In the late 1980s, video games were dominated by one name: Nintendo. The NES reigned supreme in living rooms from Tokyo to Toledo, its grip on the industry so absolute that few dared to challenge it. But one company wasn’t content to play second fiddle forever. Sega, the arcade giant that had spent years trying — and failing — to crack the home console market, was about to unleash a machine that would shatter expectations, redefine gaming, and kickstart a rivalry that would ignite the industry for years to come.

That machine was the Sega Genesis.

Armed with blistering 16-bit power, thunderous arcade-quality sound, and an attitude that sneered at the family-friendly image of its rival, the Genesis wasn’t just a new console — it was a declaration of war. From its audacious marketing to a library of unforgettable hits, Sega’s bold gamble proved that Nintendo wasn’t untouchable. This is the story of how the Genesis took on a giant, won over millions, and sparked a revolution that changed video games forever.

Sega’s First Steps into the Console Wars

Before Sonic’s lightning-fast spin dashed onto the world stage, Sega’s ambitions were already bubbling beneath the surface — and they were anything but modest. In 1983, the SG-1000 emerged as Sega’s inaugural home console. Released on the same day as Nintendo’s Famicom in Japan, it was destined to fight a losing battle right out of the gate. Timing, as it turns out, is everything.

With a limited selection of games and a marketing presence that barely made it past the horizon, the SG-1000 was a noble but underpowered attempt to pivot Sega’s arcade dominance into the living room. By the time the SG-1000 II arrived in 1984 with a few cosmetic tweaks, Nintendo’s head start had turned into a landslide. The Famicom’s sprawling library and the irresistible allure of Super Mario had already captured the hearts (and wallets) of Japanese gamers. Sega’s first shot had fizzled, not fired.

Undeterred, Sega went back to the drawing board. Enter the Mark III: a sleeker, technically superior machine brimming with 8-bit muscle. Its graphics outclassed the NES on paper, and its FM sound module (in Japan) promised lush audio Nintendo fans could only dream of. Yet in Japan, the Mark III’s moment came and went with little fanfare, overshadowed by Nintendo’s stranglehold on third-party developers who were forbidden from putting their games on rival platforms. Sega’s dreams of knocking Nintendo off its perch were left smoldering in the wake of restrictive contracts and missed market windows.

But this story doesn’t end in Japan’s arcades or cramped living rooms. Sega, ever the scrappy underdog, knew the world was bigger than one island nation. The Mark III was reimagined as the Sega Master System for Western audiences — a bold, confident name for a console determined to make waves where the NES hadn’t yet cemented itself as untouchable.

In 1986, the Master System arrived in North America with sharper visuals, a distinctive futuristic design, and a level of technical sophistication that put it head and shoulders above Nintendo’s aging 8-bit hardware. Yet in a cruel twist of fate, Sega’s timing once again betrayed them: the NES was already a household name, enjoying a monopoly-like grip on store shelves and retailer loyalties. Many stores refused to stock Sega’s console at all, leaving the Master System fighting for scraps.

Still, the Master System’s tale wasn’t one of total defeat. In Europe, where Nintendo’s distribution was patchy and delayed, Sega’s console became the de facto gaming system of choice. Kids in the UK, France, Spain, and beyond grew up with Alex Kidd’s oversized fist instead of Mario’s plumber jumps. In Brazil, the Master System became more than a console — it was a cultural phenomenon. Thanks to Sega’s partner Tec Toy, it sold in mind-boggling numbers, and new Master System hardware would continue to be manufactured in Brazil decades after Nintendo had long since moved on.

Sega’s early consoles didn’t dethrone Nintendo in Japan or North America. But in these key battlegrounds abroad, they laid the foundations for something far more explosive. Sega had learned hard lessons about timing, distribution, and the power of regional tastes. And with those lessons came a hunger to strike back — to shake up the status quo and unleash a machine so powerful, so unmistakably cool, that it couldn’t help but turn heads. The Genesis was coming. And this time, Sega was going to play for keeps.

Learning from Failure: Sega’s Motivation to Go 16-Bit

As the 8-bit wars raged on, Sega found itself watching from the sidelines in its home turf and the crucial North American market. The Master System’s technically superior specs weren’t enough to break Nintendo’s iron grip on third-party developers, which left Sega fighting an uphill battle with a smaller, often less compelling library of games. In Japan, the Mark III had become an afterthought almost as soon as it hit shelves, with Nintendo’s Famicom continuing its unstoppable march.

In North America, Nintendo’s policies all but froze Sega out of retail, while parents and kids alike gravitated toward Mario’s familiar face. For Sega, it wasn’t just a commercial failure — it was a wake-up call. They realized they couldn’t just match Nintendo; they had to leapfrog them entirely. And so the dream of bringing a true 16-bit arcade experience into homes was born. Sega leadership knew they needed a console so advanced and so desirable that it would render the NES obsolete overnight. Their goal was simple but audacious: blow Nintendo out of the water before the Big N even realized they were under attack.

Yet as grim as the Master System’s fortunes looked in Japan and America, glimmers of hope appeared in places Sega never expected. In Europe, Nintendo’s slow and patchy distribution left a massive opportunity. British and European retailers, unencumbered by Nintendo’s aggressive licensing deals, happily stocked the Master System, giving Sega a critical early foothold. In countries like the UK, France, and Spain, Alex Kidd became a bigger childhood hero than Mario, and Sega’s arcade ports made the Master System a hit among older kids who craved more action than the NES’s cutesy offerings.

Even more dramatic was the Master System’s meteoric rise in Brazil. Partnering with local electronics giant Tec Toy, Sega localized, manufactured, and distributed the console in a market largely untouched by Nintendo. The result was nothing short of a phenomenon: the Master System became Brazil’s national console, selling millions of units and even spawning exclusive games that wouldn’t exist anywhere else in the world.

These unexpected wins proved two critical things to Sega: first, they could succeed — even thrive — if they found the right markets and partners; second, the world was hungry for an alternative to Nintendo’s family-friendly image. Armed with these lessons, Sega prepared to swing for the fences with a new system — one built on cutting-edge technology and a brash, arcade-inspired attitude that would leave no doubt about who was bringing the future of gaming home.

Sega wasn’t just another console manufacturer — they were arcade royalty. By the mid-1980s, they’d built a reputation for spectacular cabinets that devoured quarters worldwide. At the heart of that arcade success was the System 16 board, a cutting-edge platform. This hardware was the engine behind hits like Altered Beast, Golden Axe, Shinobi, and E-SWAT — games bursting with detailed sprites, smooth scrolling, and an intensity home consoles simply couldn’t match.

When it came time to design a new system that could topple Nintendo, Sega didn’t need to start from scratch. Instead, they looked at their proven arcade technology and asked: why not put System 16’s power directly into living rooms? By adapting its architecture for a home console, Sega could deliver a genuine arcade experience without compromise — a promise no competitor could touch. It was a bold move that leveraged Sega’s greatest strength and laid the foundation for the Genesis’ blistering performance.

But translating arcade dominance into home success wasn’t as simple as swapping PCBs for cartridges. As Hideki Sato, Sega’s head of R&D, would later admit, “The problem was, while we knew how to make arcade games, we didn’t really know anything about console development.” Console gaming demanded long-play experiences, diverse genres, and a robust library to keep players engaged for weeks, not just minutes. Sega’s engineers had to learn to balance flashy arcade thrills with the depth expected by home audiences.

Money was tight, and time was even tighter. Rather than crafting an entirely new chipset, Sato and his team built the Mega Drive around what they already knew: System 16. It was a clever shortcut that let Sega punch above its weight technically, but it also forced them to master new disciplines, from memory management for longer games to creating ergonomic controllers players would use for hours on end. This crash course in console design would prove invaluable — and gave the Genesis an unmistakable arcade DNA that would set it apart from every other system on the market.

Designing the Beast: The Mega Drive’s Hardware Origins

At the heart of the Mega Drive beat a processor that was practically synonymous with arcade excellence: the Motorola 68000. Used in everything from high-end computers like the Amiga and Macintosh to Sega’s own System 16 boards, the 68000 was a 16-bit powerhouse that could juggle large sprites, handle complex animations, and manage smooth scrolling with ease. For players used to the NES’s flickering graphics and stuttering performance, the jump in visual fidelity was like night and day.

“The [Motorola] 68000 had all the qualities we were looking for. There were no other comparable chips on the market.”

- Masami Ishikawa, Sega

The 68000’s speed and sophistication meant that developers could bring Sega’s arcade hits to the living room without gutting them beyond recognition. Games like Altered Beast and Golden Axe looked and played like their coin-op counterparts — something no 8-bit system could dream of achieving. In an industry where “arcade perfect” was the holy grail, the 68000 made that promise real for the first time on a home console.

But Sega didn’t stop at one CPU. They cleverly added a Zilog Z80 — the same processor at the heart of the Master System — as a secondary chip. Its primary job was to handle sound processing, freeing the main 68000 CPU to focus on gameplay and graphics. This allowed for more complex audio without sacrificing performance, giving games a layered richness that felt light-years beyond the NES’s primitive bleeps.

Even better, the Z80 opened the door to backwards compatibility with the Master System library. With a simple adapter, players could plug in their old Master System cartridges and instantly access a massive library of 8-bit games. For families who’d invested in Sega’s previous console, this feature offered an enticing reason to upgrade, while also giving the Mega Drive a head start with hundreds of playable titles right from launch.

If there’s one element of the Genesis that still sends shivers down the spines of retro fans, it’s the system’s distinctively crunchy, driving FM music — and that sound all comes down to the Yamaha YM2612 chip. This six-channel FM synthesizer was a monster compared to the NES’s simple tone generator, capable of producing sweeping synth leads, growling bass lines, and digitized percussion that gave Genesis games their unmistakable audio identity.

From the pulsing beats of Sonic the Hedgehog’s Green Hill Zone to the atmospheric riffs of Streets of Rage, the YM2612 helped define an entire generation of gaming soundtracks. Paired with the Texas Instruments PSG (Programmable Sound Generator) inherited from the Master System, the Genesis could layer classic chiptune sounds with rich FM synthesis, creating some of the most dynamic and memorable music in 16-bit gaming history.

The Mega Drive wasn’t content to merely match the NES — it was engineered to leave it gasping for air. The Yamaha 7101 display processor inside Sega’s 16-bit beast could render up to 64 colors on screen simultaneously from a palette of 512, a mind-blowing leap over the NES’s max of 25 colors. This meant richer, more detailed worlds filled with gradients, shadows, and vibrant effects that made NES games look downright primitive by comparison.

Then there were the sprites: the Mega Drive could handle up to 80 on screen at once, compared to the NES’s struggle with even 8. This gave games a new level of dynamism, with massive bosses, swarms of enemies, and fluid animation that brought Sega’s arcade-style action roaring to life in ways no 8-bit console could dream of matching.

While Nintendo stuck with the basics, Sega poured innovation into every inch of the Mega Drive’s design. One of its coolest features was right on the front: a dedicated, amplified headphone jack. Plug in your headphones, and you’d hear the YM2612’s FM synth in glorious stereo — an experience so immersive it felt like a private arcade in your living room. This wasn’t just a gimmick; it was a signal that Sega was catering to older, more discerning players who demanded premium features.

Around back, the Mega Drive’s multi-AV port supported not just RF and composite video, but also analog RGB output — a feature virtually unheard of in home consoles of the era. On the right display, this meant razor-sharp visuals that rivaled professional arcade monitors, giving Sega’s games a crisp, vibrant look that made Nintendo’s NES graphics seem dull and muddy by comparison. Together, these features proved Sega wasn’t just building a console — they were crafting an experience that felt advanced, luxurious, and unapologetically cool.

Sega didn’t just want the Mega Drive to look like another toy under the TV — they wanted it to feel like a serious piece of tech. Drawing inspiration from high-end stereo systems, Sega’s designers gave the console a sleek, angular shell with glossy black plastic and a circular, turntable-like dome surrounding the cartridge slot. Bold “16-BIT” lettering, raised and originally printed in shimmering gold, crowned the system like a badge of honor, instantly signaling its next-generation power.

This design was deliberate: Sega aimed to attract older gamers and teens who were aging out of the NES’s kid-friendly aesthetic. By making the console resemble an expensive piece of audio equipment, Sega sent a clear message — the Mega Drive wasn’t a toy, it was a statement. It oozed style, attitude, and a sense of premium quality that set it apart from anything else on the market.

Just as important as the console’s striking looks was the feel of its controller — the gateway between players and the action. The Mega Drive’s 3-button gamepad was a radical departure from the small, boxy designs of the NES and Master System. Sega crafted a larger, more contoured shape that fit comfortably in adult hands, with rounded grips that made marathon gaming sessions easier on the thumbs and wrists.

The three action buttons (A, B, and C) gave developers more flexibility in gameplay design compared to the NES’s two-button layout, opening the door to more complex control schemes for fighting games, shooters, and sports titles. The controller’s responsive D-pad was borrowed from Sega’s arcade cabinets, giving it a level of precision and comfort rarely seen in home consoles of the era. Together, the Mega Drive’s look and feel established a bold new standard — one that said Sega wasn’t just playing catch-up with Nintendo, they were redefining what a home console could be.

Japan’s Launch: A Quiet Start

On October 29, 1988, the Mega Drive hit Japanese store shelves with an aggressive price point of 21,000 yen (about $150 at the time). Sega wanted to make a splash with a 16-bit powerhouse, and the launch lineup reflected their arcade pedigree: Space Harrier II, a bold, fast-paced sequel to one of Sega’s most famous arcade hits, and Super Thunder Blade, a thrilling helicopter shooter.

But Sega’s ambitions came with a catch — the Mega Drive didn’t include a pack-in game, forcing early adopters to shell out extra cash just to play. And while Space Harrier II’s smooth scaling effects were technically impressive, it wasn’t enough on its own to create an instant phenomenon. Without a killer app that could capture the mainstream, Sega’s new system landed with more of a whimper than a bang.

To make matters worse, the Mega Drive’s launch came just one week after Nintendo dropped a nuclear bomb on the Japanese gaming market: Super Mario Bros. 3. Mario’s grandest adventure yet was a critical and commercial juggernaut, quickly becoming a cultural event that sucked all the air out of the room. Even Sega’s flashy new hardware couldn’t compete with the must-have magic of Mario.

As a result, early sales of the Mega Drive in Japan lagged behind Sega’s expectations. Despite its superior technology, the console struggled to find momentum in a market still completely enthralled with Nintendo’s Famicom — especially when so many beloved third-party developers were locked into exclusivity deals with Nintendo. For Sega, it was a sobering reminder that great hardware alone wouldn’t win the war. They needed better games, smarter marketing, and a fresh approach if they were going to break Nintendo’s grip on the home console market.

Bringing the Revolution West: Enter Sega of America

As the Mega Drive was floundering in Japan, Sega knew that conquering North America — the world’s largest gaming market — was critical to their survival. In February 1989, they hired Al Nilsen as Director of Marketing for Sega of America. His first assignment? No big deal — just figure out what to call Sega’s make-or-break console in a region where “Mega Drive” was already trademarked.

Nilsen dove into market research and focus groups, juggling a shortlist of five potential names. The stakes were enormous: the right name could ignite curiosity and signal a bold new start, while the wrong one might doom the console to obscurity. Nilsen knew Sega needed something that didn’t just describe a product, but promised something revolutionary.

“Basically, my first day on the job was ‘Hi! Tell us what name we should go with.’”

- Al Nilsen, Sega of America

Among the list of candidates, one name stood out like a bolt of lightning: Genesis. It was powerful, evocative, and spoke directly to the sense of transformation Sega wanted to project. This wasn’t just another console — it was a new beginning for gaming itself, a system that would shatter old expectations and usher in a bold, 16-bit future.

The name gave the console a unique identity in the U.S., separate from its Japanese and European siblings, and emphasized the console’s promise of a fresh start for both Sega and gamers tired of Nintendo’s 8-bit status quo. The Mega Drive and Genesis were virtually identical inside, but their different names reflected Sega’s determination to adapt to regional markets — a savvy move that paid off in a big way.

Genesis also perfectly matched Sega’s more aggressive, rebellious marketing strategy. Where Nintendo represented the status quo — safe, family-friendly, and familiar — Sega’s Genesis promised something edgier, faster, and more mature. The name helped instantly position Sega as the brand for players who were ready to move beyond childhood adventures and embrace a more intense, arcade-inspired experience. With the name decided, Sega of America was ready to go to war.

Sega of America’s team made a few key changes to help the Genesis stand out on U.S. shelves. The iconic raised “16-BIT” lettering on the Mega Drive, originally bold and shimmering gold, was reduced in size and switched to a sleek silver, giving the console a more refined, modern look.

Al Nilsen and his team also added the bold “Genesis” logo under the cartridge slot, plus the phrase “High-Definition Graphics” curving proudly around the console’s dome — a cheeky nod that made the Genesis sound like cutting-edge tech straight out of an electronics showroom. These tweaks didn’t just look cool; they helped hammer home Sega’s message that the Genesis wasn’t another kiddie console. It was high-performance hardware for players who wanted a serious, arcade-quality experience at home.

On August 14, 1989, the Sega Genesis stormed onto American shelves, determined to shake Nintendo’s seemingly unbreakable grip on the market. This time, Sega knew it needed more than flashy hardware specs — it needed a game that showed off the console’s raw power right out of the box. Enter Altered Beast: a thunderous, arcade-perfect brawler where players transformed into mythical creatures and unleashed pixel-crushing attacks.

Altered Beast came bundled as the pack-in title, instantly demonstrating what 16-bit could mean in your living room. Alongside it, five additional launch titles were ready for early adopters: Last Battle, Space Harrier II, Super Thunder Blade, Tommy Lasorda Baseball, and Thunder Force II. Each showed a different facet of what the Genesis could do, from frenetic shooters to deep sports sims, signaling to gamers that this wasn’t just another NES clone — it was something entirely new.

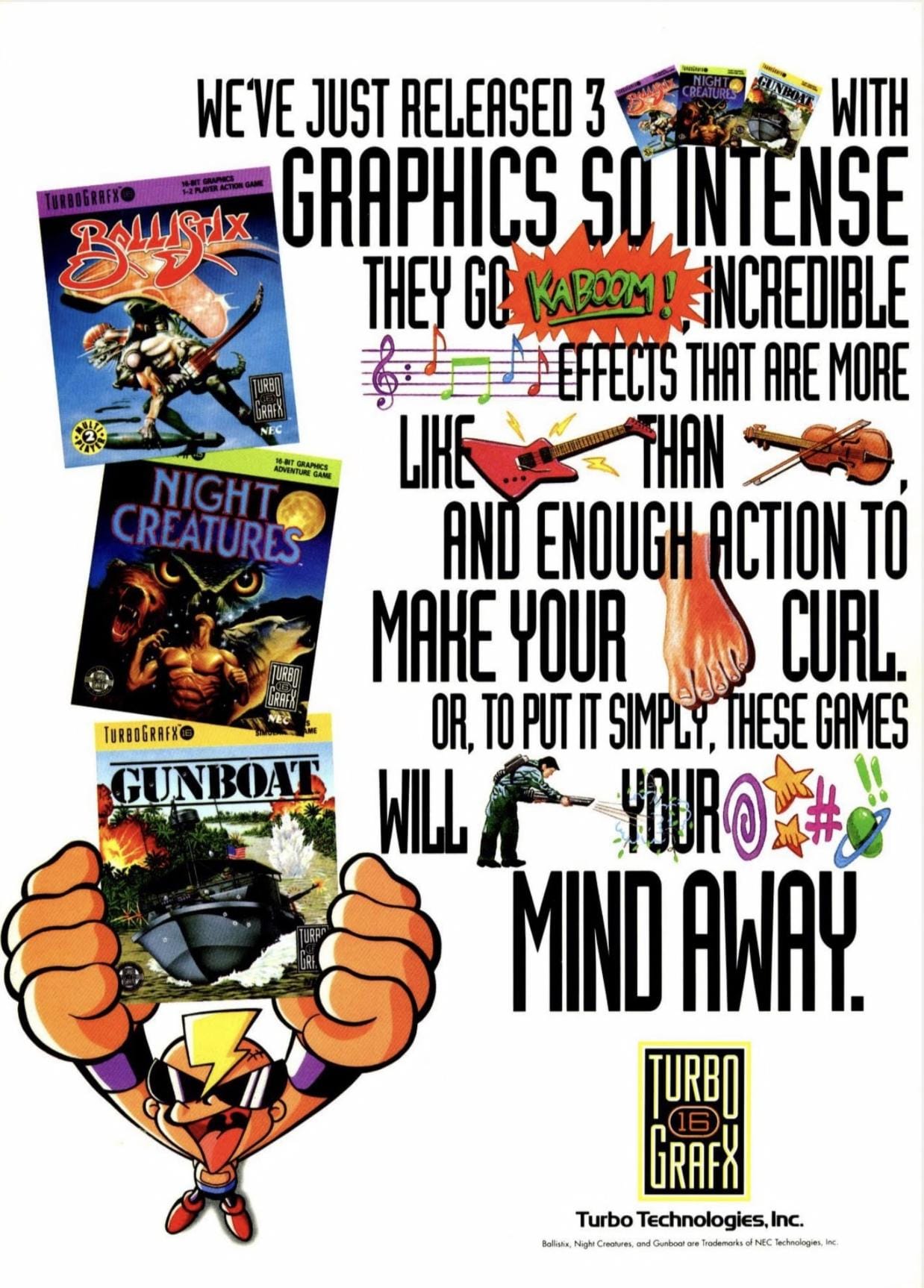

The First 16-Bit Face-Off: Genesis vs TurboGrafx-16

Sega wasn’t the only company eyeing Nintendo’s throne. NEC, a giant in Japan’s electronics industry, partnered with Hudson Soft to launch the PC Engine — a sleek little console that was a surprise hit in Japan. When it came time to bring it stateside, NEC gave it a bigger shell and a new name: the TurboGrafx-16. Launched in North America just a week after the Genesis, the TurboGrafx-16 was marketed as a 16-bit competitor, despite technically using an 8-bit CPU with a 16-bit graphics chip.

To casual gamers, NEC’s clever branding made the TurboGrafx-16 sound just as advanced as Sega’s true 16-bit powerhouse. NEC hoped to win over players with bright, colorful visuals, slick marketing, and a price point that matched the Genesis — but the fight for the next generation of gaming had only just begun.

The TurboGrafx-16 and Genesis both needed to prove themselves with early killer apps — and for many players, that meant shooters. NEC came out swinging with Blazing Lazers, a fast, polished vertical shooter that showcased the Turbo’s impressive sprite work and smooth scrolling. Blazing Lazers dazzled players with big bosses, vibrant stages, and intense action, making it one of the Turbo’s standout early titles.

Sega countered with Thunder Force II, a game that brought frenetic, multi-directional shooting and an iconic soundtrack to the Genesis. Its mix of overhead and side-scrolling levels gave it a unique flavor, and its technical performance was a clear flex of the Genesis’ 16-bit muscle. These games weren’t just entertainment — they were weapons in the first true 16-bit console war. While neither system delivered an instant knockout blow, the Genesis’ arcade pedigree and Sega’s aggressive marketing would soon give it the edge, even as the TurboGrafx-16 quietly slipped into the background.

The Games That Defined The 90s

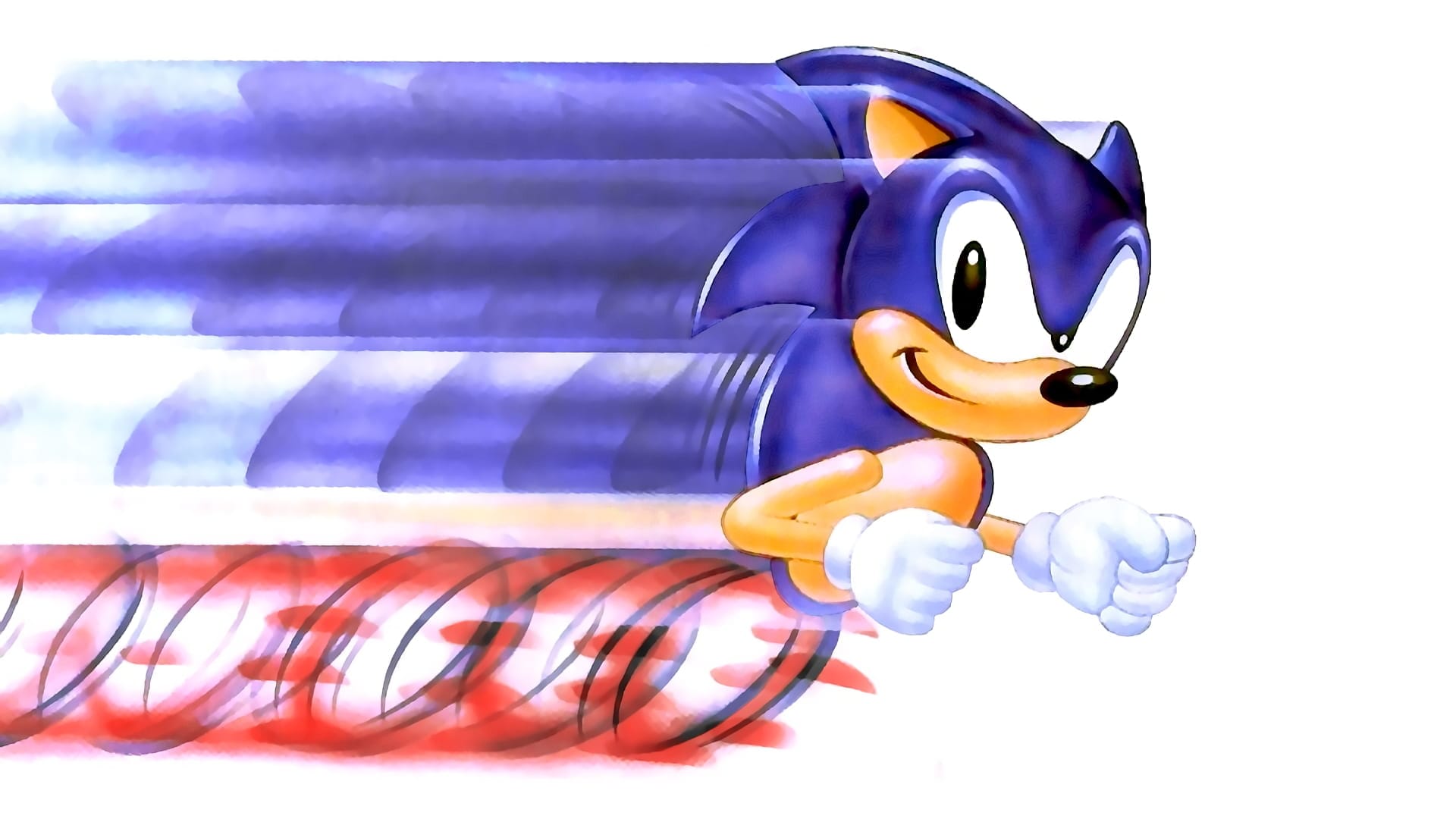

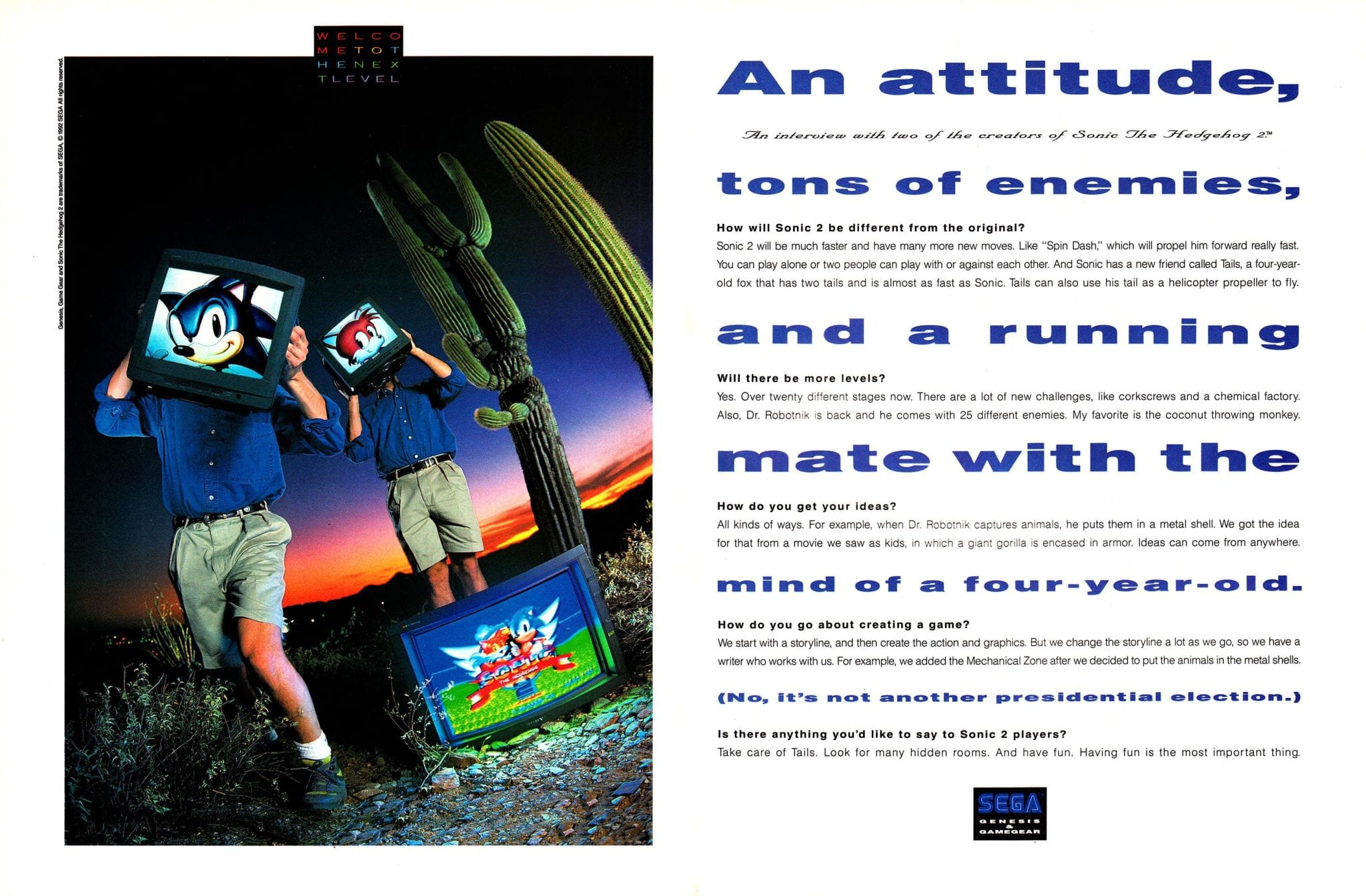

Every console has its heroes, but the Sega Genesis roster was something else entirely—a pantheon of icons that pulsed with energy, attitude, and a fierce sense of style. When Sonic the Hedgehog hit store shelves in June 1991, it was nothing short of a phenomenon. Kids begged their parents for the Genesis, not because it was 16-bit, but because it had Sonic.

The blue blur became the symbol of cool gaming. Sales soared. Sega’s market share jumped from a distant afterthought to a fierce competitor, clawing up to nearly half the U.S. market within a year. And then came Sonic the Hedgehog 2—bigger, faster, smoother. It turned speed into spectacle, multiplayer into chaos, and cemented Sonic as a pop culture icon.

Streets of Rage brought the gritty allure of late-night arcades to living rooms everywhere. Axel, Blaze, and Adam weren’t superheroes—they were street-level saviors, pounding justice into a decaying cityscape. The music by Yuzo Koshiro? Legendary. The gameplay? Addictive. Streets of Rage 2 refined the formula into perfection, with slick animations, brutal combos, and the kind of couch co-op that forged lifelong friendships. Few games felt so effortlessly cool.

Comix Zone didn’t just look like a comic book, it was one. It was a hand-drawn masterpiece, with every punch, every jump, every frame crackled with imagination. The sound design amplified that raw, underground energy, and the kind of distorted edge that screamed Sega’s 16-bit FM synth at full blast. It was stylish, surreal, and unapologetically experimental, pushing the Genesis to its artistic limits.

If there was ever a game that embodied the phrase “go big or go home,” Contra: Hard Corps was it. Building on Konami’s arcade heritage, this Genesis exclusive cranked the intensity to eleven—branching paths, towering bosses, and a soundtrack that practically melted speakers. It was brutally difficult, yes, but in that glorious, satisfying way that made victory feel earned. Hard Corps was the Genesis flexing its muscles, proving it could deliver action faster, louder, and tougher than anyone else.

Then came Earthworm Jim—the absurd masterpiece that only the ‘90s could have produced. A snarky worm in a super suit, slinging cows and quipping like a Saturday morning antihero. The humor was bizarre, the animation groundbreaking, the gameplay razor-sharp. It embodied Sega’s anarchic energy: weird, witty, and impossible to ignore. Jim wasn’t a mascot; he was a movement—proof that the Genesis was the home of the unconventional.

While Sonic raced through loops and Streets of Rage ruled the back alleys, the Sega Genesis had far more up its sleeve. Gunstar Heroes was fast, flashy, and impossibly smooth. Shining Force took the slow, cerebral world of strategy RPGs and made it accessible and addictive. Beautiful, strange, and quietly haunting, Ecco the Dolphin was unlike anything else on the Genesis. No other game radiated as much personality as ToeJam & Earl. These titles didn’t just pad the Genesis library—they defined its identity. They proved Sega’s console could do more than just speed and attitude. It could tell stories, build worlds, and capture imaginations in ways no one expected

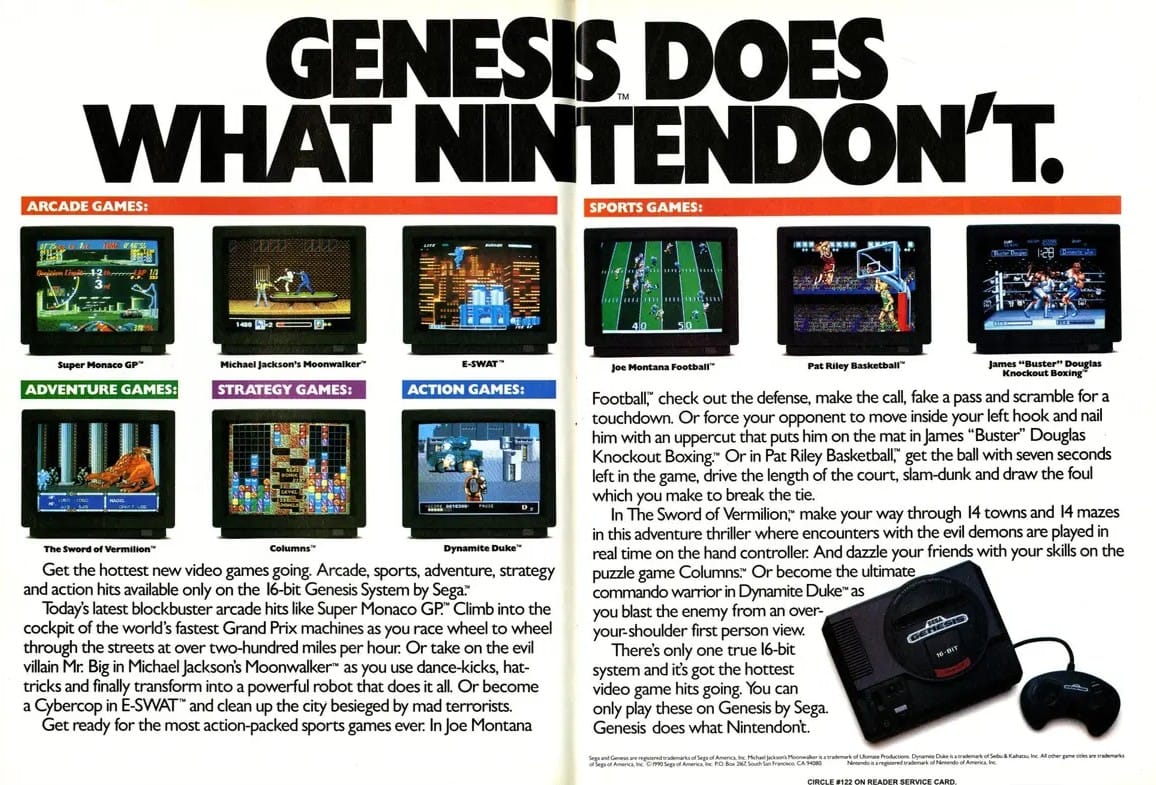

Genesis Does What Nintendon’t

Nintendo ruled the late ’80s with an iron fist, controlling about 95% of the American home console market at its peak. Sega knew that if it played by the same rules, it would lose. So instead, it threw the rulebook out the window. In 1990, Sega launched the now-legendary “Genesis Does What Nintendon’t” campaign — a bold, in-your-face series of TV spots and print ads that openly mocked Nintendo’s aging NES.

These ads were brash, stylish, and unforgettable, hammering home the Genesis’ strengths: faster gameplay, more colors, bigger sprites, and an unbeatable arcade feel. They highlighted exclusive titles like Altered Beast and the upcoming Sonic the Hedgehog, all while portraying the NES as yesterday’s news. The slogan became an instant classic — a rallying cry that made Sega look like the rebellious underdog everyone wanted to root for.

Sega’s secret weapon wasn’t just better hardware; it was attitude. Unlike Nintendo’s wholesome, kid-friendly image, Sega doubled down on a tone that was faster, cooler, and undeniably edgier. Their ads dripped with sarcasm and swagger, speaking directly to teenagers and college students who were ready to move beyond cute plumbers and Saturday morning cartoons.

Sega’s marketing blitz featured loud rock soundtracks, high-octane visuals, and messaging that made owning a Genesis feel like joining an exclusive club of thrill-seekers. This new identity resonated deeply with players who wanted something more intense than Nintendo’s safe, family-oriented fare. Sega didn’t just sell a console — it sold a lifestyle. And in doing so, it successfully carved out a massive, loyal fanbase that would soon transform the Genesis into a pop-culture phenomenon.

The Sega CD and 32X Gamble

Looking to widen its lead even further in the 16-bit wars, Sega of Japan engineered the Mega-CD—rebranded as the Sega CD in the States. It wasn’t even born as a gaming machine. The original plan was simply to create a cheap audio drive, but Sega pivoted, realizing that optical discs could store far more data than cartridges ever could. That extra space, they believed, was the key to bigger, better games.

When the Sega CD hit American shelves in the fall of 1992, the mood was optimistic. The add-on carried a hefty $299 price tag—twice the originally projected $150—but early adopters still bit. The hardware snapped onto the Genesis like some cybernetic upgrade and promised a future of high-capacity gaming. And in some ways, it delivered. Players got access to titles like Sonic CD, Virtua Fighter, Virtua Racing, and of course, the infamous FMV game Night Trap. For a while, it felt like Sega had struck gold, proving that consumers really would shell out for an add-on if it offered something new.

But the honeymoon didn’t last. Beneath the promise of shiny discs lurked some very real flaws. Graphics were often grainy, load times stretched patience, and that steep price stung especially hard as whispers of “next-gen” consoles grew louder. Worst of all, the library was padded with retooled Genesis games—Mortal Kombat, Eternal Champions, Streets of Rage—that hardly justified the cost of admission.

The Sega CD burned bright, but like its overworked motors, it overheated quickly. What started as Sega’s great leap into the CD age ended up a cautionary tale: a moderate success, but ultimately a stopgap on the road to the company’s more notorious hardware missteps.

Genesis add-ons were already confusing consumers, but Sega somehow decided to double down. In a move that would baffle historians and fans alike, Sega of America went all-in on an add-on. Enter the 32X—a mushroom-shaped peripheral for the aging Genesis that promised 32-bit power at a bargain price. Released in November 1994, a little less than a month after the release of the Sega Saturn in Japan and a little less than a year from the Saturn’s American launch, the 32X was destined for failure.

On paper, it was Sega’s quick-and-dirty response to Nintendo’s FX chip and Sony’s rising threat. But in reality? It was a distraction. A detour. A desperate Hail Mary. For consumers, the message was murky at best. Sega had the Genesis. Then the Sega CD. Now the 32X. And another console—the Saturn—was just around the corner. Why invest in an expensive add-on with such a short shelf life? Why not just wait for the “real” next-gen machine? Retailers were confused. Gamers were skeptical. And the press… well, they had a field day.

Meanwhile, developers were stretched to their limits. Some were still making Genesis games. Others were tinkering with the Sega CD. Now they were being asked to support 32X and Saturn? Resources were splintered. Creativity was diluted. By trying to maintain three hardware ecosystems at once, Sega created internal chaos and external apathy.

As a result of the timing, the lack of quality games, and an awkward rollout, the 32X died on the vine. The 32X wasn’t just a mistake—it was a monument to overreach.

Legacy of a Legend

For all its early stumbles in Japan, the Genesis’ fortunes dramatically reversed overseas. In North America, Sega’s relentless marketing, growing library of arcade-quality hits, and the arrival of Sonic the Hedgehog helped the Genesis catch fire. By the early ’90s, Sega had wrestled away significant market share from Nintendo, even outselling the Super Nintendo in the U.S. at the height of the 16-bit wars.

Meanwhile, in Europe, the Mega Drive (as it retained its original name there) became the go-to system thanks to Nintendo’s slower distribution and weaker brand recognition. Games like FIFA Soccer turned Sega’s 16-bit console into a fixture in living rooms across the UK, France, Germany, and beyond. Sega’s cool image and arcade roots perfectly matched Europe’s love for fast, action-packed games, cementing the Mega Drive’s status as the must-have console of the era.

Then there was Brazil — a market that would go on to become one of the Genesis’ biggest success stories. Through a partnership with Tec Toy, Sega localized, produced, and sold the Mega Drive in Brazil with incredible results. Tec Toy not only made the console affordable and widely available, but also localized games, developed exclusive titles, and even kept manufacturing new versions of the Genesis long after Sega had left the hardware business elsewhere. By the time production finally wound down, Sega’s 16-bit machine had helped sell a staggering 30 million units worldwide, thanks in no small part to Brazil’s enduring love for the console.

The Sega Genesis wasn’t just another entry in the console wars — it was the system that proved Nintendo could be challenged and even beaten. It brought arcade-quality graphics, sound, and speed into living rooms at a time when 8-bit hardware was still the norm, setting a new standard for what home gaming could look and feel like. Its library of iconic titles — from Sonic the Hedgehog and Streets of Rage to Gunstar Heroes and Phantasy Star IV — continues to influence game design and inspire nostalgic re-releases to this day.

Thanks to its bold hardware choices, stylish design, and unforgettable soundtrack, the Genesis became more than a gaming console; it was a cultural touchstone for an entire generation of players. Even decades later, its distinctive look, unique sound, and legendary games make it one of the most beloved and recognizable consoles of all time.

Final Thoughts

More than three decades after it first thundered onto the scene, the Sega Genesis is still held up as a shining example of gaming done right. Its iconic library, trailblazing hardware, and unmistakable attitude continue to inspire retro collections, modern re-releases, and dedicated fan communities around the world. Whether it’s the crunchy beats of a YM2612 soundtrack or the thrill of blasting through Green Hill Zone, the Genesis evokes an era when games felt daring, fresh, and larger-than-life.

Collectors and casual fans alike celebrate the Genesis not just for nostalgia, but because its best titles remain endlessly playable, offering fast, responsive gameplay and timeless fun. It’s a testament to how great design and bold thinking can leave an impact that lasts for generations.

The Genesis didn’t just introduce Sonic or dazzle players with arcade-perfect hits; it proved that Nintendo’s dominance wasn’t unshakable. By building a powerful system, marketing it with fearless swagger, and capturing the hearts of teenagers everywhere, Sega forced the industry to evolve.

For a few glorious years, Sega wasn’t just competing — it was leading. The Genesis stands as a monument to Sega’s determination, innovation, and refusal to play it safe. Even decades later, its distinctive look, unique sound, and legendary games make it one of the most beloved and recognizable consoles of all time. It’s the console that changed the rules of the game, and for that, it will always be remembered as the 16-bit powerhouse that started a revolution.