In the twilight of the 1980s, Nintendo wasn’t just winning—it was unchallenged. The NES had transcended toy status and become a cultural monolith, turning “playing Nintendo” into a verb in households from Tokyo to Toledo. By 1989, Nintendo commanded an astonishing 95% of the American home console market. Not Sony. Not Sega. Not even a whisper of competition. It was empire-building in cartridge form.

But beneath the triumphant press releases and warehouse shortages, change was coming. Quietly. Inevitably. The 8-bit age is approaching its end. Rivals were sharpening blades. NEC had launched its high-tech PC Engine in Japan. Sega was readying its blast-processed Genesis with bold ads and faster chips. And developers—once compliant—were beginning to chafe under Nintendo’s iron-fisted licensing rules.

Nintendo stood on a cliff. The world was watching. Would the leader of video games cling to its honor, or rise again with a machine that would redefine what a console could be?

This is the story of the Super Nintendo Entertainment System. The console that didn’t just follow the NES—it eclipsed it.

From Famicom to Phenomenon

Before the Super Nintendo dazzled the world with Mode 7 and sweeping audio scores, Nintendo had already revolutionized gaming once. The Famicom (Family Computer), launched in Japan in 1983, was a bold gamble that defied skeptics and redefined home entertainment. By the time it crossed into North America as the NES in 1985, Nintendo had not just resurrected the video game market—it had become its undisputed master.

Nintendo entered a skeptical U.S. market in 1985, following the disastrous crash of 1983 with a console that was anything but ordinary. The NES bundled Super Mario Bros. and Duck Hunt, established a strict seal of quality, and sparked a pop‑culture storm. Uemura later reflected on the system’s unexpected success:

“I didn’t have time to think about success, because I was so busy taking care of a lot of issues and technical problems…”

Masayuki Uemura, Nintendo

In less than a decade, Nintendo sold over 60 million NES units and turned franchises like Zelda, Metroid, and Punch‑Out!! into global phenomena. With its tightly controlled licensing and vertical integration, Nintendo became the gatekeeper of quality in 8-bit home gaming. At the height of its power, third-party titans Capcom, Konami, Squaresoft, and Enix all aligned under Nintendo’s banner.

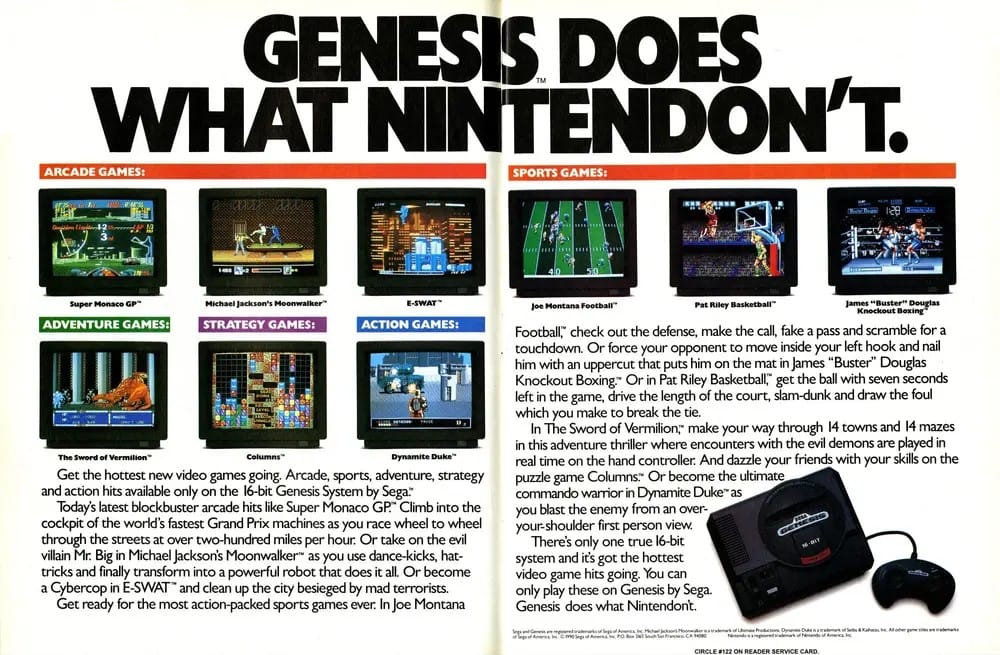

Yet beneath the dominance, tectonic shifts were stirring. Gamers grew older, expectations climbed, and whispers of 16-bit opponents offered vivid new possibilities. By the late 1980s, the NES—once cutting-edge—feels increasingly dated. Gamers demanded higher resolutions, richer sound, more layers, and smoother scrolling. Sega’s “Genesis does what Nintendon’t” campaign capitalized on that appetite, positioning the Genesis as edgier and more modern.

Rival systems like NEC’s PC Engine teased the power of 16-bit computing. Nintendo, despite its market grip, recognized the threat—and the opportunity. The industry was no longer chasing Nintendo; it was catching up. The stage was set for Nintendo’s next act. Blockbuster first-party makers were anxiously watching. Third‑party developers were flirting with richer hardware. Consumers wanted spectacle.

Nintendo’s answer: not another incremental step, but a reimagined foundation for the future of console gaming—the Super Famicom, engineered to excel where the NES had limitations. A platform where audio, visuals, and gameplay harmony mattered more than clock speed.

Building the Beast – The Birth of the Super Famicom

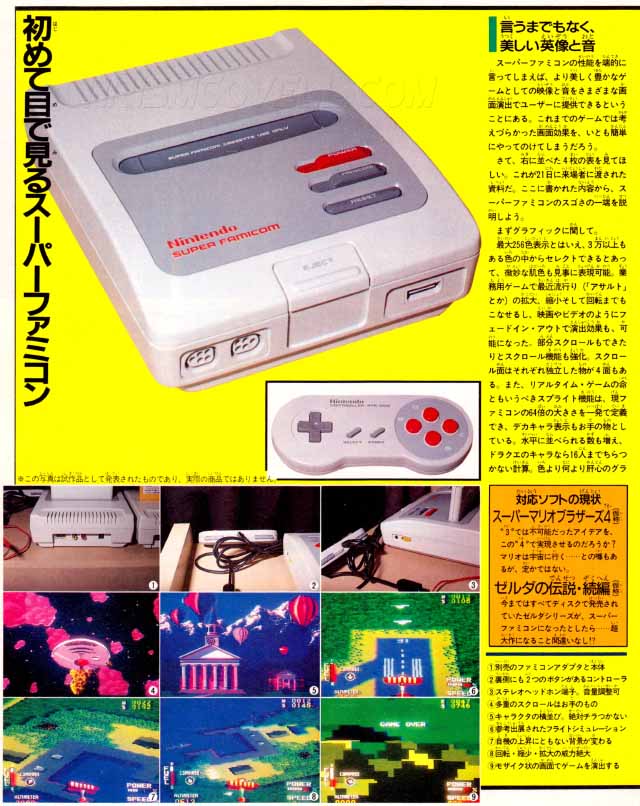

Before the world knew the Super Nintendo Entertainment System as a global phenomenon, it began as a quiet skunkworks project in Kyoto — a machine built not for raw speed, but for spectacle, sound, and staying power. The Super Famicom wasn’t just a technical upgrade over the Famicom; it was a bold reimagining of what home consoles could deliver.

The architect of the original Famicom, Masayuki Uemura, had retired — but only briefly. When it came time to design Nintendo’s 16-bit follow-up, company president Hiroshi Yamauchi asked Uemura to return to the drawing board. He accepted the challenge, and in 1988, development began in earnest.

That same year, the first images of the system appeared in Japan’s Famicom Tsūshin magazine. Nintendo had no intention of losing ground in the post-NES era. The next console had to be a technological leap — but not at the cost of accessibility or game design principles. Uemura’s design philosophy prioritized audio and visual excellence over raw processing horsepower.

| Feature | Famicom (NES) | Super Famicom (SNES) |

| CPU | Ricoh 2A03 (8-bit MOS Technology 6502 core) @ 1.79 MHz (NTSC) | Ricoh 5A22 (16-bit WDC 65C816 derivative) @ 3.58 MHz (nominal) |

| Work RAM | 2KB | 64KB (for video data), 544 bytes (OAM for sprite data), 256×15 bits (CGRAM for palette data) |

| Video RAM | 2KB | 64KB (PPU SRAM) (Note: SNES-CD prototype had 256KB additional work RAM) |

| Display Resolution | 256×240 pixels | 256×240 pixels (with advanced effects) |

| Color Palette | 53 colors total, 25 on-screen | 32,768 colors total, up to 256 on-screen |

| Audio Channels | 5 channels (2 pulse, triangle, white noise, DPCM) | 8-channel ADPCM audio (stereo sound) |

| Key Features | Basic graphics, limited sound | Mode 7, hardware scaling/rotation, dedicated sound co-processor, cartridge enhancement chips (Super FX, DSP) |

At the heart of the Super Famicom was the Ricoh 5A22, a custom chip based on the 65816 CPU developed by Western Design Center. This same family of processors had deep historical roots: the 65816 was a descendant of the legendary MOS 6502, the same chip used in the Apple II, the Atari 2600, and — crucially — the original Famicom.

Because of this shared DNA, early SNES development was done using modified Apple II computers, a fitting nod to its ancestry. The 5A22 ran at a modest 3.58 MHz, significantly slower than the Motorola 68000 chip found in the Sega Genesis. But that was never the point. Uemura believed that the experience — the color, the sound, the flexibility — would set Nintendo’s console apart.

The SNES’s strengths lay not in brute force but in versatility and polish. It could display up to 128 sprites on screen at once, with multiple sizes and priorities. It supported 4 background layers and a total palette of 32,768 colors, up to 256 of which could be used on a single screen.

Its visual modes — eight in total — gave developers a range of tools to manipulate how games were drawn and layered. The final mode, Mode 7, would become a pop-cultural legend thanks to its ability to create rotating, scaling, pseudo-3D backgrounds.

This technical flexibility gave SNES developers the illusion of depth and motion — tools that could simulate racing tracks, flight simulators, or even globe-spinning map screens in RPGs. It wasn’t real 3D, but in 1990, it felt like magic.

Perhaps the most surprising inclusion in the SNES hardware was its audio subsystem, designed in part by a man who would one day become Nintendo’s greatest rival. Ken Kutaragi, the “Father of PlayStation,” secretly worked on the Sony SPC700 chip, a dedicated 8-bit audio processor capable of handling 8 simultaneous 16-bit audio channels.

Working alongside a digital signal processor (DSP), this co-chip system allowed for crystal-clear stereo sound, reverb, and sampling unlike anything else on the market. The Genesis had a headphone jack — but the SNES had orchestration. Composers like Koji Kondo, Yuzo Koshiro, and Nobuo Uematsu thrived on this silicon symphony.

Nintendo didn’t just innovate inside the console — it rewrote the rules of player input too. The SNES controller retained the Famicom’s beloved D-pad, but expanded its face buttons to A, B, X, and Y, arranged in a diamond layout that would influence generations of controllers to come.

More importantly, it introduced the world to the L and R shoulder buttons, a subtle but transformative addition that opened the door to new gameplay mechanics — from strafing in shooters to item cycling in RPGs. Its rounded ergonomic shape also moved past the angular discomfort of its predecessors.

Nintendo’s Quiet New Competitor

Even before Nintendo unveiled the Super Famicom, another Japanese company was quietly crafting technology that echoed what would later become Nintendo’s flagship console. That company was Hudson Soft, with a vision built around Bee Card technology and ambitious hardware dreams—and their failure to win Nintendo’s trust dramatically shaped gaming history.

Hudson Soft, convinced they were holding lightning in a silicon bottle, approached Nintendo. But Nintendo, still riding high on the Famicom’s success and focused on expanding into Europe and enhancing existing cartridges with MMC chips, gave a polite but firm “No thanks.”

Hudson’s rejection by Nintendo didn’t impede their ambition—it fueled it. With no partnership forthcoming, they turned to NEC, which embraced the idea of a modern home console powered by Bee Card–derived hardware. This collaboration led to the creation of the PC Engine, marking Hudson’s exit from licensing merely software to designing core hardware. Meanwhile, Nintendo doubled down on its own designs, missing a chance at early 16-bit innovation.

The resulting PC Engine, released in Japan on October 30, 1987, astonished the market. Its compact design and arcade-like performance made it Japan’s best-selling console by late 1988, even outpacing the Famicom in monthly sales at its peak.

At its heart was the refined HuCard—derived from Hudson’s Bee Card concept—with a PCB encased in glossy polymer and 38 connectors. It was both stylish and functional, laying the groundwork for a hardware revolution that directly competed with everything Nintendo had built.

Namco, Konami, and other top-tier developers flocked to the platform, enticed by less restrictive licensing and greater hardware flexibility. The once-ignored licensing overlord—Nintendo—was now staring down a legitimate challenger born from its own refuted ideas.

The Launch of the SNES

While Sega sprinted out of the gate in 1989 with its 16-bit Genesis, Nintendo took its time. The company wasn’t interested in a reactionary console—it was quietly crafting something more sophisticated. A machine not just to compete, but to elevate.

That “something” finally arrived in American stores during the fourth week of August 1991—nearly two years after both the Sega Genesis and the TurboGrafx-16 had debuted. To longtime Nintendo fans, the Super Nintendo Entertainment System was a long-awaited second coming. To parents? It was an expensive mystery.

At $199.99, the SNES launched at a full $50 more than the discounted Genesis, and twice the price of the NES, which was still going strong in households across the country. For many parents—who didn’t understand why Super Mario World couldn’t run on the NES they’d already bought—it felt like a shakedown.

But Nintendo had never been about bargain bins. The SNES wasn’t meant to be cheap—it was designed to be transformative. At the time of launch, the TurboGrafx-16 was already fading from relevance, failing to build the cultural foothold it had secured in Japan. But Sega? They were prevailing. The Genesis was just starting to hit its stride in North America, and for once, Nintendo wasn’t going to be the first to strike.

Sega capitalized on this timing with ruthless precision. The company’s sleek new mascot, Sonic the Hedgehog, sped into American stores just in time to beat the Super Nintendo to market—a deliberate strategy to rebrand Sega as the cooler, faster, more “radical” alternative to Nintendo’s perceived conservatism. Up until this point, Sega had been fighting an 8-bit giant with a 16-bit sword, but now, with the SNES officially on the battlefield, the console wars were about to become a true clash of titans.

Nintendo had entered the ring not just with hardware, but with intent—a next-gen platform designed to wow with audiovisual finesse, an iconic pack-in (Super Mario World), and a library poised to redefine what console gaming could be. The race was officially on. But Nintendo, as always, wasn’t sprinting. It was playing the long game.

The Console Wars – SNES vs. Genesis

On one side: Nintendo, the reigning monarch of the video game world. Polished. Deliberate. Backed by legacy and name recognition. On the other: Sega—the insurgent upstart with swagger, speed, and a chip on its shoulder the size of Green Hill Zone.This was more than a marketing rivalry. This was the Console Wars, and it was fought in magazine ads, playground debates, and living rooms around the globe.

Sega drew first blood with one of the most iconic digs in gaming history: “Genesis does what Nintendon’t.” It was snarky. It was aggressive. And it worked. The Genesis quickly branded itself as the cooler, older sibling—faster, louder, edgier. Sonic the Hedgehog, a blue blur with ‘tude, felt ripped straight from MTV’s playbook. Sega wasn’t just selling games—it was selling rebellion.

Meanwhile, Nintendo still wore the image of Saturday morning cartoons and cereal box tie-ins. For all its power, the SNES carried a reputation as the “safe” option—a console for kids who still watched The Super Mario Bros. Super Show.

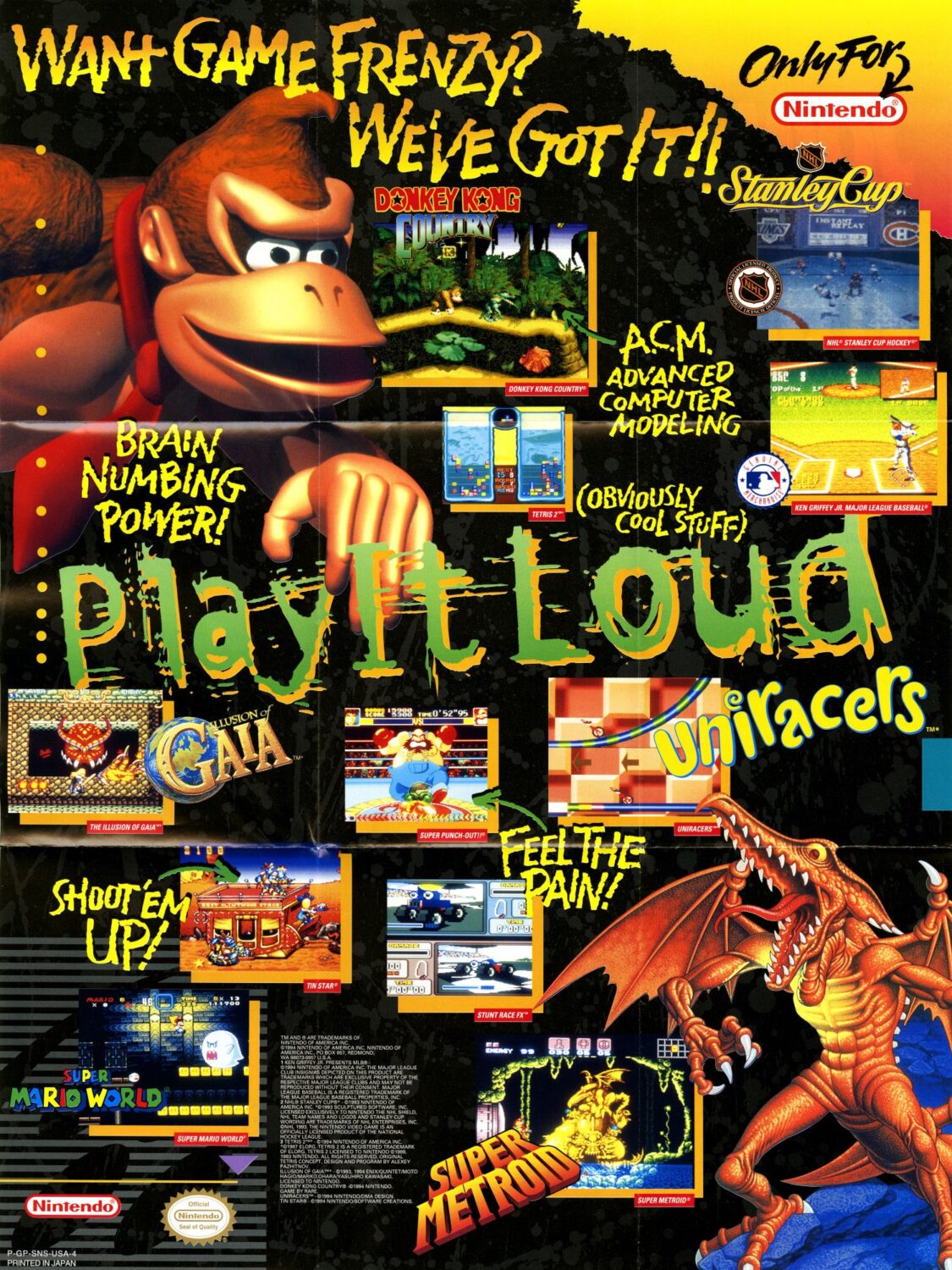

That perception began to shift between 1991 and 1992, as Nintendo’s marketing evolved to meet the challenge. It all culminated in the brash, controversial Play It Loud campaign of 1994—a far cry from Mushroom Kingdom wholesomeness. The ads were drenched in punk rock, grungy skateboarders, trespassing teens, and anti-authority angst. Nintendo was trying to shout what Sega had been whispering for years: “We’re not just for kids anymore.”

The campaign lasted roughly six months before Nintendo beat a hasty retreat to its more conservative roots. The punk rebellion might not have stuck, but it was proof the company was paying attention. This war demanded more than mushroom power-ups—it required attitude. But this was never just about speed or slogans. It was about games, and who had the best ones.

And here, Nintendo struck back hard. With Capcom, Square, Konami, Enix, and Namco on its side, the SNES became a first-party fortress and a third-party goldmine. Final Fantasy VI. Mega Man X. ActRaiser. Secret of Mana. These weren’t just hits. They were genre-defining, generation-defining titles.

Sega, increasingly aware of its slipping market share by 1993, launched a counteroffensive with hardware: the Sega CD. CD-ROM technology promised massive games, full-motion video, and “the future”—right now.

Nintendo themselves were also interesting in explore its own CD-ROM add-on. That interest would lead directly to a handshake deal… and one of the most dramatic betrayals in gaming history.

The Nintendo PlayStation Fiasco

Nintendo looked to expand the Super Famicom’s capabilities with a CD-ROM add-on. Partnering with Sony seemed natural—after all, they had already proven reliable collaborators.

The result was the SNES-CD project, with internal prototypes labeled “Play Station.” It was a chimera: a hybrid console that could play both SNES cartridges and a new “Super Disc” format. Sony saw an opportunity to control the emerging CD standard in gaming. Nintendo, however, saw something more dangerous: a partner becoming too powerful.

An internal memo from the time reportedly expressed concern that “Sony would control the software pipeline.” That was a line Nintendo, a company deeply protective of its licensing model, wouldn’t cross. In June 1991, at the height of anticipation, Sony confidently unveiled its SNES-CD prototype at the Consumer Electronics Show. But the celebration was short-lived. The very next day, Nintendo stunned the industry by announcing a new deal with Dutch electronics giant Philips.

This wasn’t a quiet corporate reshuffle—it was a public betrayal.

Howard Lincoln, then chairman of Nintendo of America, attempted to frame the decision as “in the best interest of consumers,” but the move sent shockwaves through the tech world. Nintendo had effectively walked out on Sony mid-project, stripping them of the ability to publish SNES-CD software and cutting them out of the very ecosystem they had helped build.

A senior Sony exec reportedly said at the time: “They used us to get what they wanted, and then they walked.” Instead of backing down, Sony doubled down. Kutaragi, who many considered a “loose cannon” within Sony just years earlier, was given the green light to rework the failed SNES-CD prototype into a standalone console. His vision was clear: a new 32-bit machine that prioritized 3D graphics, CD-ROMs, and developer freedom. The PlayStation was born.

The Nintendo–Sony fallout didn’t just change two companies. It changed the entire industry. Nintendo underestimated Sony’s resolve, and in doing so, helped create the very competitor that would dethrone them. In a story filled with what-ifs and strategic misfires, this is the moment where the console wars were irreversibly changed—not in the courtroom or boardroom, but on a show floor in 1991.

The SNES Library – Where Legends Were Born

If the NES gave us Super Mario Bros. as a revolution, then Super Mario World was its refinement into perfection. Launching alongside the Super Famicom in 1990, it showcased everything the SNES could do: larger sprites, richer backgrounds, multilayered scrolling, and an unforgettable new companion—Yoshi.

“With Super Mario World, we wanted to create a game that felt like a theme park. Each area should surprise and delight you.”

Shigeru Miyamoto, Nintendo

The overworld map introduced new layers of exploration, while hidden exits and secret worlds hinted at Nintendo’s growing obsession with replayability.

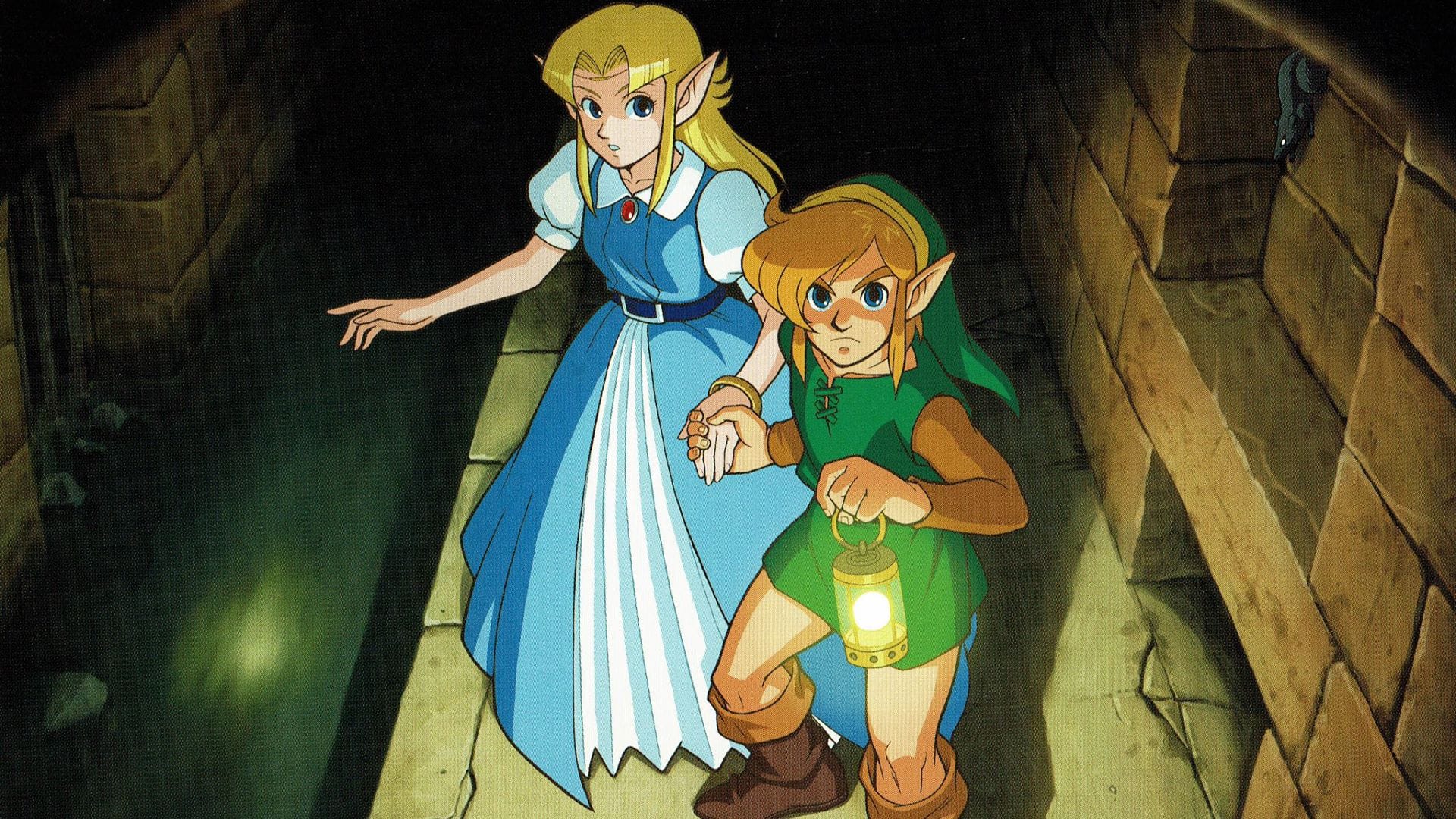

The third entry in the Zelda franchise was, for many, the definitive one. A Link to the Past set the tone, structure, and spirit of the series for decades to come. Dual-world mechanics, environmental storytelling, and smart dungeon design combined into an experience that felt mythic. Shigeru Miyamoto said of the project, “We wanted to make a game that felt like a legend passed down through generations.”

With its sweeping soundtrack, intricate puzzles, and a world brimming with mystery, it felt exactly that. Even today, modern Zelda games—from A Link Between Worlds to Tears of the Kingdom—owe their DNA to this 16-bit masterpiece.

The SNES became the home of JRPGs, nurturing a genre that blossomed into art. Final Fantasy IV (released as II in North America) brought operatic drama, fully fleshed-out characters, and the now-iconic Active Time Battle system. Suddenly, RPGs were no longer niche—they were narrative experiences.

Then came Chrono Trigger, a dream project by the “Dream Team”: Hironobu Sakaguchi, Yuji Horii, and Akira Toriyama. Its nonlinear story, time-traveling mechanics, and multiple endings felt radical for the era. It was the rare RPG where your choices truly mattered. As one EGM reviewer wrote in 1995, “Chrono Trigger doesn’t just raise the bar—it builds a whole new one.”

In 1994, with the 32-bit era on the horizon, everyone thought the SNES had peaked. Then Rare, a British developer working with proprietary Silicon Graphics technology, released Donkey Kong Country. It wasn’t just a hit—it was a shockwave.

Nintendo Power called it “next-gen graphics on current-gen hardware.” The pre-rendered 3D visuals made jaws drop, but beneath the surface was a tight, challenging platformer with a funky jungle vibe and pitch-perfect controls. It proved that the SNES wasn’t obsolete—it was still evolving.

Before Mario 64, before the PlayStation, there was Star Fox. Released in 1993, it was the SNES’s boldest technical gamble: a fully 3D shooter powered by the Super FX chip—a custom processor embedded directly in the cartridge. Developed with Argonaut Software, the game introduced console players to real-time polygonal graphics and cinematic camera angles. And while blocky by today’s standards, Star Fox felt like science fiction at the time.

In an interview, programmer Dylan Cuthbert said, “We were trying to do something on a 16-bit system that people said couldn’t be done. And then we did it.”

What makes the SNES library endure isn’t just nostalgia—it’s design integrity. These games were built under tight memory constraints and technical limits, but instead of feeling dated, they feel distilled. Pure. Polished. Controls were intuitive. Art direction was tailored to the hardware’s strengths. Music wasn’t just background noise—it was emotionally resonant.

Every game, from EarthBound to Super Metroid, felt handcrafted. The SNES era taught an essential lesson: great games aren’t defined by resolution—they’re defined by vision.

Cultural Icon Status Secured

By the mid-1990s, “Nintendo” wasn’t just a company—it was a verb.

Even if your household had a Sega Genesis or a TurboGrafx-16, chances are you still said you were “playing Nintendo.” That’s how deep the SNES had embedded itself into pop culture. Like Band-Aid or Kleenex, it became shorthand for the medium it dominated.

The SNES didn’t just ride the wave of success created by the NES—it surpassed it. It proved that lightning could strike twice and that Nintendo wasn’t a one-hit wonder. The characters it housed—Mario, Link, Samus, Donkey Kong—had evolved into cultural mascots. They weren’t just in video games. They were in lunchboxes, cartoons, cereal boxes, and backpacks.

As Time magazine wrote in a 1993 feature: “Nintendo’s world isn’t just on your screen—it’s in your home, in your language, and in your head.”

Before Reddit threads and YouTube lore explainers, there was Nintendo Power. The official magazine didn’t just promote games—it cultivated a community. Kids obsessed over fold-out maps, tip hotlines, and Howard & Nester comics. It was the internet before the internet: a lifeline to the games we loved and the secrets they hid.

But Nintendo fandom didn’t stop at magazines. You could find Mario bedsheets at Sears, Link figurines at KB Toys, and SNES commercials airing during Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. There were strategy guides as thick as textbooks, tournaments at malls, and a Saturday morning cartoon block that proudly said: “It’s on like Donkey Kong.” This wasn’t just marketing—it was myth-making.

One quote from a 1994 GamePro reader mailbag captured it perfectly: “I don’t want to just play the games—I want to live in them.”

You’d think a 16-bit console released in 1990 would feel ancient today. But instead, the SNES remains eerily timeless. Part of this is design: SNES games are easy to pick up and hard to put down. The visuals are bright and readable, the music is melodic and memorable, and the gameplay mechanics remain shockingly elegant. Games like Super Metroid, Kirby Super Star, and Tetris Attack still feel crisp and complete, no patches required.

But the deeper reason is emotional. These games carry texture—the feeling of pressing down the reset button, of blowing into a cartridge, of arguing over which controller port was “player one.” They represent an era where creativity had to overcome constraint, and that tension led to brilliance.

The SNES wasn’t just a machine. It was a moment—a cultural apex that defined childhoods, launched careers, and rewired the public’s understanding of what interactive entertainment could be. It was art. It was business. It was identity. It still is. And that’s why, more than three decades later, the SNES isn’t just remembered. It’s revered.

The SNES’s Lasting Legacy on Game Design

The SNES may have been a leap forward in power, but it wasn’t without limits. In fact, those limits defined some of its greatest innovations.

With only 128KB of RAM and strict cartridge size restrictions, developers couldn’t afford to be wasteful. So they got clever. Sprite reuse, Mode 7 trickery, layered parallax scrolling—these weren’t just aesthetic flourishes, they were necessities. Titles like Super Metroid and Chrono Trigger used environmental design and minimalist dialogue to create atmosphere not through quantity, but through precision.

As Shigeru Miyamoto once put it, “A good idea is something that does not solve just one single problem, but rather can solve multiple problems at once.” SNES games embodied this ethos—designing around limitations rather than being broken by them.

If the NES gave us the chiptune era, the SNES gave us cinematic soundscapes. The onboard Sony SPC700 sound chip, driven by the genius of Ken Kutaragi (yes, that Kutaragi), offered composers 8 audio channels, sample-based synthesis, and the freedom to finally paint with sound.

And paint they did. Koji Kondo’s score for A Link to the Past is an operatic journey that moves from triumphant to haunting in a single phrase. Kenji Yamamoto’s Super Metroid soundtrack is minimalist, ambient, even oppressive—turning a silent bounty hunter into an emotional protagonist through audio alone.

The SNES taught developers that music wasn’t background—it was narrative.

From Super Mario World’s buttery-tight controls to the layered tactical nuance of Final Fantasy VI, the SNES era drilled one lesson into the industry’s DNA: gameplay is king.

This was an era before day-one patches, before massive open worlds filled with fluff. Every pixel, every jump arc, every combat encounter had to be just right—because it had to last. Games weren’t built to be binged and forgotten. They were made to be played, replayed, and remembered.

Even today, developers from indie creators to AAA teams cite SNES titles as touchstones of pure design elegance. Nintendo’s internal mantra of “fun first” became an industry-wide aspiration.

It had four face buttons. Two shoulder buttons. Ergonomic curves. The SNES controller wasn’t just a peripheral—it was a blueprint. Sony’s DualShock? Xbox’s gamepad? The Switch Pro Controller? All of them trace their DNA back to that rounded, purple-and-lavender rectangle. The SNES controller was a distillation of everything that worked about the NES pad, with just enough innovation to future-proof an entire generation of input design.

Nintendo may have redefined gamepads, but the rest of the world followed. Decades later, it remains the template, not the relic.

The SNES didn’t just deliver hits. It laid the groundwork for how games are made, played, and remembered. Its limitations birthed brilliance. Its sound became story. Its gameplay raised the bar. And its controller? Still the standard-bearer. Game design owes a profound debt to this unassuming grey-and-purple box. And in many ways, it’s still repaying it.

Nintendo’s Obsession with Control: Strength or Weakness?

From the Famicom to the SNES, Nintendo wasn’t just a console manufacturer—it was a gatekeeper. Hardware, software, licensing, branding—it all passed through Kyoto’s filters. Nintendo set the rules, and the industry played along.

And it worked. The SNES thrived under that model. Nintendo’s seal of quality became a symbol of trust. But behind the curtain, there was friction—strict licensing contracts, censorship policies, and a growing tension between creative freedom and corporate conservatism.

Nintendo’s control ensured polish, yes—but it also bred resentment.

As one ex-Konami producer told EDGE magazine in 1998: “Working with Nintendo in the ‘90s meant checking your ego at the door. They owned the hallway, and you were lucky to rent a room.” This obsession with control would become both Nintendo’s shield and its shackle in the years to come.

The SNES era was defined by cartridges—sturdy, fast-loading, and profitable for Nintendo’s bottom line. But when the industry began shifting to CD-ROM, with its greater storage and lower costs, Nintendo refused to budge.

Why? Control. CD formats would give developers more freedom, more data, and more autonomy. Nintendo didn’t want that. They doubled down on cartridges for the N64—and while it led to blisteringly fast gameplay (Super Mario 64, GoldenEye), it also led to an exodus.

Square. Capcom. Enix. Namco. The titans of the SNES generation jumped ship to Sony, whose new PlayStation offered cheaper production, higher capacity, and none of Nintendo’s iron grip.

“Nintendo won the battle of the ‘90s, but the war is moving to CD—and they’ve brought a sword to a gunfight.”

Next Generation Magazine, 1997

Let’s rewind. Had the SNES-CD partnership with Sony gone through, Nintendo could have launched a 32-bit, disc-based console years before the PlayStation. Instead, they bailed—publicly humiliating Sony at CES 1991 by announcing a partnership with Philips instead.

Sony didn’t forget. Their consumer electronics power and developer-friendly approach led to the PlayStation boom. By 1996, Nintendo wasn’t just facing competition—they were facing domination.

The SNES was a triumph—but triumph can breed tunnel vision. Flush with success, Nintendo doubled down on its most defining trait: control. It controlled the hardware. The software. The supply chain. Even the developers. That tight grip had worked wonders in the 8- and 16-bit eras. But as the industry evolved, that same grip began to strangle innovation.

In the long shadow of the SNES, Nintendo would learn to reinvent itself—sometimes painfully, sometimes brilliantly. And in doing so, it would remain the most unpredictable force in gaming, shaped as much by its scars as its victories.

Conclusion

The Super Nintendo wasn’t just another console on the shelf—it was a revolution in a plastic shell. It redefined what home gaming could be, marrying technical finesse with artistic ambition. Mode 7 may have been a technical gimmick, but it brought worlds to life in ways that once seemed impossible. The controller reshaped how we interacted with games. And the library? A pantheon of masterpieces, from Super Metroid to Chrono Trigger, each one still studied, dissected, and celebrated to this day.

But the SNES’s impact isn’t confined to the past. Its DNA runs through every side-scrolling indie darling, every pixel-perfect homage, and every orchestral game soundtrack. It set the template not just for how games could look—but how they could feel, how they could sound, and how they could mean something.

This isn’t just nostalgia talking. The SNES remains a living blueprint—a reminder that thoughtful limitations can fuel innovation, that artistry thrives within constraint, and that great game design is, at its core, timeless.