At the dawn of the new millennium, arcades stood at an uncertain crossroads—caught between the twilight of coin-op dominance and the home console revolution raging through living rooms worldwide. But just as some whispered the death of the arcade, Namco and Sony threw a curveball. Enter: the Namco System 246. Simple on the surface, this PS2-powered titan would quietly ignite a second wind for arcade gaming, offering developers the seductive fusion of familiar architecture and arcade-grade horsepower.

Built around the same silicon heart that pulsed inside the PlayStation 2—the Emotion Engine and Graphics Synthesizer—System 246 wasn’t just another board; it was a bold recalibration. A plug-and-play canvas for creators. A playground for experimentation. From stylized weapon duels in Soulcalibur II to the adrenaline-drenched drift of Wangan Midnight, this machine became a backstage pass to the future. The year 2000 didn’t kill the arcade—it rearmed it. And Namco, with Sony’s circuitry humming under the hood, led the charge.

Successor to the System 11 Legacy

Before System 246 stormed onto the scene, Namco’s arcade dominance rested on the shoulders of its System 11 and System 12 hardware—boards that were essentially modified PlayStation tech, optimized for the golden age of 3D fighters. Titles like Tekken 3 and Soul Edge weren’t just hits—they were seismic events that reshaped the arcade landscape. But as the PS1-era hardware began to creak under the weight of new visual expectations, a changing of the guard was inevitable. System 246 arrived not as a reset, but as an evolution.

Tekken 3 had set the gold standard on System 12, but Tekken 4—and later, the refined Tekken 5: Dark Resurrection—took the franchise to staggering new heights on System 246. The jump in animation fluidity, texture fidelity, and stage interactivity was undeniable. Characters moved with more weight, more grace, more humanity. Real-time lighting added dimension to brutal uppercuts and explosive juggles. Namco wasn’t just chasing graphical upgrades—they were reimagining the rhythm and drama of a fight.

Developers were waking up to a new reality: games no longer had to live solely in the arcade or on the couch. With System 246 mirroring the PS2’s architecture, developers could build once and deploy twice—first in arcades to test mechanics and audience reaction, then at home with expanded content. This console-to-arcade synergy saved time, slashed costs, and supercharged creativity. It was a paradigm shift, echoing Sega’s Naomi strategy, but with the mainstream muscle of the PlayStation brand. Portability wasn’t a perk—it was a game-changer.

Inside the Machine: System 246 Hardware Deep Dive

In an era when arcade hardware was often esoteric and developer-hostile, the Namco System 246 dared to be familiar. It took the beating heart of the PlayStation 2—the best-selling console of all time—and adapted it for the smoky, neon-lit battlegrounds of the arcade floor. It wasn’t just clever—it was strategic.

At a glance, the Namco System 246 might seem like just a PS2 in an arcade shell—but under the hood, it was a finely tuned performance machine. Built to endure the relentless demands of arcade usage, its architecture fused raw console power with arcade-grade durability and adaptability. This was more than a simple board—it was a blueprint for the future of hybrid game development.

At the core of the System 246 was Sony’s Emotion Engine, a 300 MHz beast designed for real-time physics, advanced AI, and lightning-fast calculations. Originally built to power immersive console epics, this processor was now thrust into the brutal world of fighting games, racers, and rhythm spectacles. In the arcade, it wasn’t about long narratives or cutscenes—it was about speed, impact, and split-second response. The Emotion Engine delivered with relentless efficiency.

Backed by a 150 MHz Graphics Synthesizer with 48GB/sec memory bandwidth, the System 246 didn’t just emulate PS2 visuals—it pushed them harder. The arcade’s demands for fluid animation, explosive effects, and detailed models were met with stunning fidelity. Games like Soulcalibur III: Arcade Edition and Tekken 5: Dark Resurrection looked as good—if not better—than their home counterparts, running on screens built for the spectacle.

One of the System 246’s most unsung innovations was its use of standard optical and hard disk formats. While other boards were locked into proprietary media, the 246 could boot from CD-ROM, DVD-ROM, or a dedicated HDD, giving developers the freedom to scale assets, patch builds, and manage data like never before. It was arcade infrastructure with console pragmatism—and it made the development pipeline faster, cheaper, and smarter.

System 246’s Secret Weapon: Versatility in Control Interfaces

What truly set the Namco System 246 apart wasn’t just its silicon muscle—it was its unmatched flexibility. This wasn’t a board locked into one genre or control scheme. Whether you were throwing punches, drifting through cityscapes, or pounding out a rhythm, the 246 adapted. It was a modular marvel, effortlessly accommodating a dizzying array of input types that allowed developers to think far beyond buttons and joysticks.

Fighting games thrived on the System 246, with Soulcalibur II and Tekken 5 using traditional arcade fight sticks to deliver tight, frame-perfect combat. But it didn’t stop there. Titles like The iDOLM@STER and Dragon Chronicle Online brought touchscreen gameplay into the arcade mix—an interface more often seen in handhelds or mobile games. This range made the 246 a true all-genre platform, accommodating hardcore fighters, casual players, and strategy fans alike.

One of the most iconic uses of the System 246’s analog capabilities came with Taiko no Tatsujin. Spanning entries 7 through 14, the series used authentic drum peripherals that read strike pressure and placement, turning rhythm into physical performance. The precision of the 246’s analog input support meant these games didn’t just play well—they felt alive, responsive, and tactile in a way few arcade experiences could match.

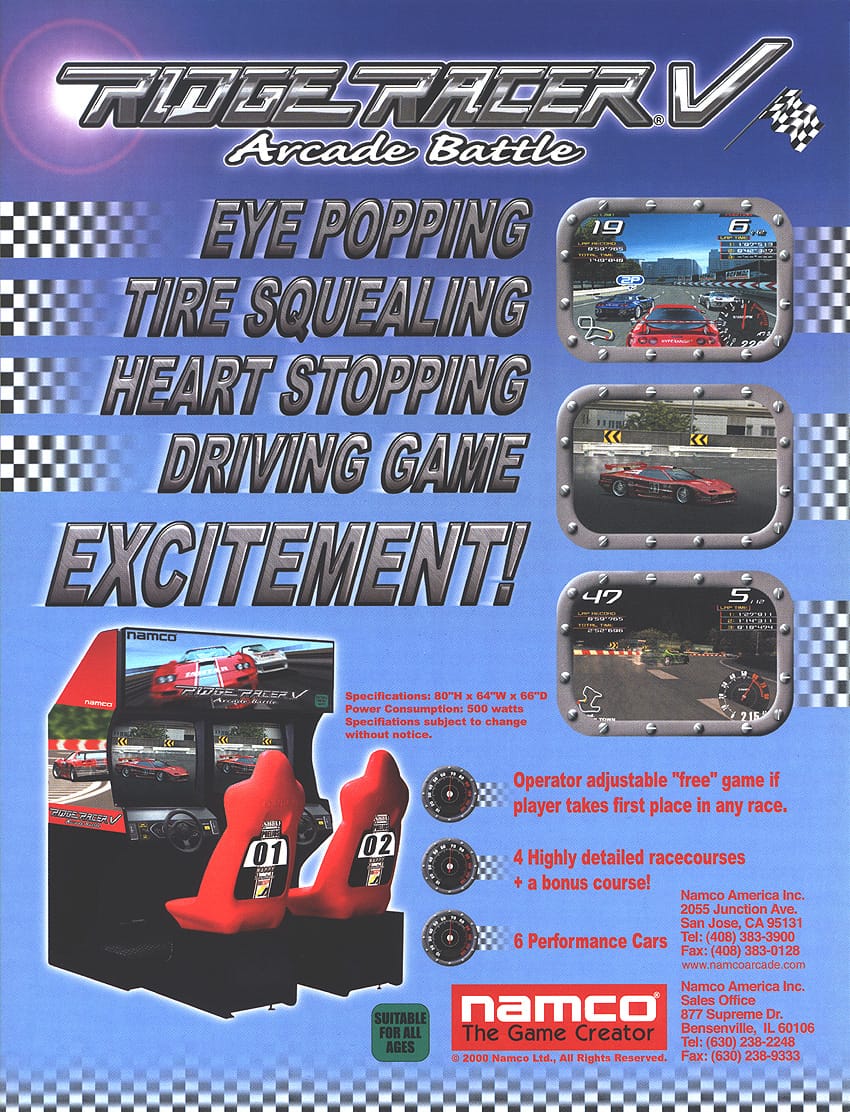

The board’s adaptability extended to force-feedback steering wheels, gear shifters, and calibrated light guns. Ridge Racer V: Arcade Battle offered smooth, high-speed control on par with top-tier racing sims, while Time Crisis 3 and Cobra: The Arcade delivered pinpoint-accurate shooting action with responsive pedal systems and dual-player support. This wasn’t just PS2 hardware in a cabinet—it was a chameleon platform, seamlessly transforming to suit the game’s needs.

Multiplayer, LAN, and Card-Based Progression

Long before online connectivity became standard in console gaming, the Namco System 246 was quietly pushing the boundaries of arcade interactivity. Beyond the joystick battles and rhythm smashes, the 246 was laying the groundwork for persistent progress, multiplayer showdowns, and a more personal arcade experience. It was a glimpse into the networked future—delivered through cabinets tucked into smoke-filled arcades and glowing game centers.

System 246 wasn’t just built for single-screen experiences. With LAN functionality baked in, developers could link multiple cabinets for real-time competitive play. Racing titles like Wangan Midnight and Battle Gear 3 let up to four players tear down highways side-by-side, complete with dynamic rubberbanding and rival stats. For fighting games, linked systems opened up tournament possibilities without lag or input delay—a crucial element for serious play.

The inclusion of IC card readers brought a game-changing twist: personal progression. Players could swipe a card to save stats, customize characters, and pick up where they left off. Games like Dragon Chronicle and The iDOLM@STER leaned heavily into this, encouraging repeat visits and deeper investment. This wasn’t just about high scores—it was about ownership. In an era where arcades were fading in the West, Japan was turning them into RPG hubs with tangible memories baked into plastic cards.

For certain high-profile titles, Namco deployed satellite cabinet setups—networked clusters of terminals around a central server. These allowed massive tournaments, dynamic matchmaking, and even event-based content updates. While modest by today’s standards, these systems laid the conceptual foundation for modern arcade networks like NESiCAxLive and ALL.Net. In a world still dominated by standalone machines, System 246 was thinking globally—even if only a few games fully realized the potential.

Media Formats and Storage Solutions

One of the System 246’s most forward-thinking strengths was its support for multiple storage formats—a rare luxury in the arcade space. While many competing boards relied on proprietary chips or fixed media, Namco and Sony embraced flexibility. Developers could choose the best medium for their game’s scope, budget, and update needs, dramatically shifting how arcade titles were built and maintained.

System 246 could boot from CD-ROMs for lighter titles, tap into the higher capacity of DVD-ROMs for asset-heavy games, or even load content directly from a hard disk drive for faster read speeds and complex installations. This tiered approach meant developers didn’t have to shoehorn ambitious concepts into tight formats—they could scale up or down depending on the vision. Fighting games like Tekken 4 loaded snappily off DVD, while HDD-based titles like Taiko no Tatsujin benefitted from low latency and ample space for music libraries and high-quality audio.

Storage wasn’t just a technical detail—it shaped gameplay. Larger media formats enabled richer environments, more characters, longer soundtracks, and smoother transitions. With hard drives, games could cache data mid-session, reducing load times and enabling persistent states for multiplayer sessions. This allowed developers to take risks—bigger arenas, complex audio design, and real-time content management that simply wasn’t feasible on older, ROM-locked systems. System 246 turned storage into a creative decision, not a limitation.

The System 246 Family Tree

Like any successful piece of arcade hardware, the System 246 didn’t stand still. As the industry evolved and game design ambitions expanded, Namco and Sony rolled out several hardware revisions—each tailored to meet specific needs. From power boosts to cost-cutting to bespoke configurations, these spin-offs kept the platform relevant for over a decade and gave developers fresh tools to work with.

System 256: The Enhanced Sibling Built for Bigger Games

Debuting as the high-powered successor, System 256 retained full backward compatibility with many System 246 titles while amping up memory and processing capabilities. Designed for more graphically demanding and content-rich experiences, it became the backbone for later arcade heavyweights like Tekken 5: Dark Resurrection and Soulcalibur III: Arcade Edition. It also improved load times and data throughput—crucial for large, fast-paced fighting arenas and story-driven content. System 256 wasn’t just a refresh—it was a response to escalating expectations.

System 147: A Curious Cut-Down with a Singular Purpose

Then came the oddball of the family—System 147. Stripped of the bells and whistles, this cost-reduced variant featured the game code directly flashed onto the board via ROM, eliminating removable media entirely. It was designed for simplicity, speed, and low maintenance. Yet despite its potential, only one game ever officially used it: Pac-Man Battle Royale. A curious footnote in the family tree, System 147 represented both an experiment in efficiency and a sign of changing times.

Special Editions: Time Crisis 4’s Unique Board

While System 256 carried most of the heavy-hitters, Time Crisis 4 required something different. Its custom version of the System 256 included specialized hardware to support enhanced light-gun functionality, more robust stage scripting, and additional I/O requirements. The result? One of the most technically impressive rail shooters of its generation—bursting with environmental effects, voiceovers, and synchronized peripherals. It was a reminder that even within a unified platform, Namco wasn’t afraid to tweak and tailor when the vision demanded it.

Best Namco System 246 Games

Over its decade-long reign, the Namco System 246 proved to be more than just a clever reuse of PlayStation 2 hardware—it was a launchpad for some of the most influential, genre-defining, and visually breathtaking arcade titles of the 2000s. From iconic 3D fighters to high-speed racers and anime brawlers with cult followings, the 246’s game library was a testament to its flexibility and technical muscle. Below are the marquee titles that made System 246 an arcade legend.

Ridge Racer V: Arcade Battle (2000)

One of the first titles to show off the System 246’s horsepower, Ridge Racer V: Arcade Battle was a refined, turbocharged version of the PS2 launch game. It marked a turning point for the franchise—less drift-heavy than its predecessors, but still oozing with arcade flair and techno-fueled swagger.

The Need for Speed, PS2 Style: Sleek visuals, high frame rates, and tight controls gave this racer a visceral sense of speed that felt at home in the arcade. The game supported LAN-linked cabinets for multiplayer battles, adding a social and competitive edge that the home version lacked.

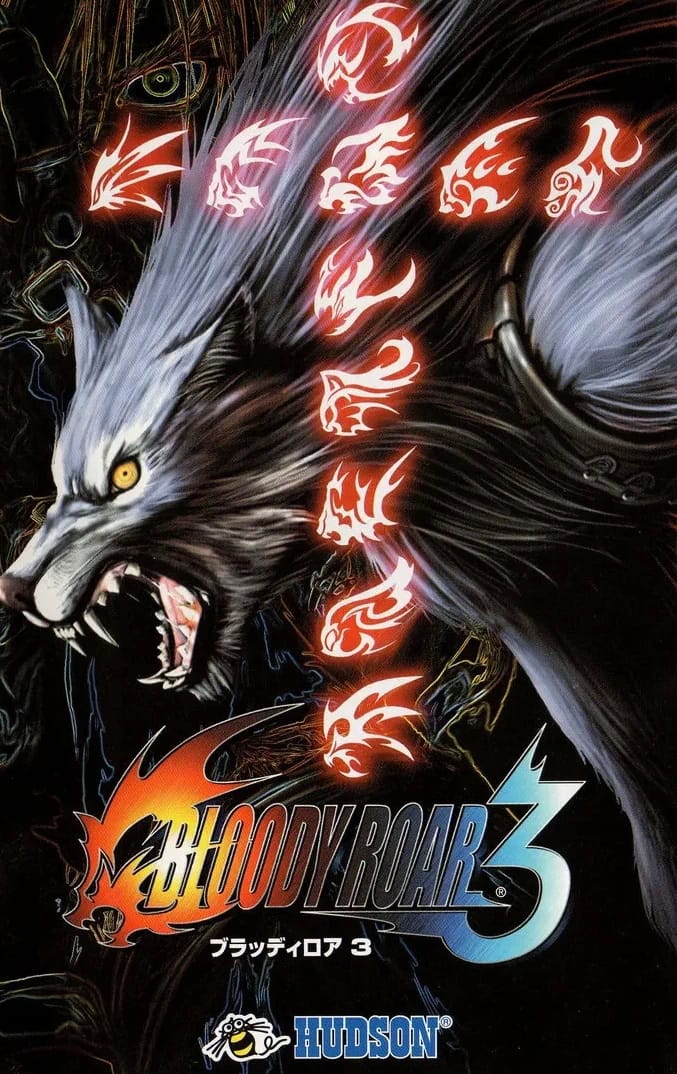

Bloody Roar 3 (2000)

Bloody Roar 3 might not have commanded the same attention as Tekken or Soulcalibur, but it offered something completely different: transformation-based brawling. Players could morph into beast forms mid-match, altering their movesets and strategies on the fly. The System 246 brought these transformations to life with snappy animations, detailed models, and impactful sound design.

Beastly Brawling in Full 3D: The game’s balance of speed, spectacle, and transformation mechanics made it a cult favorite and a standout among early 3D fighters on the platform.

Wangan Midnight (2001)

Based on the popular manga and anime, Wangan Midnight transformed Tokyo’s inner loop expressways into a street racing battlefield. Its high-speed duels, immersive cabinet setup, and LAN support turned it into a fixture in Japanese arcades. More than just a racer, it offered RPG-lite progression through car customization and a card-based save system, allowing players to build their machines over time.

High-Octane Battles Through Tokyo’s Expressways: The tight handling and cinematic sense of speed made full use of the System 246’s capabilities, making it a must-play for fans of the genre.

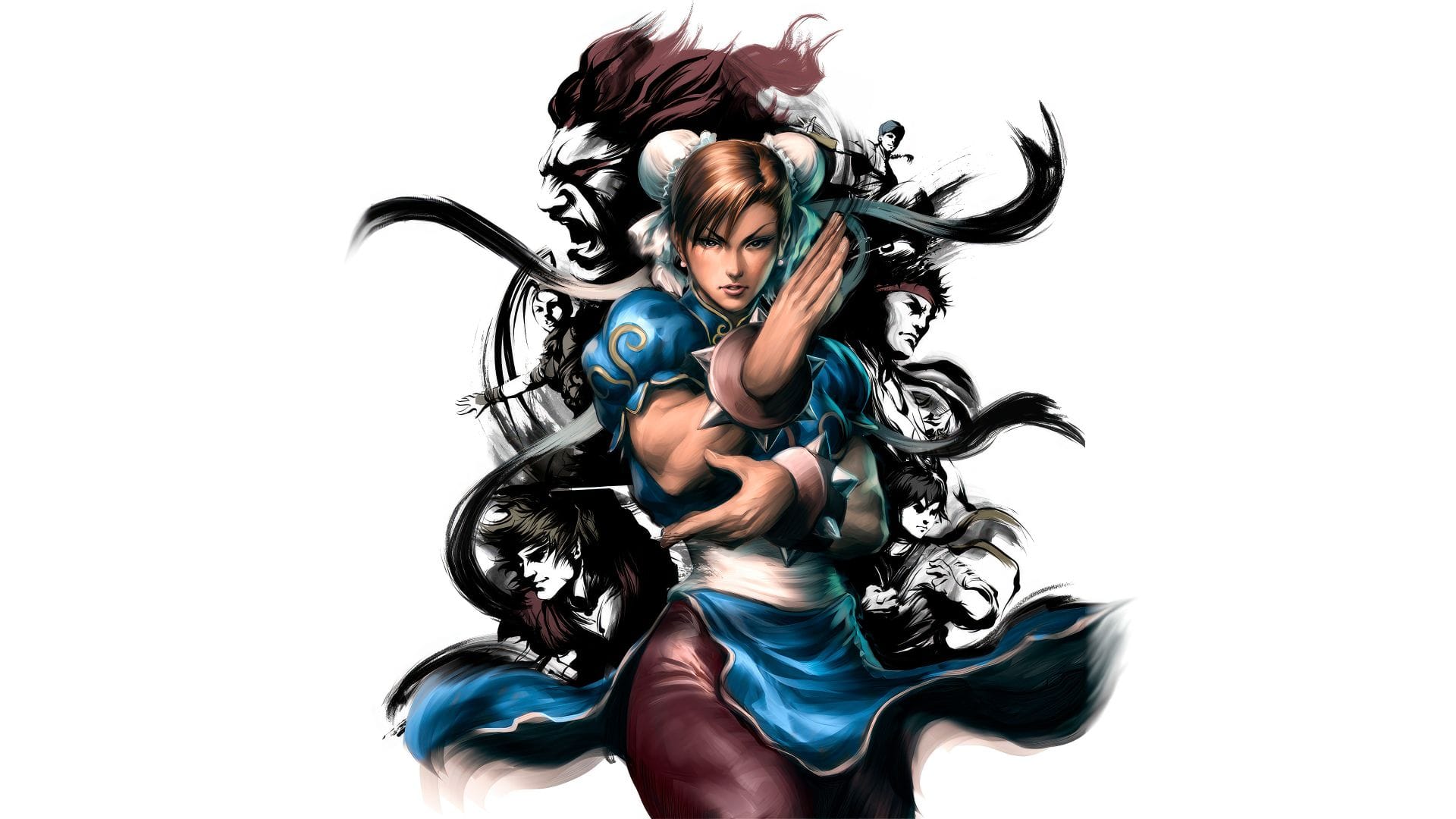

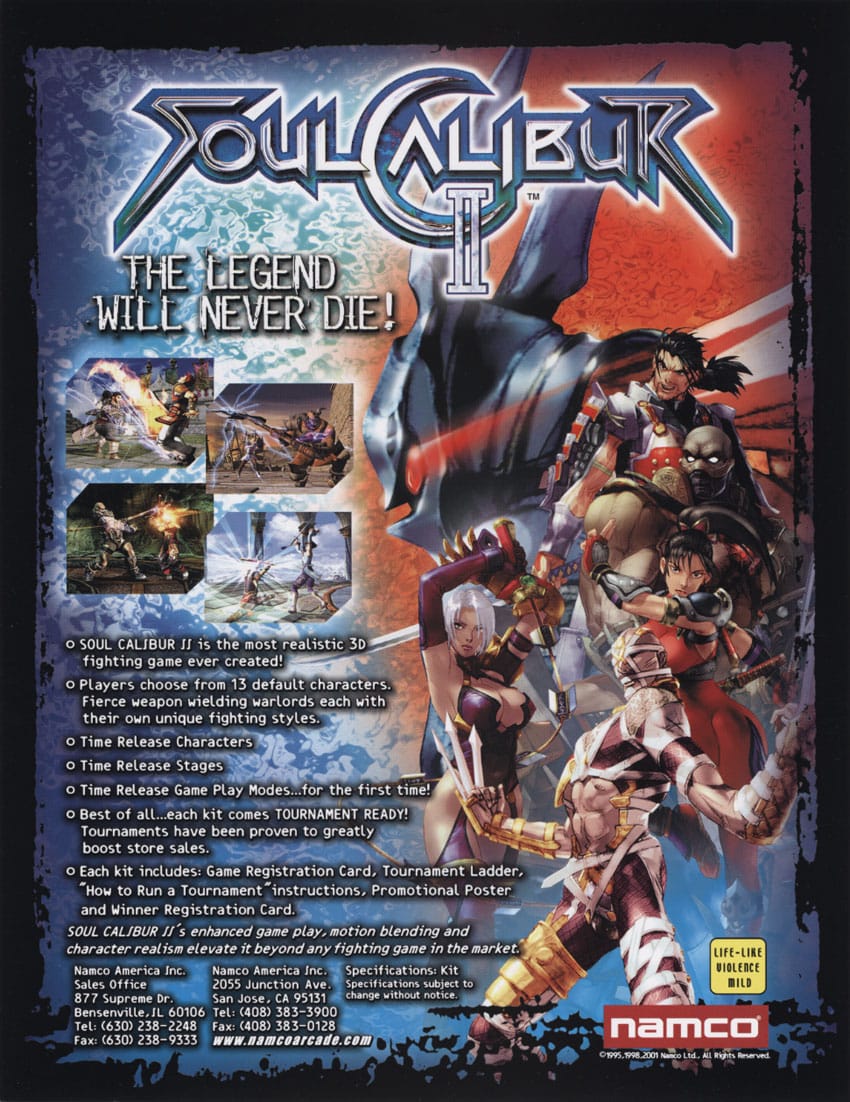

Soulcalibur II (2002)

When Soulcalibur II hit arcades in 2002, it felt like lightning in a bottle. Built on the System 246’s PS2 muscle, the game delivered a jaw-dropping leap in fidelity over its predecessor. Every swing, parry, and clash was rendered with meticulous attention to detail—glinting blades, dynamic camera sweeps, and fluid character animation that bordered on balletic. Soulcalibur II cemented the System 246’s reputation as a platform for serious, cinematic combat and raised the bar for the entire genre.

The Weapon-Based Fighter That Set Arcades Ablaze: It introduced beloved new fighters like Talim and Raphael, refined the signature 8-Way Run movement system, and balanced accessibility with a deep competitive layer. This wasn’t just an arcade fighter—it was an event.

Capcom Fighting Jam (2004)

A spiritual follow-up to Capcom Fighting Evolution, Capcom Fighting Jam on the Namco System 246 attempted to unify fighters from different eras of Capcom’s fighting legacy. It brought together characters from Street Fighter II, Alpha, Street Fighter III, Darkstalkers, and Red Earth—all operating under their original mechanics.

A Crossover Curiosity: While divisive among fans due to its balance quirks and reused sprites, the arcade version was notable for its crisp performance and responsive controls on the 246 hardware. It was a throwback cocktail that appealed to purists and curious newcomers alike, even if it didn’t dethrone Capcom’s crown jewels.

Tekken 5: Dark Resurrection (2005)

Few arcade games captured the hearts of competitive players like Tekken 5: Dark Resurrection. Originally built for the System 256 (fully compatible with 246 architecture), DR introduced new characters, stunning backdrops, and some of the most fluid 3D combat ever seen in an arcade. Its improved movement system, faster pace, and expanded roster revitalized the franchise.

A Fighting Game Milestone: It wasn’t just a graphical showcase—it was a mechanical rebirth that dominated arcades and later became a cult hit on the PSP and PS3. For many, Tekken 5: DR was the pinnacle of the series’ arcade legacy.

Super Dragon Ball Z (2005)

Unlike the 3D arena fighters that defined most Dragon Ball games, Super Dragon Ball Z took a more traditional approach, built with fighting game purists in mind. Developed by Crafts & Meister and published by Namco, the game featured cel-shaded visuals, tight 2D-plane movement, and a control scheme reminiscent of Capcom’s golden age fighters. The System 246 handled the colorful, explosive aesthetic with ease, keeping the action crisp and responsive.

Anime Arcade Action at Its Flashiest: Its high-skill ceiling and fan-service-heavy presentation earned it a loyal arcade following and a respected home port on PS2.

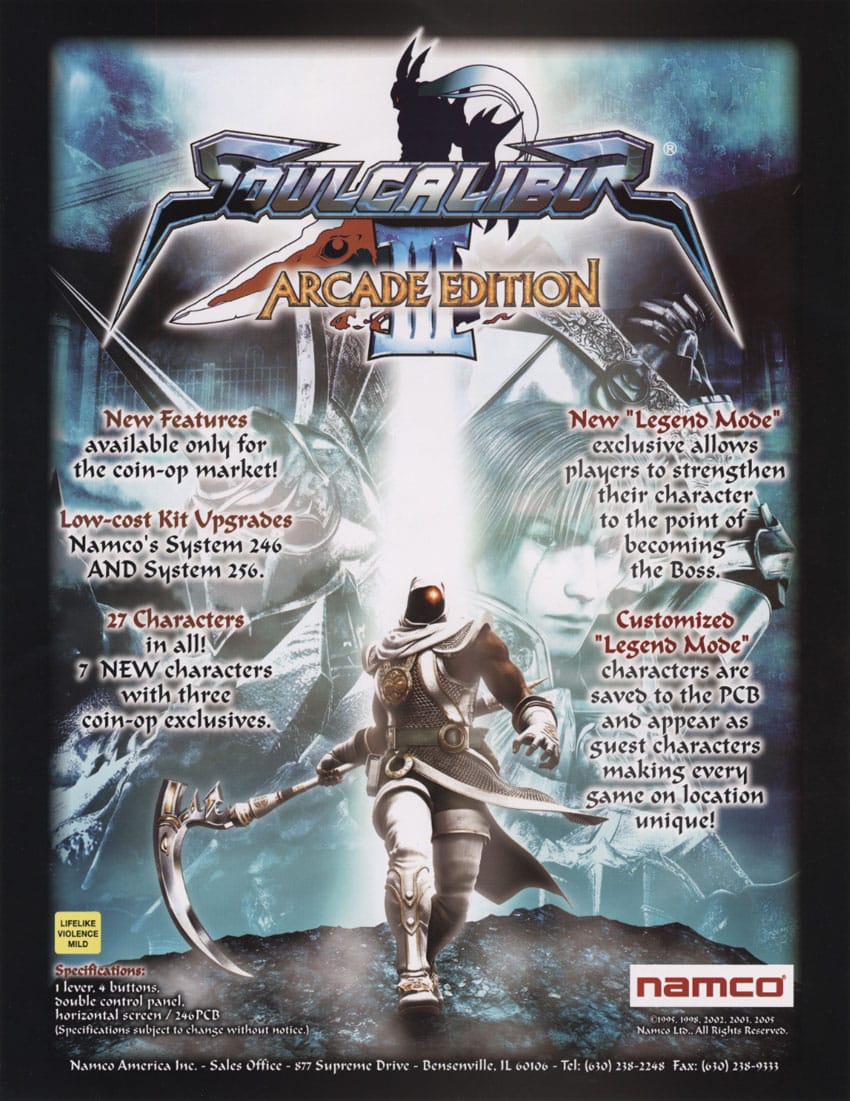

Soulcalibur III: Arcade Edition (2006)

Unlike the original Soulcalibur III, which debuted on the PlayStation 2, the Arcade Edition was a refined version built specifically for competitive play. This iteration stripped away the console’s RPG-like modes and introduced crucial balance tweaks, bug fixes, and mechanical updates aimed squarely at the arcade scene. Soulcalibur III: Arcade Edition didn’t seek to reinvent the wheel—it sharpened it.

Polished, Streamlined, and Tournament-Ready: Though less widely distributed, it became a favorite among hardcore fans who wanted a leaner, tournament-ready version of the game. The visuals remained striking, the roster was massive, and the stage designs showcased the full breadth of what the 246 could handle.

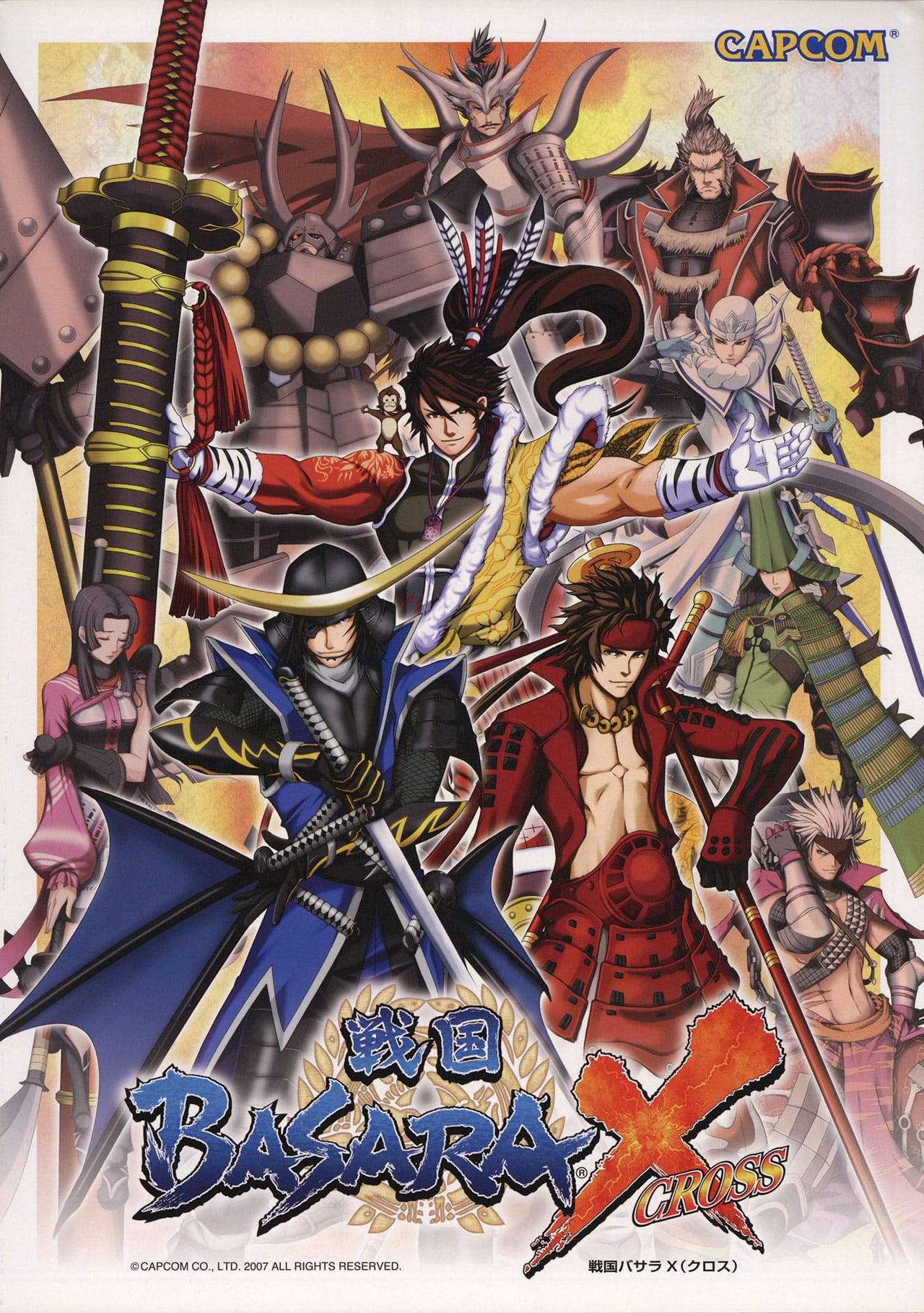

Sengoku Basara X (2008)

Co-developed with Arc System Works, Sengoku Basara X (also known as Sengoku Basara: Cross) fused Capcom’s over-the-top historical brawler series with the high-octane flair of anime-style 2D fighting. Running smoothly on the System 246, the game featured vibrant hand-drawn sprites, explosive supers, and tag-team mechanics that gave it a unique rhythm among contemporaries.

Stylish Samurai Combat: Though it never caught on competitively like Guilty Gear or BlazBlue, its visual spectacle and accessible gameplay earned it a cult following. It remains one of the 246’s most visually striking titles—a fusion of style, spectacle, and samurai swagger.

Mobile Suit Gundam: Gundam vs Gundam Next (2009)

The Gundam vs. series had already built a reputation for fast, team-based mecha combat, but Gundam vs Gundam Next took it to the next level. The System 246 (and later 256) handled the chaos with remarkable stability, enabling seamless transitions between ranged attacks, melee combos, and aerial movement. Paired with IC card progression systems and a robust competitive scene in Japan, it became one of the platform’s defining titles.

Mecha Mayhem at Its Finest: With two-on-two battles, massive mobile suits, and destructible environments, it was a love letter to Gundam fans that also delivered deep, strategic gameplay.

Honorable Mentions

While the above titles stood at the top, the System 246’s deep library also included lesser-known gems like Cobra: The Arcade (a stylish rail shooter based on the anime classic), Druaga Online (an ambitious online RPG with touchscreen controls), and Taiko no Tatsujin entries 7 through 14, which brought joy to rhythm fans through its signature drum peripherals. Each of these games highlighted the platform’s range—and reminded arcade-goers that the PS2’s second life was anything but predictable.

Console-to-Arcade Portability

In an era where arcade development was becoming increasingly expensive and risky, the Namco System 246 offered something rare: familiarity. By adopting the PlayStation 2’s architecture, Namco didn’t just future-proof their platform—they built a bridge. A bridge between living rooms and game centers. Between console dev kits and arcade cabinets. This wasn’t just a hardware decision—it was a tactical move that opened the arcade market to a broader, more diverse set of developers.

For studios already comfortable with the intricacies of PS2 hardware, the System 246 felt like home. Rather than learning new, proprietary systems with bespoke development pipelines, teams could leverage their existing PS2 engines, toolchains, and assets to build arcade versions with minimal friction. This dramatically lowered the barrier to entry, especially for console-focused studios curious about the arcade space. Games like Super Dragon Ball Z, Capcom Fighting Jam, and even Soulcalibur III: Arcade Edition all benefitted from this seamless crossover, with development cycles that were shorter, smoother, and more cost-efficient than starting from scratch.

Namco’s strategy wasn’t entirely original—but it was brilliantly executed. Sega had already laid the groundwork with its NAOMI hardware, which was based on the Dreamcast’s internal architecture. NAOMI made it easy for arcade titles to transition to consoles and vice versa, setting a compelling precedent. Namco, recognizing the same potential in the booming PlayStation 2 ecosystem, refined the idea and tailored it for their own ecosystem. The result? A platform that could host everything from experimental touch-based RPGs to polished fighting games without reinventing the wheel. It was Sega’s blueprint, but filtered through the lens of PlayStation power—and it worked.

System 246 vs the Competition

The early 2000s were a golden—and fiercely competitive—era for arcade hardware. Sega, Microsoft, and Sammy were all vying for dominance, each launching their own next-gen boards designed to capture the attention of developers and arcade operators alike. The Namco System 246 entered this battlefield with a unique advantage: the DNA of the PlayStation 2, the most developer-friendly and commercially successful console of its time. While its rivals flexed custom chipsets and cutting-edge specs, Namco focused on something far more strategic—accessibility, flexibility, and familiarity.

Sega’s Naomi 2, an evolution of their Dreamcast-based Naomi board, offered substantial power upgrades, particularly in geometry processing and multi-texturing. It was the go-to for titles like Virtua Fighter 4 and Initial D Arcade Stage, and it impressed with its ability to handle complex 3D rendering with grace. Microsoft’s Chihiro, built on the original Xbox architecture, brought blistering GPU performance and modern rendering techniques to the arcade, powering hits like OutRun 2 and Virtua Cop 3. Meanwhile, Atomiswave, developed by Sammy using Dreamcast-like tech, became a budget-friendly alternative that hosted dozens of 2D fighters and shooters, including SNK and Guilty Gear titles.

Each of these platforms had their strengths: Naomi 2’s visual power, Chihiro’s multimedia capabilities, Atomiswave’s affordability. But they also came with quirks, custom SDKs, or hardware complexities that could extend development time and inflate costs.

System 246 didn’t outgun its rivals on raw specs—but it didn’t have to. Its secret weapon was the vast ecosystem of tools, talent, and technology already built around the PS2. Developers could hit the ground running, porting assets, engines, and entire codebases with minimal rework. Familiar development environments translated to faster turnarounds, cheaper production, and greater experimentation.

For arcade operators, the 246’s modular media options (CD, DVD, HDD) and broad input support made it a versatile and cost-effective choice. And for players, it meant arcade versions of their favorite console games could feel instantly familiar while delivering the spectacle only an arcade setup could provide.

In the clash of early-2000s arcade giants, System 246 may not have been the loudest contender—but it was one of the smartest. It wasn’t about brute strength. It was about strategic alignment—and Namco played the long game with precision.

The Decline and Final Days

Like all great arcade platforms, the Namco System 246 eventually reached the end of its run. After a decade of powering genre-defining fighters, racers, and rhythm games, the aging architecture began to show its limitations. What was once cutting-edge in 2000 had, by 2011, become an elegant relic—a reminder of the time when PS2-powered cabinets ruled the floor. The sun was setting, and a new generation of hardware was waiting in the wings.

By the early 2010s, most major arcade developers had moved on to more advanced systems. Namco’s own shift to the System 357 (based on PlayStation 3 hardware) marked the official end of the 246 era. The final titles to use the platform trickled out slowly, with Taiko no Tatsujin 14 and a few regional releases closing the curtain. While support continued in some Japanese arcades for a while longer, the golden days were clearly over. After years of innovation and versatility, the System 246 quietly bowed out.

The technical ceiling had been hit. While the Emotion Engine and Graphics Synthesizer had served admirably, they were no match for the visual demands and processing needs of modern arcade games. High-definition displays, complex shaders, networked infrastructure, and massive asset libraries required far more than the 246’s aging specs could offer. Input expectations had also evolved—players demanded more from light guns, touchscreen fidelity, and latency-free online play.

Equally important, game developers were now building with HD consoles like the PS3 and Xbox 360 in mind. Platforms like Namco’s System 357 and Sega’s RingEdge series provided the horsepower and high-res support needed to match next-gen expectations. The 246, once the perfect bridge between console and arcade, had become a bottleneck.

Its retirement wasn’t a failure—it was a dignified exit for a platform that had done its job brilliantly. The Namco System 246 didn’t fade away; it passed the torch to a new era of arcade innovation, leaving behind a legacy of genre-defining games and a blueprint for console-arcade synergy that continues to influence the industry today.

Legacy and Impact

The Namco System 246 may no longer power the buzzing arcade halls of Akihabara or the dimly lit corner cabinets of your local mall, but its impact is still felt across the gaming landscape. It was a system that quietly redefined how arcade games were developed, ported, and played—leveraging console DNA to bridge two worlds at a time when that connection was anything but guaranteed. Its legacy isn’t just about hardware—it’s about influence, adaptability, and a deep catalog of unforgettable games.

By adopting console-grade architecture, the System 246 paved the way for future arcade boards to follow suit. Its success proved that familiarity and accessibility could be just as important as raw power. Namco would continue the trend with System 256 and later System 357, which transitioned to PS3 hardware. Sega mirrored this evolution with RingEdge and Nu, based on Windows PC architecture. The idea was now clear: if you want arcade developers to thrive, give them tools they already understand.

System 246 also helped normalize networked arcade experiences, persistent progression systems via IC cards, and flexible control schemes—all of which would become standard features in modern arcade platforms. Its quiet innovations laid the groundwork for the sophisticated arcade ecosystems of today.

Even now, many of the System 246’s games remain benchmarks within their genres. Soulcalibur II, Tekken 5: Dark Resurrection, and Wangan Midnight didn’t just define an era—they’ve retained active competitive scenes, fan followings, and spiritual successors. These weren’t throwaway arcade experiences. They were polished, deep, and designed to endure—often receiving home ports that brought them to an even wider audience.

There’s a reason fans still seek out Super Dragon Ball Z or get misty-eyed reminiscing about Taiko no Tatsujin 10. The 246 library was diverse, bold, and endlessly replayable. It represents a sweet spot in arcade history—where the visual jump was still impressive, and the gameplay was refined but not yet overcomplicated.

As arcade preservation becomes more vital with each passing year, System 246 has earned a place in the collector’s pantheon. Cabinets and game boards regularly trade hands among enthusiasts, particularly for rare or region-locked titles. Its modular design—with media stored on discs or HDDs—makes it slightly more accessible to maintain than older ROM-based systems.

Emulation has also entered the picture. While not as widely supported as CPS2 or Neo Geo hardware, System 246 games are slowly finding their way into the emulation community through custom setups and specialized loaders. Projects like PCSX2 have laid the groundwork, but the complexity of arcade I/O and protection schemes means the full experience is still best preserved in hardware form—for now.

Ultimately, System 246’s spirit lives on not just in the titles it hosted, but in the design philosophy it championed. It was a system for developers, for players, and for the evolving arcade industry itself. Not flashy. Not overhyped. Just quietly revolutionary.

Conclusion

The Namco System 246 wasn’t just another arcade board—it was a bold rethinking of what arcade hardware could be. By embedding PlayStation 2 architecture into its DNA, it became more than a machine—it became a bridge. A bridge between developers and players. Between console and arcade. Between tradition and evolution.

It may not have dazzled with exotic specs or flashy marketing, but its quiet brilliance lay in its versatility, accessibility, and the sheer range of unforgettable games it powered. From the refined choreography of Tekken 5: Dark Resurrection to the high-speed chaos of Wangan Midnight, the 246 was a platform where creativity could thrive without compromise.

Even today, its legacy endures—not just in collector’s circles and competitive scenes, but in the philosophy it left behind. Develop smarter. Build bridges, not barriers. Embrace hybrid thinking. These ideas still resonate in modern arcade design, console development, and even emulation.

The Namco System 246 wasn’t just part of arcade history—it helped shape its future. A PS2-powered workhorse that quietly defined a decade—and still inspires the next.