There’s a certain melancholy to the PS Vita. A machine brimming with audacity, elegance, and raw horsepower—yet destined to languish in the shadows. When Sony unveiled its sleek successor to the PSP, it promised nothing short of a portable revolution: twin analog sticks, an OLED display that rivaled living room televisions, and the kind of technical brawn whispered about in the same breath as the Xbox 360.

On paper, it was a dream. In practice, it became one of gaming’s great paradoxes. The Vita wasn’t just another handheld; it was a declaration that portable gaming could stand shoulder-to-shoulder with consoles. But hubris, timing, and an unforgiving market transformed that promise into heartbreak. The result? A system remembered less for its sales figures and more for its cult devotion—a console that failed spectacularly, yet remains unmatched in what it dared to achieve.

The PSP2 Whispers Begin

By the late 2000s, the PSP had carved out its place as more than just a Nintendo rival—it was proof that Sony could make handhelds feel like premium tech. But whispers of something bigger began surfacing around 2009. Industry insiders murmured about a “PSP2,” a machine supposedly bristling with enough power to rival home consoles. At first, it sounded like vaporware. Then the smoke thickened.

Tokyo, September 2010. While the show floor of the Tokyo Game Show buzzed with the usual spectacle—booths blaring, cosplayers roaming, and demo stations jammed with eager fans—something quieter was happening behind the curtain. In a discreet conference room far from the crowds, Sony had gathered a select handful of publishers and partners. What they saw was not for public eyes.

The prototype laid out before them was unlike anything the handheld market had seen. A gleaming screen, twin analog sticks, forward and rear cameras, even a mysterious rear touchpad. It looked futuristic, daring—almost impossible for portable hardware at the time. Sony executives spoke of ambition, of merging the convenience of handheld play with the scale and fidelity of console gaming. For the chosen few in that room, the PSP2 wasn’t just a rumor anymore; it was a promise of things to come.

Whispers of the closed-door session spread fast, carried by journalists and developers who couldn’t quite keep the secret. The sense of inevitability grew. The next great Sony handheld was no longer a matter of if—it was simply a matter of when.

The speculation reached fever pitch when photos of a bulky dev kit surfaced online. It was ugly, industrial, and experimental—a handheld with a sliding screen like the PSP Go, twin sticks jutting out, and the raw ambition of something built to outpace everything before it. The PSP2 wasn’t a rumor anymore. It was real. And the gaming world braced itself.

The secrecy didn’t last long. By late 2010, developers began to quietly confirm what many already suspected: Sony’s new handheld was real, and it was already in their hands. Software development kits had been shipped out, and studios were beginning to experiment with what the hardware could do. Some couldn’t resist dropping hints. Others were less subtle.

“Well, obviously as a developer we have had that–but I’m not allowed to talk about it…We can’t talk about it because of our relationship with Sony obviously, which is… That’s just the way it is.”

Patrick Söderlund, Senior Vice President of EA

The damage was done. Sony could deny all it wanted, but one of the industry’s biggest publishers had more or less confirmed the machine’s existence. Not long after, grainy photos of an early development kit began circulating online. It wasn’t pretty—an experimental unit with a sliding screen reminiscent of the PSP Go, oversized and unfinished. Yet the promise was unmistakable. Twin analog sticks. An HD display. A back touchpad. The kind of horsepower whispered to rival the Xbox 360. For fans starved for a true successor to the PSP, these leaks were enough to ignite a frenzy. The PSP2 was no longer just a rumor; it was a looming reality.

Sony’s early vision for the PSP2 was bold, perhaps even too bold. The first wave of development kits featured a striking sliding-screen design, not unlike the short-lived PSP Go. It looked futuristic, with the promise of collapsing into a compact shape that could easily slip into a bag or pocket. But the ambition came at a cost. Developers quickly discovered that the prototype ran hot—too hot. The sleek slider couldn’t handle the raw power Sony was cramming inside.

Practicality won out. The sliding mechanism was abandoned, and the engineers went back to a more familiar form factor. The final design evoked the sturdy PSP-1000, but this time with the flourishes that fans had long begged for: dual analog sticks, a larger high-resolution screen, and an array of forward-thinking features that stretched beyond gaming. Cameras on the front and back. A mysterious rear touchpad that invited new control possibilities. And at the heart of it all, an OLED display that was jaw-droppingly vibrant, the kind of screen usually reserved for top-end smartphones and HDTVs.

What had started as an experimental shape-shifter was now a refined powerhouse. Sleek, comfortable, and unapologetically premium, Sony’s “dream machine” was finally ready to step out of the shadows.

The Official Reveal – NGP Takes the Stage

January 27, 2011. In a Tokyo auditorium packed with journalists and industry insiders, Sony finally pulled the curtain back. The codename was simple yet ambitious: Next Generation Portable—NGP for short. After years of whispers, leaks, and speculation, the world was officially introduced to Sony’s bold new handheld.

The presentation was nothing if not theatrical. Kaz Hirai took the stage with the air of someone who knew exactly what he was holding. To him, the NGP wasn’t just another handheld—it was a philosophy made tangible. His pitch was simple but compelling: why choose between the immediacy of smartphone touch gaming and the depth of traditional console experiences when you could have both?

The device embodied that vision. On one side, there were the features built to court a new generation of players—an expansive touchscreen, rear touchpad, motion controls, cameras, and even augmented reality. On the other, the tried-and-true elements that defined PlayStation: physical buttons, a proper D-pad, and, at long last, dual analog sticks. It wasn’t about abandoning the old guard for mobile trends, nor about ignoring the cultural wave of touch-based play. It was about unifying them under one machine.

If Kaz Hirai sold the vision, Shuhei Yoshida sold the dream. When the head of Sony Worldwide Studios walked on stage, he came armed with the kind of proof every gamer wanted to see: the games. What followed was a rapid-fire showcase that instantly reframed what a handheld could deliver.

First up was Uncharted: Golden Abyss. Seeing Nathan Drake scale cliffs and trade gunfire on a portable screen felt almost surreal. It wasn’t a cut-down spin-off or a watered-down experiment—it was a fully-fledged Uncharted adventure, rendered with detail that seemed impossible outside of a living room console. The demo even leaned into the Vita’s unique features, with Drake shimmying up ropes via swipes on the rear touchpad.

Then came Little Deviants, a quirky original project built entirely around the back touchpad, where players manipulated the environment itself rather than the characters. It was playful, strange, and exactly the kind of experiment that hinted at the Vita’s potential beyond traditional gameplay.

Familiar faces followed: Hot Shots Golf swinging onto the handheld with its signature charm, and WipEout blazing across the OLED with blistering speed. Each reveal reinforced the same point—the NGP wasn’t dabbling in console-quality experiences. It was delivering them wholesale, right in the palm of your hand. For many watching, this was the moment belief turned into excitement.

As if the hardware and first-party lineup weren’t enough, Sony doubled down by parading a roster of heavyweight publishers across the stage. Sega, Capcom, Activision—names synonymous with blockbuster franchises—all pledged allegiance to the new handheld. Their presence wasn’t just symbolic; it was reassurance that the NGP wouldn’t suffer the fate of being a first-party island.

Capcom impressed with Monster Hunter Portable 3 running on the device, showcasing backward compatibility with digital PSP titles while hinting at a possible future for the franchise on Vita. Sega signaled intent by teasing its slate of titles, reminding everyone of the company’s long history of supporting cutting-edge hardware. Activision added extra firepower, touting the promise of bringing its massive properties to Sony’s pocket-sized powerhouse.

This united front gave the impression of inevitability. If the biggest publishers in the industry were already on board, surely the Vita was destined for greatness. For a brief, shining moment, the stars seemed aligned—hardware ambition, strong launch games, and the backing of gaming’s biggest players. Sony wasn’t just promising a handheld. It was promising a portable PlayStation 3 in your pocket.

Rebranding and a Big Promise – Enter the PlayStation Vita

When E3 2011 rolled around, Sony was ready to put a permanent name to its ambitious handheld. Gone was the codename NGP. In its place stood a title that felt sleek, modern, and aspirational: PlayStation Vita. Latin for “life,” the name carried a bold implication—that this wasn’t just a console, but a lifestyle companion, a device meant to live alongside you.

The presentation was confident, almost defiant. Sony unveiled the Vita’s official branding with a flurry of game demos, hardware showcases, and the promise of seamless connectivity. And then came the reveal that drew an audible gasp from the audience: the price. $249 for the Wi-Fi model, $299 for the 3G variant. In a year when Nintendo had stumbled with the 3DS’ $249 launch, Sony’s pricing strategy felt like a calculated strike—a message that the Vita could match its rival’s cost while delivering far more power and features.

On stage at E3, Sony unveiled a feature that seemed ripped from the future: cross-play. The demo came courtesy of an action-RPG then known as Ruin (later rebranded Warrior’s Lair), and it promised something console players had only daydreamed about—seamless save transfers between the Vita and the PlayStation 3.

The pitch was intoxicating. Start a dungeon crawl on your PS3, pause, then pick up your Vita on the train and resume right where you left off. No compromises, no stripped-down version, just your full game following you wherever you went. In an era before cloud gaming became an industry buzzword, this was revolutionary. The crowd responded with real awe, not just polite applause.

For that moment on stage, it seemed Sony had learned from past mistakes. The Vita had a strong name, an alluring price point, and a portfolio of games that looked like a greatest-hits package. It was the kind of E3 announcement that left even skeptics wondering if Sony had just stolen the show.

The Launch of the PS Vita

On December 17, 2011, Japanese gamers were treated to a launch lineup that was nothing short of staggering: 26 titles on day one. It was the kind of breadth that made the Nintendo 3DS’s sluggish start look downright anemic. The excitement translated into immediate sales, with over 300,000 units snapped up during the first week. For a brief, shining moment, it seemed like Sony had a runaway hit on its hands.

But the honeymoon ended fast. By the second week, sales cratered to fewer than 75,000 units. By week three, the Vita was being outsold not just by the Nintendo 3DS, but by the aging PSP—a humiliating reversal for Sony’s would-be successor. The high entry cost, pricey proprietary memory cards, and a lack of must-have Japanese exclusives all combined to sap the early momentum. What looked like a dream debut suddenly resembled a cautionary tale. The Vita had launched with a roar, but within weeks, doubt was creeping in—and that doubt would soon define its global rollout.

By February 2012, the PlayStation Vita finally touched down in North America and Europe. Sony once again leaned on sheer volume to impress: a launch catalog boasting heavy hitters like Uncharted: Golden Abyss, Lumines: Electronic Symphony, WipEout 2048, and Rayman Origins. On paper, it was one of the strongest handheld debuts ever assembled. The message was clear—this wasn’t a toy, this was a serious machine for serious gamers.

Yet the reception was muted. Initial sales were respectable, but they lacked the explosive energy needed to sustain momentum. Casual audiences were already migrating to smartphones for quick gaming fixes, while core players balked at the Vita’s premium price tag and the infamously expensive proprietary memory cards. Worse still, many marquee titles felt like scaled-down versions of console hits rather than experiences designed to showcase the handheld’s unique strengths.

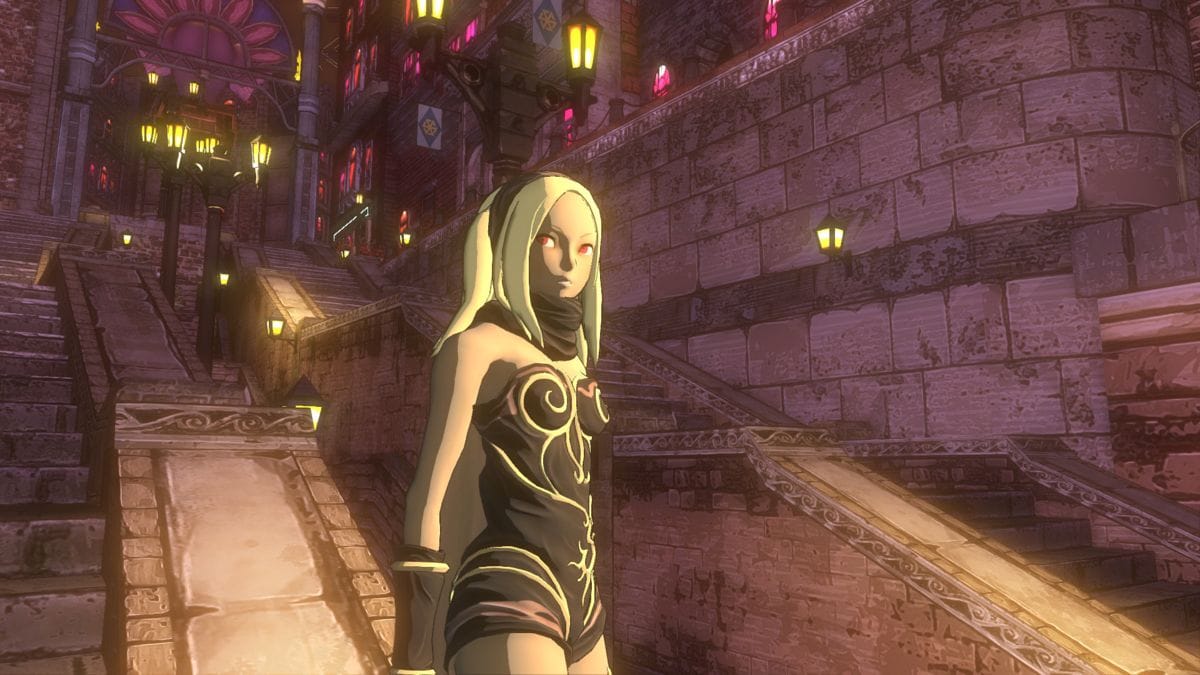

Despite the turbulence, the Vita wasn’t without moments of brilliance. In June 2012, Gravity Rush landed as the system’s first true original must-play. Its gravity-bending mechanics and painterly art style made it feel tailor-made for the handheld, a rare case where the Vita’s hardware and software worked in perfect harmony. Not long after, LittleBigPlanet PS Vita gave players a reason to believe again, marrying the beloved creativity of the series with the touch controls and portability of the device. These weren’t just ports or scaled-down experiments—they were statements of intent.

And for all the headlines about sluggish sales, the Vita quietly crossed an important milestone: 4 million units sold worldwide by the end of its first year. Hardly a runaway success, but far from a disaster in raw numbers. It was proof that there was an audience out there—dedicated, enthusiastic, and hungry for more. The problem was scale. The Vita’s brightest sparks were dazzling, but they couldn’t yet ignite the wildfire Sony so desperately needed.

Just as the Vita began to find its footing, Sony tripped over its own business strategy. Every owner quickly discovered that to download games, save progress, or even run certain titles, you needed a proprietary PlayStation Vita memory card. No SD cards. No cheaper third-party options. Just Sony’s own hardware—and it wasn’t cheap.

A modest 4GB card, barely enough to store a couple of digital titles, costs more than a brand-new 3DS game. The 32GB version, the largest available at launch, was staggeringly expensive, priced higher than many full retail releases. For early adopters, this felt like a hidden tax on top of the handheld’s already steep entry fee.

The backlash was swift. Reviewers flagged the cards as a glaring downside, while players hesitated to dive into digital purchases knowing storage came at such a premium. What could have been a sleek, all-in-one portable gaming device instead carried the stigma of nickel-and-diming. For many, the Vita’s promise dimmed the moment they saw the price tag on those tiny black cards.

Vita’s Second Chance: Remote Play

By 2013, the writing was on the wall. After a year of slipping sales and tepid Western adoption, Sony quietly stopped reporting Vita hardware numbers altogether. It was an omission that spoke volumes—when a company stops bragging about figures, it’s usually because there’s nothing worth bragging about.

The PlayStation 4 loomed large on the horizon, and with it came a shift in corporate priorities. Resources, marketing muscle, and executive attention all funneled toward the shiny new console that promised to restore Sony’s dominance in the living room.

Sony unveiled what seemed like the Vita’s salvation: Remote Play. Suddenly, every PS4 game could be streamed directly onto the handheld’s gorgeous OLED screen. It was a technological marvel, a kind of wizardry that turned the Vita into a pocket-sized portal to blockbuster console experiences.

In practice, the feature worked surprisingly well. Wi-Fi permitting, you could start a game of Infamous: Second Son on your PS4, then continue blasting away from the couch, the kitchen, or even the backyard. For those who tried it, Remote Play felt like a glimpse into the future of gaming.

But novelty alone couldn’t undo the damage. Remote Play was brilliant, yes, but it was never enough to reframe the Vita as essential. It was a companion, not a must-have. Most players still saw the handheld as an expensive add-on rather than a standalone powerhouse. Sony had given the Vita a lifeline—but not a second chance.

Slim Vita and PS Vita TV Arrives

Sony attempted a course correction. A worldwide price cut made the Vita more approachable, while Japan received a redesigned model: the PlayStation Vita 2000. This slimmer, lighter revision trimmed down the hardware and extended battery life—practical improvements aimed at broadening the handheld’s appeal.

But there was a catch. The dazzling OLED display, one of the Vita’s standout features, was swapped for a more cost-effective LCD screen. It made the system cheaper to produce and lighter in hand, but for early adopters, it felt like a downgrade—a subtle admission that the Vita was shifting from premium gadget to budget compromise.

The strategy offered a temporary bump in interest, particularly in Japan where handheld culture thrived, yet it didn’t spark the global turnaround Sony needed. The Vita 2000 was a leaner, friendlier device, but it couldn’t erase the core issue: Sony still hadn’t secured the software pipeline that would make the handheld indispensable.

In late 2013, Sony tried something unexpected: the PS Vita TV. A tiny, minimalist box that plugged straight into a television, it promised access to Vita games, PSP classics, and even Remote Play with the PlayStation 4—all with the convenience of a DualShock controller. On paper, it was a clever repackaging of existing tech, a way to extend the Vita’s ecosystem beyond handheld purists.

Japan embraced the concept at first, with the device selling briskly in its debut week. Yet enthusiasm cooled quickly. Many Vita games relied on touch controls the Vita TV couldn’t replicate, leaving swathes of the library unplayable. Western audiences were even less convinced when the device arrived overseas under the name PlayStation TV. For most, it was a curiosity, not a revolution.

The Vita TV embodied Sony’s restless experimentation—always searching for the angle that might make the handheld indispensable. But like so many of the Vita’s detours, it became another intriguing footnote rather than the breakout success Sony so badly needed.

Signs of Life: Vita Gains Momentum

When Sony’s big-budget ambitions began to fade, two unlikely champions stepped forward to keep the Vita’s pulse alive. Shahid Ahmad, a veteran of Sony’s strategic content division, and Gio Corsi, the larger-than-life head of third-party relations, became the system’s unofficial evangelists. They understood what the hardware faithful already knew: if blockbusters weren’t coming, the Vita could thrive as a haven for inventive, smaller-scale experiences.

Ahmad tirelessly courted indie studios, opening the floodgates for titles like Spelunky, Guacamelee!, and OlliOlli—games that might have struggled for oxygen on home consoles but felt perfectly at home on handheld. Meanwhile, Corsi leveraged his charisma and industry ties to bring cult hits and quirky experiments into the fold. Together, they transformed the Vita’s narrative from one of corporate neglect to grassroots triumph. For players, every new indie announcement felt like a lifeline, proof that the handheld still had fight left in it.

Cross-Buy, Cross-Play, and Cross-Save turned the Vita into more than just a handheld—it became a seamless extension of the PlayStation universe. Buy a game once, and you owned it across Vita, PS3, and later PS4. Pick up your save file on the couch, then continue on the train without missing a beat. In an era where digital storefronts often felt like walled gardens, Sony’s approach was startlingly generous.

Games like Sly Cooper: Thieves in Time and Sound Shapes showcased the vision beautifully, letting players dance between platforms with near-magical fluidity. It was the kind of ecosystem thinking that foreshadowed today’s push for cross-progression and unified accounts across devices. For a fleeting moment, the Vita felt less like an underdog and more like the centerpiece of a forward-thinking PlayStation future.

Vita’s Last Breath

By 2015, the writing was on the wall. Sony’s once-grand handheld was now surviving on scraps, and the corporate retreat became undeniable. Big-budget projects from first-party studios dried up entirely—no more Uncharted-sized showcases, no more promises of console-quality gaming on the go. What remained was a trickle of niche Japanese releases and indie titles keeping the lights on.

Then came the quiet burial of Vita TV, discontinued in February 2016 after barely making a dent outside Japan. By the time E3 rolled around a few months later, the Vita had become the ghost at Sony’s banquet. The company’s press conferences were dominated by thunderous PS4 blockbusters and the shiny promise of PlayStation VR, while the handheld that once stole headlines wasn’t even granted a passing mention. No trailers, no new partnerships, not even a token sizzle reel.

The pullback wasn’t just about games. One by one, services and features were quietly shut down. Apps like YouTube and Maps vanished, social integration was stripped away, and the messaging client was pulled. The Vita’s identity as a connected, multimedia device evaporated almost overnight. It was a brutal silence, louder than any bad news could have been.

In the West, Vita was fading fast. But in Japan, the story played out differently. Titles like Freedom Wars tapped into the hunting-action craze, offering a futuristic spin that kept local fans engaged. Late-arriving stand-ins like Soul Sacrifice and Toukiden were all solid games. Square Enix bolstered the catalog with Final Fantasy remasters, while Atlus, Falcom, and Compile Heart leaned into JRPGs that thrived on portability.

Then came a surprise hit: Minecraft. Mojang’s global phenomenon found a loyal audience on Vita, extending the handheld’s relevance far beyond expectations. Even without Capcom’s monster-slaying juggernaut, Japanese players embraced Vita as a JRPG machine, a visual novel library, and a quirky indie outlet.

When Nintendo unveiled the Switch, it felt like a curtain call for the Vita. Everything Sony had promised—a home console experience on the go, seamless transitions between living room and handheld play—Nintendo delivered with sharper execution and mass-market appeal. Within months, the Vita quietly fading into obscurity, while the Switch was exploding into a cultural phenomenon. Sony’s machine, once hailed as visionary, suddenly looked like a prototype for someone else’s triumph.

In 2019, Sony officially ceased production of the hardware, quietly announcing the end of an era with little fanfare. For loyal players, it was a gut punch, even if expected. The Vita had survived eight years, longer than most thought it would, but its death was defined by neglect rather than celebration.

Why Vita Failed

The Vita didn’t fall because of one mistake—it fell because everything that could go wrong, did. Sony’s decision to lock the system behind proprietary memory cards crippled adoption from day one, making entry costs far higher than rivals. But perhaps the most devastating blow came from losing Monster Hunter.

On PSP, Capcom’s monster-slaying series was nothing short of a cultural phenomenon in Japan—driving hardware sales into the tens of millions and creating a generation of gamers who bonded over ad-hoc hunts. Many assumed Vita would naturally inherit that audience. Instead, Capcom shocked the industry by shifting the franchise to Nintendo’s 3DS, beginning with Monster Hunter 3 Ultimate and then Monster Hunter 4.

The results were dramatic: in Japan, Monster Hunter 4 alone sold over 4 million copies and pushed the 3DS to heights Vita could never reach. Every new entry became a system-seller, anchoring Nintendo’s handheld dominance. Vita, by contrast, had to rely on late-arriving stand-ins like Soul Sacrifice, Toukiden, and Freedom Wars—all solid games, but none carried the cultural weight or mainstream draw of Monster Hunter. Without that one defining franchise, Vita never established itself as a “must-own” console in Japan, its most important market for handhelds.

Meanwhile, inside Sony, priorities shifted. The PlayStation 4 became the golden child, soaking up resources, marketing, and developer attention while the Vita faded quietly into the background. And outside the console wars, the world itself was changing. Mobile gaming exploded, delivering convenience and affordability that no dedicated handheld could match.

The result was a perfect storm: brilliant hardware trapped by bad business decisions, missing killer apps, corporate neglect, and an industry moving in a different direction. For all its innovation, it was a product out of time—arriving too early for cloud gaming to carry it, too late to stand against mobile, and too under-supported to survive in the shadow of Nintendo’s handheld empire. The Vita wasn’t just beaten—it was abandoned.

Shuhei Yoshida, who retired in 2025, would later admit that Vita was loved but undermined by its own design and resource struggles:

“Well, there are multiple reasons why Vita didn’t work. It worked in a way. People loved playing games, especially indie games, on PS Vita. Several technical choices we as a company made weren’t good ones, one of which was the dedicated memory card. Sometimes the team made amazing prototypes that felt so good, but the back touch added additional cost to the hardware. We had to stop many projects from Vita because we didn’t have teams to make PS4 games otherwise.”

What lingered was a system still beloved by its loyal fanbase but abandoned by the very company that built it. The dream machine that had once been paraded as the future of handheld gaming was now left to fade into the background, a cult favorite rather than the cultural force Sony had envisioned.

Vita Means Life

For all its commercial woes, the Vita carved out a legacy that endures. It became the beating heart of indie gaming on console, a portable stage for titles like Spelunky and OlliOlli to shine. For JRPG fans, it was nothing short of a treasure chest and countless niche imports gave the handheld an identity no other platform could replicate.

And yet, that’s precisely why Vita endures as more than just a failure. To this day, it remains a beloved cult classic, remembered fondly by those who invested in it. In many ways, Vita represents Sony at its most daring—willing to experiment, to push handheld gaming into uncharted waters, and to chase ideas that were as flawed as they were fascinating.

When Sony stopped caring, the community didn’t. With one of the highest software attach rates in Sony’s history, players proved that when you invested in the system, you lived in it. That passion has outlasted the hardware itself, with modders and homebrew developers gave the Vita a vibrant second life that arguably outshone its official twilight years. Unlocking the system through custom firmware opened the floodgates—suddenly the Vita wasn’t just a handheld, it was a playground.

Fans created tools to overclock the hardware, patch games for smoother performance, and even restore features Sony had abandoned. Emulators turned the device into a portable archive of gaming history, running everything from SNES and Genesis to Dreamcast and PSP with surprising finesse. Indie developers bypassed official channels entirely, releasing experimental homebrew that kept the machine relevant long after Sony moved on.

The hardware itself was embraced, too. Memory card workarounds like SD2Vita let players ditch Sony’s overpriced storage, while modders upgraded batteries, swapped shells, and perfected “ultimate” Vita builds. What began as a failed commercial product has survived as a hacker’s haven and collector’s dream—proof that once a console finds its tribe, it never truly dies.

Vita owners didn’t just buy games—they devoured them. That passion has outlasted the hardware itself, keeping the Vita alive in fan communities, aftermarket mods, and dedicated collectors. It may have failed in the marketplace, but the Vita thrives in memory—as a machine that dared to dream big and found its truest success in the hands of those who never let it go.

Even if the Vita itself faded, its spirit didn’t. Remote Play on PS5, the PlayStation Portal, and the broader acceptance of hybrid gaming owe something to Sony’s handheld gamble. And while Nintendo’s Switch and Valve’s Steam Deck perfected the portable-console model, Vita’s bold experiments paved the way. And yet, that’s precisely why Vita endures as more than just a failure. To this day, it remains a beloved cult classic, remembered fondly by those who invested in it.

The PlayStation Vita wasn’t the handheld that saved Sony, nor the one that dethroned Nintendo. But it was beautiful in its ambition, stubborn in its innovation, and unforgettable to those who carried it in their pockets. A mistake, perhaps—but one worth remembering.