The late ‘90s were a battleground. Sega had fired the first shot with the Dreamcast, a sleek machine that pushed online gaming into the mainstream. Nintendo was doubling down on its colorful, family-friendly empire. And Microsoft? Lurking in the shadows, ready to enter the fray. Sony, fresh off the seismic success of the PlayStation, had no intention of surrendering its throne. The answer? A machine so ambitious, so technologically audacious, that it wouldn’t just define an era—it would sell over 155 million units and become the best-selling console of all time.

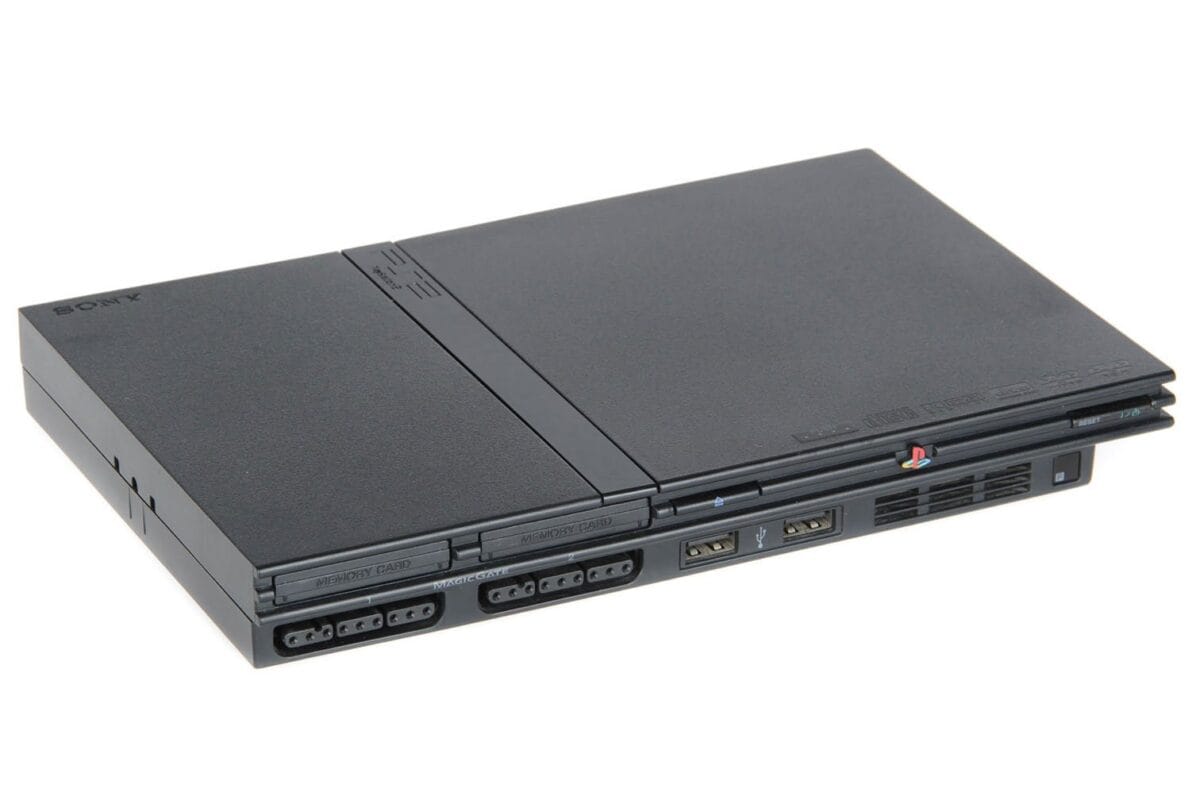

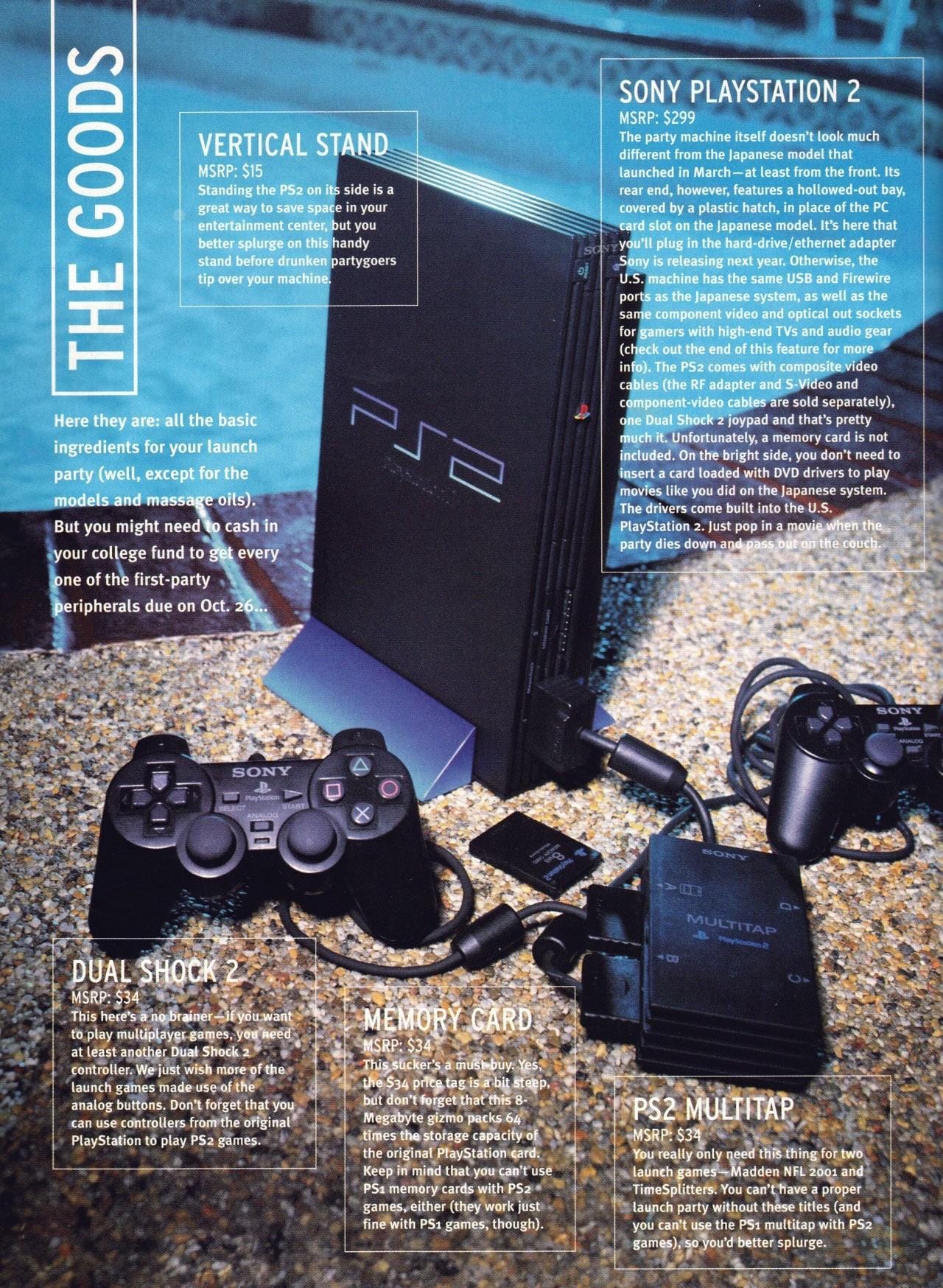

Enter the PlayStation 2. Announced in 1999, it promised a generational leap beyond anything gamers had seen. Backward compatibility, a built-in DVD player, and hardware so advanced that even military analysts took notice. It wasn’t just a console—it was a revolution in a black monolith. But success wasn’t guaranteed. With supply shortages, fierce competition, and a launch lineup that had to prove itself, Sony’s behemoth had everything to gain and everything to lose. This is the story of how the PS2 dominated the industry, reshaped home entertainment, and secured its place in gaming history.

Designing the PlayStation 2

Ken Kutaragi, the mastermind behind Sony’s gaming empire, didn’t just want to build a more powerful PlayStation—he wanted to redefine what a console could be. His vision wasn’t confined to gaming alone. Inspired by the rising importance of home entertainment, Kutaragi imagined the PlayStation 2 as a centerpiece for the entire living room. It wasn’t about kids playing games in their bedrooms anymore; it was about families gathering around a machine that could handle movies, music, and media with the same finesse as it played games. This shift in thinking planted the seeds for Sony’s future multimedia dominance.

Sony had just finalized its co-developed DVD-RW format with Philips—boasting an impressive 4.7GB of storage—and Kutaragi saw the potential immediately. Insisting that the PS2 should not only use DVDs for games but also double as a video DVD player, he clashed with Sony’s higher-ups. Many executives were still reeling from the PS1’s success cutting into standalone CD player sales and feared the same fate for their DVD hardware business. But with the personal backing of then-CEO Norio Ohga—who trusted Kutaragi’s instincts—the bold decision was made. That gamble paid off in spades.

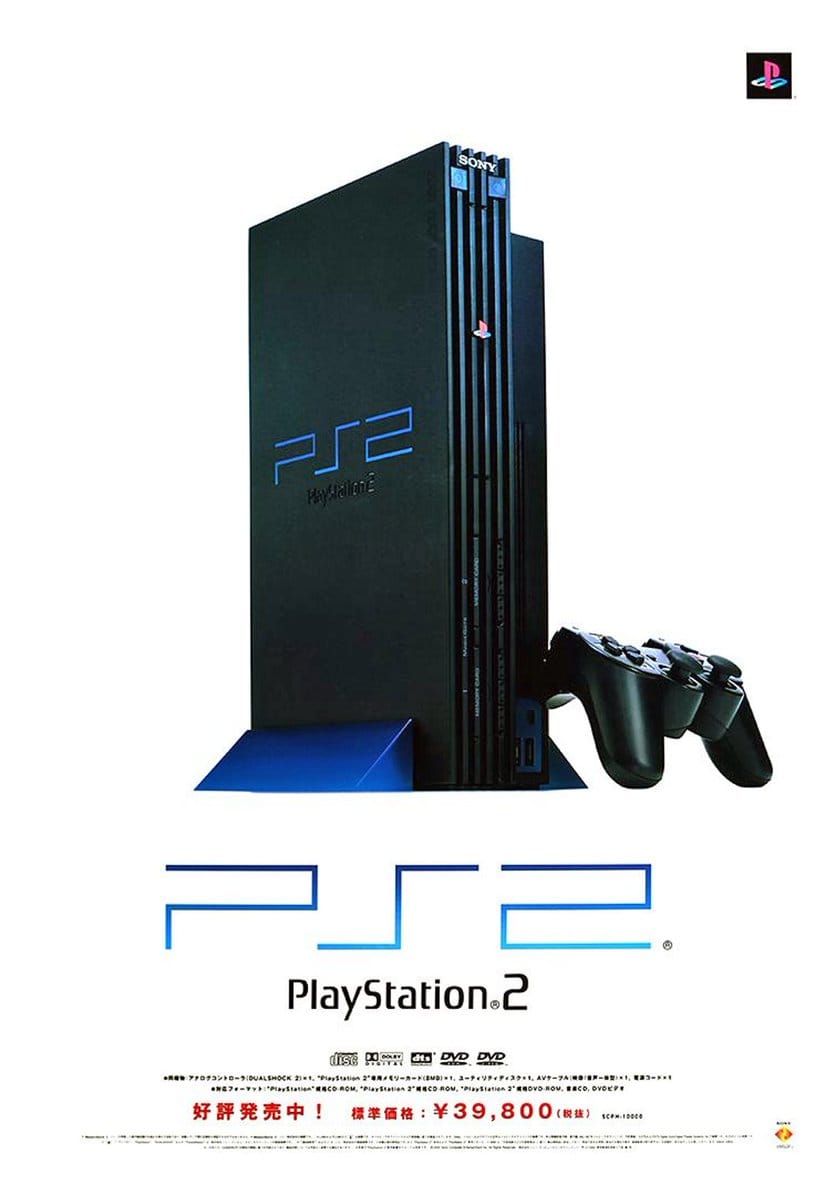

Teiyu Goto, the industrial designer behind the original PlayStation’s iconic look, returned to tackle its successor—but lightning didn’t strike twice at first. Early PS2 design concepts were met with disapproval from Sony’s leadership, largely because they bore an uncomfortable resemblance to the recently launched Sega Dreamcast. With competition heating up and image paramount, Sony knew it couldn’t afford to look like it was following Sega’s lead. Goto was back to square one, facing the challenge of designing something that not only looked next-gen but felt like a leap forward in identity and ambition.

Stuck in a creative rut, Goto turned to tech history for inspiration—and found it in an unlikely place: the Atari Falcon 030 MicroBox. Though it never made it to market, the Falcon’s sharp, angular form left a mark. Goto borrowed from its minimalism, then refined and reimagined it into something more commanding. The result was the PS2’s now-legendary vertical design—sleek, sharp-edged, and distinctly different from anything else on the market. It looked more like high-end audio-visual equipment than a toy, and that was exactly the point.

The visual identity of the PlayStation 2 wasn’t just about aesthetics—it was deeply symbolic. Goto chose a deep, matte black for the console’s casing, representing the universe itself: vast, infinite, and full of possibility. The bold blue logo was a stark contrast, meant to symbolize the Earth suspended in space—gaming as the center of a new digital universe. Together, they reflected Sony’s broader vision for the PS2: not just a step forward in gaming, but a leap into a new era of entertainment, emotion, and imagination.

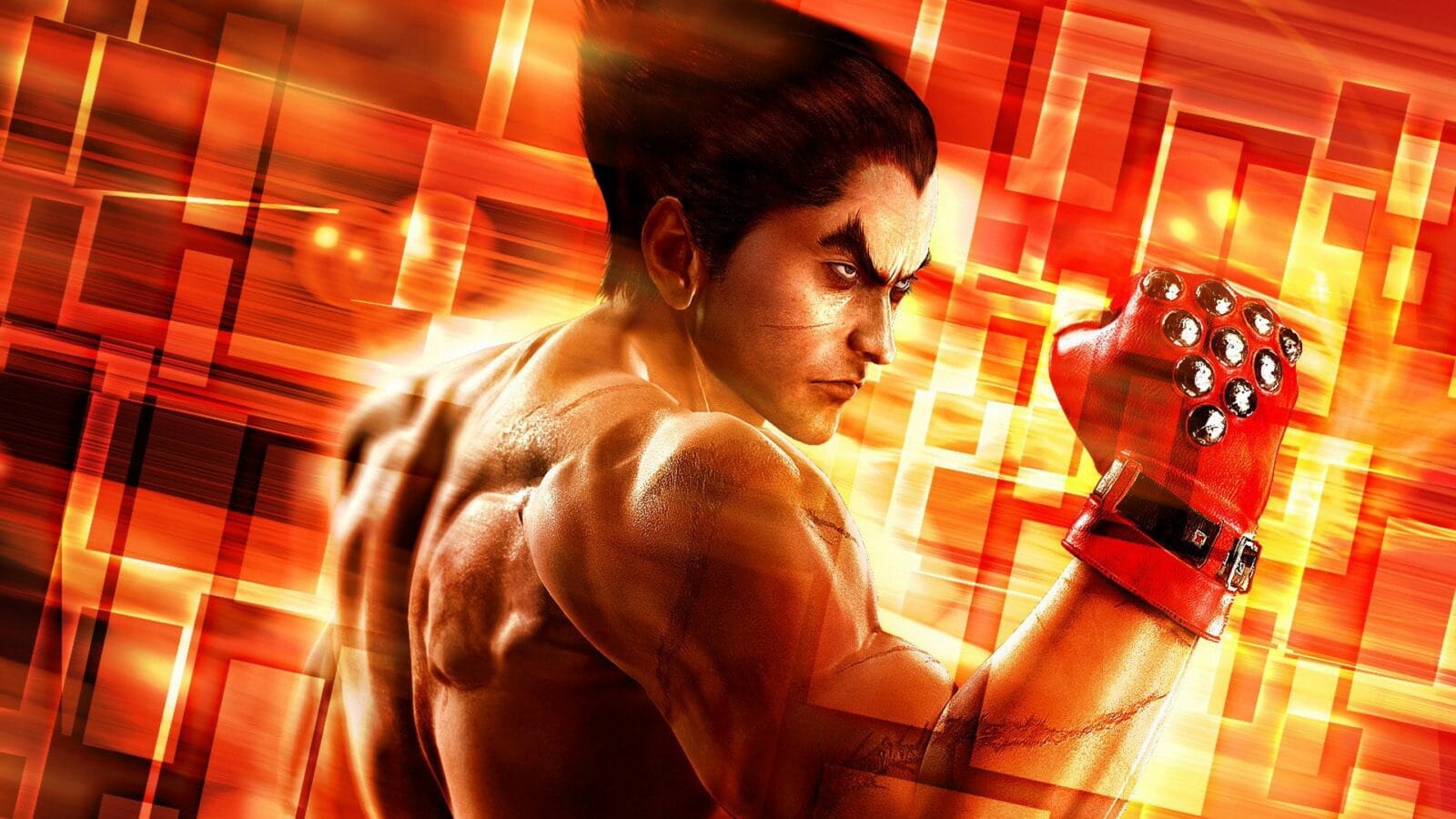

At the heart of the PlayStation 2 was a chip unlike anything else in the consumer market: the Emotion Engine. Co-developed with Toshiba, this custom processor boasted raw computational power that had analysts—and even government agencies—paying close attention. Its ability to perform complex floating-point calculations made it not just ideal for rendering advanced graphics, but also theoretically useful for simulations beyond gaming. Rumors swirled about export restrictions due to the chip’s military-grade potential. Whether myth or reality, the Emotion Engine gave the PS2 an air of mystique and unmatched technical swagger.

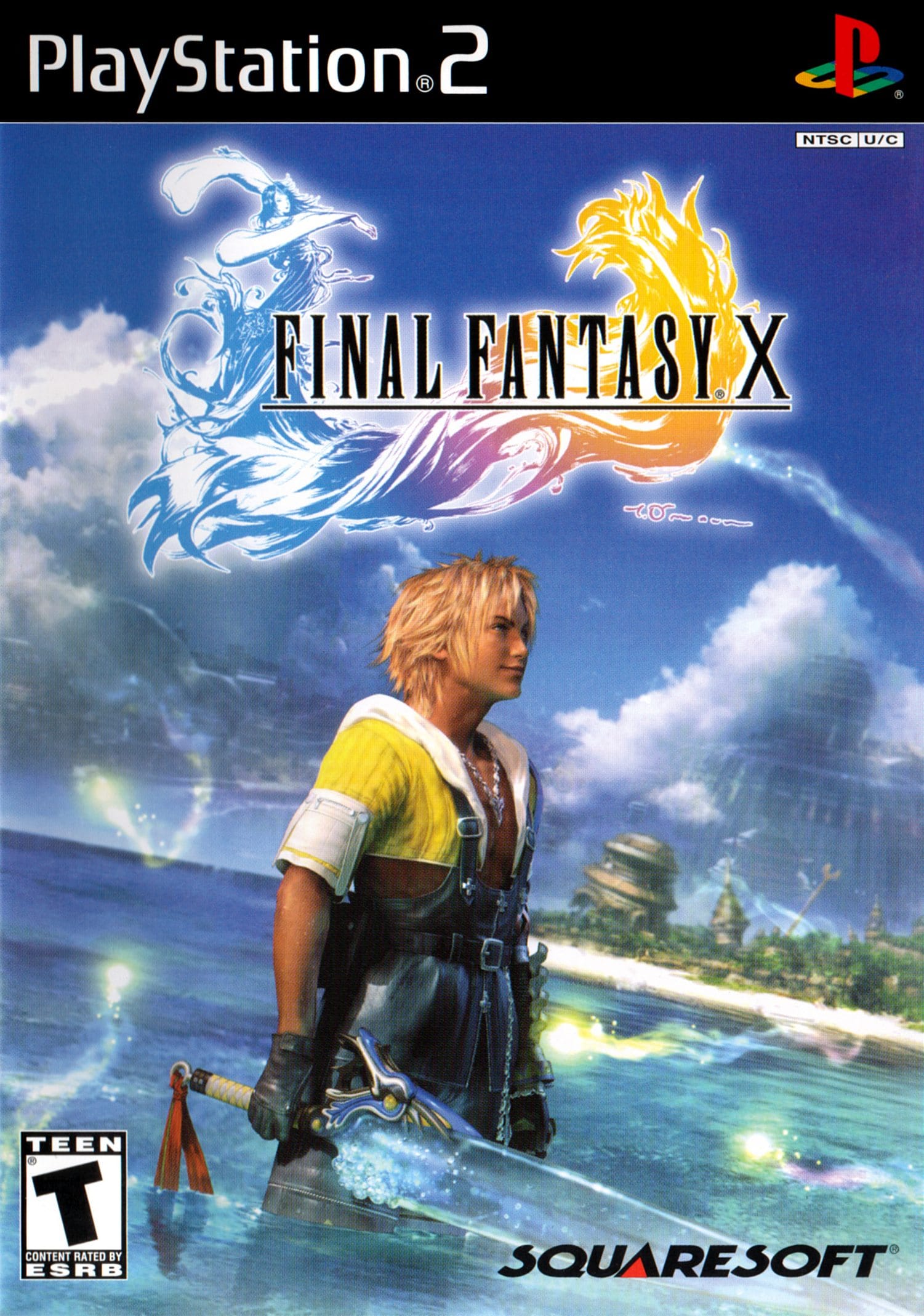

The name wasn’t just marketing flair—it was a statement of purpose. Sony believed that next-gen gaming wasn’t just about higher resolutions or smoother animations; it was about evoking genuine emotional responses. The Emotion Engine, they claimed, could simulate human expressions and nuanced movement in ways never seen before, bringing characters to life with cinematic intensity. It wasn’t just processing power—it was storytelling power. In an era where game narratives were growing bolder and more sophisticated, this focus on emotion helped define the PS2 as more than a machine—it was an artistic platform.

While the Emotion Engine got most of the attention, the PS2’s real-time rendering workhorse was the Graphics Synthesizer. With its insanely fast video memory and high fill-rate capabilities, it allowed developers to create rich, layered visuals that could rival pre-rendered CGI. It didn’t rely on conventional methods like texture compression or hardware shaders, which made it tricky to master—but in the right hands, it could produce stunning results. Games like Gran Turismo 3 and Okami pushed the chip to its limits, proving that this unsung hero was just as crucial to the PS2’s legacy as its more famous counterpart.

Excellent deep dive, I had the PS2 as a child and I definitely didn’t see the scope of it as I see it now, my first game was the “Peter Jackson’s King Kong: The Official Game of the Movie (2005)” and to be honest I am still amazed by its graphics alone!

Definitely the graphical jump from PS1 was abysmal (even as a kid I knew that).

King Kong’s graphics were incredible on the PS2! It was almost identical to the next-gen 360 version. The leap from PS1 to PS2 was like night and day compared to newer console generations.