In 2003, Nokia wasn’t just a brand—it was the brand. The undisputed titan of mobile phones, with a global footprint so vast it made Silicon Valley sweat. So when it announced the N-Gage—a hybrid device promising console-quality 3D gaming and mobile phone functionality—it sounded like the future. Why carry two gadgets when one could do it all?

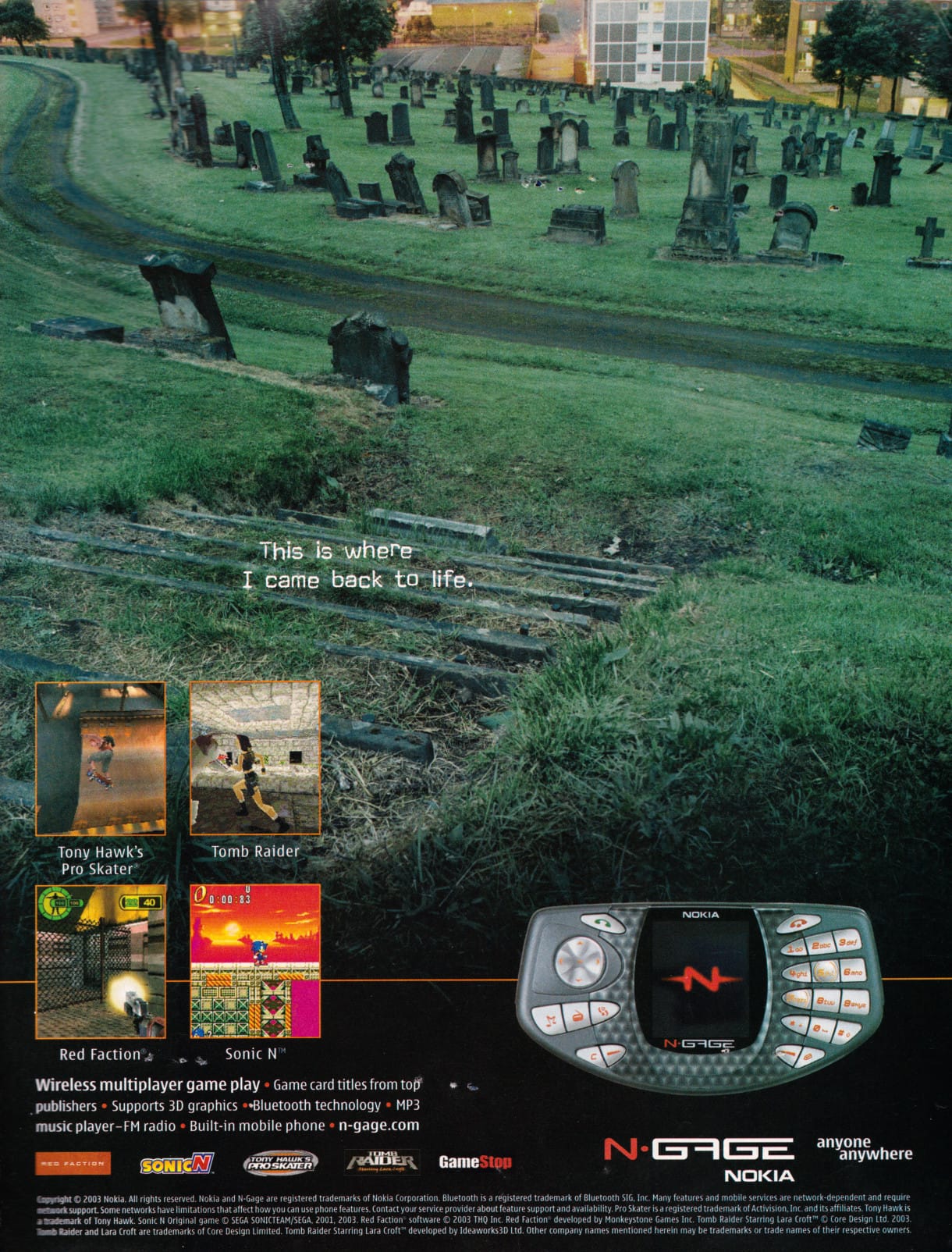

On paper, it was revolutionary. PS1-style graphics in your pocket. Full games like Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater and Tomb Raider—not watered-down ports, but nearly 1:1 conversions. And yes, you could call your mom in between kickflips. Compared to the 2 year old Game Boy Advance, it was a technological marvel.

But the promise soon soured.

Instead of a game-changer, the N-Gage became an object of ridicule. Poor ergonomics. Tedious cartridge swaps. A number pad masquerading as a controller. What should’ve been Nokia’s moment of glory turned into a cautionary tale of ambition outpacing execution. This is the story of how the company that ruled your pocket fumbled one of the boldest ideas in gaming history.

The Portable Gaming Warzone of the Early 2000s

In the early 2000s, Nintendo wasn’t just winning the handheld war—it had practically ended it before anyone else could show up. The Game Boy Advance, released in 2001, was an instant global success, moving millions of units within months. With a stacked launch lineup, near-infinite third-party support, and full backward compatibility with Game Boy and Game Boy Color titles, the GBA was the gold standard. Sure, it lacked flashy 3D visuals, but it made up for that with lightning-fast gameplay, iconic franchises, and a form factor that fit perfectly in your pocket.

Nintendo knew the audience. Knew the price point. Knew how to make games sing on limited hardware. Everyone else? They were just trying to keep up.

Enter Nokia. At the height of its power, the Finnish tech giant looked at the handheld space and saw a crack in the armor. Why settle for a dedicated gaming device when you could combine it with a mobile phone? The concept was electric—imagine playing full 3D games, then answering a call without switching devices. It was ambitious, disruptive, and totally uncharted territory.

In a market that had grown complacent, Nokia aimed to ignite a mobile revolution. But in a war ruled by fun and functionality, would innovation be enough to break Nintendo’s stranglehold?

Next-Gen on the Go: The N-Gage’s Technical Muscle

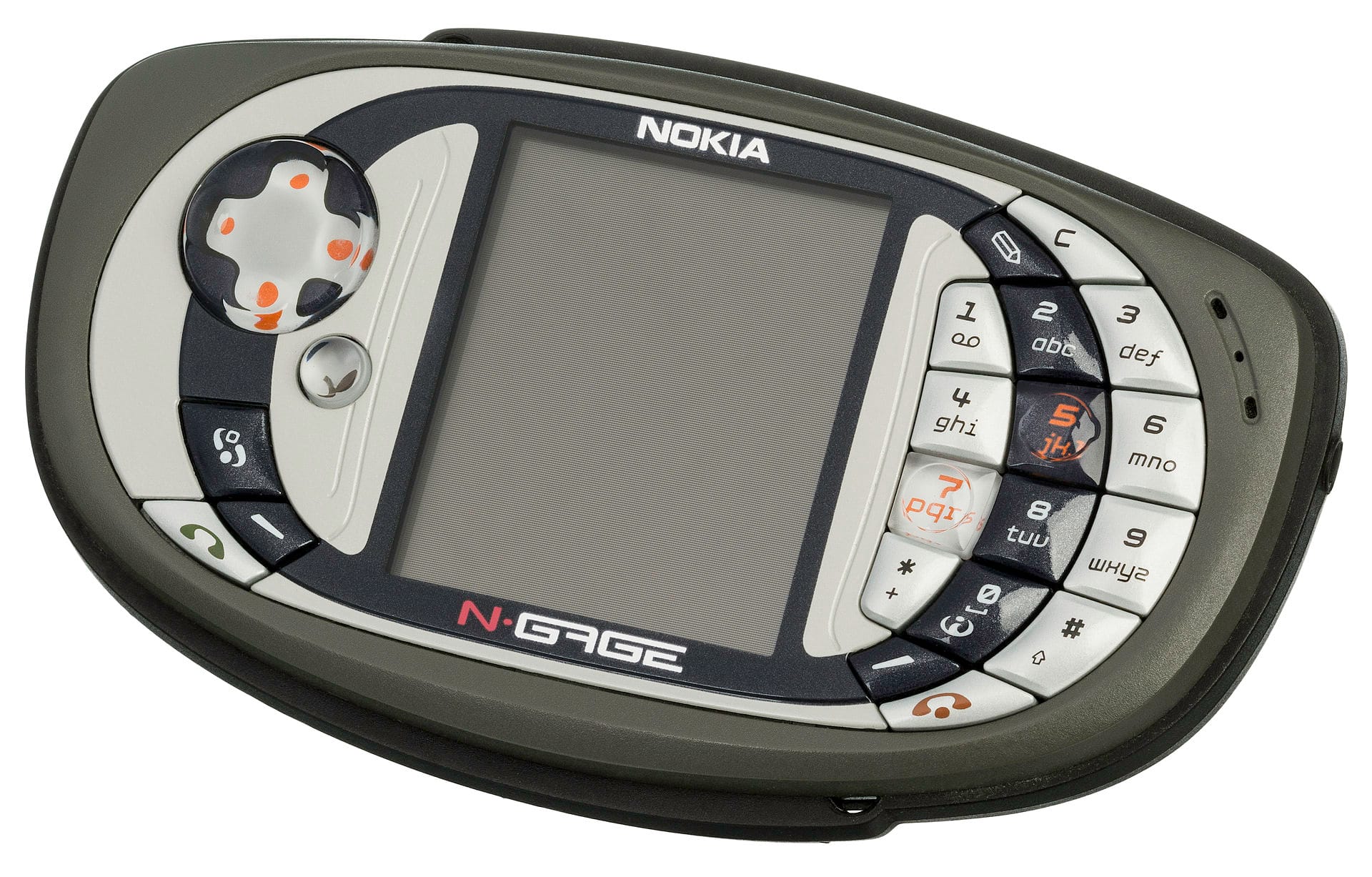

If there was one area where the N-Gage flexed hard, it was raw power. While the Game Boy Advance still leaned heavily on sprite-based visuals and Mode 7 tricks, the N-Gage came out swinging with full 3D rendering. Its ARM-based processor and custom graphics chip gave it horsepower that left the GBA looking like yesterday’s news. Characters weren’t just flat, they were polygonal. Environments weren’t faked—they were rendered in real time. Compared side-by-side, it was like watching a VHS tape battle a DVD.

Nokia made a bold statement with its launch lineup. Instead of handheld spin-offs, the N-Gage debuted with Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater and Tomb Raider—nearly identical to their original PlayStation counterparts. These weren’t reimagined versions with chibi characters or downgraded levels. These were full-featured, console-grade experiences you could take on the go. For a brief moment, it felt like the N-Gage was punching above its weight—and winning.

Beyond games, the N-Gage was a Swiss Army knife of tech. It played MP3s. It let you browse the web. It supported Bluetooth. And yes, it made phone calls—albeit with that now-infamous taco-shaped grip. In an era before the iPhone, this convergence of media, gaming, and communication was borderline science fiction. On specs alone, the N-Gage was the future. The question was whether users were ready to leap into it—or if they just wanted to play Pokémon in peace.

The Taco Phone: A Design That Doomed It

Even if you never held an N-Gage, you probably remember how it looked when someone used it. Side-talking became the stuff of internet legend. To make a phone call, users had to turn the device sideways and press it to the side of their face—like they were whispering into a taco. It wasn’t just awkward; it was unforgettable for all the wrong reasons. The moment tech blogs and late-night TV picked up on it, the N-Gage’s credibility took a nosedive. Memes spread faster than firmware updates, and the term “taco phone” was burned into history.

As a phone, the N-Gage looked unconventional. For a device aimed at mobile convenience, the N-Gage stumbled right out of the gate—literally. The N-Gage ran on Nokia’s Symbian platform—a powerful operating system for its time, but not one optimized for fast, fluid gaming. You didn’t just turn it on and jump into your game; you had to wait for the Symbian OS to load, sit through logos, and then navigate to the game itself. Want to sneak in a quick session before class or on a coffee break? Forget it. By the time your game was ready, your moment was gone. Compared to the GBA’s instant-on, cartridge-to-game simplicity, the N-Gage made even basic tasks feel like digital molasses.

As a gaming device, it was a usability disaster. Where are the shoulder buttons? Even the Game Boy Advance, which was no good example of control options, had shoulder buttons. The N-Gage? Not a trace. In trying to maintain a phone-first footprint, Nokia left out one of the most critical inputs for action-heavy titles. For genres like racing, shooters, or fighters—shoulder buttons weren’t just helpful, they were essential. Without them, core gameplay suffered, forcing developers to make compromises that only further exposed the device’s clunky limitations.

Imagine being deep into a gaming session and wanting to switch titles. On most handhelds, it’s a two-second task. On the N-Gage? It was a full-blown ritual. First, you had to power the device down. Then, remove the backplate. After that, take out the battery—yes, the battery—just to access the game card slot underneath. Once you swapped the game, you had to reinsert the battery, slap the backplate back on, and boot the whole system up again. That wasn’t just clunky. That was anti-fun.

Meanwhile, over in Nintendo land, the Game Boy Advance let you hot-swap cartridges in seconds. No power down, no screwdrivers, no stress. This contrast was brutal. Where the GBA made switching games seamless, the N-Gage turned it into a chore—an experience so poorly thought out it bordered on parody. For players looking for quick play sessions or multiplayer swaps, Nokia’s design made the process feel like punishment. And in the portable gaming world, convenience isn’t optional—it’s everything.

The N-Gage didn’t just lack good controls—it lacked consistent ones. With no dedicated action buttons and a number pad doing most of the heavy lifting, every game developer was forced to improvise. One title might use “5” to jump, another might map it to “7,” and some relied on multi-button combos that felt more like texting than gaming. There was no universal layout, no intuitive logic. Just a patchwork of clumsy design choices that turned even the most straightforward gameplay into a guessing game.

In the golden age of pick-up-and-play, the N-Gage practically dared you to try playing blind. Forget muscle memory—without a manual in hand, good luck figuring out how to shoot, run, or even pause. Some games came with fold-out control diagrams, which felt more like flight sim instructions than portable fun. This wasn’t just an oversight—it was a full-blown user experience breakdown. Where Nintendo streamlined interaction to make games accessible to anyone, Nokia left players fumbling for buttons and flipping through booklets. The result? Frustration before the fun even started.

In a device made by the biggest phone manufacturer on the planet, you’d expect volume control to be a no-brainer. Yet the N-Gage shipped without dedicated volume buttons—a baffling omission. Adjusting the sound meant navigating into the system menu or diving into in-game settings, assuming the game even had them. Want to lower the volume mid-match? Too bad. You had to break immersion, stop everything, and tinker with menus like you were configuring a fax machine. It was clunky, slow, and totally unacceptable for a handheld gaming device in 2003.

Public gaming on the N-Gage felt like a social experiment in embarrassment. Between the side-talking call position, the speaker blasting at full volume, and no quick way to silence the device, it was a recipe for awkward stares. Playing Tomb Raider in a coffee shop? Better hope no one minds the gunfire and grunts. Even simple things like riding the bus while gaming became a cringe-worthy ordeal. A basic feature—volume control—should never be the reason a device feels unusable in public, but on the N-Gage, it absolutely was.

N-Gage Arena: Ahead of Its Time, but Too Expensive

Before Xbox Live became the gold standard and before Wi-Fi was standard in handhelds, Nokia launched N-Gage Arena—a bold, cloud-reaching attempt to bring online multiplayer and community features to the portable gaming world. Players could upload high scores, download ghost data, and even engage in direct online matches. In concept, it was visionary. A handheld that let you battle someone across the world while sitting in a café? In 2003, that sounded like science fiction made real.

The magic faded the moment you looked at your phone bill. Using N-Gage Arena meant relying on GPRS data—slow, spotty, and expensive. In an era where unlimited data plans were rare and text messages cost money, online multiplayer on a phone was more financial burden than breakthrough. The idea was cool, but the infrastructure and pricing weren’t ready. For most players, it simply wasn’t worth the hit to their wallets just to play Tony Hawk Pro Skater online.

Oddly enough, Nokia never leaned into local wireless play—something even the Game Boy had embraced with link cables. With Bluetooth built in, the N-Gage had the hardware to support ad-hoc multiplayer, but it was rarely used effectively. If Nokia had prioritized simple, local experiences instead of jumping straight into the deep end of online gaming, the N-Gage might’ve fostered the kind of in-person fun that made other handhelds beloved. Instead, it bet on the future and left the present behind.

An Ambitious Library That Lacked Identity

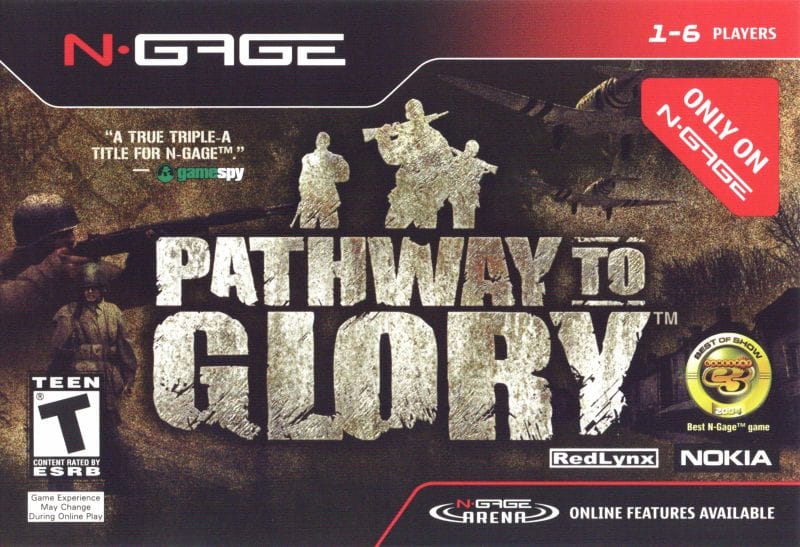

Nokia didn’t just want flashy ports—it wanted exclusives. And to its credit, it got them. Titles like ONE (a gritty 3D fighter), High Seize (a turn-based strategy game with a naval twist), and Pathway to Glory (a tactical WWII shooter) weren’t lazy throw-ins. They were polished, ambitious, and genuinely impressive for a mobile platform in the mid-2000s. But there was one problem: they felt familiar. ONE looked like a budget Tekken. High Seize was Advance Wars with boats. Pathway to Glory played like a diet version of Commandos. They weren’t bad games—they were just echoes of better-known titles.

For a platform already saddled with odd controls and design quirks, relying on knockoff versions of beloved franchises only amplified its weaknesses. Playing a strategy game with a number pad or a fighter without shoulder buttons felt awkward at best, unplayable at worst. These genres needed precision, standardization, and comfort—three things the N-Gage rarely delivered. Instead of carving its own identity through creative, mobile-first design, the N-Gage library tried to replicate console experiences on hardware that wasn’t suited for them. In the end, it was a collection of games that wanted to be something else—on a system that didn’t know what it wanted to be either.

The N-Gage Had Nowhere Left to Go

In 2004, Sony dropped a bombshell—the PlayStation Portable. Sleek, powerful, and bursting with graphical fidelity, the PSP was everything the N-Gage wanted to be but couldn’t. With a massive widescreen display, proper analog controls, and a UI that didn’t require a learning curve, Sony’s handheld looked—and played—like the future. It wasn’t just a gaming device; it was a full-blown multimedia powerhouse. You could watch movies, listen to music, browse the web, and play games that looked like PS2-lite titles. For the hardcore gaming audience, the PSP made the N-Gage feel like a tech demo from a bygone era.

Then came Nintendo’s counterpunch—the Nintendo DS. Dual screens, touch controls, a built-in mic, PictoChat, and that all-important backward compatibility with the GBA library. It was quirky, accessible, and instantly lovable. More importantly, it came with Nintendo’s stamp of quality and a steady stream of must-play games: Mario Kart DS, Nintendogs, Brain Age, Animal Crossing: Wild World. It catered to everyone—from casual newcomers to seasoned players—and redefined what handheld gaming could be.

With the PSP dominating the tech-savvy crowd and the DS devouring the mainstream, the N-Gage found itself stranded in no man’s land. It was neither powerful enough to go toe-to-toe with Sony, nor user-friendly enough to compete with Nintendo. Its few remaining strengths—online connectivity, multimedia features—were quickly outclassed. And without a killer app, strong brand loyalty, or a compelling user experience, the N-Gage simply faded into the noise.

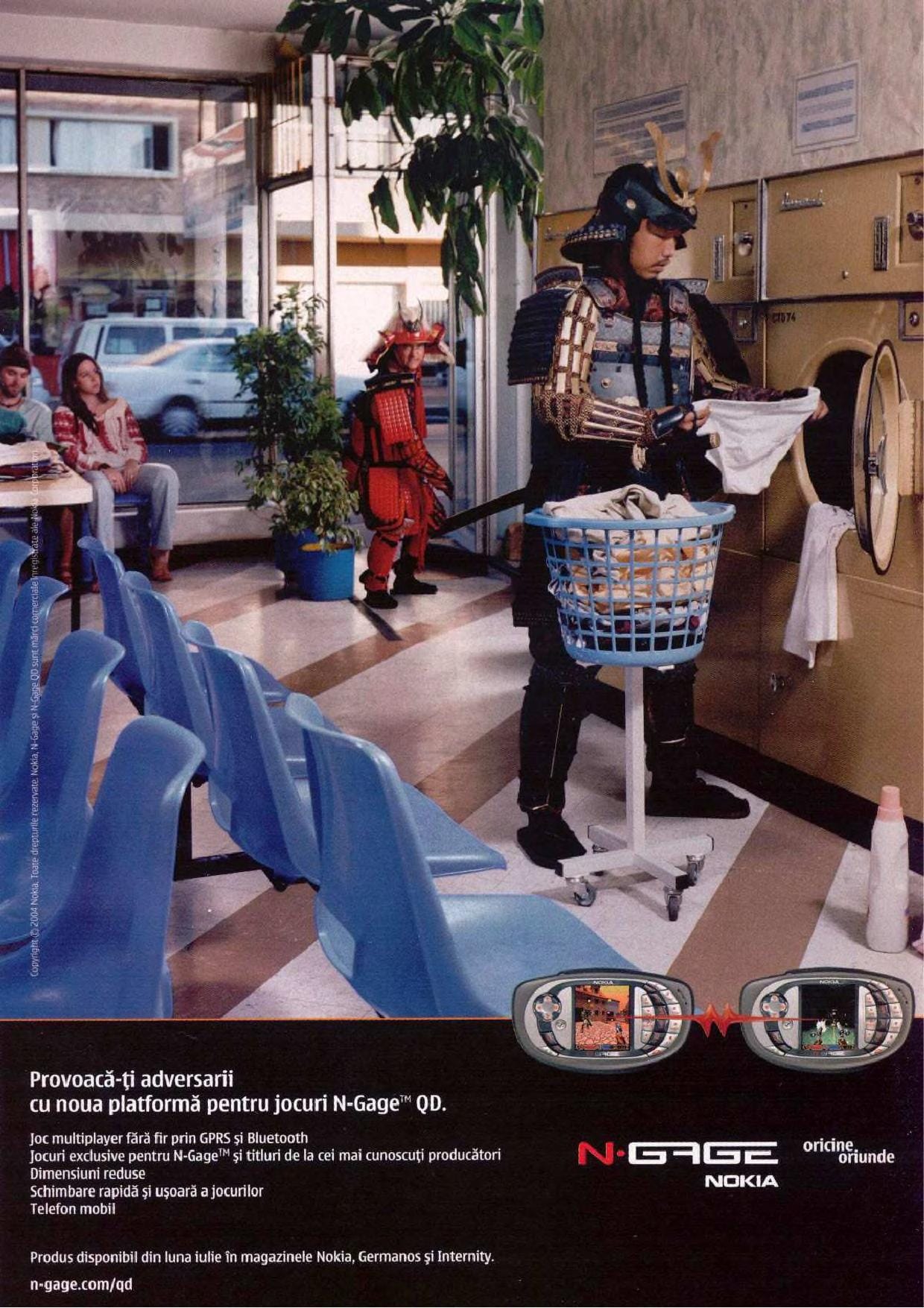

The N-Gage QD: Too Little, Too Late

Just a year after the N-Gage’s rocky debut, Nokia returned with a second swing: the N-Gage QD. This wasn’t a sequel—it was an apology. Gone was the side-talking embarrassment, replaced with a more sensible microphone placement. The new model also boasted better battery life, a more compact form factor, and slightly improved durability. Most importantly, Nokia addressed the single most ridiculous flaw: you could finally swap game cartridges without removing the battery. It was progress—but it felt like patchwork on a sinking ship.

While the QD solved a few of the original’s biggest issues, it created a few new ones in the process. The improved cartridge slot was placed on the bottom of the device and covered by a rubber flap that felt awkward and flimsy. The number pad was still clunky, the screen was even smaller than before, and Nokia completely removed MP3 and USB support—features that actually gave the original N-Gage some multimedia clout. In trying to simplify the device, Nokia stripped away what little identity it had left. The QD wasn’t a reinvention. It was a bandaid. And by the time it launched, the world had already moved on.

Sales, Reputation, and Discontinuation

Despite Nokia’s massive marketing push and deep pockets, the N-Gage never took off. Initial sales were dismal—estimates suggest only around 3 million units were sold across all models, a drop in the ocean compared to the Game Boy Advance’s 81 million and the PSP’s explosive early numbers. By 2006, Nokia quietly pulled the plug on the hardware line, never releasing a true successor. What was once marketed as a revolution in mobile gaming had become a cautionary tale in product design. Retailers slashed prices, game releases dried up, and support slowly vanished. It wasn’t just a flop—it was an industry punchline.

Perhaps the most telling failure was the N-Gage’s inability to win over tech lovers—the very audience who should’ve embraced it. It had bleeding-edge specs, hybrid functionality, and a vision of convergence long before the iPhone. But the execution was so compromised—between its clunky controls, baffling UI, poor ergonomics, and inconsistent game library—that even early adopters tapped out. You couldn’t tinker with it. You couldn’t enjoy it casually. And for all its power, it never felt good to use. Enthusiasts didn’t just abandon it—they disowned it. And once that crowd walks away, there’s no lifeline left.

N-Gage’s Second Life: From Device to Download Service

After pulling the plug on the N-Gage hardware, Nokia wasn’t quite ready to abandon its gaming ambitions. In 2008, it attempted a soft reboot—not with a new device, but with a digital distribution platform called the N-Gage service. Instead of selling cartridges, Nokia embedded the service into high-end feature phones, allowing users to download games directly to their devices. It was sleek, built-in, and no longer tied to the awkward taco-shaped hardware. Classic N-Gage titles like Pathway to Glory and System Rush got a second wind, now accessible through a cleaner, app-like experience.

The strategy was clever. The execution? Better. But the timing? Brutal. In 2007, Apple unveiled the iPhone—and with it, a seismic shift in how people interacted with technology. When the App Store launched a year later, it democratized game distribution overnight. No more clunky platforms, no locked-in ecosystems, no overpriced hardware just to play a few decent games. Suddenly, developers could reach millions with a tap, and users could download polished, addictive titles instantly. Games were now part of a broader, smoother mobile experience—fluid, intuitive, and frictionless.

For Nokia’s N-Gage service, it was a death sentence. Touchscreens, intuitive interfaces, and an ever-growing ocean of casual games made the N-Gage service feel dated before it had a chance to thrive. By the time Nokia officially shut down the service in 2009, the mobile gaming market had evolved into something the company helped predict—but couldn’t capitalize on. Once again, Nokia was early, but not right.

Their vision of downloadable mobile games had promise, but Apple made it effortless. Nokia’s curated catalog, buried in Symbian menus and tethered to feature phones, couldn’t compete with the tidal wave of innovation unleashed by iOS.

By the end of 2009, Nokia quietly pulled the plug on the N-Gage service. No press conference. No fanfare. Just a support page and a sunset date. It was a quiet end to a bold, often misunderstood initiative—a final admission that the market had moved on without them. What began as a radical idea to merge gaming and mobile technology ultimately became a case study in how quickly innovation can be outpaced when execution falters and timing misfires.

What the N-Gage Got Right

Say what you will about the N-Gage’s design misfires, but in terms of raw ambition, it was leagues ahead. In 2003, handheld 3D gaming was almost nonexistent. The Game Boy Advance faked perspective with Mode 7 effects, and most mobile games were still stuck in 2D sprite land. The N-Gage delivered real, fully-rendered 3D environments on a portable screen—bringing console-style gaming to your pocket years before the PSP or Nintendo DS would do it at scale. Titles like Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater and Tomb Raider weren’t watered-down—they were full-fledged experiences. And that graphical muscle? Legitimately impressive for the era.

Long before smartphones became everyone’s main gaming device, the N-Gage asked a simple question: Why carry two gadgets when one can do both? It was a phone. It was a game console. It could play MP3s, browse the web, and connect online. In 2003, that kind of convergence was practically science fiction. It anticipated the modern smartphone years before the hardware and infrastructure were ready to support it. As clunky as the execution was, the idea itself was visionary.

The N-Gage laid the groundwork—clumsily, yes—but undeniably. It envisioned downloadable games before app stores. It experimented with wireless multiplayer before Wi-Fi handhelds were a thing. It pushed mobile graphics when everyone else was chasing pixel art. Features like in-game voice chat, online leaderboards, and cloud saves—today’s standard—were all flirted with on N-Gage Arena. Though it failed to find an audience, the N-Gage helped plant the seeds for what mobile gaming would eventually become. It may have flopped, but it didn’t fall flat without leaving a footprint.

What the N-Gage Got Wrong

The N-Gage had bold ideas—hybrid functionality, 3D graphics, digital connectivity—but none of it mattered when the fundamentals were broken. In chasing the future, Nokia overlooked the present. Simple tasks like swapping a game or adjusting volume were convoluted. Navigation was unintuitive. Boot times were glacial. Instead of designing around how players actually use handhelds, Nokia built a device that asked users to adapt to it. The result? A machine that looked advanced but played like a prototype.

From the moment you picked it up, the N-Gage felt like it was working against you. The cramped screen, poorly placed d-pad, and number-pad-as-buttons setup made gameplay awkward and physically tiring. No shoulder buttons meant genre limitations. No volume rocker meant constant menu-diving. Even calling someone looked ridiculous thanks to the infamous “side-talking” posture. It wasn’t just flawed—it was frustrating. The device punished spontaneity and made every action feel like effort.

Was the N-Gage for gamers? Tech-heads? Mobile users? Nokia never really decided. Hardcore gamers were already eyeing the upcoming PSP. Casual players flocked to the simplicity and charm of the Game Boy Advance and, later, the Nintendo DS. Tech enthusiasts expected polish and practicality. The N-Gage tried to appeal to everyone and satisfied no one. Without a clear identity or dedicated demographic, it became a product without a purpose—outgunned, outclassed, and ultimately, out of the game.

Conclusion

Time has a funny way of softening failure. What was once mocked is now mythologized. The N-Gage, once a punchline, has found a second life as a cult curiosity. Retro collectors seek it out for its rarity and weirdness. Hardcore enthusiasts celebrate its boldness, its ahead-of-the-curve ideas, and its niche but surprisingly playable library. Devices in good condition fetch respectable prices online, and games like Pathway to Glory or System Rush are now viewed through a nostalgic lens. It’s not just about playing the games—it’s about owning a piece of gaming’s strangest “what if” story.

At a time when Nokia could seemingly do no wrong, the N-Gage was a rare misfire—an ambitious leap without a proper landing. It had the brand power, the budget, and the technology to shake up the gaming world. But instead of refining the essentials, Nokia overloaded the N-Gage with ideas that looked good on a spec sheet but fell apart in real-world use. From the disastrous design choices to the muddled messaging, it was a classic case of too much, too soon—and not enough of what actually mattered.

And yet, there’s something undeniably captivating about the N-Gage. It dreamed big. It saw a future no one else did and tried to get there before anyone else even started running. It fused gaming and mobility long before the iPhone made it effortless. It embraced online features before they were industry standard. In many ways, the N-Gage was a prophet in the wrong era—visionary, but ultimately undone by its own ambition. A console too smart for its own good, left behind by a world that just wasn’t ready for it.