The Nintendo 64 arrived with the weight of the world—and a mushroom kingdom—on its shoulders. It was bold, unconventional, and unmistakably Nintendo. Promising 64-bit power, revolutionary 3D gameplay, and a controller unlike anything we’d ever seen, the N64 set out to redefine the way we played video games. And in many ways, it did.

But behind the landmark titles and industry-shaping innovations, the N64 also stumbled. It alienated key developers, lagged behind in third-party support, and stuck with costly cartridges while rivals embraced the future with CD-ROMs. The PlayStation took the market by storm, while the Saturn found its niche—leaving Nintendo’s powerhouse oddly isolated.

So, how do we judge it? Was the Nintendo 64 a glorious experiment that shaped the modern gaming landscape—or a misstep that cost Nintendo its dominance? Let’s dig into the history, the highs, the heartbreaks, and the legacy of one of gaming’s most fascinating consoles.

The Console Wars of the Early ’90s

The early ’90s were less a playground, more a war zone. Not for politicians or philosophers—but for pixel-slinging titans armed with slogans and silicon. In one corner: the SNES, elegant and deliberate, a symphony of sprites and polish. In the other: Sega’s Genesis, brash, bristling with “Blast Processing” and the swagger of a Saturday morning cartoon. It wasn’t just a hardware showdown—it was culture versus counterculture.

Parents debated purchases. Schoolyards became battlegrounds. The SNES dazzled with Mode 7 and an ever-expanding library of hits. But the Genesis, with its edgy ads and faster ports, carved deep into Nintendo’s dominance, finishing a strong second—and with momentum.

Wounded but not defeated, Nintendo didn’t retreat. Instead, it began scheming. Not for another incremental upgrade, but for something radical. Something defiant. Behind closed doors, under codenames and corporate whispers, a project was born—one that would redraw the console blueprint and plunge headfirst into the uncharted realm of 3D. Before long, the world would know its name. But first, there was betrayal. There was ambition. And there was Sony.

Behind Closed Doors: Building the “Nintendo PlayStation”

As the 16-bit era marched on, Nintendo began quietly working on a bold expansion for its blockbuster Super Famicom—a CD-ROM add-on that would allow for bigger games, full-motion video, and new kinds of interactive experiences. To make it happen, they reached out to an unlikely ally: Sony. At the time, Sony was a titan of consumer electronics, riding high on the success of the Walkman and Trinitron. For Nintendo, they weren’t just picking a tech partner—they were inviting a juggernaut into the temple.

The plan was to create the “Play Station”—a hybrid console that combined Super Famicom hardware with a CD drive developed by Sony. Internally, it was a technological dream: enhanced sound, massive storage, and a chance to stay ahead of the curve as Sega made overtures toward disc-based gaming with the Sega CD.

Prototype units were developed. Engineers from both companies worked together to forge the future. Sony’s ambitions quietly grew. Not content with just powering Nintendo’s peripheral, they wanted to include their own CD-based format alongside Nintendo’s cartridges—a strategic foot in the door of the gaming industry. Nintendo, always fiercely protective of its licensing ecosystem, started to feel uneasy.

The tension simmered in the background, but both sides kept up appearances. Prototypes were shown in secret. The hybrid “Play Station” was real—playable, even. But as Sony began making plans to assert more control over the format, Nintendo’s leadership started plotting an escape route.

Then came the public bombshell. At the 1991 Consumer Electronics Show, Sony took the stage expecting to announce its official partnership with Nintendo. But the next morning, Nintendo delivered a shocking keynote—publicly announcing it had instead partnered with Philips to develop its CD-ROM strategy. No memo. No prior warning. Just a slap across the face delivered under the glare of Vegas stage lights.

Sony was blindsided. Furious. Humiliated.

Rather than abandon gaming, they turned betrayal into motivation. Within days, Sony executives gave their gaming engineers a new directive: finish what they started. Only now, they’d do it without Nintendo—and on their own terms. That fateful moment laid the foundation for the original PlayStation, and ultimately, one of the greatest console rivalries in gaming history.

Teaming Up with Silicon Graphics

After the Sony fiasco, Nintendo needed a bold new direction—and fast. Enter Hiroshi Yamauchi, the hard-nosed, no-nonsense president of Nintendo, who wasn’t interested in licking wounds. Instead, he set his sights on something revolutionary. In August 1993, at Nintendo’s Shoshinkai trade show, Yamauchi announced a partnership with Silicon Graphics Inc. (SGI)—a company best known for powering Hollywood blockbusters like Terminator 2 and Jurassic Park.

SGI had cutting-edge 3D tech, and Nintendo had the platform to bring it to living rooms worldwide. Together, they would design a 64-bit console that could deliver arcade-quality visuals at a consumer-friendly price. The partnership was bold, unexpected—and a total curveball for an industry still leaning heavily on 2D sprite work and CD-based cutscenes.

Yamauchi promised that the upcoming console would cost under $250—cheaper than most disc-based competitors and boasting double the processing power. This was a seismic promise in 1993. Where Sega and Sony were angling toward CD-ROM and 32-bit processing, Nintendo was essentially saying: “Forget all that. We’re skipping a generation.”

The system, codenamed “Project Reality,” would leapfrog the present and head straight into the future. It would offer real-time 3D rendering, powerful anti-aliasing, and visual fidelity never seen before in a home console. It wasn’t just a system; it was Nintendo throwing down the gauntlet.

Even the name—Project Reality—felt like something out of a sci-fi film. It wasn’t flashy, but it had weight. It implied that what you were seeing on screen wasn’t just pre-rendered smoke and mirrors—it was happening live, in real time, right in your living room.

At a time when most gamers were still marveling at Mode 7 and faux-3D effects, Project Reality promised fully explorable 3D worlds with true polygonal characters and environments. It was a radical reimagining of what console gaming could be, built from the ground up for immersive, interactive 3D experiences.

The future had a name. And Nintendo was ready to claim it.

CDs vs. Cartridges: Nintendo Bets Against the Industry

As Sony and Sega embraced CD-ROM technology with open arms, Nintendo made a decision that baffled much of the industry—they stuck with cartridges. To many, it felt like clinging to the past while the rest of gaming charged into the future. But Nintendo had its reasons.

In interviews at the time, Nintendo argued that CDs were too slow. Loading times, they claimed, would ruin the immersive nature of gameplay. Cartridges, on the other hand, offered near-instant data access. They were durable, harder to pirate, and had a legacy of stability. In the eyes of Nintendo’s leadership, faster and more reliable trumped spacious and cheaper. But this move, made with technical control in mind, would end up costing them dearly.

From a hardware perspective, Nintendo wasn’t entirely wrong. Cartridges did offer faster load times and better anti-piracy protection. But they came with glaring drawbacks: they were significantly more expensive to manufacture and held a fraction of the data a CD could store. While a PlayStation CD could house upwards of 650MB, Nintendo’s cartridges topped out at around 64MB—and most games used much less.

This limitation wasn’t just a number on paper. It shaped how games were made. Developers had to compress audio, cut content, and abandon full-motion video. Ambitious projects had to be scaled down or canceled altogether. While Nintendo believed gamers would care more about performance than cutscenes or voice acting, developers and publishers felt the squeeze.

The Big Rebrand: From Project Reality to Ultra 64

With Project Reality taking shape, Nintendo decided it was time for a name that sounded, well, cooler. In 1994, the console was reintroduced to the world as the Ultra 64. The name leaned hard into power and performance—it conjured images of sleek, futuristic hardware with unprecedented capabilities. Arcades even got a taste early, as Killer Instinct and Cruis’n USA were marketed as being “powered by Ultra 64.”

Nintendo began hyping the system as a generational leap—something that would make the 32-bit Sega Saturn and Sony PlayStation look outdated on arrival. And for a while, the hype machine worked. The Ultra 64 was mysterious, powerful, and dripping with promise. But then came the delays.

By the time the first-ever E3 rolled around in 1995, fans and press were expecting the Ultra 64 to finally be ready for prime time. After all, Sony and Sega had already launched their next-gen systems in Japan, and the U.S. rollouts were well underway.

Nintendo did show up—with flashy tech demos, concept art, and confident promises. But then came the gut punch: the Ultra 64 was delayed until 1996. Despite just recently completing the console’s hardware design, Nintendo insisted the extra time was needed to ensure developers could deliver true next-gen experiences. Gamers weren’t thrilled. Retailers weren’t thrilled. Even some developers were caught off guard.

The delay wasn’t just a missed deadline—it gave the PlayStation and Saturn a massive head start. And it exposed deeper issues under the hood.

Developing for the Ultra 64 was no walk in the park. Unlike the relatively straightforward SNES, the new system was built around high-performance 3D architecture from Silicon Graphics—a setup that introduced a steep learning curve, even for seasoned developers.

To make matters worse, the development kits shipped in English, posing a major challenge for Japanese studios. The jump to 3D design wasn’t just a tech upgrade; it was a full-blown philosophical shift. Developers had to rethink everything—movement, camera angles, animation, level design. And without tools that felt intuitive or documentation that made sense to non-English speakers, progress was slow.

The result? Many studios couldn’t hit Nintendo’s internal deadlines. Some dropped out entirely. What was meant to be a technological marvel started to look like a logistical nightmare. And for every month that passed, Sony’s PlayStation gobbled up more shelf space, more headlines, and more hearts.

Nintendo Buys Time with SNES Blockbusters

With the Ultra 64 delayed and competitors already knee-deep in next-gen launches, Nintendo faced a critical question: how do you keep your loyal fanbase engaged while the future is still cooking? The answer came from the past. Or more specifically, the 16-bit powerhouse that still had some gas left in the tank—the Super Nintendo.

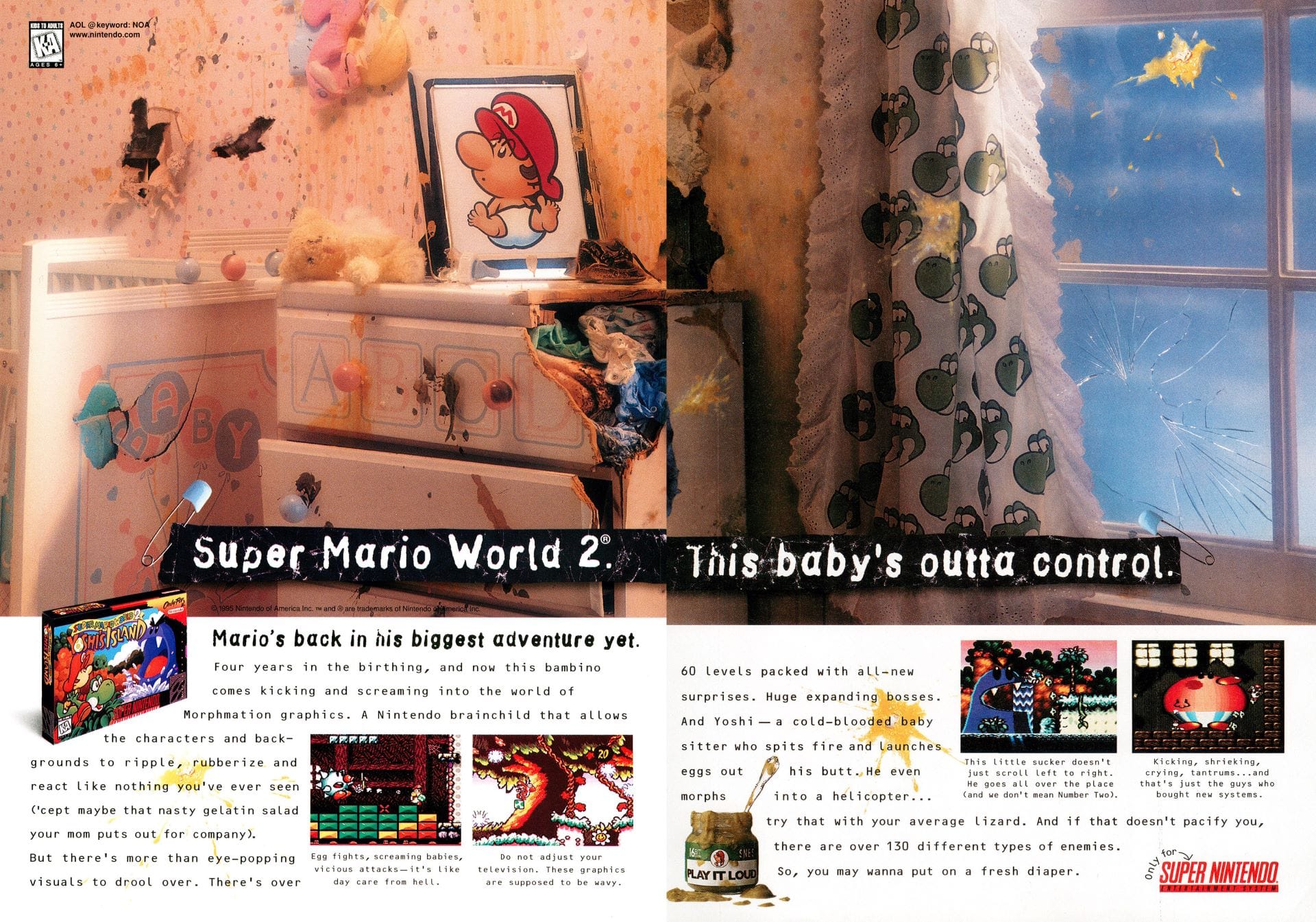

Between 1994 and 1995, Nintendo unleashed a final wave of all-time greats. Chrono Trigger brought time-traveling drama and jaw-dropping pixel art. Donkey Kong Country stunned players with its pre-rendered visuals and tight platforming. Yoshi’s Island flipped expectations with crayon-colored levels and one of the most expressive engines on the SNES. And let’s not forget Killer Instinct, EarthBound, and Super Mario RPG. These weren’t just filler—they were among the best games the SNES ever saw.

This end-of-era renaissance kept Nintendo in the public eye and softened the blow of the Ultra 64’s delay. While gamers were curious about CDs and 3D polygons, many were still glued to their Super Nintendos—thanks in large part to a catalog firing on all cylinders.

Nintendo, ever the master of pacing, knew how to make old hardware feel new again. These late-stage SNES releases were marketed with the same urgency and spectacle as any new console launch. Commercials boomed. Magazines hyped. And players kept buying.

Internally, Nintendo was buying time—for developers to get comfortable with 3D, for hardware bugs to be squashed, and for the Ultra 64’s identity to fully crystallize. But externally, it looked like confidence. While Sony and Sega rushed to define the next generation, Nintendo kept feeding fans experiences that were polished, imaginative, and timeless.

In hindsight, it was a masterclass in brand stewardship. The SNES didn’t limp across the finish line—it sprinted. And that momentum helped carry Nintendo forward, even as their new console stayed stuck in the lab.

Sony Strikes Back: The PlayStation’s Rapid Rise

While Nintendo delayed and fine-tuned, Sony went to war—with style, strategy, and a studio arsenal that came out swinging. They weren’t just launching a console—they were launching a cultural movement.

Sony’s acquisition of Psygnosis, makers of Lemmings and the eye-meltingly fast WipEout, gave the PlayStation street cred and design swagger. Namco brought Ridge Racer and Tekken, delivering arcade-perfect experiences on day one. Ubisoft and other third-party partners filled in the blanks, offering variety and freshness that no one expected from a brand-new platform holder.

By the time the PlayStation hit North American shelves, it wasn’t just another console—it was the console. Affordable. Cool. Packed with games that looked and sounded futuristic. Sony had arrived, and they weren’t playing catch-up—they were setting the pace.

Sony’s approach was ruthless and brilliant. They undercut Sega on price. They out-hyped Nintendo in the media. They blitzed TV screens and magazines with ads that felt more like music videos than commercials. The PlayStation wasn’t just a toy—it was a lifestyle product aimed at teenagers and twenty-somethings who were aging out of Mario and looking for something edgier.

Third-party developers flocked to Sony’s open, CD-friendly ecosystem. Licensing terms were generous. Development tools were accessible. Creative boundaries stretched wide. While Nintendo enforced strict control over who made what (and how), Sony rolled out the red carpet for innovation and experimentation.

Suddenly, the console market wasn’t just about mascots and memory—now it was about who could offer developers the most freedom and gamers the most choice.

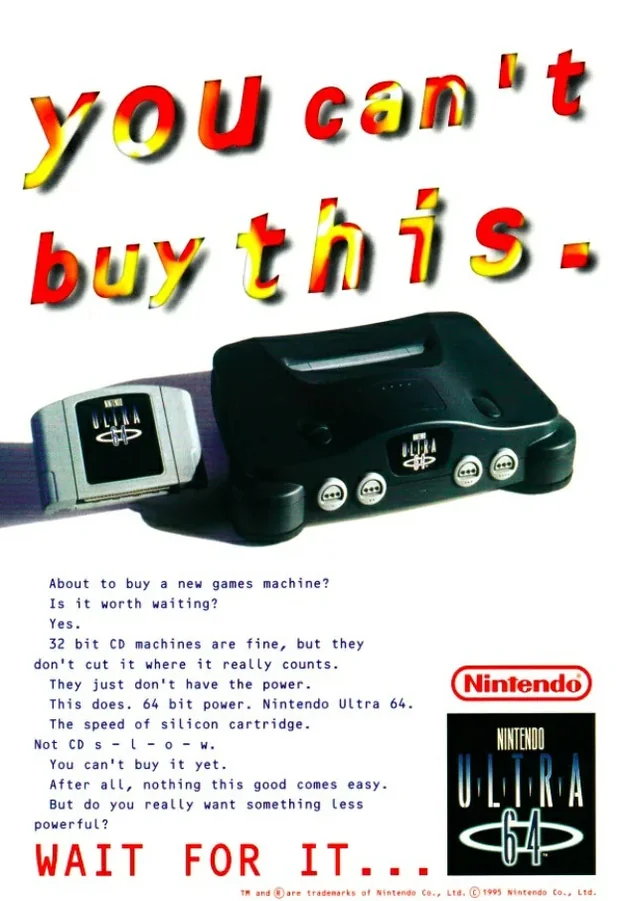

In a last-ditch effort to slow Sony’s momentum, Nintendo launched an ad campaign urging players to “wait for Ultra 64.” They leaned into the 64-bit power of their delayed system, implying the PlayStation was yesterday’s tech dressed in tomorrow’s clothes.

But the strategy flopped. Gamers had already seen what PlayStation could do—and more importantly, what it had. The Ultra 64 was still a mystery. Sony had actual games on shelves. Nintendo had tech demos, vague promises, and a controller nobody could quite figure out.

Meet the Nintendo 64

By late 1995, Nintendo was finally ready to pull back the curtain. At the Shoshinkai trade show in Japan, the company officially unveiled its long-delayed console under its final name: the Nintendo 64. Gone was the “Ultra” branding—clean, simple, and futuristic, the new name emphasized its most talked-about feature: 64-bit processing power.

The event was a spectacle. Nintendo knew they were late, but they were confident that what they had in the works would blow the competition away. The console’s form factor, controller, and upcoming game lineup were all shown off to massive fanfare. While the industry buzzed about Sony’s early success, Nintendo made it clear—they weren’t just back; they were ready to redefine the medium.

The N64 wasn’t just powerful—it was different. Instead of riding the CD wave like its rivals, Nintendo focused on speed and performance. The console boasted 64-bit architecture, advanced anti-aliasing, and a custom graphics chip from Silicon Graphics.

But it wasn’t just the internals that turned heads. The N64 came standard with four controller ports, a move that signaled Nintendo’s commitment to local multiplayer chaos—a feature that would later birth Mario Kart 64, GoldenEye 007, and Smash Bros.

Then there was the controller itself: a wild three-pronged design with a central analog joystick that felt alien at first—but once players saw how smoothly it controlled Mario in 3D space, it made perfect sense. Paired with the innovative “C-buttons” to manage the camera, it was clear this was a machine built for a new kind of game.

Perhaps the most tantalizing tease at Shoshinkai was the Final Fantasy tech demo. A full-motion glimpse at what Square’s legendary RPG series might look like running on Nintendo’s new powerhouse—fans were ecstatic. It suggested that the N64 would continue the rich RPG legacy built on the NES and SNES.

At Shoshinkai 1995, the Nintendo 64 felt like the future. Bold. Bizarre. Full of potential. A fresh start for a company trying to reclaim its throne.

The N64 Controller: Alien Design, Future-Defining Tech

When the Nintendo 64 controller was first unveiled, it looked like something out of a sci-fi movie—a three-pronged boomerang with a joystick in the middle and a trigger underneath. Critics were confused. Gamers were skeptical. But once Super Mario 64 hit, everything changed.

That analog stick? It wasn’t just a novelty—it was a revelation. Suddenly, players could ease Mario into a tiptoe, sprint across open fields, or pull off tight turns with fluid precision. The joystick enabled more expressive control than any D-pad could dream of. It was intuitive, immersive, and—for 3D gaming—absolutely necessary.

The controller’s radical shape invited new ideas. While most players gripped the middle and right handles for analog play, 2D throwbacks still made sense when holding the outer grips. It was two controllers in one—fitting for a console straddling two eras.

Another curveball: the C-buttons. Labeled “C” for “camera,” these yellow buttons gave players real-time control over their point of view. In Super Mario 64, they were essential—nudging the camera to peek around corners, adjust angles mid-jump, or line up a tricky platform. Combined with the analog stick, it created an unprecedented sense of spatial control. Moving through a 3D world didn’t feel awkward—it felt empowering.

And while later generations would refine the concept with dual sticks, the N64 laid the groundwork. It was the first mainstream console to take 3D control seriously—and it showed.

Sony’s original PlayStation controller? Pure 2D DNA. Sega’s Saturn pad? An evolution of arcade fighters. Both companies were still thinking in sprites and side-scrolling stages.

Nintendo, by contrast, designed its controller specifically for 3D movement. No compromises. No retrofitting. The analog stick, the Z-trigger, the camera buttons—all of it screamed forward-thinking. When Sony eventually added dual analog sticks and later introduced the DualShock, it wasn’t just innovation—it was catch-up.

The N64 controller wasn’t perfect—it was awkward for some games and lacked a second stick—but in terms of shaping the future of console input, it was a lightning strike. Weird, wonderful, and undeniably ahead of its time.

Super Mario 64: The Game That Changed Everything

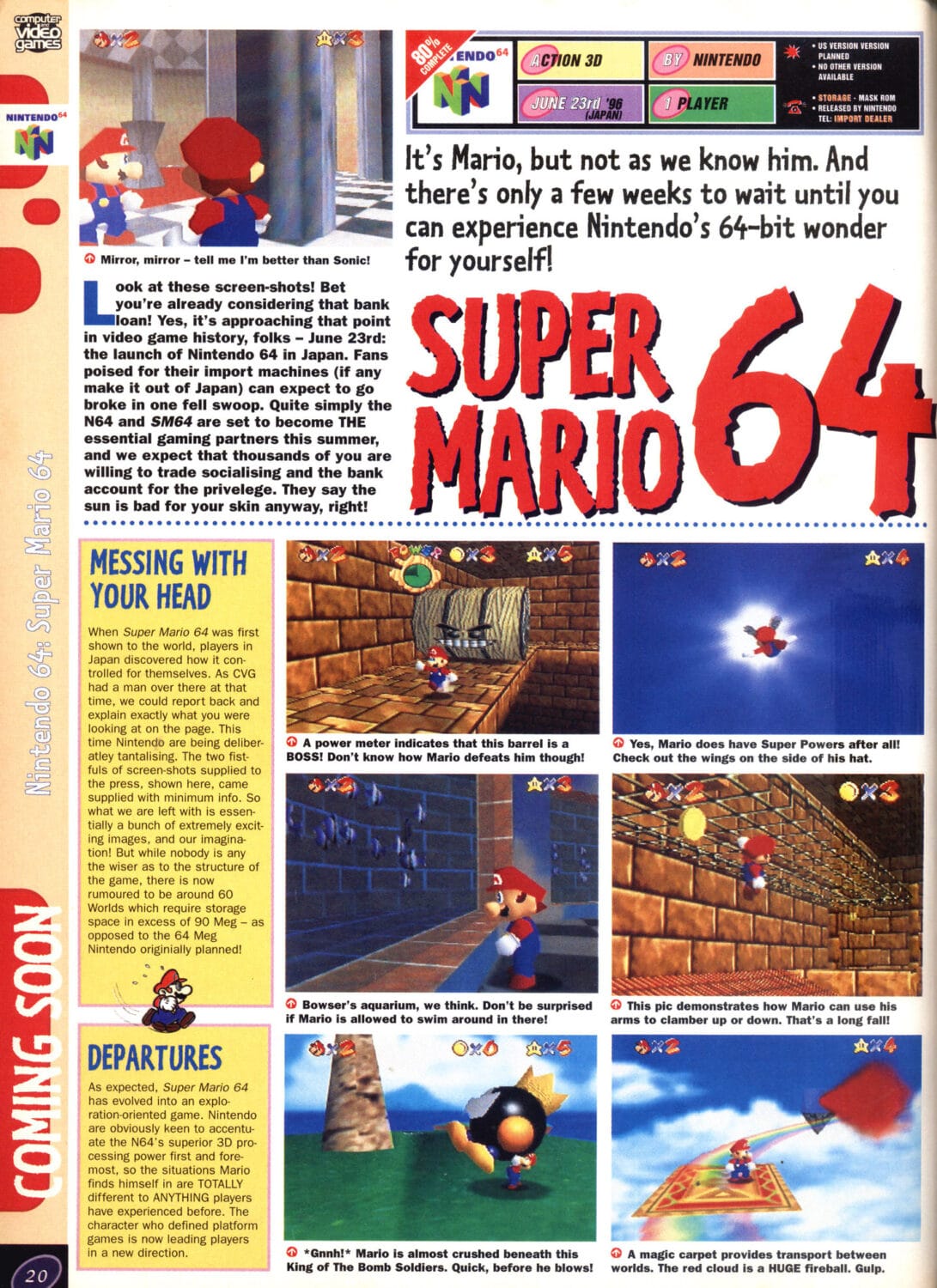

At Shoshinkai 1995, amidst all the hardware reveals and tech talk, one thing stole the show—and it wasn’t the console itself. It was Super Mario 64. The beta version of the game was playable, and the buzz around it was electric. Journalists, developers, and fans alike waited in line for hours just to get a few minutes with it.

What they found wasn’t just a new Mario game—it was a whole new way to play games. The freedom of movement, the way Mario reacted to analog input, the responsiveness of the controls—it was unlike anything the gaming world had seen. And this wasn’t pre-rendered smoke and mirrors; it was real, in-engine, and absolutely mind-blowing.

Gone were the linear left-to-right levels. Super Mario 64 dropped players into vibrant, open-ended 3D playgrounds filled with secrets, surprises, and challenges that could be approached in multiple ways. You could swim, fly, wall-kick, crawl, triple-jump—and every move felt deliberate, fluid, and fun.

The game redefined what a platformer could be. It wasn’t about getting to the end of a level—it was about exploring, experimenting, and mastering the space around you. Stars were earned through skill and creativity, not just reflexes. And each world felt like a mini-sandbox, encouraging replayability and discovery.

This wasn’t just evolution—it was revolution. Suddenly, every developer in the world had to rethink how 3D movement and camera design worked. Super Mario 64 set a standard so high that it would take years for others to catch up.

For all the hype around 64-bit graphics and cutting-edge tech, it was Mario who truly sold the Nintendo 64. Super Mario 64 didn’t just demonstrate what the console could do—it justified its entire existence. It was the proof-of-concept, the masterpiece, the reason to own the system on day one.

Reviews at the time were near-unanimous: this wasn’t just the best 3D game yet—it might be the best video game, period. And it wasn’t just critics. Players bought the game in droves, with many copies of Mario 64 selling one-to-one with the console itself at launch.

In a world suddenly obsessed with polygons, Super Mario 64 wasn’t just an early contender—it was the gold standard. A technical marvel, a design triumph, and the killer app that made the Nintendo 64 unforgettable.

The Square Breakup: Nintendo’s Biggest Loss

By the mid-’90s, tensions between Nintendo and Square were simmering. While the two had forged one of gaming’s most legendary partnerships during the NES and SNES eras, things were beginning to sour. The immediate issue? Nintendo’s delay of Super Mario RPG. Square had poured time and resources into the title, only to be told late in development to make additional changes—delays that frustrated the studio’s tight schedules and strained creative autonomy.

But the root of the issue went deeper. Square, like many developers, was growing increasingly weary of Nintendo’s rigid control over development and publishing. Combined with the technical limitations of cartridges—expensive to manufacture, small in capacity, and restrictive for ambitious projects—Square was ready to walk.

Enter Sony. Looking to bolster the PlayStation with must-have exclusives, they offered Square something Nintendo wouldn’t: creative freedom, cheaper media, better royalty terms, and global publishing support. For a company as visionary and forward-thinking as Square, it was a dream scenario.

Final Fantasy VII, already planned as a genre-defining RPG epic, simply couldn’t exist on cartridges. The game would eventually span three full CDs, with pre-rendered cinematics, orchestral music, and sprawling environments—all impossible on the Nintendo 64’s limited storage. Square made the leap—and in doing so, made history.

Square’s departure wasn’t an isolated incident—it was a signal flare. If Nintendo could lose their most iconic third-party partner, anyone could leave. Soon after, Enix—the creators of Dragon Quest—also shifted focus to the PlayStation. Smaller studios followed suit, and even long-time Nintendo allies began hedging their bets.

The N64, once poised as the most powerful console of its generation, suddenly found itself starving for RPGs—one of the most important genres of the time. As Sony’s PlayStation flooded store shelves with cinematic, story-rich adventures like Xenogears, Suikoden, and Legend of Dragoon, Nintendo’s console leaned almost entirely on first-party hits.

The Square breakup wasn’t just a missed game—it was a generational shift. One that helped the PlayStation crush its competition and left Nintendo scrambling to fill the gaps.

Building the Legacy: Games That Kept the N64 Alive

With fewer third-party allies and a late start, Nintendo needed heavy hitters—and it found them. Mario Kart 64 took the beloved SNES formula and injected it with 3D tracks, zany items, and four-player chaos. Sleepovers, college dorms, living rooms—it became the social event of the late ’90s.

Then came GoldenEye 007, the unlikeliest of masterpieces. A movie tie-in developed by a relatively unknown team at Rare, it became the defining first-person shooter on consoles. Four-player deathmatches, proximity mine traps in the Facility, and slappers-only duels—GoldenEye turned the N64 into the home of competitive couch play.

These weren’t just great games—they were cultural events. They proved that the N64 didn’t need CDs to be unforgettable. All it needed was a controller, some friends, and a few hours to kill.

While Sony was introducing new, mature-facing icons, Nintendo doubled down on its character-first philosophy—but with fresh faces and bold spins. Banjo-Kazooie, developed by Rare, was a platforming gem that rivaled Super Mario 64 in creativity, with lush worlds, cheeky humor, and a collect-a-thon formula that became a genre of its own.

Then came Super Smash Bros.—a chaotic brawler that asked the question no kid had ever dared to answer out loud: who would win in a fight, Mario or Link? The result was a new kind of fighting game, one focused on accessibility, mayhem, and beloved franchises colliding in pure Nintendo fashion.

These games not only expanded Nintendo’s character lineup—they reinvigorated it. Suddenly, even lesser-known faces had a shot at stardom.

With Square and Enix gone, Nintendo needed a creative partner to help shoulder the load. Enter Rare. The UK-based developer wasn’t just good—they were on fire. From Diddy Kong Racing to Jet Force Gemini, Rare delivered hit after hit, pushing the N64 hardware in ways even Nintendo didn’t.

They filled the gaps that third-party studios left behind, and gave the N64 a library that, while smaller than the PlayStation’s, was bursting with character and innovation.

In many ways, Rare became the unofficial second-party powerhouse that helped define the N64 era. Without them, the console might have faded faster. With them, it stood tall—quirky, confident, and defiantly fun.

Accessories, Experiments, and Missteps

In an era when consoles were sold as self-contained machines, Nintendo once again chose to zig where others zagged. Enter the Expansion Pak, a small red-topped module that slid neatly into the N64’s memory slot. On paper, it sounded unglamorous—just an extra 4MB of RAM. In practice, it became the key to unlocking some of the console’s most ambitious titles.

Games like Donkey Kong 64 and Perfect Dark leaned on it heavily, with the latter outright demanding it just to run the full experience. Suddenly, players were experiencing sharper textures, less suffocating fog, and larger, more intricate worlds than the base hardware could comfortably handle. Majora’s Mask, too, would join the list of must-have Expansion Pak titles, cementing the accessory as more than a novelty.

But the add-on came with a trade-off. It created a split library where some games worked without it, others improved with it, and a few outright refused to run unless you owned the upgrade. Parents grumbled about hidden costs, while kids debated whether the performance boost was worth the pocket money. Still, for the devoted, the Expansion Pak represented Nintendo’s determination to push the machine harder than its specs should’ve allowed—proof that the N64’s ceiling wasn’t fixed, even if the industry had already moved on to sleeker machines.

If the Expansion Pak was Nintendo’s small but useful gamble, the 64DD was its moonshot gone terribly wrong. Announced with lofty promises in the mid-’90s, this magnetic disk add-on was supposed to revolutionize the Nintendo 64. Disks would offer more storage than cartridges, allow rewritable saves, and even open doors to online connectivity—an almost sci-fi concept for consoles at the time. Nintendo pitched it as the bridge between traditional gaming and a future where players could create, share, and expand their experiences.

But by the time the 64DD finally limped out in late 1999, the magic had evaporated. Only available in Japan through a limited mail-order service, it launched years late, was priced high, and with barely a trickle of compatible software. The library was pitiful—curiosities like the Mario Artist suite, a quirky online service called Randnet, and expansions for F-Zero X that only diehard fans ever saw. The bold vision of user-generated content and internet-driven play was crippled by poor timing, lack of marketing, and a rapidly changing industry that had already moved past Nintendo’s experiment.

Outside Japan, the 64DD may as well not have existed. For Western gamers, it became little more than a rumor, a ghost add-on whispered about in magazine previews but never materializing on store shelves. By then, PlayStation was dominating globally, and the upcoming PS2 was promising not just gaming, but a full-blown entertainment hub.

The 64DD wasn’t just a commercial failure—it was a reminder that even Nintendo, the master of quirky innovation, sometimes aimed too far ahead of its audience. It was an idea born at the wrong time, strapped to a console already gasping for air.

Overshadowed by Rivals

By the late ’90s, the Nintendo 64 was living a strange double life. On one hand, it was the machine of Super Mario 64, GoldenEye, Ocarina of Time, and Mario Kart—titles that practically wrote the book on modern 3D design. On the other hand, it was being outsold and outpaced by Sony’s PlayStation, which had become the de facto home of cutting-edge RPGs, cinematic storytelling, and a flood of third-party creativity.

While PlayStation’s library swelled with over 2,000 games globally, the N64’s catalog felt bare by comparison—fewer than 400 titles in total, many of them first-party. And with each passing year, Sony’s machine became more than just a console; it was a cultural hub. It was where teens played Final Fantasy VII, where college dorms echoed with Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater, where experimental studios could actually afford to take risks thanks to the lower cost of CDs.

By the close of the decade, the gaming landscape was shifting at breakneck speed. Sony, having already seized the crown with the PlayStation, wasn’t content to rest on its laurels. At Tokyo Game Show 1999, the company unveiled the PlayStation 2, a machine that didn’t just promise prettier polygons—it promised to be the centerpiece of your living room. It doubled as a DVD player, a selling point that proved irresistible in an era when standalone DVD players still carried a hefty price tag. For many households, the PS2 wasn’t just their next console; it was their first affordable step into the future of home entertainment.

Meanwhile, another titan was preparing to storm the field. Microsoft, flush with cash and eager to expand its empire beyond Windows, announced its intent to enter the console wars with the Xbox. With the financial muscle to go toe-to-toe with Sony and a growing ecosystem of developers enticed by the prospect of powerful hardware and online connectivity, Microsoft’s arrival was seismic.

For Nintendo, the timing couldn’t have been worse. The N64, while beloved, was already sagging under the weight of lost third-party support and its cartridge handicap. Now, not only was Sony poised to consolidate its dominance with a multimedia powerhouse, but a new rival loomed on the horizon—one that understood software ecosystems and online infrastructure better than anyone.

The once-clear battlefield of Sega versus Nintendo had mutated into a three-way clash, and in the scramble for relevance, the N64 looked increasingly like yesterday’s news. Its innovations were still admired, its games still celebrated, but the future belonged to machines that offered not just great play, but versatility and scope. Nintendo knew it was time to regroup and rearm, which is why whispers of its successor—codenamed Project Dolphin—began to surface.

For weary N64 owners, the whispers of a next-gen console brought both relief and excitement. Rumors swirled about cutting-edge graphics, long-awaited new entries in flagship series, and a return to the kind of third-party support that had abandoned Nintendo during the fifth generation. Developers were said to be getting early kits, and anticipation grew that Nintendo was ready to shed the baggage of its past decisions. When the GameCube was finally released in 2001, it marked the beginning of a new chapter, with Nintendo bracing itself for a new kind of console war.

Was The Nintendo 64 A Commercial Failure?

When the dust settled, the numbers painted a sobering picture. The Nintendo 64 sold just under 33 million units worldwide—a respectable tally in isolation, but dwarfed by Sony’s PlayStation, which surged past 100 million. Third-party developers had largely abandoned ship, the cartridge format strangled its library, and rivals outpaced it with cheaper media and broader support. From a business standpoint, the N64 looked like a misstep, a stumble from a company once untouchable.

At launch, the N64’s analog stick was viewed as a curiosity. Within a few years, it became an industry standard. Sony responded quickly with the Dual Analog controller, then cemented the idea with the now-iconic DualShock. Sega followed with the Saturn 3D controller and later refined it on the Dreamcast.

But it was Nintendo that took the first big leap—proving that 3D worlds demanded a new kind of precision. From platformers to shooters, analog sticks allowed for movement that felt fluid, nuanced, and natural. Today, every major console controller owes a debt to that bold three-pronged design.

Beyond the controller, the Nintendo 64 helped define the very language of 3D game design. Super Mario 64 set the blueprint for third-person movement. Ocarina of Time introduced lock-on targeting and context-sensitive buttons—mechanics now common in action and adventure games.

Level design, camera control, environmental storytelling—N64 games like Banjo-Kazooie, Star Fox 64, and Majora’s Mask challenged players to think in 3D space in ways 2D simply couldn’t. These weren’t just technical experiments—they were creative revolutions.

Even with its smaller library, the N64 left an outsized influence on game design that can still be felt today.

Nintendo’s decision to stick with cartridges was heavily criticized—and rightfully so. It drove away developers like Square, limited storage capacity, and pushed up production costs. The PlayStation’s expansive CD format offered more content, more cutscenes, and more support from ambitious studios.

But the trade-off came with a silver lining: speed and reliability. No load times. No disc swapping. Instant boot-ups. Developers who embraced the hardware—especially Nintendo and Rare—crafted games that were fast, responsive, and so well optimised that they would struggle to run on a CD-based console.

Super Mario 64, F-Zero X, Smash Bros., Ocarina of Time—these weren’t just technical marvels; they were timeless. Games that still hold up because of the tight, snappy experiences only cartridges could provide at the time. In the end, Nintendo’s choices weren’t always safe—but they were forward-thinking. And even when they lost market share, they moved the industry forward.

So, was the N64 a commercial failure? Compared to the PlayStation juggernaut, undeniably. But was it a cultural triumph, an experimental console whose ideas reshaped the medium? Absolutely. The N64 lived and died as a contradiction: underwhelming in raw sales, yet immortal in its impact. For a whole generation of players, it wasn’t just another box under the TV—it was the console that changed how games felt, looked, and played forever.

Conclusion

The Nintendo 64 wasn’t built to blend in—it was built to blaze a trail. From its polarizing controller to its defiant use of cartridges, every inch of the N64 screamed boldness. Sometimes that risk paid off in groundbreaking ways. Other times, it cost Nintendo dearly.

The N64 didn’t win the console war. It didn’t dominate sales charts. But it changed the rules. Its DNA lives on in every analog stick you touch, every 3D world you explore, every multiplayer match you share on a couch with friends. For Nintendo, the N64 was both a triumph and a wake-up call. It proved that innovation alone isn’t enough—you need support, infrastructure, and third-party trust. But it also showed the power of first-party excellence, hardware-software synergy, and creative conviction.

The N64 proved that a console could fall short as a product yet still dominate as a cultural force, etching its name into gaming history with a library of masterpieces that still shine brighter than any sales figure. It was the console that dared to be different—flawed, fearless, and unforgettable. And decades later, its legacy is still shaping how we play.