The early ’90s were a battlefield. Not just for gamers clutching their controllers, but for the titans behind the screens—Sega and Nintendo—each lobbing cartridges and innovation like artillery. The fourth generation console war wasn’t a scuffle. It was an era-defining showdown. On one side, Nintendo’s stoic Super Nintendo, a machine of polish and technical grace. On the other, Sega’s rambunctious Genesis, swaggering with ‘Blast Processing’ and attitude to spare.

As the fifth generation loomed, Sega smelled blood. Nintendo’s N64 was delayed. Sony’s PlayStation was still shrouded in mystery. The path was open. Sega could strike first. Could win. But instead of a triumphant return, the Sega Saturn would spiral into confusion, internal warfare, and missed opportunity. What went wrong? And how did Sega, once riding high, fall so hard when the throne was within reach?

The Birth of the Sega Saturn

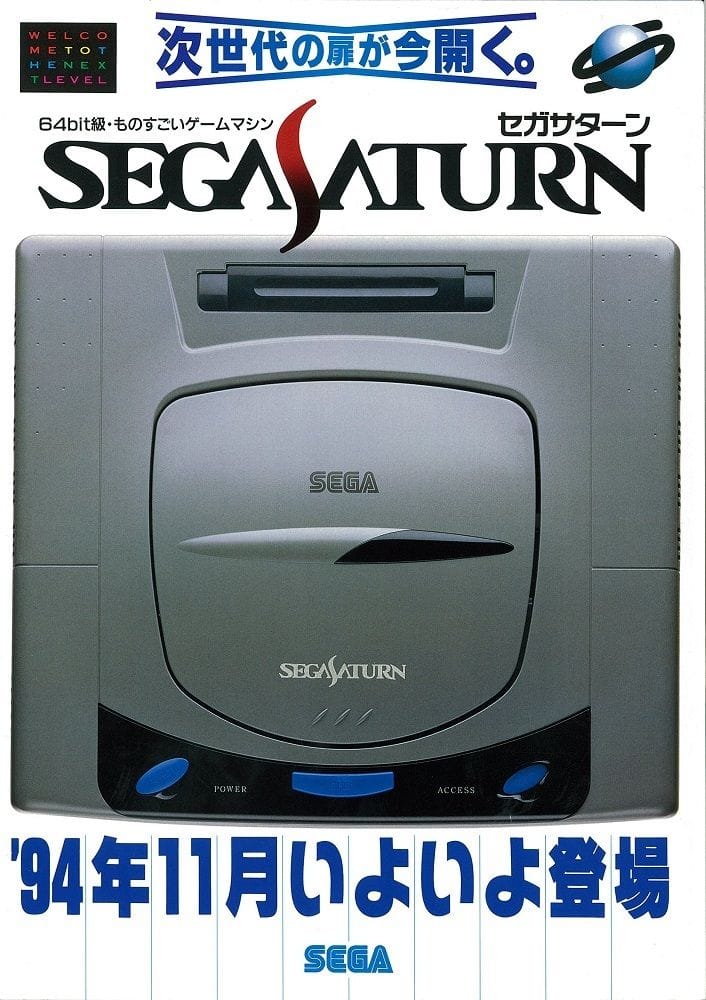

By 1991, murmurs were already swirling through Tokyo boardrooms and developer dens. Nintendo’s Super Famicom had landed in Japan like a thunderclap, and while the Genesis was still duking it out with the SNES in the West, Sega’s leadership in Japan saw the writing on the wall. The next wave was coming. If the company wanted to truly leapfrog its rivals, it had to start laying the foundation for the next generation right away.

Internally, Sega kicked off a secretive campaign. A skunkworks team of 27 engineers, designers, and dreamers, led by the brilliant Hideki Sato—father of the Mega Drive—was assembled to begin crafting Sega’s next flagship. The goal? To create a CD-based system powerful enough to propel the company into the future of gaming. At a time when the cartridge was still king, this was a bold statement.

Dubbed “Project Saturn,” the console was envisioned as a no-compromise machine. It would embrace the rising potential of CD-ROMs, promising more storage, bigger games, richer audio, and cinematic cutscenes that cartridges couldn’t dream of. Sega was swinging for the fences—and on paper, it looked like a home run.

For nearly two years, this team labored in near-total secrecy. They worked through endless prototypes, chip configurations, and speculative features, trying to stay one step ahead of Nintendo while also anticipating the demands of developers who would one day have to build games for the platform.

To truly leap into the fifth generation, Sega knew it couldn’t go it alone. The company needed partners with deep technical expertise to bring its ambitious vision to life, and few names carried more weight in Japan’s electronics scene than Hitachi. By aligning with Hitachi, the Saturn could harness cutting-edge silicon while taking advantage of the format shift that was reshaping entertainment as a whole.

Industry speculation ran wild, with many assuming it would be a 32-bit system that relied on CDs, possibly with some backward compatibility for Mega Drive owners. Meanwhile, Sega teased its vision indirectly through the arcades—games like Virtua Racing and Virtua Fighter hinted at a tantalizing 3D future.

For a moment, everything seemed to be aligning. Sega had the hardware brains of Hitachi, the allure of CD technology, and the swagger of a company that had just gone toe-to-toe with Nintendo. On paper, the Saturn looked unstoppable. But what gleamed as innovation in the lab would soon reveal itself as something far more complicated once the console reached the hands of developers.

From 2D Powerhouse to 3D Contender

When work on the Saturn first began, Sega wasn’t imagining a polygonal future. The original goal was straightforward: build the ultimate 2D machine. At the time, 2D graphics were still king. Arcades thrived on fighting games and sprite-heavy shooters, and Sega believed the next big console would dominate by delivering those experiences flawlessly at home.

The Saturn’s early blueprints reflected that philosophy. Its architecture was loaded with custom chips designed to push sprites, layers, and parallax scrolling to unprecedented levels of detail. Background rendering, sprite handling, and texture work were carefully divided across multiple processors, giving developers theoretical precision and power when crafting 2D masterpieces. Sega envisioned arcade-perfect conversions of its biggest hits, from Street Fighter rivals to bullet-hell shooters, and a new wave of titles that would leave the Super Nintendo looking positively archaic.

It made sense at the time, but nobody could have predicted just how quickly the winds were about to shift. In 1993, Namco unveiled Ridge Racer at the Amusement Machine Show in Japan, a fully 3D racing game running on cutting-edge arcade hardware. It wasn’t just impressive—it was a revelation. Where Sega had been perfecting pixel art and sprite scaling, Namco was showing a future where textured polygons screamed across the screen with fluidity and style.

The demo landed like a thunderclap. Players crowded around cabinets to witness cars rendered in smooth 3D, hugging corners and darting through tunnels with a sense of depth that 2D could never match. Suddenly, the old model of “bigger sprites and more colors” looked outdated. The industry’s center of gravity was shifting, and it was happening faster than anyone anticipated.

For Sega, the impact was immediate and sobering. The Saturn, still in development as a 2D powerhouse, now looked dangerously out of step with the emerging zeitgeist. If Ridge Racer represented where gaming was headed, Sega’s next console risked being obsolete before it even hit store shelves.

Panic—or perhaps pragmatism—set in. Sega began retooling the Saturn’s design, adding additional processors to give it the polygon-pushing muscle it desperately needed. The pivot was bold, but it came at a cost: complexity. The Saturn was no longer a streamlined 2D juggernaut. It was morphing into something far more unwieldy—a console that could, in theory, compete in the 3D race, but only if developers could figure out how to harness its newfound power.

A Developer’s Nightmare

On paper, the Sega Saturn looked like a revelation. Dual Hitachi SH-2 processors, running in tandem, offered serious muscle—at least in theory. These twin CPUs could handle parallel tasks with blazing efficiency. But there was a catch. Developers had to write code that perfectly synchronized both chips. And unless your studio was staffed with NASA-grade engineers, you were in for a brutal time. Mismanage the SH-2s, and performance tanked. Theoretically powerful? Absolutely. Practically useful? Rarely.

Then came the dual video display processors—VDP1 and VDP2. VDP1 was built to render sprites, polygons, and textures. VDP2 handled backgrounds and scrolling planes. It sounded elegant. Instead, it became an exercise in controlled chaos. Splitting visual duties across two processors demanded precision most studios couldn’t afford. Get it right, and the Saturn delivered lush, multi-layered visuals. Get it wrong, and it looked like a jammed arcade cabinet.

Add to this an SH-1 processor dedicated purely to CD-ROM control. Toss in a Yamaha-powered custom sound chip, paired with a Motorola 68EC000 for good measure. It had 32 audio channels. FM synthesis. 16-bit PCM sampling. A soundscape beast. But who could tame it all?

Technically, the Saturn could outgun the PlayStation in sheer specs—140,000 textured polygons per second versus Sony’s 90,000. But Sony’s machine had a unified, developer-friendly design. Saturn had raw power locked behind an instruction manual no one wanted to read. A beast, yes—but one locked in its own cage.

“What they are saying is that Sega has spent the last nine months or so playing catch-up with Sony after a publisher-friend tipped Sega off about the power of PlayStation. New specs and development tools only recently arrived with third parties, superseding Sega’s original description of the project. The main difference between them is apparently the addition of more dedicated processors taking work away from the two CPUs.”

- Next Generation Vol. 1

In theory, splitting tasks across two CPUs sounds like a clever way to double your horsepower. In practice, it was like conducting an orchestra with two batons and no sheet music. Developers had to assign specific jobs—AI, rendering, physics, audio—to each SH-2 chip with surgical precision. But without proper documentation or tooling, this became a guessing game of trial and error. And even when it worked, squeezing performance out of the Saturn felt like wringing water from a stone.

Third-party developers? They were left out in the cold. By the time many studios received proper dev kits, Sony had already handed out sleek PlayStation tools with polished documentation and robust support. Saturn’s kits arrived late—and when they did, they were complicated, unfinished, and sometimes barely usable. Smaller studios, especially in the West, didn’t stand a chance. Why battle with Saturn’s labyrinthine internals when PlayStation development felt like plug-and-play?

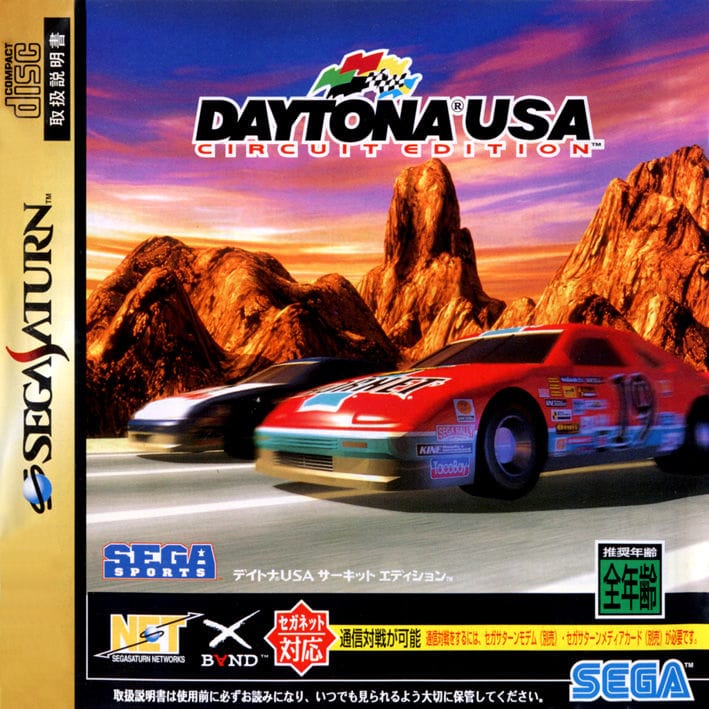

Even Sega’s elite internal teams struggled at first. AM2—yes, the same gods behind Virtua Fighter—had difficulty translating their arcade magic onto Saturn hardware. Ports of games like Daytona USA and Virtua Fighter launched looking jagged and rushed. If Sega’s own masterminds were grappling with the system’s complexity, what hope did anyone else have?

Two Systems Too Many: The 32X Fiasco

In a move that would baffle historians and fans alike, Sega of America decided to go all-in on an add-on. Enter the 32X—a mushroom-shaped peripheral for the aging Genesis that promised 32-bit power at a bargain price. On paper, it was Sega’s quick-and-dirty response to Nintendo’s FX chip and Sony’s rising threat. But in reality? It was a distraction. A detour. A desperate Hail Mary.

Internally, the timing couldn’t have been worse. Both the 32X and Saturn relied on the same Hitachi SH-2 chips. But there weren’t enough to go around. With the Saturn nearing its Japanese launch window, Sega of Japan hoarded the lion’s share of the chips. That left the 32X scrambling for scraps, resulting in production bottlenecks and delays before it even hit store shelves.

For consumers, the message was murky at best. Sega had the Genesis. Then the Sega CD. Now the 32X. And another console—Saturn—was just around the corner. Why invest in an expensive add-on with such a short shelf life? Why not just wait for the “real” next-gen machine? Retailers were confused. Gamers were skeptical. And the press… well, they had a field day.

Meanwhile, developers were stretched to their limits. Some were still making Genesis games. Others were tinkering with Sega CD. Now they were being asked to support 32X and Saturn? Resources were splintered. Creativity was diluted. By trying to maintain three hardware ecosystems at once, Sega created internal chaos and external apathy. The 32X wasn’t just a mistake—it was a monument to overreach.

The Launch Heard Around the World (For the Wrong Reasons)

In November 1994, Sega of Japan pulled the trigger on the Saturn’s release. The launch was sudden, almost audacious—stores were stocked, ads were running, and the console was available before many developers were ready. It was a move designed to stake a claim in the next generation before Sony’s PlayStation could even flex its muscles. But while Japan raced ahead, the American branch was stuck in a very different struggle: the 32X.

Sega of America had invested heavily in the 32X, a mid-generation add-on for the Genesis meant to extend its life and fend off Nintendo’s advances. The system was plagued by tight deadlines, component shortages, and a glaring identity problem—why buy a 32X when the Saturn was just around the corner? Meanwhile, Japan’s focus on the Saturn siphoned resources, making it harder for the U.S. team to deliver a coherent marketing or supply strategy.

The result was confusion on both sides of the Pacific. Japanese consumers got a sophisticated, albeit complex, machine before its software library was fully ready. American gamers were confronted with two conflicting products—the aging Genesis with its 32X add-on and the tantalizing promise of the Saturn just months away. Retailers didn’t know what to stock, developers didn’t know where to invest, and consumers didn’t know which system deserved their attention.

Then came the North American launch—a case study in how not to introduce a console. The infamous E3 1995 reveal saw Sega pull the trigger early, unleashing the Saturn onto store shelves months ahead of schedule. Except… not all shelves. Retail partners like Walmart and KB Toys, blindsided by the move, were excluded from the initial rollout. Many were livid. Some retaliated by refusing to carry the system entirely.

The strategy was bold, even reckless. Sega wanted to grab the headlines and establish a head start over Sony’s PlayStation, which was still weeks from its U.S. debut. The hope was that early availability would translate into sales momentum, a strong foothold before Sony could make its mark. But the execution backfired spectacularly. Retailers hadn’t stocked enough units, and third-party developers weren’t ready with launch titles. What was intended as a tactical advantage turned into chaos.

Sony, in contrast, only needed three words to change the entire landscape: “Two ninety-nine.” With that effortless mic drop at E3 1995, Sony did more than undercut Sega—they redefined cool. The Saturn’s $399 price tag suddenly looked bloated, antiquated, and out of touch. While Sega’s “surprise” made waves in the short term, it also sowed confusion and frustration that lingered long after the show floor lights dimmed. The event became legendary—not for boosting Saturn sales, but for illustrating the missteps that would plague the console throughout its life.

The PlayStation Factor

By the time the Saturn stumbled out of the gate, Sony was quietly orchestrating a masterclass in console launch strategy. The PlayStation arrived with a trifecta of advantages: a sleek, modern design that looked and felt cutting-edge, hardware that developers could actually understand and exploit, and a price point aggressive enough to make early adopters take notice without hesitation.

Where Saturn’s dual CPUs and complex VDP setup had developers scratching their heads, the PlayStation offered simplicity without sacrificing power. Studios could tap into 3D graphics with relative ease, leading to rapid, high-quality software output. This accessibility turned Sony into an instant favorite among third parties, who quickly prioritized PlayStation titles over Saturn projects.

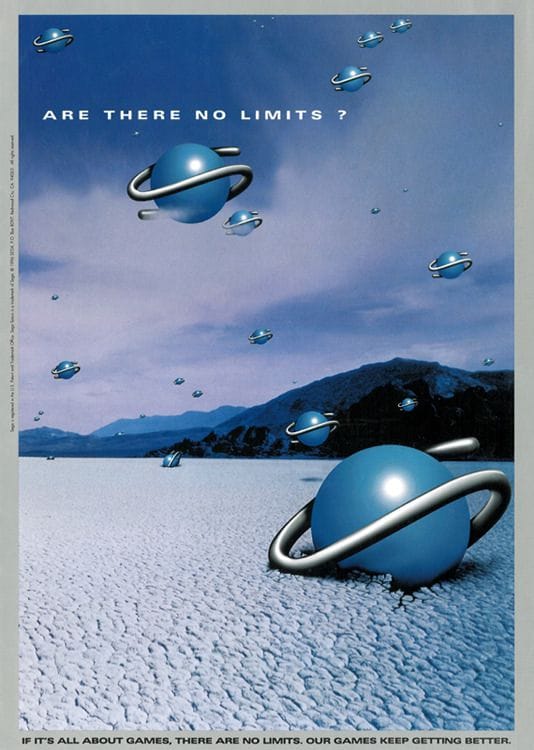

Sony’s branding didn’t hurt either. Their ads didn’t shout; they whispered in your ear. Edgy, irreverent, and soaked in late-’90s attitude, the PlayStation brand didn’t need mascots or nostalgia. It had confidence, club culture and cyberpunk flair. Meanwhile, Sega flailed—unsure if it was selling arcade thrills, tech bravado, or a Saturday morning cartoon lineup.

As the PlayStation gained traction, third-party studios began abandoning Sega almost en masse. EA, a juggernaut of the 16-bit era, took one look at Saturn’s convoluted architecture and Sega’s chaotic strategy—and walked away. Fan-favorite Working Designs, known for its lavish RPG localizations, followed suit after souring on the technical headaches.

This shift was particularly devastating in genres where Sega had once dominated. RPGs, platformers, and arcade-style action games—the lifeblood of 16-bit success—started migrating toward Sony’s system. Even loyal developers felt the pull: the financial and creative incentives of the PlayStation outweighed the challenges of Saturn development.

By 1996, the exodus was clear. High-profile titles that could have bolstered the Saturn’s library either landed on PlayStation first or bypassed Sega entirely. Without a strong third-party lineup, the Saturn struggled to sustain momentum. Hardware power alone wasn’t enough; the console war was as much about software as silicon, and on that front, Sega was losing ground fast.

The departure of developers didn’t just limit game variety—it eroded consumer confidence. Gamers noticed where the hits were coming from, and when PlayStation exclusives dazzled while Saturn ports lagged behind, the narrative of Sega’s mismanagement became undeniable.

Games That Couldn’t Save It

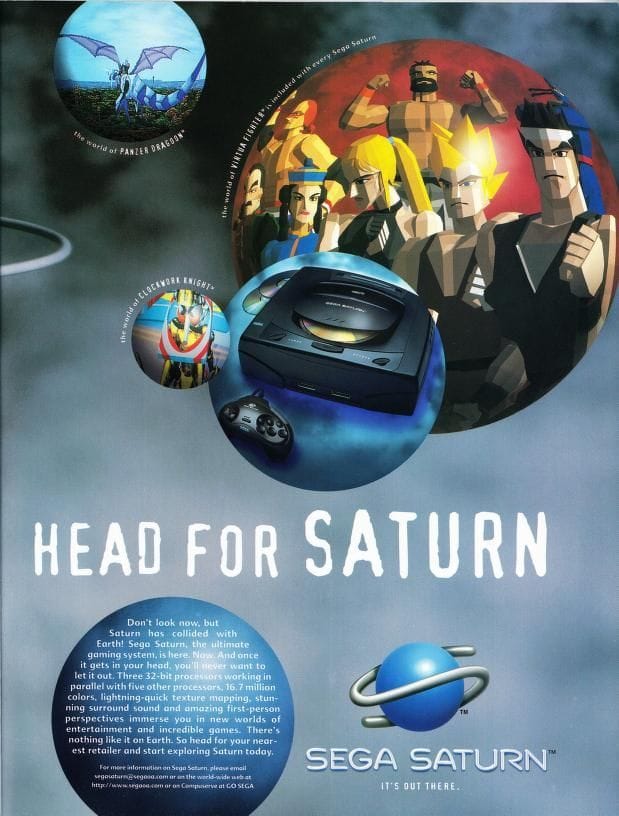

For all its horsepower and hype, the Saturn stumbled out of the gate with a launch lineup that felt more like a shrug than a statement. In North America especially, the early library lacked spark. Clockwork Knight, Bug!, and Daytona USA were decent distractions, but none of them screamed “next-gen.” Meanwhile, Sony hit the ground running with Ridge Racer, Battle Arena Toshinden, and a slicker brand identity. The Saturn’s offerings felt fragmented, like leftovers reheated from the Mega Drive era.

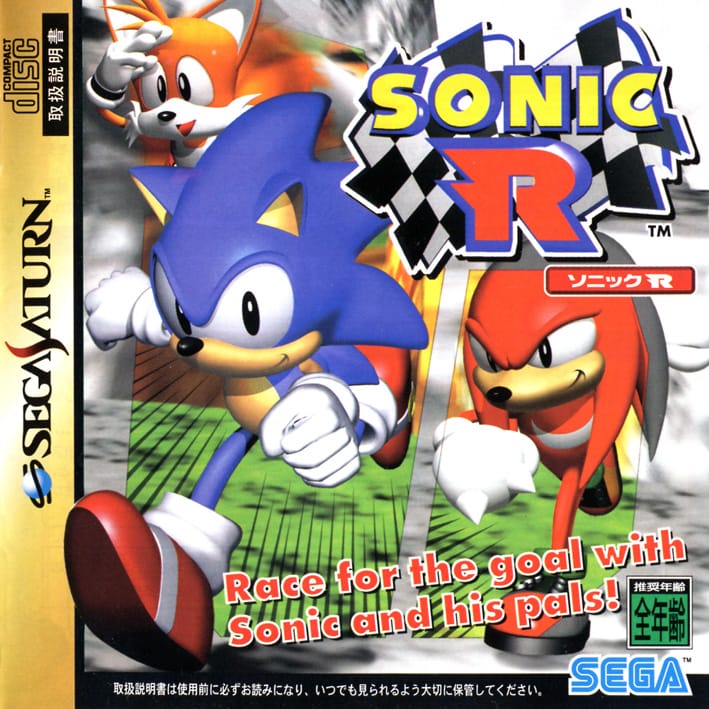

Then came the biggest sin: no Sonic. The blue blur, Sega’s golden goose, was nowhere to be seen at launch. Fans held out hope. Then waited. And waited. What they got was Sonic R, a colorful but shallow racing spin-off that felt more like a novelty than a system seller. Sonic X-treme, the game that was supposed to redefine the mascot in glorious 3D, became vaporware. Internal strife, technical limitations, and executive meddling buried it before it ever had a chance. Without Sonic, Saturn lacked its flagship—its cultural shorthand. It’s hard to overstate how damaging that was.

Despite the chaos surrounding its launch and architecture, the Saturn wasn’t entirely without triumphs. Its library included several arcade-perfect conversions that showcased the system’s true potential. Virtua Fighter, for example, brought the revolutionary 3D fighting experience from the arcades into living rooms with near-flawless fidelity. Its fluid animations, precise controls, and polygonal detail were a testament to what the Saturn could achieve when developers mastered its complexity.

Panzer Dragoon offered another highlight—a rail shooter drenched in style, atmosphere, and innovation. Its smooth 3D landscapes and surreal aesthetic stood out at a time when polygonal graphics were still a novelty. Likewise, Sega Rally captured the thrill of off-road racing with realistic handling and dynamic tracks, reinforcing the Saturn’s ability to translate arcade sensations to home consoles.

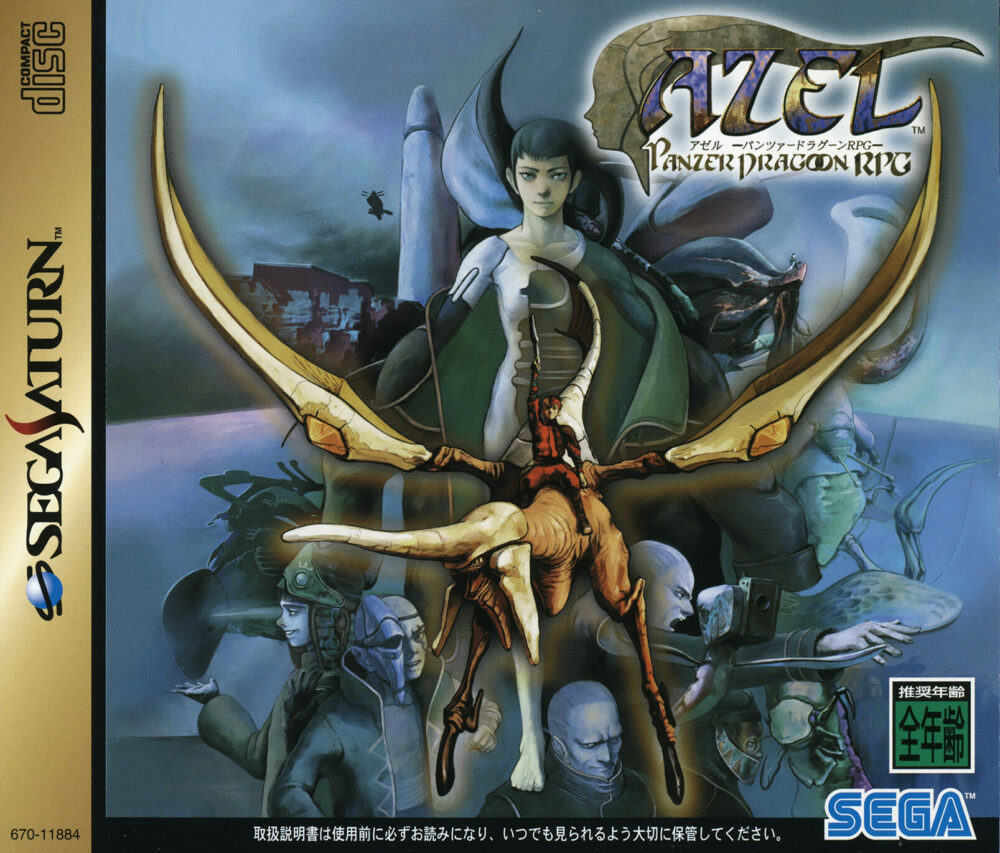

Back in Japan, the console told a different story. Games like Sakura Wars, Radiant Silvergun, Grandia, and Shining Force III made the Saturn a haven for RPG and shmup fans. But few of these masterpieces ever crossed the Pacific. Niche experimentation, once a strength in Japan, became a double-edged sword: it bolstered Saturn’s cultural cachet at home but left international gamers feeling disconnected from the system. Western audiences were left in the cold, watching from afar as Japanese players got all the good stuff. By 1998, Saturn’s library looked like a tomb of lost potential. Brilliant, but buried.

What Killed the Saturn?

The Sega Saturn wasn’t taken out by a single bullet. It was death by a thousand cuts—self-inflicted wounds, market misreads, and the unstoppable rise of a hungrier rival.

First, there was the hardware. Too complex, too soon. While the dual SH-2 CPUs and powerful video display processors gave the Saturn theoretical muscle, that power came wrapped in red tape. Developers spent more time wrestling with architecture than creating magic. In an era when time-to-market mattered, ease-of-development wasn’t a luxury—it was a lifeline. And Saturn cut its own.

Then came the culture clash. Sega of America and Sega of Japan rarely saw eye to eye, and when they did, it was often too late. The surprise North American launch, the schizophrenic marketing, the lack of unified vision—it all blurred the brand. Was Saturn the arcade-in-your-living-room console? The 2D purist’s dream? Or a next-gen 3D challenger? Even Sega couldn’t decide.

The 32X debacle only deepened the confusion. By cannibalizing resources and fragmenting the fanbase, Sega created a labyrinth of hardware with no clear direction. Consumers were left dazed. Retailers lost faith. Developers fled.

And looming above it all? Sony. The PlayStation’s $299 mic-drop, developer-friendly ecosystem, and lifestyle-driven marketing didn’t just outpace Saturn—it erased it from the conversation. Sega underestimated Sony’s appetite, charisma, and execution. The Saturn wasn’t a bad console. It was just misunderstood, mismanaged, and, ultimately, outmaneuvered.

Legacy of the Sega Saturn

The Sega Saturn may have stumbled out of the gate and limped through its commercial lifecycle, but in the decades since, it’s found something far more enduring than early success—cult immortality. In the hands of fans, tinkerers, and retro gaming obsessives, Saturn has been reborn.

Fan translations have cracked open the doors to its once-exclusive Japanese library. Games like Policenauts, Sakura Wars, and Shining Force III: Scenario 2 & 3—titles that never left Japanese shores—now speak fluent English thanks to tireless communities of hackers and linguists. For many, this is the Saturn’s real golden age: a renaissance of discovery, decades after the dust had supposedly settled.

On the technical side, Saturn emulation, once notoriously finicky due to the system’s labyrinthine hardware, has taken serious strides. Projects like Mednafen and Kronos have made once-impossible titles playable. Meanwhile, FPGA-based initiatives like the MiSTer have brought hardware-accurate Saturn performance to the modern era—something that once seemed like a pipe dream.

And for collectors? The Saturn is sacred ground. Rare PAL titles like Deep Fear or Panzer Dragoon Saga fetch eye-watering prices. Even common titles command attention thanks to their large-format jewel cases, anime-infused box art, and boutique charm. What was once a misfire in the marketplace is now a trophy in the cabinet. Time didn’t forget the Saturn—it just took time to understand it.

Conclusion

The Sega Saturn wasn’t a failure because it lacked power, vision, or ambition. It failed because it had too much of all three—and not enough cohesion to hold it all together. It was innovation without direction. Brilliance without a blueprint. A beast of a console caged by mismanagement.

At its core, Saturn’s downfall was a human story. Of departments pulling in opposite directions. Of Sega of Japan and Sega of America acting like rivals instead of allies. Of rushed decisions made in boardrooms rather than developer labs. The result was chaos masquerading as strategy.

And yet, from that wreckage came invaluable lessons. The Saturn’s defeat became the crucible in which the Dreamcast was forged—leaner, bolder, and finally, unified. It was Sega’s last stand in the hardware wars, but also its most focused. The company that had once been a house divided had finally found its voice… only to bow out while the crowd was still cheering.

The Saturn’s story is one of caution—but also cult legend. A machine too complex for its time, yet too special to forget. Its failure reshaped Sega’s destiny. Its legacy shaped a generation of gamers who, years later, still hear the boot-up chime echoing in memory.