essentially a video game test board, letting arcade operators swap out games quickly. It was practical more than revolutionary, but it laid the groundwork for SNK’s hardware-savvy reputation. Then came Ozma Wars in 1979—a vertical shooter in the mold of Space Invaders, but with a key difference: a fuel system and dynamic scrolling elements. It may not have redefined the genre, but it proved that SNK was watching the trends—and ready to evolve them.

SNK’s true breakthrough hit came with Vanguard, one of the first shooters to feature multi-directional scrolling and power-ups. It blended horizontal and vertical stages with a soundtrack that pulsed with futuristic energy. Distributed in the U.S. by Centuri, Vanguard became a cult favorite in arcades, particularly in the West. It was a bold, flashy signal that SNK could compete on a global scale—and win.

Vanguard’s success in America gave SNK a new perspective: if they wanted to succeed internationally, they needed boots on the ground. Rather than license out future titles and lose control over distribution, they established SNK Electronics Corporation in Sunnyvale, California—the heart of Silicon Valley arcade culture. This strategic move allowed SNK to skirt restrictive U.S. licensing deals and gave the company a direct pipeline into the American market. It was the first step toward global recognition—and it wouldn’t be the last.

Arcade to Console: Riding the NES Wave

In 1986, Ikari Warriors became SNK’s breakout blockbuster—a Commando-inspired run ‘n gun title with a twist: two-player co-op, rotary joystick controls, and a gritty military aesthetic that captivated players across Japan and the U.S. But its real legacy was sealed through its NES port. Though graphically toned down, the home version brought SNK into millions of living rooms and proved they could dominate on consoles just as much as they did in arcades.

Hot off Ikari’s success, SNK doubled down on explosive action. Titles like Guerrilla War and Victory Road offered similar chaos but expanded on the formula with more varied environments and weaponry. These games cemented SNK’s reputation for relentless action and stylish sprite work, earning ports to home computers and consoles across the globe. With each new title, SNK wasn’t just refining a genre—they were owning it.

By the late ’80s, SNK was at a crossroads. On one hand, they were producing hit arcade titles and successful console ports. On the other, they were growing increasingly interested in hardware development. Would they follow Capcom and Konami’s lead, staying software-focused and console-friendly? Or would they chart their own path—one that fused hardware and software into something wholly unique? That internal question would soon lead to a seismic shift—and the birth of the Neo Geo.

The Neo Geo Revolution Begins

Fresh off his work at Capcom—where he helped birth Street Fighter—Takashi Nishiyama joined SNK with an idea that defied the industry’s norms: what if arcade cabinets could work like game consoles, using interchangeable cartridges instead of fixed hardware? This modular design would slash costs for arcade owners and allow operators to refresh their cabinets with new games instantly. It was a radical rethink of the arcade business model—and SNK was all in.

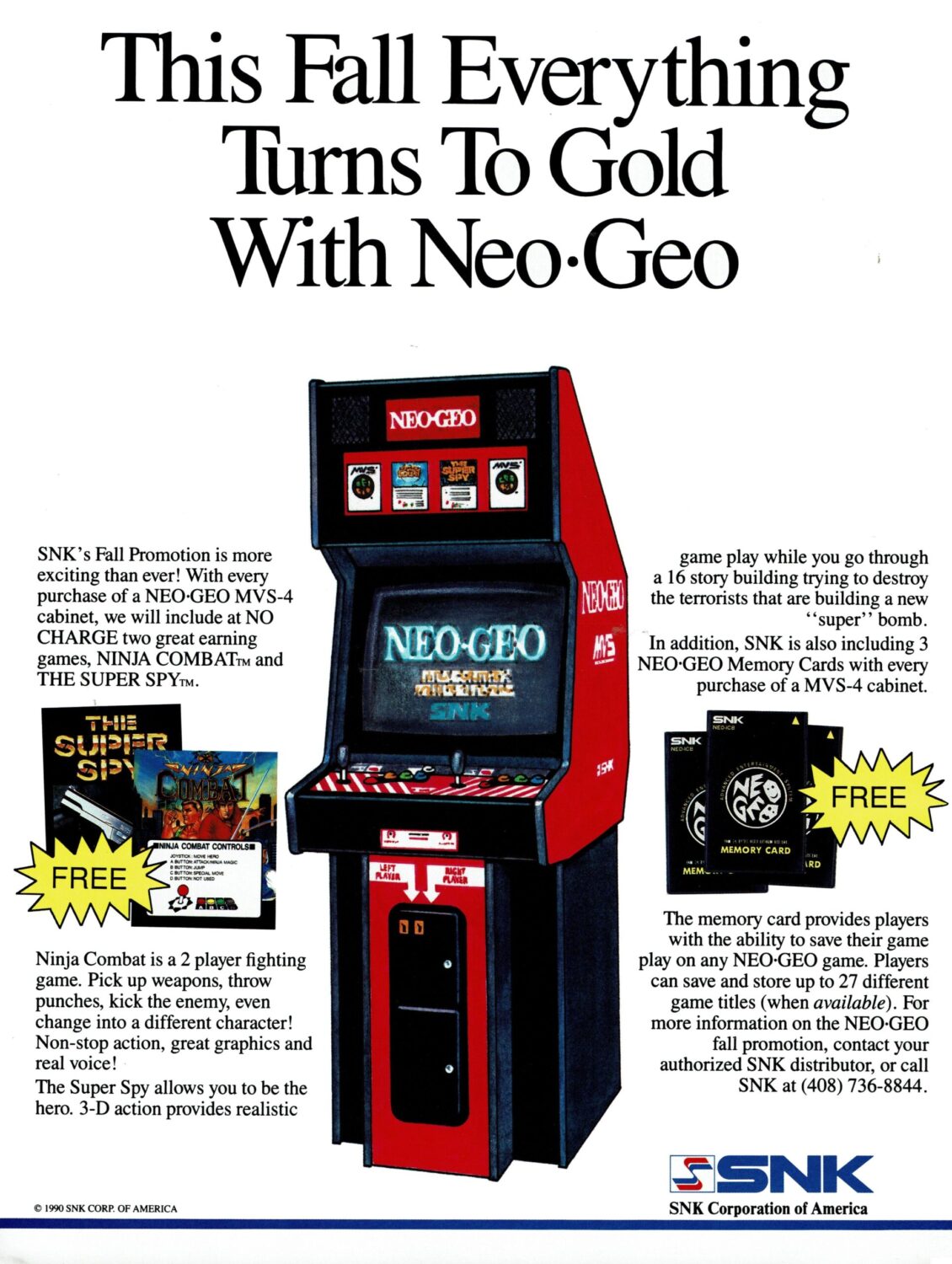

Launched in 1990, the Multi Video System (MVS) was the embodiment of Nishiyama’s vision. Arcade cabinets could now host up to six different games at once, with a simple switch interface for players. This not only saved money for operators but created a flexible platform for SNK to showcase a wide range of titles—from fighters to sports to side-scrollers. The MVS became a smash hit in arcades worldwide, particularly in North and South America, where its red cabinet became an icon in pizza parlors and mall arcades.

While the MVS revolutionized arcades, SNK took the unprecedented step of launching a home version—using the exact same hardware. The Advanced Entertainment System (AES) was pitched as a luxury console for serious gamers, featuring the same massive ROM cartridges as the MVS and arcade-accurate joysticks. But this wasn’t a toy—it was a high-end entertainment device, designed with sleek lines, a bold black finish, and performance that dwarfed anything on the market. At a time when Nintendo and Sega targeted kids, SNK aimed squarely at grown-ups who wanted the real arcade experience at home—no compromises.

While competitors leaned into toy-like aesthetics and bright plastic shells, SNK took a bold creative stance: the AES would look like high-end tech, not a child’s plaything. Inspired by the appearance of high-fidelity AV equipment, the design team focused on creating something sleek, serious, and aspirational. As SNK’s Toshiyuki Nakai later explained, they wanted the console to feel like a luxury product—something you’d proudly display in your living room alongside your stereo and VHS player.

“Our first design concept was: Let’s make something that looks cool! Many game consoles of that time had a rather childish design, similar to a toy. We wanted to create something that no one had seen before, a console with a simple and luxurious look. For this, a question quickly arose about the color of the console.

Nowadays, there is a lot of multimedia equipment with metallic colors, but at the time black was the most common color. Therefore, we chose black for the Neo Geo so that it wouldn’t look strange next to other audiovisual equipment in a living room. Black was also the cheapest color to use, and that was also a reason.”

- Toshiyuki Nakai, SNK

The Neo Geo AES launched with a price tag that dropped jaws: around $650 USD at launch, with individual game cartridges often retailing for over $200 each. But this wasn’t meant for mass market appeal—it was for enthusiasts who craved arcade-perfect ports and didn’t blink at premium pricing. The all-black shell, minimalist branding, and substantial weight gave the AES a serious presence. It wasn’t just another console—it was the Rolex of home gaming systems.

No dinky controllers here. The AES shipped with full-size arcade-style joysticks—complete with clicky microswitches and four face buttons. They weren’t just cosmetic choices; they were designed to mimic the feel of SNK’s arcade cabinets down to the millimeter. It was a clear signal: SNK wasn’t simulating the arcade experience—they were delivering it in full. For fans of fighters, shooters, and beat ’em ups, it was a dream come true.

Graphics, Sound, and Specs

When the Neo Geo launched in 1990, it wasn’t just powerful—it was in a completely different league. Boasting a 16-bit Motorola 68000 processor paired with a custom Z80 for audio, the system could push massive, richly animated sprites, smooth parallax scrolling, and arcade-quality audio with ease. While the Super Famicom and Mega Drive were still impressive for their time, the Neo Geo simply dwarfed them in performance. Games like Samurai Shodown and Fatal Fury were visual spectacles, packing more detail and character animation than anything seen on home consoles before.

One of the AES’s most forward-thinking features was its memory card slot—a first for home consoles. These cards could be used in both the MVS arcade machines and the AES console, letting players save their progress at the arcade and pick up right where they left off at home. In the early ’90s, this concept was revolutionary, anticipating cross-platform continuity decades before cloud saves and digital profiles. It was a glimpse into a connected gaming future, long before the infrastructure existed to fully realize it.

These weren’t just games—they were the exact same ROMs used in arcade cabinets. The high cost put the AES well out of reach for most casual gamers, but for the hardcore crowd, it was a badge of honor. Collectors, arcade junkies, and die-hard fighting game fans formed a small but passionate user base. For them, the AES wasn’t just a console—it was the ultimate statement piece.

Neo Geo’s Greatest Hits

Built to deliver uncompromising arcade experiences at home, the Neo Geo housed some of the most visually striking, mechanically deep, and culturally impactful games of its time. Here’s a deep dive into games that showed that 2D artistry could rival any polygonal flash, that arcade design still had room to grow, and that SNK was willing to push boundaries in both form and function.

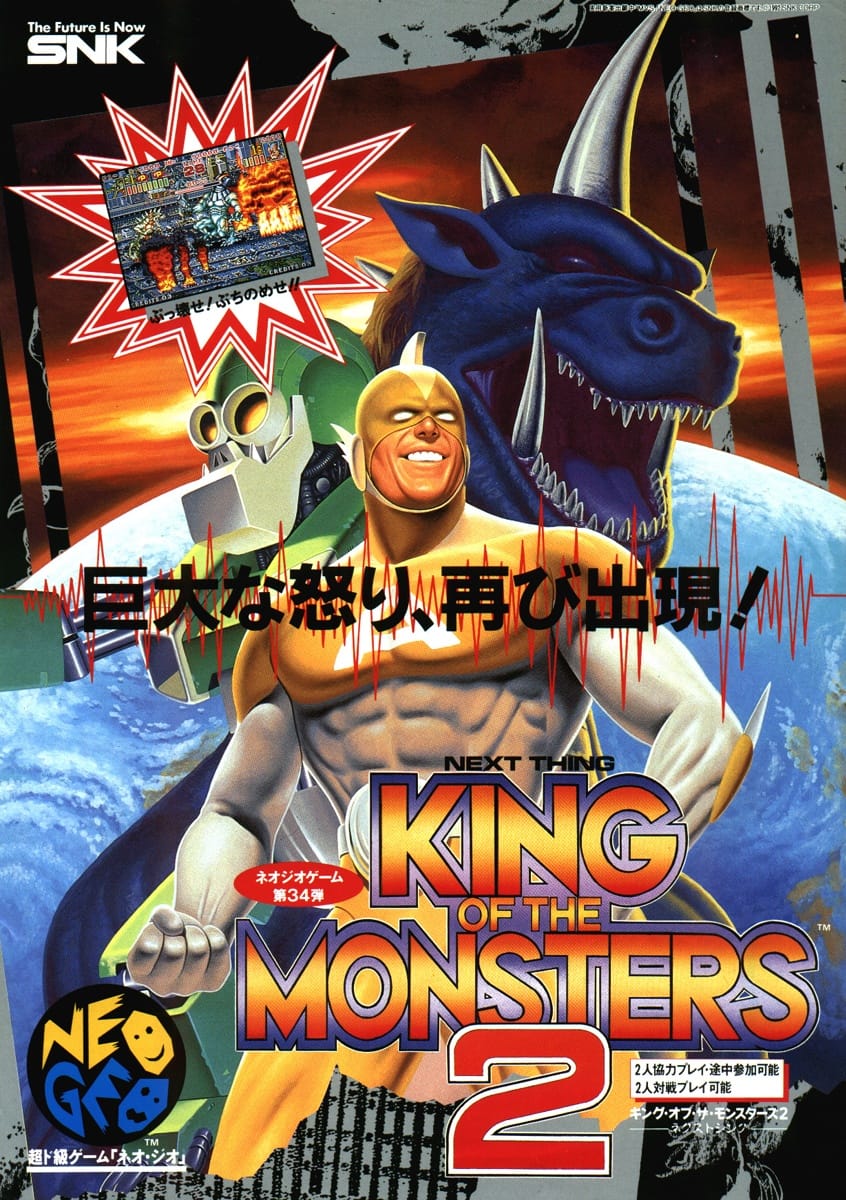

King of the Monsters 2 (1992)

Half wrestling game, half kaiju brawler, King of the Monsters 2 took its outrageous concept and ran wild. You stomp through cities as mutated beasts or alien horrors, slamming rivals into crumbling skyscrapers in what felt like SNK’s answer to Godzilla vs. Kong.

Giant Monsters, Giant Fun: While not the most technical game on the list, it was one of the most memorable thanks to its sheer spectacle and the giddy thrill of smashing entire stages to bits. It may have been simple, but it was endlessly entertaining in the arcade—and that was the point.

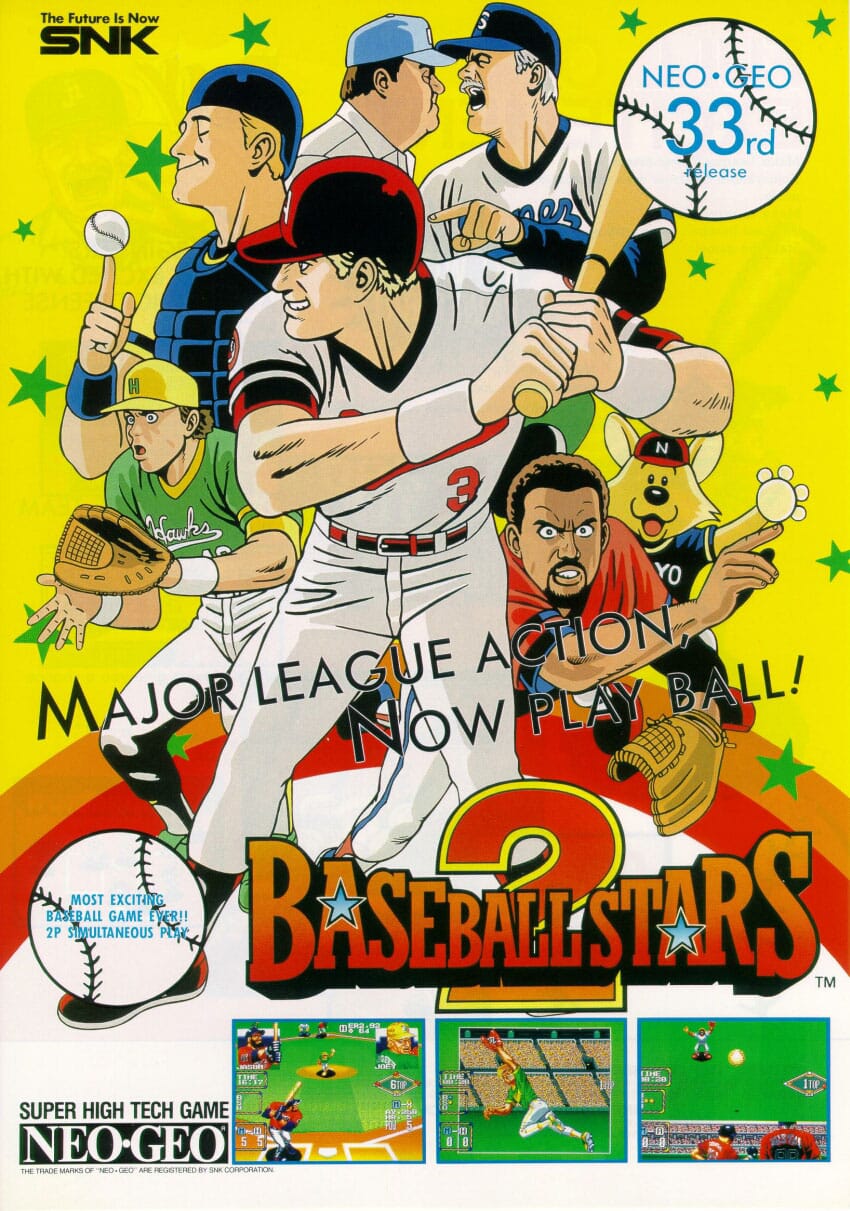

Baseball Stars 2 (1992)

Forget realism—Baseball Stars 2 turned the ballpark into an explosive, adrenaline-filled spectacle. With exaggerated player animations, dramatic slow-motion plays, and booming voice-overs, every inning felt like an action movie. But it wasn’t just flash. The gameplay was fast, intuitive, and surprisingly deep, blending arcade accessibility with strategic nuance.

Arcade Sports at Its Most Entertaining: SNK nailed the balance between immediacy and mastery, and no other arcade sports game captured that sense of momentum quite as well. It remains a beloved staple for multiplayer chaos.

Pulstar (1995)

Often compared to R-Type, Pulstar is a side-scrolling shooter with unforgiving difficulty and precise, methodical gameplay. But what set it apart was its presentation—every explosion, background element, and enemy was meticulously rendered in a pre-rendered style that gave it a 3D-like visual flair.

Beauty, Brutality, and Bosses You’ll Never Forget: The soundtrack was hauntingly atmospheric, adding a layer of tension that elevated the high-stakes combat. It's not the most accessible shooter, but for those up to the challenge, Pulstar delivers a thrilling, gorgeous journey through bullet hell.

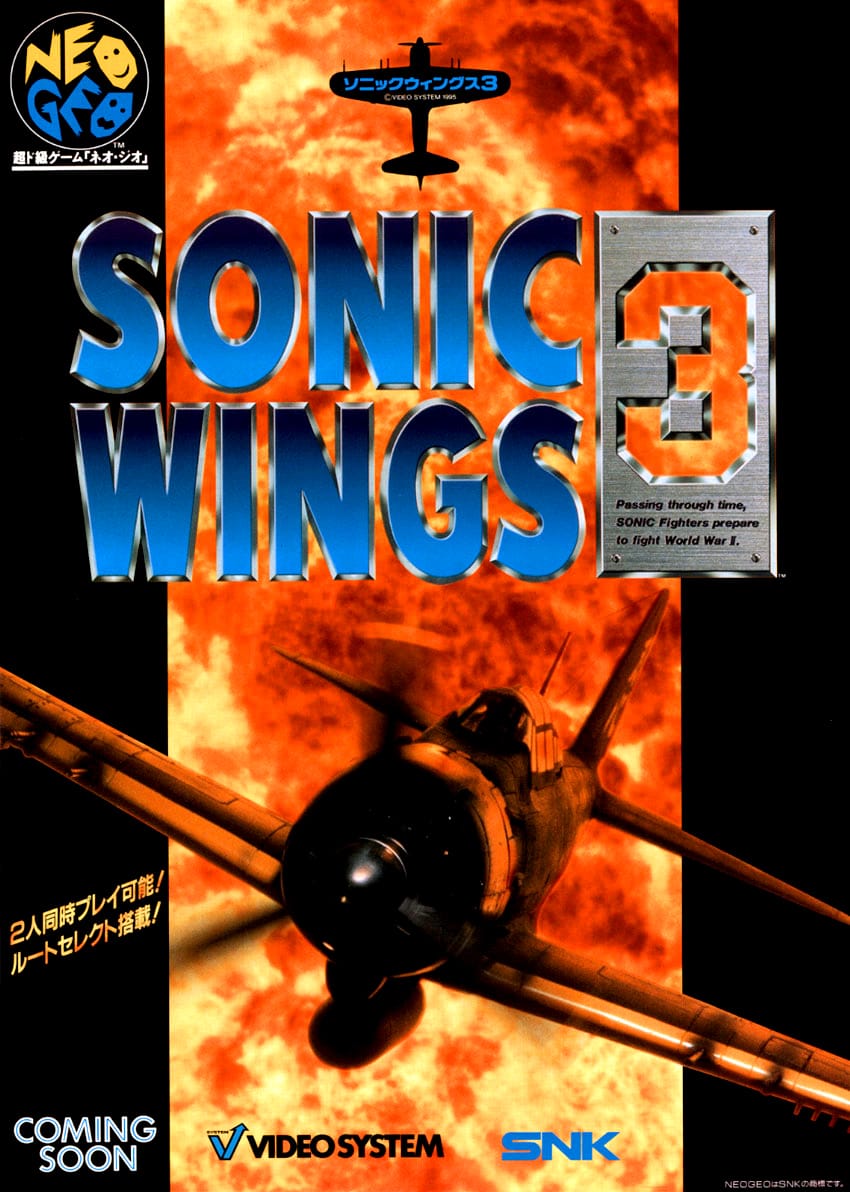

Sonic Wings/Aero Fighters 3 (1995)

As the final entry in the Aero Fighters trilogy, Aero Fighters 3 brought fast-paced vertical shooting to the Neo Geo with a generous helping of weird. While it featured the tight, explosive gameplay expected of a top-tier shmup—screen-filling bosses, power-up madness, and responsive controls—it was its eclectic tone that made it stand out. Where else could you pilot a dolphin in a jet fighter or see enemy pilots parachute out with a “NOOOOO!” scream?

Quirky Chaos in the Sky: With multiple characters, branching paths, and some of the most eccentric voice lines and endings in arcade history, Aero Fighters 3 embraced chaos with charm. It was a rare blend of classic arcade challenge and unapologetic personality, proving that Neo Geo shooters didn’t just have to be hardcore—they could be hilarious too.

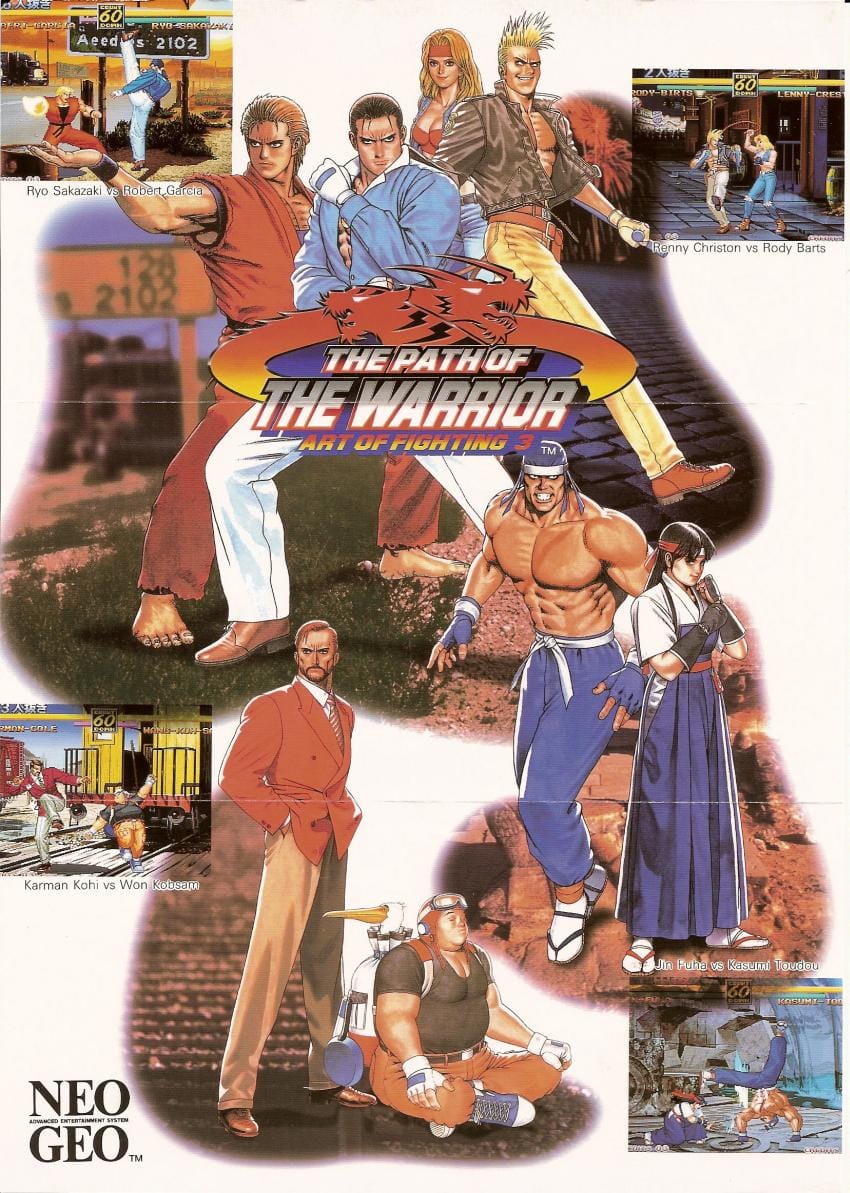

Art of Fighting 3 (1996)

Art of Fighting 3 went in a different direction from its predecessors, introducing rotoscoped animation that gave characters a uniquely fluid and lifelike feel. The game also featured a more grounded combat style, complete with intricate combos and responsive counters.

Rotoscoped, Reimagined, and Underrated: While it never hit the popularity heights of KOF, it was visually striking and technically ambitious. It felt like SNK experimenting with form and function, testing ideas that would influence fighters for years to come.

King of Fighters ’98 (1998)

More than just another sequel, King of Fighters ’98 is often considered the definitive entry in SNK’s flagship series—and for good reason. It refined nearly everything that came before it: tight controls, buttery animations, responsive inputs, and one of the most iconic rosters in fighting game history.

The Pinnacle of Team-Based Fighting: It stripped out narrative fluff to focus solely on pure competitive play, offering 3-on-3 battles that felt endlessly replayable. With 38 fighters drawn from across SNK's universe (Fatal Fury, Art of Fighting, Ikari Warriors, Psycho Soldier), it was a love letter to fans and a technical showcase of how to balance a massive cast.

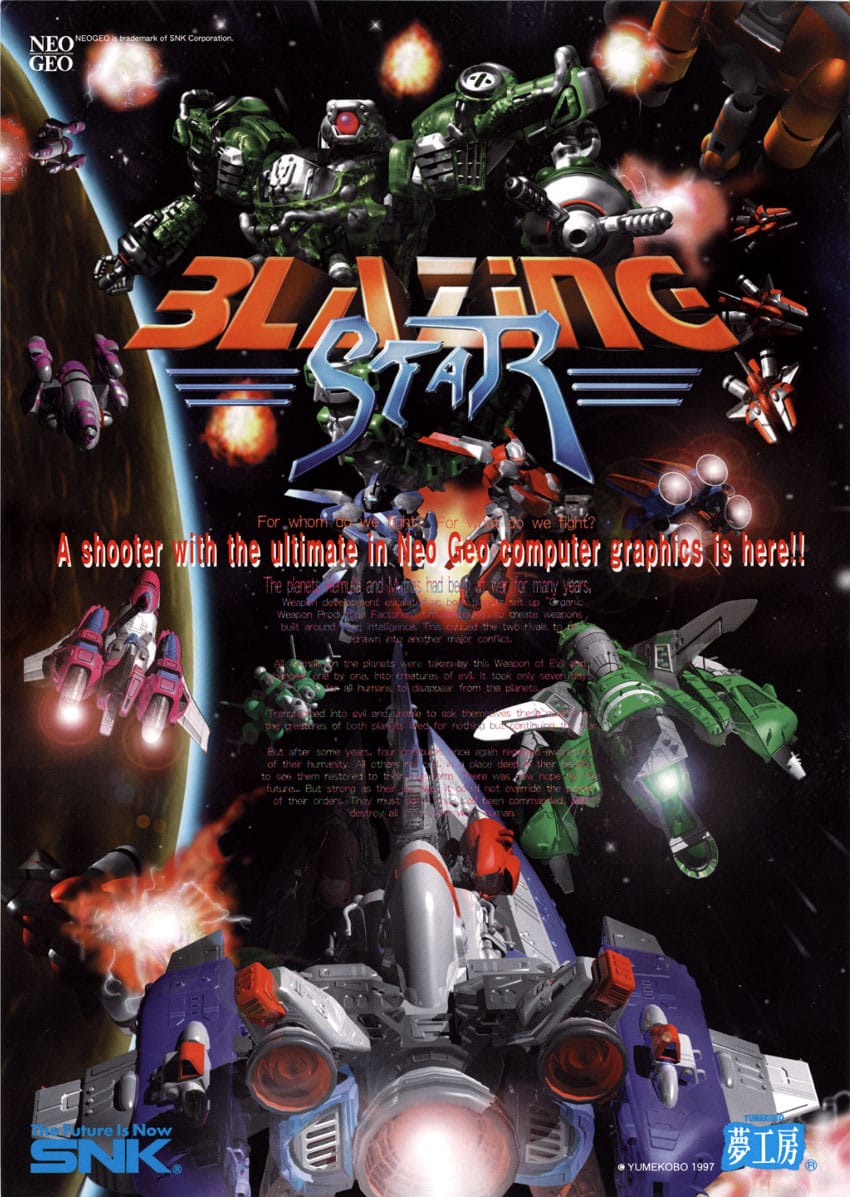

Blazing Star (1998)

Blazing Star didn’t just look good—it looked impossibly good. With vibrant, multi-layered backgrounds, sleek spacecraft designs, and animations that felt alive, it pushed the Neo Geo hardware to its absolute limits.

Eye Candy and Bullet Hell in Perfect Harmony: The game’s accessible mechanics, smart power-up system, and competitive scoring hooks made it addictive even for newcomers. It also leaned into SNK’s signature weirdness—engrish-laden voiceovers like “BONUS FOR DESTRUCTION” became cult-classic soundbites. It’s a masterpiece of style and shoot ’em up substance.

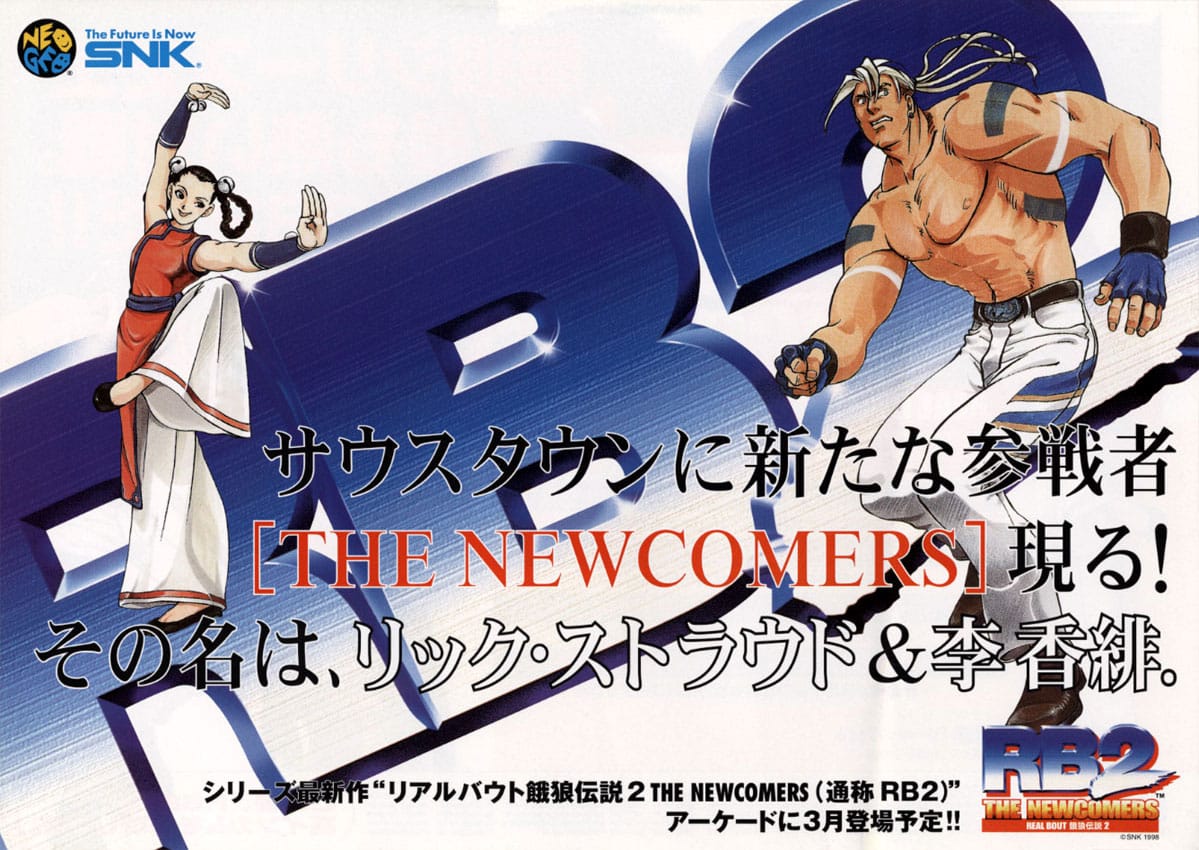

Real Bout Fatal Fury 2: The Newcomers (1998)

By the time Real Bout Fatal Fury 2 launched, SNK had mastered its fighting formula. This entry polished everything to a mirror shine—fluid controls, smooth animation, and a distinctive sidestep mechanic that added tactical depth.

The Stylish Side of Brutality: Real Bout Fatal Fury 2’s presentation was sharp and cinematic, and its pace was aggressive but rewarding. It brought in two new characters and improved balancing across the board, making it a go-to choice for Fatal Fury fans even today. This was SNK at its most confident, stylish, and mechanically sharp.

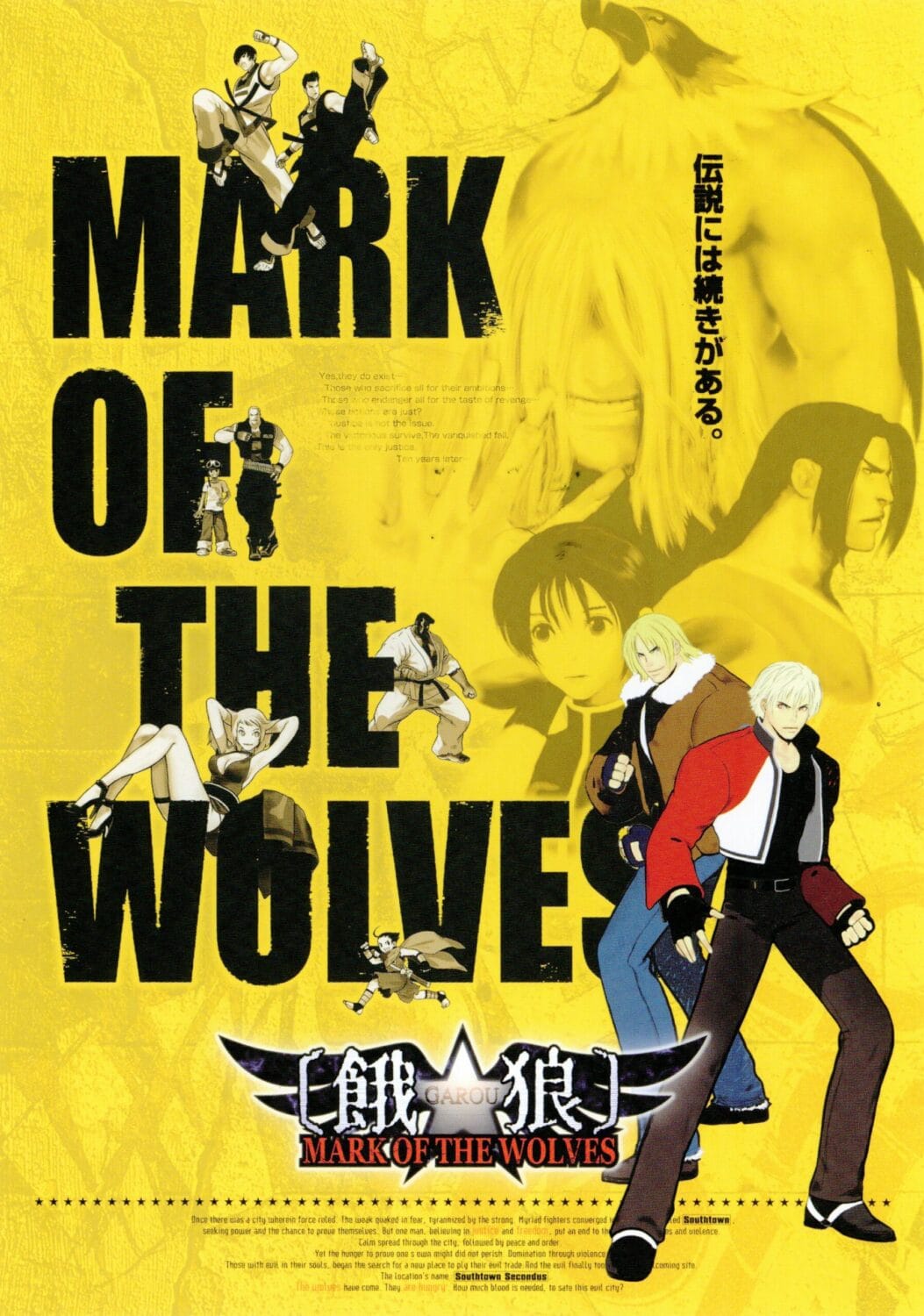

Garou: Mark of the Wolves (1999)

Garou isn’t just one of the best Neo Geo games—it’s one of the best 2D fighters ever made. Period. A spiritual successor to Fatal Fury, it introduced a new cast (led by Rock Howard, son of series villain Geese) and fresh mechanics like the T.O.P. system, which rewarded aggressive play.

SNK’s Finest Fighter: With unmatched sprite animation, elegant pacing, and a grounded yet expressive visual style, Garou felt like SNK’s answer to Street Fighter III: 3rd Strike—and in many ways, it surpassed it. It was both a farewell and a rebirth, showing that even in the waning days of the Neo Geo, SNK still had masterpieces left in the tank.

Metal Slug 3 (2000)

The Metal Slug series was already a genre-defining titan, but Metal Slug 3 is where it hit its apex. Everything was bigger—longer stages, more vehicles, more transformations, and even branching paths that added replay value. It combined absurd humor with jaw-dropping pixel art and tight, responsive gameplay.

Run ‘n Gun Royalty, Turned Up to 11: With branching paths, flying mech suits, and absurd boss fights, it pushes the Neo Geo hardware—and your reflexes—to the limit. It’s funny, brutal, and visually stunning. A true classic. No other run ‘n gun blended technical brilliance with cartoon absurdity quite like this. It's a masterclass in chaos.

SNK’s Struggle to Modernize

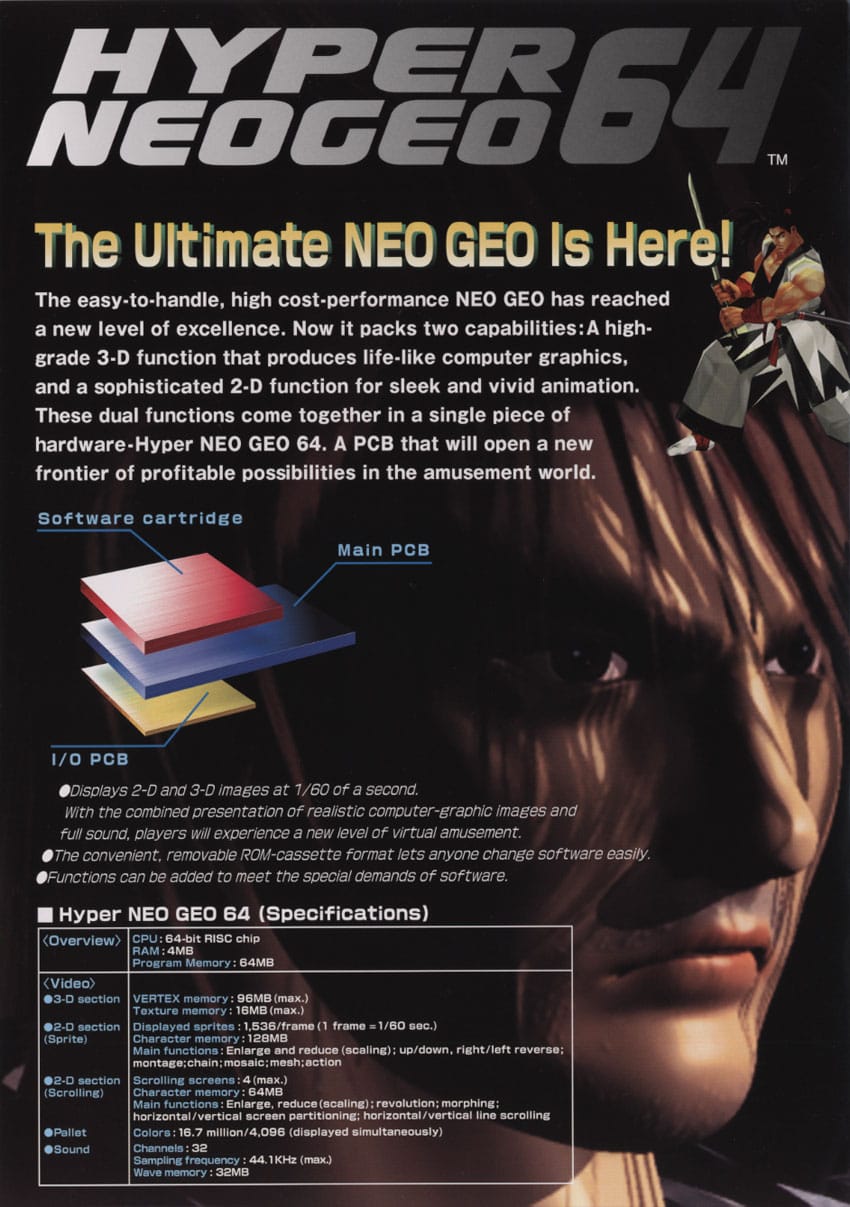

As the industry pivoted to 3D in the mid-’90s, SNK found itself in a difficult position. While the Neo Geo AES/MVS was still beloved for its 2D mastery, it was becoming increasingly out of step with the times. Sony’s PlayStation, Sega’s Model 2 boards, and Namco’s System 11 were stealing the spotlight with cutting-edge polygonal graphics. SNK knew it had to evolve or risk irrelevance. The solution? A brand-new hardware platform: the Hyper Neo Geo 64—designed to take SNK’s arcade legacy into the 3D age. On paper, it was a logical next step. In execution, it was anything but.

The Hyper Neo Geo 64 was first teased with great fanfare, and anticipation reached a peak when SNK revealed Samurai Shodown 64 as its flagship launch title. But at Japan’s 1997 AOU arcade show—where the world expected a live demo—all SNK had to show was a video tape with less than a minute of footage. Confidence in the hardware instantly wavered. When Samurai Shodown 64 finally did arrive in arcades, it looked and felt dated, lacking the polish and fluidity of its rivals. The absence of a true “wow” factor at launch set the tone for what was to come: missed opportunities and tepid reception.

The Hyper Neo Geo 64’s entire lifespan saw only seven games released—a shockingly low number for any arcade platform. Titles like Fatal Fury: Wild Ambition, Road’s Edge, and Samurai Shodown 64: Warrior’s Rage attempted to capture SNK’s 2D fighting magic in 3D, but struggled with clunky animations, awkward camera angles, and underwhelming visuals compared to what Sega and Namco were achieving. Arcade operators were unimpressed, and fans stuck with the tried-and-true Neo Geo MVS. The platform lacked a killer app, suffered from poor third-party support, and quickly became obsolete. By the turn of the millennium, the Hyper Neo Geo 64 was quietly discontinued—an ambitious misfire that marked the beginning of SNK’s financial troubles.

The Neo Geo Pocket Era

After the Hyper Neo Geo 64’s underwhelming performance, SNK pivoted to the booming handheld market. In 1998, they launched the Neo Geo Pocket in Japan—a monochrome handheld with surprisingly deep gameplay and excellent battery life. A year later, they followed it up with the Neo Geo Pocket Color (NGPC), a full-color upgrade that directly targeted Nintendo’s Game Boy Color. Unlike its predecessor, the NGPC saw a global release, including North America and Europe. With refined hardware and a compact, ergonomic design, SNK was no longer just chasing the market—they were ready to compete.

The NGPC was a technical and creative success. It featured a high-contrast color screen, a brilliant microswitched analog-style thumbstick (still praised to this day), and a surprisingly strong lineup of games. From the excellent SNK vs. Capcom: Match of the Millennium to deep card battlers like Card Fighters Clash and even solid adaptations of Metal Slug, it punched far above its weight. But timing is everything. Nintendo’s Game Boy had a stranglehold on the market, and the surprise launch of the Game Boy Advance in 2001 sealed the NGPC’s fate. Despite glowing reviews, it was swept aside by a handheld juggernaut.

While the Neo Geo Pocket Color only managed to claim a tiny sliver of the market—around 2% in North America—it earned a passionate following. Its games were polished, its build quality top-tier, and its design choices smart and forward-thinking. It didn’t try to replicate console experiences; it built bespoke handheld ones. For many, it was a hidden gem in an era of handheld sameness. Today, the NGPC is fondly remembered by collectors and retro enthusiasts alike—not just as SNK’s last major hardware push, but as one of the most charming and well-crafted handhelds ever made.

The Collapse and the Comeback

By the early 2000s, years of mounting losses and failed hardware ventures finally caught up to SNK. Despite having a loyal arcade fanbase and the cult status of the Neo Geo, the company couldn’t compete with the marketing power and technological momentum of Sony, Sega, and Nintendo. In 2001, SNK filed for bankruptcy. Its intellectual properties were sold off, and much of its staff dispersed. The Neo Geo Pocket Color was discontinued, the AES/MVS faded into nostalgia, and the future of iconic franchises like Fatal Fury, Samurai Shodown, and King of Fighters hung in the balance. SNK’s reign as an arcade powerhouse seemed to be over.

But SNK didn’t stay dead for long. Former founder Eikichi Kawasaki returned and quickly formed Playmore Corporation, a new company that began acquiring SNK’s old assets—including the beloved IP catalog. By 2003, the newly renamed SNK Playmore was officially in control of the brand again. The studio shifted its focus to ports, collections, and licensing deals, while slowly building up enough momentum to release new games. While much of the magic of old SNK was gone, the fighting spirit remained. Over time, SNK Playmore rebuilt the studio’s credibility and tapped into the nostalgia of fans worldwide.

Even during SNK’s darkest years, one franchise never stopped throwing punches: The King of Fighters. New entries kept coming, even on modest budgets, and the series became a standard-bearer for SNK’s survival. With the release of KOF XIII and XIV, the company finally began to modernize its output—moving into high-definition visuals and re-entering the competitive fighting game scene. By the time The King of Fighters XV dropped in 2022, SNK was once again back on the global stage. Through acquisitions, re-releases, and carefully crafted revivals, SNK’s classic spirit—built in the arcades of the ’90s—continues to inspire a new generation of gamers.

Why SNK Still Matters

Though SNK’s market share never rivaled Sega or Nintendo, its influence runs deep—especially among collectors and retro gaming aficionados. The Neo Geo AES has become a status symbol in gaming culture, with its massive cartridges, premium design, and arcade-perfect fidelity. Original hardware and games often fetch thousands on the resale market, not just because they’re rare, but because they represent a lost era of uncompromised game design. Even the distinctive red MVS cabinets remain staples in arcades, game bars, and private collections across the world. For many, SNK didn’t just make games—it made artifacts.

SNK dared to treat video games as more than toys. Long before Sony brought “adult” aesthetics to the PlayStation, SNK built a console that was black, sleek, and high-end. Its joysticks were arcade-quality out of the box. Its memory card system allowed for cross-platform play—in the early ’90s. The company focused on delivering experiences that were faithful to their original form, at a time when most arcade ports were watered down. SNK wasn’t interested in mass appeal; it was obsessed with fidelity, form, and function. Today, with retro-styled consoles, premium collectors’ editions, and digital re-releases in full swing, it’s clear SNK was simply ahead of the curve.

Even as arcades faded from cultural relevance, SNK’s legacy endured—because their games were built for arcades. Fast, responsive, challenging, and endlessly replayable, their design DNA continues to influence modern game design. Fighters like KOF, brawlers like Sengoku, and run ‘n guns like Metal Slug still thrive through compilations, tournaments, and fan-made revivals. The SNK spirit is one of unfiltered play: big sprites, bold ideas, and brutal difficulty wrapped in impeccable style. In an age of microtransactions and 100-hour RPGs, SNK’s approach—tight gameplay, pick-up-and-play pacing, and visual flair—feels refreshingly timeless.

SNK may no longer dominate the industry, but it still defines a part of it. Its work echoes in every indie fighting game, every retro collection, and every click of a micro-switched joystick. For those who grew up in arcades—or simply admire what they stood for—SNK remains a name worth remembering.

Final Thoughts

What began as Eikichi Kawasaki’s gamble with a bankrupt electronics company turned into one of Japan’s most beloved gaming brands. From modest shooters like Ozma Wars to genre-defining giants like King of Fighters and Fatal Fury, SNK’s catalog is as rich as its history. Even its missteps—like the Hyper Neo Geo 64—tell a story of ambition, risk-taking, and a refusal to simply follow trends. SNK never had the biggest slice of the pie, but what it offered was always flavorful, bold, and memorable.

In a world where home console ports often meant cutting corners, SNK stood firm. The Neo Geo was arcade hardware first and foremost, and the home experience wasn’t a downgrade—it was the same. That purity of vision, that unwillingness to dilute its games, has earned SNK a place in the hearts of connoisseurs and historians alike. It wasn’t about chasing the biggest audience—it was about creating the best experience, every single time.

SNK’s story is one of resilience, passion, and artistic integrity. It may not have ruled the console wars, but it carved out something arguably more important: a legacy. One that still burns brightly, joystick in hand, pixel by pixel.