Few names in gaming conjure such a cocktail of nostalgia and audacity as Sega. Once a humble importer of coin-op amusements for postwar military bases, it transformed into an empire that electrified arcades, challenged Nintendo’s iron grip, and delivered some of the most beloved—and bizarre—experiments the industry has ever seen.

Sega was a company of contradictions: bold enough to launch Sonic the Hedgehog as a cultural counterpunch to Mario, reckless enough to flood the market with hardware add-ons, visionary enough to put online play at the heart of the Dreamcast years before broadband was commonplace.

Its story is a saga of dazzling highs and gutting lows, of creative triumphs and boardroom miscalculations, of arcade neon bleeding into the living room. To understand Sega is to understand the volatile, unrelenting energy of gaming’s golden age—a company that lived fast, burned bright, and, in many ways, still refuses to fade.

The American Seeds of a Japanese Giant

In the rubble of postwar Japan, amusement was a scarce but precious commodity. The nation was rebuilding its cities, industries, and spirit, and amid that arduous climb came a hunger for distraction. Cinemas filled with foreign films. Pachinko parlors rattled with metallic clatter. And in dim corners of smoky bars, coin-operated novelties offered a few moments of wonder for just a handful of yen. These machines weren’t mere trinkets; they were symbols of a future unshackled from austerity.

For a generation that had known only rationing and rubble, play carried an almost subversive joy. Entertainment became both escape and affirmation—proof that normal life could return, even in flickering neon and the chime of a slot payout. Into this atmosphere of fragile optimism, the amusement trade found fertile ground. From mechanical cabinets and jukeboxes to the first true arcade curiosities, Japan began to cultivate a taste for leisure imported from the West yet quickly adapted to its own sensibilities.

It all started with an opportunist and a few slot machines. Marty Bromley, a businessman with an eye for leisure, saw how U.S. servicemen stationed in Hawaii flocked to coin-operated amusements between shifts. His company, Standard Games, supplied these bases with slots and other machines that turned downtime into diversion. For soldiers far from home, they were more than games—they were a taste of normality in an unfamiliar world.

But when U.S. law cracked down on gambling equipment in military facilities, Bromley didn’t fold. Instead, he packed up his business model and looked westward. The Pacific, still reeling from the war, was becoming a new frontier for entertainment. Out of this pivot came Service Games, a venture dedicated to exporting jukeboxes, pinball tables, and slot machines to Japan. The timing was impeccable. A country eager to modernize and indulge in small pleasures welcomed these amusements, and Service Games soon became synonymous with the booming leisure trade.

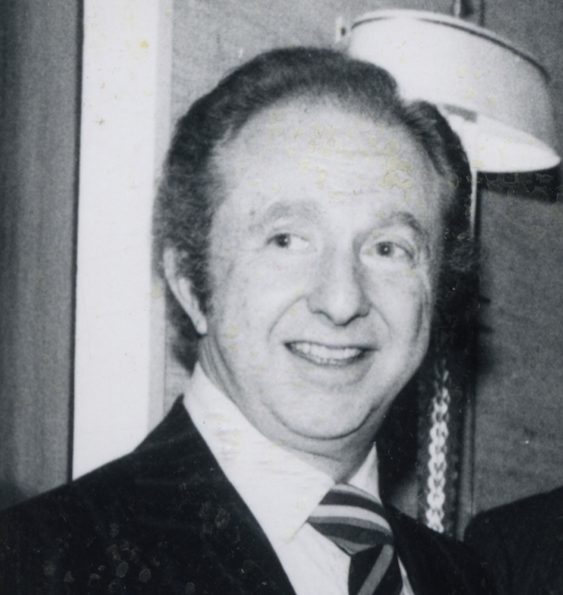

While Service Games was laying the groundwork with jukeboxes and slots, another figure was quietly carving his own path through postwar Japan. David Rosen, a young American entrepreneur, arrived in the country not with machines, but with cameras. His first business offered quick-turnaround photo portraits for occupying servicemen and local families—a small but steady trade in a nation still rebuilding its identity. It was practical, affordable, and above all, in demand.

Rosen’s knack for spotting opportunity soon pushed him further. As Japan’s appetite for convenience grew, he introduced automated photo booths that churned out ID portraits in minutes, a godsend for citizens navigating the red tape of a recovering bureaucracy. Yet Rosen wasn’t content with paperwork and passports. He had an eye for amusement, and he could see how leisure was becoming a currency of its own. By the late 1950s, his company, Rosen Enterprises, began importing arcade machines—bright, mechanical marvels that promised a few moments of joy for just a coin.

Periscope and the Birth of Sega’s Arcade Legacy

By the early ’60s, two very different strands of the amusement trade were thriving in Japan. On one side was Service Games, rooted in the pragmatic hustle of slot machines and jukeboxes, a company born from military bases and American grit. On the other was Rosen Enterprises, leaner and more creative, importing arcade amusements and cultivating Japan’s growing appetite for play. They were rivals circling the same prize: a nation ready to embrace leisure as part of everyday life.

In 1964, those paths collided. Rosen Enterprises merged with Service Games, and from the union emerged SEGA Enterprises Ltd. The name itself—short for “Service Games”—was a relic of Bromley’s world, but the new leadership would carry Rosen’s vision. What followed was a fascinating cultural blend: American-style business pragmatism meshed with Japanese craftsmanship and ingenuity. Together, they weren’t just selling machines anymore. They were laying the foundations of an entertainment empire.

This was the turning point. What began as scattered hustles in photography, slots, and arcades had coalesced into a single company with global ambition—one that would soon define how the world played.

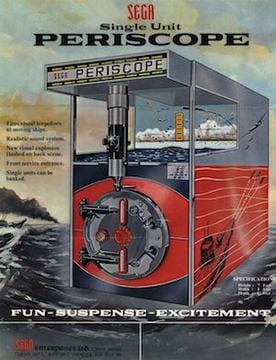

Sega’s real coming-out party didn’t happen in boardrooms—it happened in arcades, with the roar of torpedoes and the click of periscopes. In 1966, Sega unleashed Periscope, a massive electro-mechanical cabinet that put players inside a submarine, peering through a real scope to launch glowing torpedoes at illuminated ships. It wasn’t just a game; it was theater. Lights flashed, sounds boomed, and for a single coin, players were transported from bustling city streets to the depths of naval combat.

The machine was enormous, and so was its impact. In Japan, Periscope became a sensation, drawing crowds eager to try this bold new kind of entertainment. When Sega shipped it overseas, arcades in America quickly followed suit, with players lining up to experience its mix of spectacle and interactivity. More importantly, Periscope changed the math of the arcade business: at 25 cents per play, it doubled the going rate and proved that players would pay more for a premium experience.

This wasn’t just another novelty machine. Periscope marked the birth of Sega’s true arcade legacy—bold, innovative, and unafraid to bet big on entertainment that felt larger than life.

The Golden Age of Arcades

Sega had proven it could craft hits like Periscope, but scaling up required deeper pockets and global reach. Enter Gulf + Western, a sprawling American conglomerate with interests in everything from publishing to film. In 1969, it acquired Sega, giving the company both financial muscle and an international pipeline. Yet, crucially, David Rosen remained at the helm—a rare case where the visionary founder wasn’t sidelined by the corporate machine.

With backing secured, Sega began exporting joy on a grander scale. Its arcade machines weren’t just sprinkled across Tokyo and Osaka—they were shipped to Europe, North America, and beyond, introducing players from London to Los Angeles to the spectacle of Japanese entertainment engineering. Sega wasn’t merely a Japanese success story anymore; it was one of the first gaming companies to operate with a truly global mindset.

The formula was set: American capital, Japanese creativity, and a willingness to take risks that other firms avoided. This balance would propel Sega from niche amusements into an international powerhouse, setting the stage for its next great leap forward.

The 1970s cracked open a new era for play. What had once been clattering cabinets of gears and lights gave way to something sleeker, faster, and infinitely more versatile: microprocessor-powered games. This leap in technology transformed arcades from novelty parlors into cultural landmarks, humming with electronic soundtracks and neon glow. And Sega, already seasoned in spectacle, was quick to seize the moment.

Early titles like Head On (often credited with pioneering the “maze chase” formula before Pac-Man) showed Sega’s knack for finding fresh hooks. Then came Turbo, a high-octane racer that pushed speed and perspective to new heights, followed by Zaxxon, the groundbreaking isometric space shooter that stunned players with its sense of depth. Even licensed ventures like Buck Rogers: Planet of Zoom captured imaginations and helped cement Sega’s reputation as a studio unafraid to experiment with style and substance.

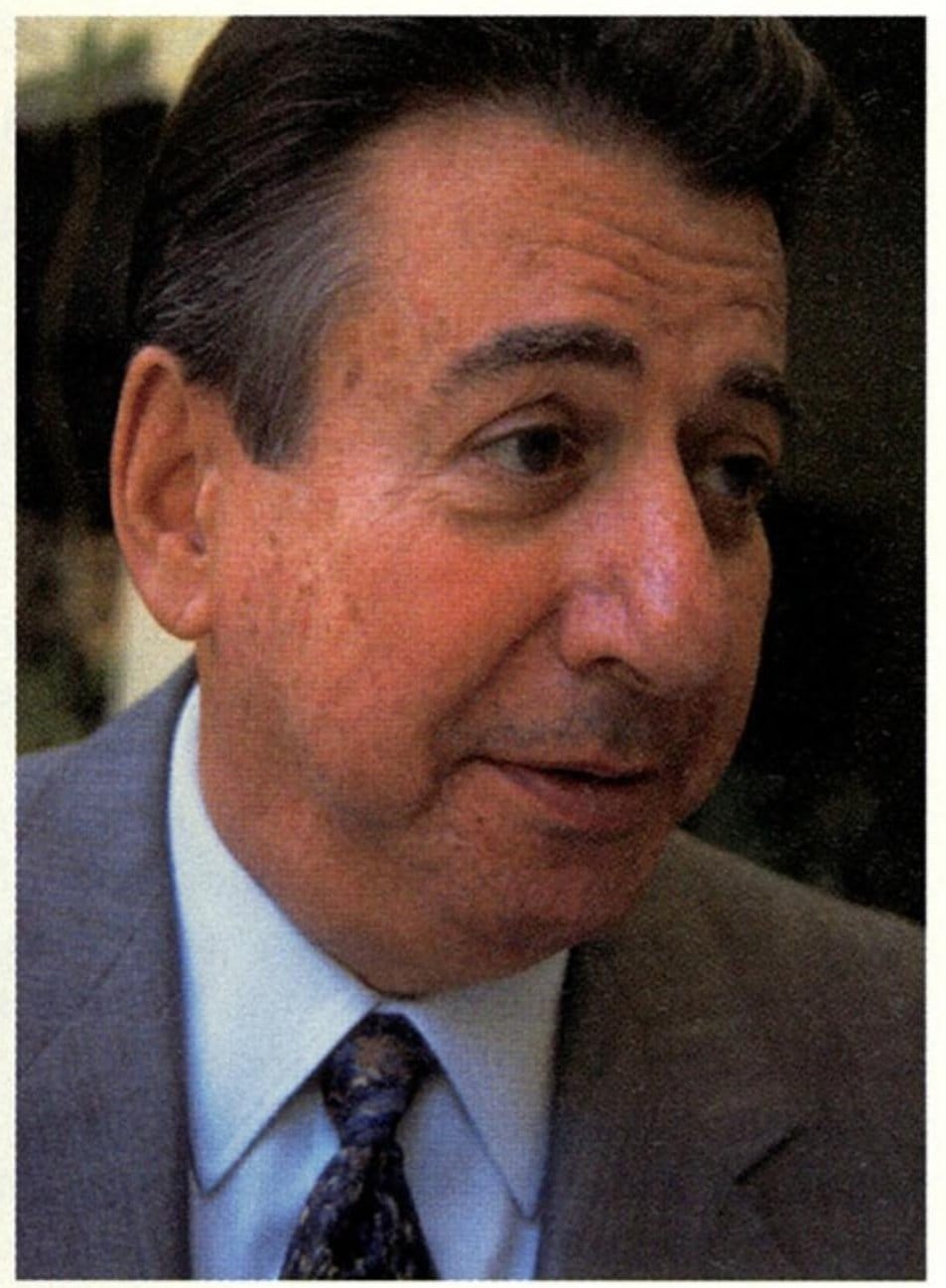

Amid this golden rush, one figure began to stand taller: Hayao Nakayama. Rising through Sega’s ranks, Nakayama wasn’t just a savvy businessman—he was a strategist with a taste for bold moves. His leadership would eventually guide Sega out of the arcades and into living rooms worldwide, where an entirely new battle for gaming supremacy awaited.

Sega’s First Foray into the Living Room

By the early 1980s, the arcade boom seemed unstoppable. Cabinets lined every pizza parlor, mall, and bowling alley, each quarter drop feeding an industry on fire. Yet beneath the flashing lights, cracks were spreading. David Rosen, ever the pragmatist, had cautioned against the industry’s reckless expansion—too many machines, too many mediocre games, and no quality control. His warnings went largely unheeded.

Then came the crash. In 1983, the American console market imploded under the weight of shovelware and consumer fatigue. This created a situation of confusion for the average customer. Each console came with its own set of games from the company that manufactured it, as well as an expansive web of third-party games. Because of this overabundance of consoles, there was little continuity throughout gaming with friends. Imagine spending hundreds on a new console and then having your friends all buy different ones.

Arcades, too, began to stumble as novelty wore thin and audiences drifted. Many small arcades were closed down due to the lack of interest in gaming. For Sega, the downturn was a brutal reality check. The golden age of arcades was over, and survival demanded a new strategy.

Out of the wreckage, however, came clarity. If arcades were waning, the future lay in the home. Both Sega and Nintendo recognized the same opportunity: households around the world were hungry for quality entertainment, but they needed trust restored. For Nintendo, this meant the NES. For Sega, it marked the beginning of a bold push into console hardware—a gamble that would define the next two decades of gaming history.

On July 15, 1983, Sega officially stepped into the living room. The SG-1000, a modest black-and-white console with interchangeable cartridges, launched in Japan on the exact same day as Nintendo’s Famicom. History would remember the Famicom as a juggernaut, but the SG-1000 was no trivial experiment. For Sega, it was proof that the company could pivot from arcade cabinets to home systems—and it laid the groundwork for bigger ambitions.

That ambition crystallized in the Mark III, later rebranded as the Master System. Technically, it was a powerhouse: sharper graphics, a broader color palette, and arcade-style performance that outclassed Nintendo’s 8-bit machine. Yet in Japan and North America, Sega faced an impossible hurdle. Nintendo’s ironclad licensing deals locked developers into exclusivity, leaving the Master System with a slimmer library and little chance to thrive.

But gaming history is rarely uniform. In Europe, where Nintendo had less presence, the Master System carved out a loyal following. In Brazil, through a partnership with TecToy, it became nothing short of a phenomenon—remaining on store shelves well into the 2000s. What began as Sega’s underdog console turned into a global sleeper success, quietly keeping the company relevant while the next great battle loomed.

16-Bit Ambition – The Mega Drive/Genesis

By the late 1980s, Sega was ready to make a statement. The company’s engineers wanted a machine that didn’t just play games—it roared with arcade DNA. The result was the Mega Drive, rechristened the Genesis in North America.

At the heart of the Mega Drive beat a processor that was practically synonymous with arcade excellence: the Motorola 68000. Used in everything from high-end computers like the Amiga to Sega’s own System 16 boards, the 68000’s speed and sophistication meant that developers could bring Sega’s arcade hits to the living room without gutting them beyond recognition. Games like Altered Beast and Golden Axe looked and played like their coin-op counterparts — something no 8-bit system could dream of achieving. In an industry where “arcade perfect” was the holy grail, the 68000 made that promise real for the first time on a home console.

This wasn’t a toy dressed up in bright plastic. The Mega Drive was sleek, black, and angular—designed to look like serious tech, the kind of hardware you’d proudly display next to your stereo. Sega’s intent was clear: this was gaming for the cool crowd, an antidote to Nintendo’s family-friendly image. And thanks to a clever design choice, it carried a subtle advantage: backward compatibility with the SG-1000 and Master System through adapters, ensuring Sega’s legacy wasn’t left behind.

On October 29, 1988, the Mega Drive hit Japanese store shelves with an aggressive price point of 21,000 yen (about $150 at the time). But Sega’s ambitions came with a catch — the Mega Drive didn’t include a pack-in game, forcing early adopters to shell out extra cash just to play.

To make matters worse, the Mega Drive’s launch came just one week after Nintendo dropped a nuclear bomb on the Japanese gaming market: Super Mario Bros. 3. Mario’s grandest adventure yet was a critical and commercial juggernaut, quickly becoming a cultural event that sucked all the air out of the room. Even Sega’s flashy new hardware couldn’t compete with the must-have magic of Mario.

As the Mega Drive was floundering in Japan, Sega knew that conquering North America — the world’s largest gaming market — was critical to their survival. In February 1989, they hired Al Nilsen as Director of Marketing for Sega of America. His first assignment? No big deal — just figure out what to call Sega’s make-or-break console in a region where “Mega Drive” was already trademarked.

Nilsen dove into market research and focus groups, juggling a shortlist of five potential names. Among the list of candidates, one name stood out like a bolt of lightning: Genesis. It was powerful, evocative, and spoke directly to the sense of transformation Sega wanted to project. This wasn’t just another console — it was a new beginning for gaming itself, a system that would shatter old expectations and usher in a bold, 16-bit future.

On August 14, 1989, the Sega Genesis stormed onto American shelves, determined to shake Nintendo’s seemingly unbreakable grip on the market. This time, Sega knew it needed more than flashy hardware specs — it needed a game that showed off the console’s raw power right out of the box. Enter Altered Beast: a thunderous, arcade-perfect brawler where players transformed into mythical creatures and unleashed pixel-crushing attacks.

The Genesis didn’t just launch another console war. It was Sega’s declaration that it could outthink and outstyle Nintendo, and for the first time, the underdog looked ready to punch above its weight.

“Genesis Does What Nintendon’t”

When the Genesis hit American shores, Sega knew raw horsepower wasn’t enough—it needed swagger. Enter the now-legendary slogan: “Genesis Does What Nintendon’t.” It wasn’t just a catchphrase; it was a gauntlet thrown straight at Nintendo’s throne. The ads were loud, brash, and rebellious, positioning the Genesis as the console for teenagers who had outgrown Mario’s candy-colored kingdoms. Sega wasn’t selling hardware—it was selling attitude.

These ads were brash, stylish, and unforgettable, hammering home the Genesis’ strengths: faster gameplay, more colors, bigger sprites, and an unbeatable arcade feel. They highlighted exclusive titles like Golden Axe, Strider, and the upcoming Sonic the Hedgehog, all while portraying the NES as yesterday’s news. The slogan became an instant classic — a rallying cry that made Sega look like the rebellious underdog everyone wanted to root for.

Where Nintendo maintained a squeaky-clean, family-friendly image with characters like Mario and Duck Hunt’s goofy dog, Sega saw an opportunity to claim an audience Nintendo largely ignored: teenagers and young adults hungry for more intense, mature experiences. Sega’s U.S. marketing campaigns emphasized fast action, aggressive themes, and arcade-like excitement, positioning the Genesis as the console for players who were ready to graduate from Saturday morning cartoons.

The campaign worked. Sega began clawing away precious market share in North America, transforming what had been a one-sided landscape into a full-scale rivalry. For the first time, Nintendo had a real challenger—and the console war was officially on. Sega wasn’t just competing; it was rewriting the rules of how a gaming company could talk to its audience.

The Sonic Boom

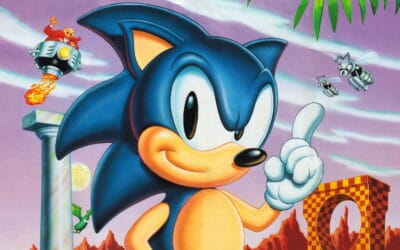

If Sega’s brash ads cracked Nintendo’s armor, Sonic the Hedgehog blew it wide open. Sonic’s creation began not as a corporate directive but as a contest launched by Sega president and CEO Hayao Nakayama. Over 100 designs were submitted, ranging from wolves to rabbits, chickens, and even humans. Naoto Ōshima—nicknamed “Big Island”—sketched many of them, with a rabbit design initially chosen for development.

The concept was handed to Yuji Naka, already celebrated for his work on Phantasy Star I and II. He built a prototype around a fast-moving rabbit that could grab and throw objects. The problem? Picking up items slowed the action down, stifling the fluid sense of speed Sega wanted. Hirokazu Yasuhara, often credited as “Carol Yas,” soon joined the project and streamlined the concept: the game should be about unbroken momentum. No gimmicks, no complicated weapons—just one button and pure velocity.

Returning to Ōshima’s sketches, the team shifted from a rabbit to a porcupine that could curl into a ball for maximum speed and attack power. They refined the design, gave him sneakers and attitude, and chose a name that captured his essence: Sonic. With that, the world’s most famous hedgehog was born.

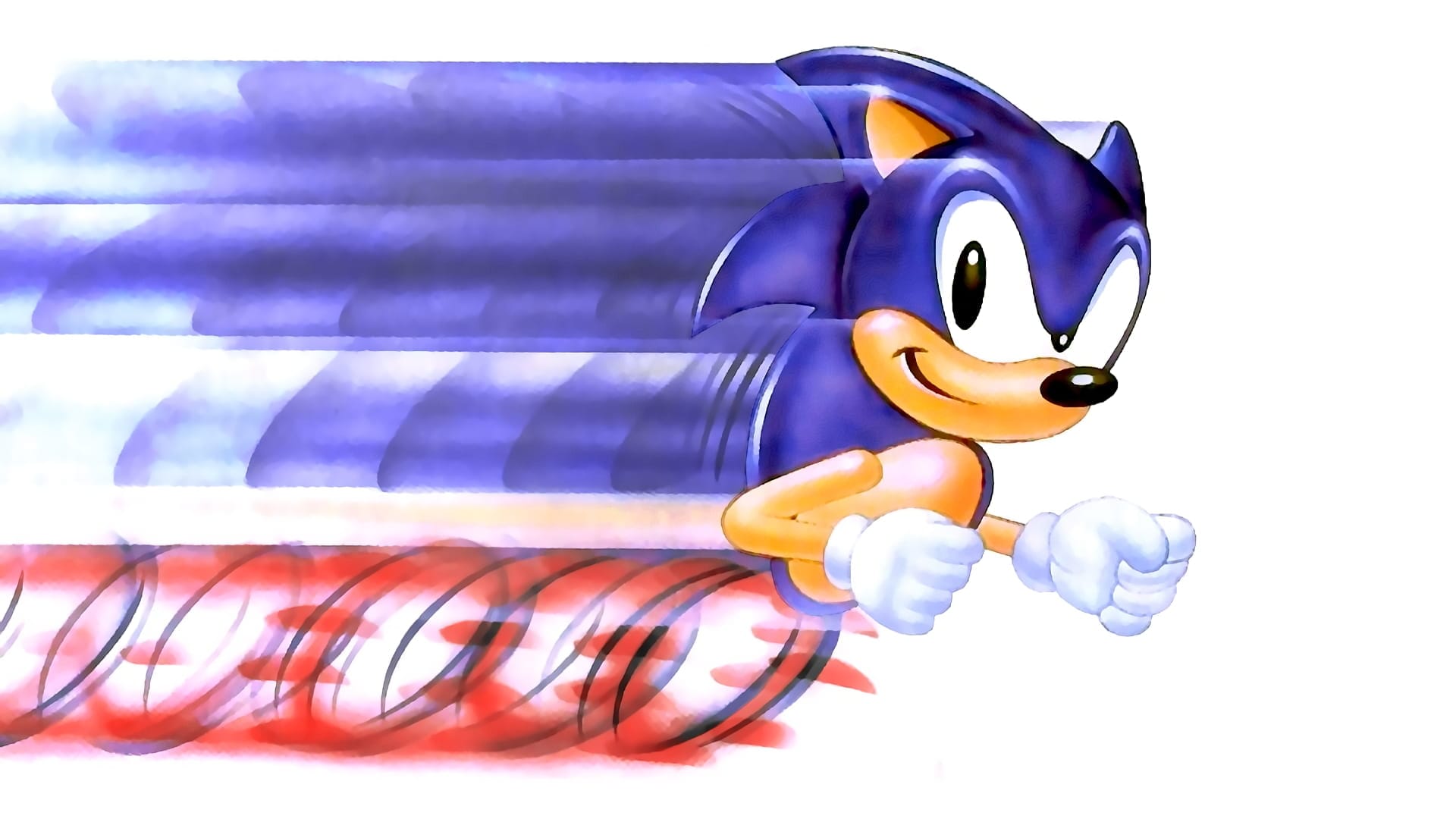

In 1991, Sonic the Hedgehog sprinted onto the Genesis and instantly became the face of a generation. Where Mario was plucky and deliberate, Sonic was sleek, fast, and irreverent—an emblem of the ’90s obsession with cool. His debut wasn’t just a success; it was a cultural detonation. Within months, Sonic became inseparable from Sega’s identity, embodying everything the Genesis promised: speed, style, and attitude.

The reception was electric. Electronic Gaming Monthly awarded Sonic a 36 out of 40 and later named it Game of the Year for 1991. GamePro gave Sonic its June 1991 cover and a near-perfect score of 24 out of 25, praising Sonic Team’s breakthrough. Sega seized the moment, plastering Sonic across magazines, television ads, and even bundling the game with the Genesis itself.

This was the era of the mascot wars, and the stakes were high. Every commercial, every magazine spread, pitted Mario and Sonic in an ideological showdown: Nintendo’s safe family fun versus Sega’s turbo-charged rebellion. Sonic’s loop-de-loops and blistering pace weren’t just gameplay mechanics—they were cultural statements.

By the early ’90s, Sonic wasn’t just Sega’s savior; he was its crown jewel. The Genesis was no longer just another console—it was the Sonic machine, a platform that had found its weapon in the fight for global dominance.

The Sega CD and 32X Gamble

Looking to widen its lead even further in the 16-bit wars, Sega of Japan engineered the Mega-CD—rebranded as the Sega CD in the States. It wasn’t even born as a gaming machine. The original plan was simply to create a cheap audio drive, but Sega pivoted, realizing that optical discs could store far more data than cartridges ever could. That extra space, they believed, was the key to bigger, better games.

When the Sega CD hit American shelves in the fall of 1992, the mood was optimistic. The add-on carried a hefty $299 price tag—twice the originally projected $150—but early adopters still bit. The hardware snapped onto the Genesis like some cybernetic upgrade and promised a future of high-capacity gaming. And in some ways, it delivered. Players got access to titles like Sonic CD, Virtua Fighter, Virtua Racing, and of course, the infamous FMV curio Night Trap. For a while, it felt like Sega had struck gold, proving that consumers really would shell out for an add-on if it offered something new.

But the honeymoon didn’t last. Beneath the promise of shiny discs lurked some very real flaws. Graphics were often grainy, load times stretched patience, and that steep price stung especially hard as whispers of “next-gen” consoles grew louder. Worst of all, the library was padded with retooled Genesis games—Mortal Kombat, Eternal Champions, Streets of Rage—that hardly justified the cost of admission.

The Sega CD burned bright, but like its overworked motors, it overheated quickly. What started as Sega’s great leap into the CD age ended up a cautionary tale: a moderate success, but ultimately a stopgap on the road to the company’s more notorious hardware missteps.

Genesis add-ons were already confusing consumers, but Sega somehow decided to double down. In a move that would baffle historians and fans alike, Sega of America went all-in on an add-on. Enter the 32X—a mushroom-shaped peripheral for the aging Genesis that promised 32-bit power at a bargain price. Released in November 1994, a little less than a month after the release of the Sega Saturn in Japan and a little less than a year from the Saturn’s American launch, the 32X was destined for failure.

On paper, it was Sega’s quick-and-dirty response to Nintendo’s FX chip and Sony’s rising threat. But in reality? It was a distraction. A detour. A desperate Hail Mary. For consumers, the message was murky at best. Sega had the Genesis. Then the Sega CD. Now the 32X. And another console—the Saturn—was just around the corner. Why invest in an expensive add-on with such a short shelf life? Why not just wait for the “real” next-gen machine? Retailers were confused. Gamers were skeptical. And the press… well, they had a field day.

Meanwhile, developers were stretched to their limits. Some were still making Genesis games. Others were tinkering with the Sega CD. Now they were being asked to support 32X and Saturn? Resources were splintered. Creativity was diluted. By trying to maintain three hardware ecosystems at once, Sega created internal chaos and external apathy.

As a result of the timing, the lack of quality games, and an awkward rollout, the 32X died on the vine. The 32X wasn’t just a mistake—it was a monument to overreach.

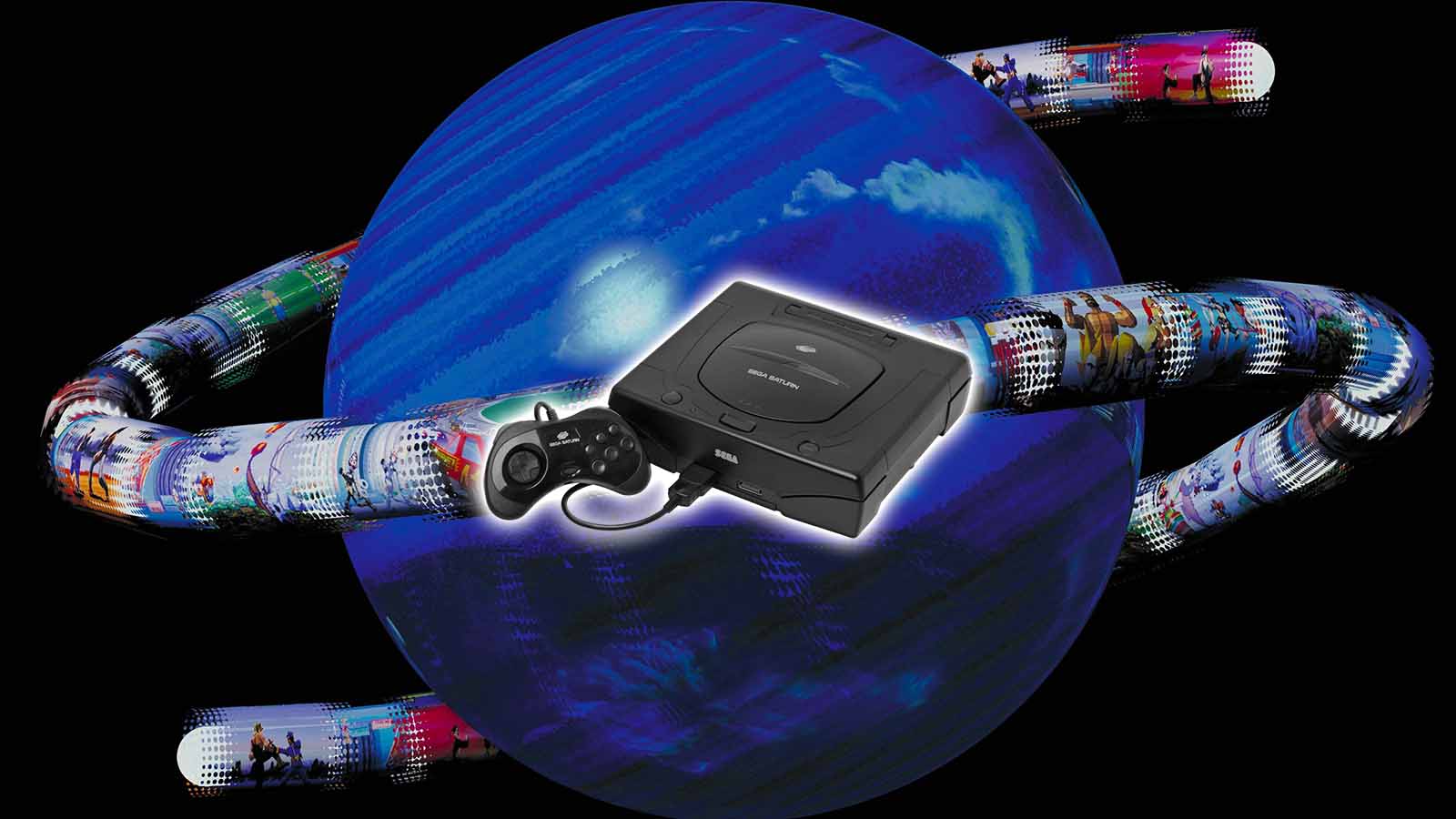

The Saturn Misfire

If the Genesis was Sega’s rebellious triumph, the Saturn was its cautionary tale. The Saturn was engineered with ambition but burdened with complexity. Sega, terrified of being outpaced by Sony’s incoming PlayStation, overdesigned the hardware—dual CPUs, multiple processors, and a labyrinthine architecture that left even veteran developers scratching their heads. Power on paper meant little when coding for the machine felt like an impossible puzzle.

The breaking point came at E3 1995. In a move meant to stun the industry, Sega announced the Saturn was available immediately—months ahead of schedule. Instead of excitement, it sparked outrage. Retailers not included in the early rollout were furious, while consumers balked at the high price and thin launch lineup. Worst of all? There was no true Sonic game to carry the system.

Meanwhile, Sony’s PlayStation arrived with swagger, a lower price, and tools that developers actually loved. The Saturn stumbled out of the gate and never recovered. For the first time, Sega looked less like a trendsetter—and more like a company that had lost the plot.

For all its horsepower and hype, the Saturn stumbled out of the gate with a launch lineup that felt more like a shrug than a statement. In North America especially, the early library lacked spark. Clockwork Knight, Bug!, and Daytona USA were decent distractions, but none of them screamed “next-gen.” Meanwhile, Sony hit the ground running with Ridge Racer, Battle Arena Toshinden, and a slicker, cooler brand identity. The Saturn’s offerings felt fragmented, like leftovers reheated from the Mega Drive era.

Then came the biggest sin: no Sonic. Sega’s blue blur was nowhere to be found. Sonic X-treme, the game that was supposed to redefine the mascot in glorious 3D, became vaporware—crushed under the weight of technical limitations, executive meddling, and infighting. Without Sonic, the Saturn lacked its flagship—its cultural shorthand. It’s hard to overstate how damaging that was.

Back in Japan, the Saturn told a different story. Titles like Sakura Wars, Radiant Silvergun, Grandia, and Shining Force III turned the system into a haven for RPG and shmup fans. But most of these masterpieces never crossed the Pacific, leaving Western audiences in the cold while Japanese players thrived.

Even when truly excellent games did arrive—Panzer Dragoon Saga, Dragon Force, Burning Rangers—they came too late. By then, the PlayStation had already won the mindshare war. By 1998, the Saturn’s library looked like a mausoleum of lost potential: brilliant, but buried.

Dreamcast – The Last Stand

By the late ’90s, Sega knew it needed a miracle. Development of the “Katana” began in 1997, with the goal of creating a cost-effective, developer-friendly console that could compete with the upcoming Sony PlayStation 2 and solidify Sega’s place in the market. To achieve an affordable console, Sega opted for off-the-shelf components, reducing production costs and making development easier.

Another key design decision was the use of a custom version of Windows CE, a move intended to make porting PC games easier and attract developers who were hesitant after Sega’s past failures. While these specifications at the time were cutting-edge, not everyone at Sega were happy about these choices.

When looking for hardware for the new Sega console nicknamed “Dural” (which was later called “Katana”), Sega’s Japanese and US executives were in a disagreement over which hardware to choose. But in the end, the Japanese executives won the battle, and chose the Japanese NEC PowerVR graphics over the American 3dfx Voodoo graphics. Little did they know how much problems this dispute would cause in the future.

Sega officially unveiled the Dreamcast on May 21, 1998, in Tokyo, setting the stage for its comeback. To engage fans, Sega held a public competition to name the console, ultimately settling on “Dreamcast”—a fusion of “Dream” and “Broadcast.” The name reflected the console’s ambition to deliver groundbreaking entertainment and online connectivity.

The VMU, a quirky memory card with its own screen, turned saves and mini-games into pocket-sized novelties. Built-in modem support meant online play was finally a reality, years before broadband became standard. And graphically, the Dreamcast delivered arcade perfection straight to the living room.

Sega doubled down on marketing, with one of the most memorable campaigns in gaming history—the cryptic “It’s Thinking” ads in North America. These eerie, futuristic commercials hinted at the Dreamcast’s advanced AI and innovative features, aiming to build intrigue and excitement.

Additionally, Sega partnered with Hollywood Video for a pre-launch rental program, allowing players to test the console before its official release. This strategy gave potential buyers hands-on experience, helping to build confidence and anticipation for the Dreamcast’s arrival.

For a brief, brilliant moment, it worked. Launch day in 1999 saw record-breaking sales in the U.S., and Sega’s underdog machine won over a passionate fanbase. Yet storm clouds loomed. Sony’s PlayStation 2 was waiting in the wings, promising not just cutting-edge games, but also DVD playback—a killer feature at the dawn of the home movie boom.

Publishers, wary of Sega’s recent missteps, shifted their bets to Sony. The Dreamcast, despite its innovation and devoted following, couldn’t outrun the tidal wave. By 2001, Sega bowed out of the hardware race, leaving the Dreamcast as both a swan song and a symbol of what could have been.

By 2001, the writing was on the wall. The Dreamcast—brilliant, beloved, but battered—was Sega’s final throw of the dice in the console wars. Despite its innovations, it couldn’t withstand the looming shadow of the PlayStation 2 and the tectonic shifts in the industry. On January 31, 2001, Sega announced the unthinkable: it was leaving the hardware business.

For a company that had built its identity on consoles—on battling Nintendo, Sony, and anyone else brave enough to enter the ring—the decision felt like both a tragedy and an inevitability. But Sega wasn’t finished. The company pivoted, channeling its arcade DNA and creative energy into third-party publishing. Suddenly, Sonic was spinning onto Nintendo’s GameCube, and other Sega’s franchises were migrating across platforms that once were rivals.

If the Dreamcast’s death marked the end of Sega as a console maker, it also marked the beginning of Sega’s rebirth as a software powerhouse. The company’s legacy wasn’t bound to hardware anymore—it lived on through characters, worlds, and franchises that still define gaming decades later.

Sega’s Most Iconic Games

Some of these games rewrote rulebooks. Others carved out cult legacies that still pulse through modern design. All of them left fingerprints on the medium. This is a look back at the games that defined SEGA at its boldest, strangest, and most unforgettable.

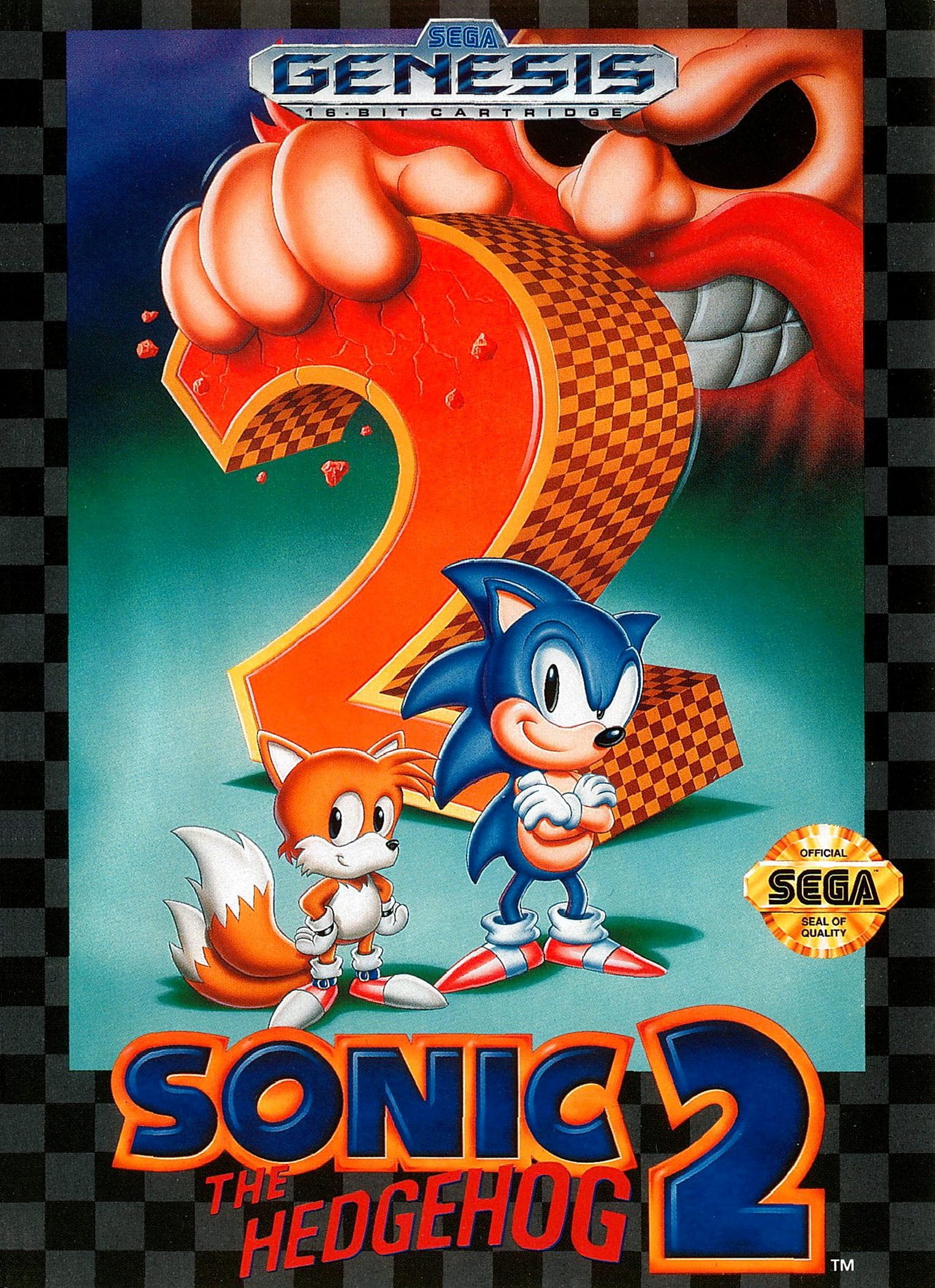

Sonic the Hedgehog 2 (1992)

A Sequel Done Right: Everything about Sonic the Hedgehog 2 feels more assured, more muscular, more alive. The addition of Tails softened the edges just enough to widen Sonic’s appeal without sanding off the attitude. Packed with split paths, hidden vertical routes, and risk-reward decisions that never make you slow down, Sonic 2 delivers a sensation few platformers can match.

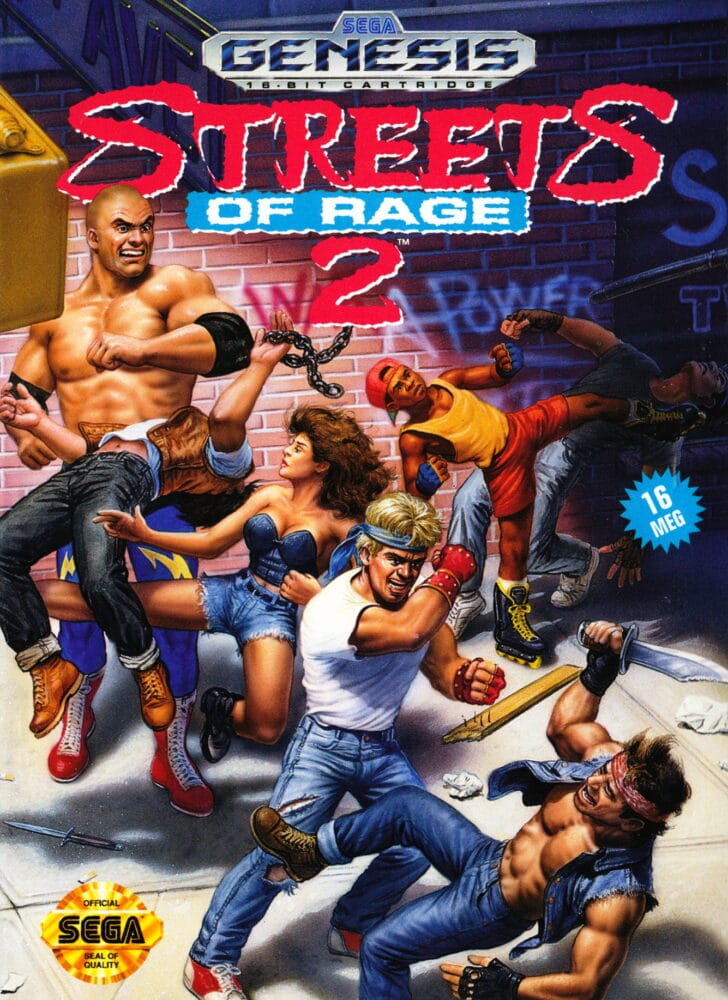

Streets of Rage 2 (1992)

The Legendary Beat-’em-Up: Streets of Rage 2 is the moment the beat-’em-up genre hit its absolute stride. Punches snap with weight, and every encounter feels deliberate, demanding awareness rather than blind button mashing. Featuring Yuzo Koshiro’s legendary electronic score, Streets of Rage 2 still hits hard decades after its release.

Shinobi III: Return of the Ninja Master (1993)

Ninja Artistry In Motion: Shinobi III makes you feel like a true ninja navigating a world that tests your reflexes and wits. With every jump, dash, and sword slash flowing seamlessly, Joe Musashi moves in a way that almost feels modern. With a demanding but fair difficulty, Shinobi III provides a sense of challenge that rewards confidence and skill in equal measure.

Virtua Fighter 2 (1994)

Technical Brilliance: Virtua Fighter 2 was a game-changer the moment it hit arcades. Throws, counters, and strikes all operate on a logic that rewards strategy over button-mashing chaos. Suddenly, fighting games weren’t just flat stages with sprites—they were fully realized 3D arenas where spacing, timing, and movement mattered like never before.

Daytona USA (1994)

Pure Arcade Adrenaline: Daytona USA was a celebration of arcade thrills. From the moment the engine roars and the music kicks in, you’re hooked. You can feel the tires gripping the track, and every drift is a delicate dance between control and chaos. It’s competitive, chaotic, and endlessly replayable, the kind of experience that makes you lean into the screen and scream at your rivals.

Sega Rally Championship (1994)

Drifting, Dirt, and Realism: Long before modern simulators made realism a buzzword, SEGA captured the feel of driving through mud, gravel, and tarmac with uncanny finesse. The cars don’t just turn—they bite, slide, and fight back, responding like a real machine. Even decades later, its blend of skill and accessibility keeps it at the top of arcade racing classics.

NiGHTS into Dreams… (1996)

SEGA’s Imagination at Full Display: NiGHTS into Dreams... feels like stepping inside someone else’s imagination—and that’s exactly the point. Levels spiral, float, and stretch in ways that make the impossible feel natural, creating a sense of flight that’s simultaneously exhilarating and meditative.It’s softer, stranger, and yet undeniably SEGA—a game that invites you to lose yourself, dream after dream.

Panzer Dragoon Saga (1998)

Saturn’s Finest RPG: Set in a post-apocalyptic landscape that’s both haunting and beautiful, Panzer Dragoon Saga drips with personality. Timing your shots, managing your dragon’s abilities, and reading enemy patterns turns each encounter into a strategic ballet. Blending cinematic presentation, deep storytelling, and innovative gameplay, it’s one of the most unforgettable journeys in RPG history.

Sonic Adventure (1998)

Sonic’s Leap Into The Third Dimension: Sonic Adventure redefined what a 3D platformer could be, making every level an unforgettable experience. Sonic wasn’t just running anymore; he was racing through a world that felt alive, vertical, and bursting with secrets. With adrenaline pumping music, visuals that pop with color, and a story that gives Sonic a surprisingly human edge, Sonic Adventure is a defining moment for the franchise.

Space Channel 5 (1999)

Rhythm, Fashion, and Futuristic Pop Energy: Space Channel 5 is a rhythm game unlike any other. From the moment you step into Ulala’s platform shoes, you’re thrust into a universe where every beat matters, every pose counts, and every enemy confrontation feels like a dance-off straight out of a retro-futuristic music video. It’s proof that SEGA could take risks and still create a game that’s incredibly fun.

Shenmue (1999)

Open-World Ambition: Shenmue is the kind of game that makes you stop and notice the little things. Long before “open-world” was a marketing term, it blended combat, exploration, and mini-games fluidly into daily life. Shenmue dared to be human, detailed, and deliberate, proving that a game could prioritize atmosphere without sacrificing authenticity.

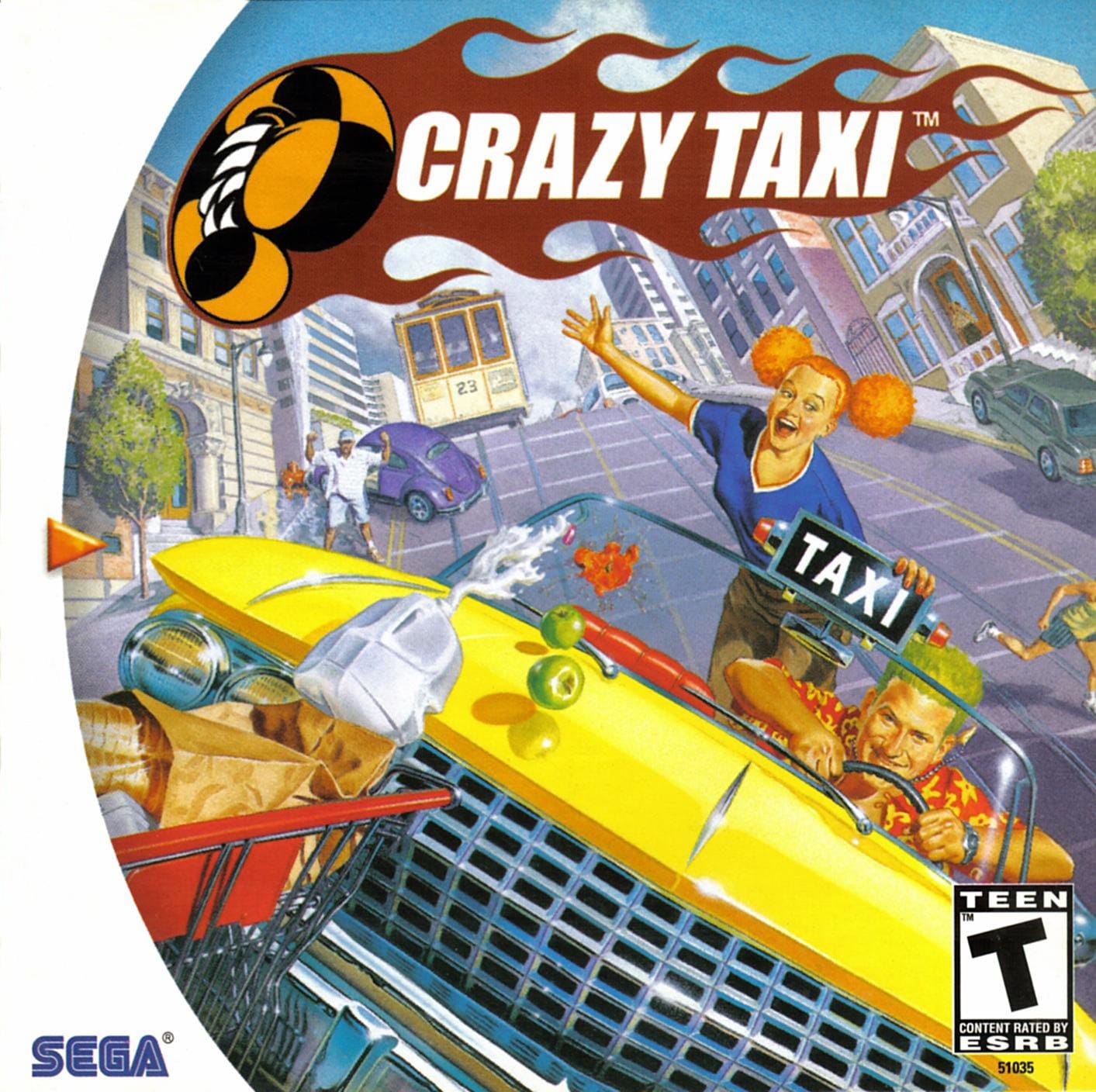

Crazy Taxi (1999)

Punk Rock Arcade Chaos: Crazy Taxi throws you into a city that feels alive, untamed, and entirely your playground. Every passenger, every intersection, every ramp becomes an opportunity to chain together insane combos, earn outrageous tips, and scrape past disaster by the thinnest margin. Infused with a punk-rock soundtrack featuring The Offspring, Crazy Taxi is wild, brash, and still delivers the same rush it did at arcades and consoles.

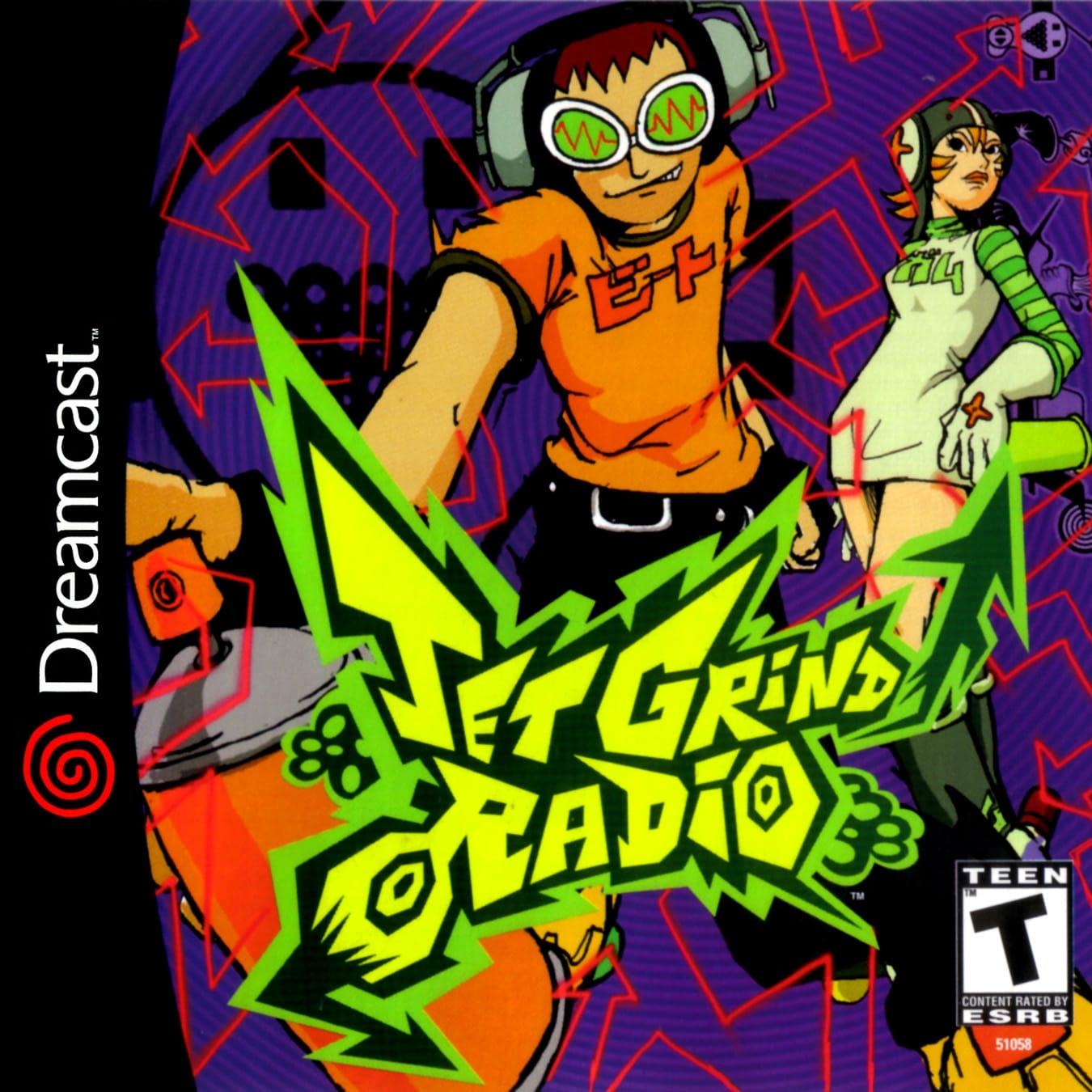

Jet Set Radio (2000)

Street Art and Cel-Shaded Swagger: Jet Set Radio blends graffiti art, music, and gameplay into something wholly unique. Skating, jumping, and grinding all feel connected, and tagging territory is about strategy, timing, and claiming your mark against rival gangs. With a pulsating mix of J-pop, hip-hop, and electronic beats, Jet Set Radio proves SEGA could make fun games with attitude.

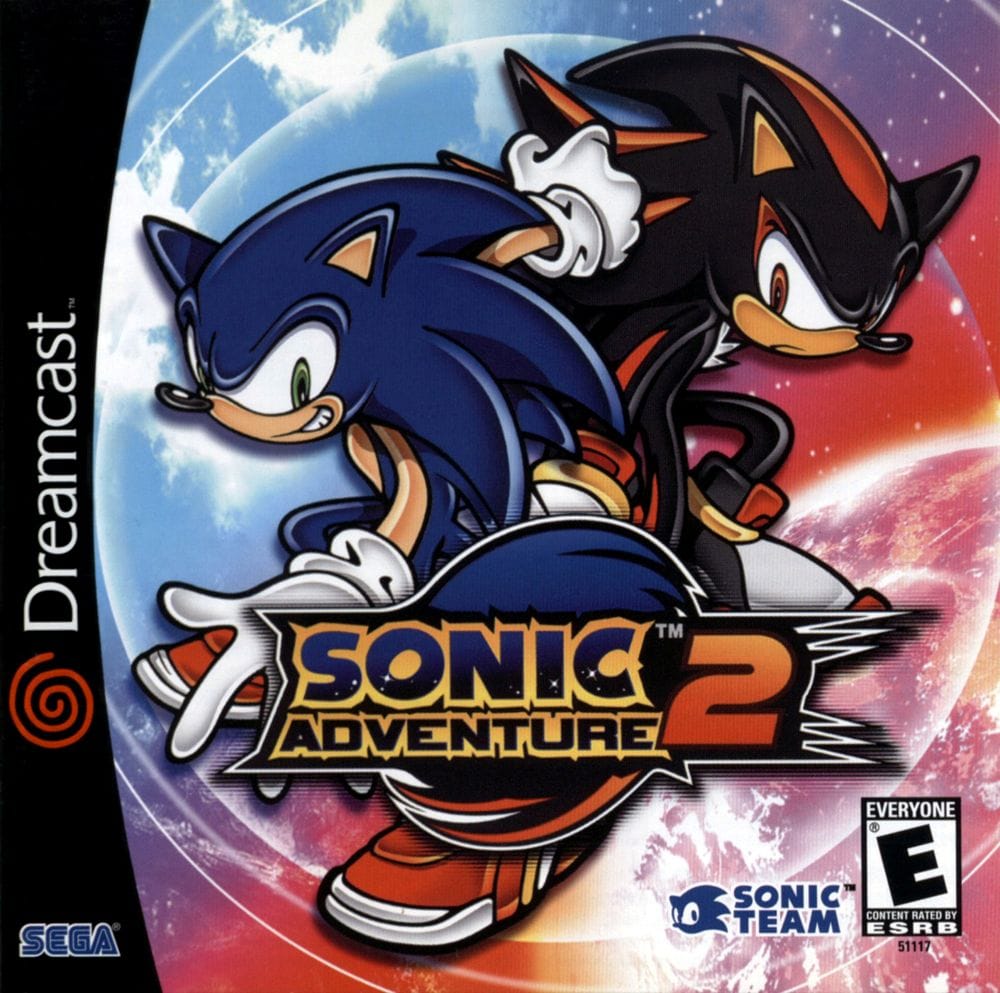

Sonic Adventure 2 (2001)

Sonic At His 3D Peak: Sonic Adventure 2 is where SEGA took everything that worked in Sonic’s first 3D outing and sharpened it to a razor edge. The controls are tighter, the pacing is faster, and the level design feels more confident than ever before. With the introduction of Shadow adds a compelling rivalry to the story, and it’s easy to see why so many fans still hold Sonic Adventure 2 to high regard.

Sega’s Lasting Legacy

After exiting the hardware business, Sega didn’t fade quietly—it doubled down on making games. Super Monkey Ball, Virtua Fighter, and Shinobi kept the Sega spirit alive. Phantasy Star bridged the gap between Western-style sci-fi and Japanese RPG storytelling, while Virtua Fighter turned fighting games into 3D arenas of precision.

Sonic became more than a mascot; he was Sega’s rebellion in blue sneakers. The once-bitter rivals even became unlikely teammates, as Sonic showed up in Super Smash Bros. and headlined the Mario and Sonic at the Olympic Games series. And then came Hollywood. The Sonic the Hedgehog movies stormed box offices worldwide, smashing past $1 billion globally and reintroducing Sega’s mascot to an entirely new generation of kids. For Sega, that surge of cultural relevance was more than nostalgia—it was survival.

Sega still matters because it taught the industry to take risks. From pioneering online play to blurring the line between arcade spectacle and home entertainment, Sega never stopped chasing the next big idea—even when the gamble didn’t pay off. That restless spirit continues today in its games, its characters, and its cult-like following. The consoles may be gone, but the dream—wild, inventive, and just a little unruly—still lives on.