The PlayStation 3 should have been a disaster. Launched into the gaming arena with a jaw-dropping $599 price tag, an infamously convoluted architecture, and a marketing campaign that ranged from overconfident to outright bizarre, Sony’s third console seemed destined for an early knockout. It was outpaced by the more affordable Xbox 360, outsold by the family-friendly Wii, and lambasted by developers who struggled with its enigmatic Cell processor.

Industry analysts wrote it off. Fans doubted its future. The gaming world watched as Sony, once the undisputed king of consoles, found itself stumbling out of the gate. And yet, against all odds, the PlayStation 3 clawed its way back.

What began as a cautionary tale of corporate hubris evolved into one of gaming’s greatest redemption arcs. A redesigned console, a library of generation-defining exclusives, and a commitment to long-term innovation turned the tide. This is the story of how Sony’s boldest gamble became one of the industry’s most unforgettable legends.

The Birth of the Cell

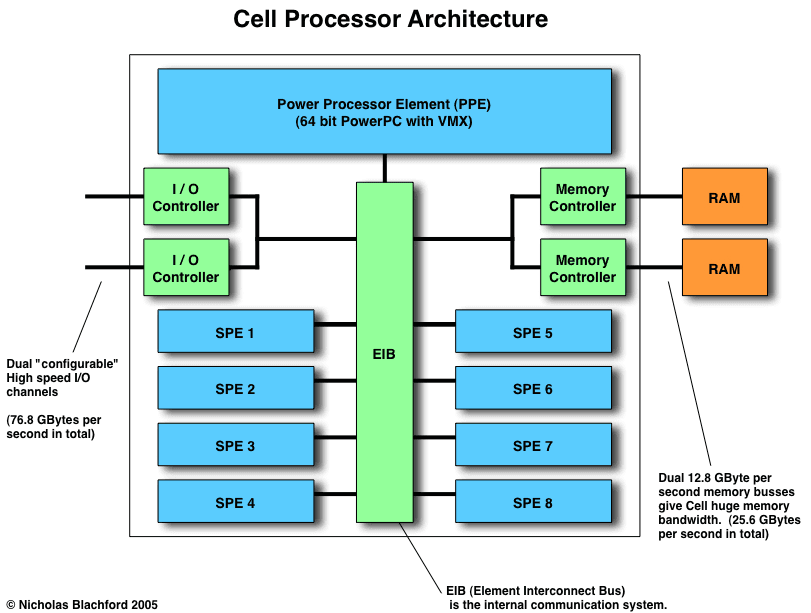

In March 2001, just a year after the PlayStation 2 took the world by storm, Sony was already looking ahead. Ken Kutaragi—the visionary behind PlayStation—believed the next console couldn’t just be powerful; it had to redefine computing itself. To achieve this, Sony struck a landmark partnership with Toshiba and IBM, creating the STI Alliance. The group set up shop in Austin, Texas, and over four long years, they designed a processor that was less like a game console chip and more like the beating heart of a supercomputer.

He imagined this beast of a CPU as a “supercomputer on a chip”, and that it could work similarly to biological cells in the human body. The Cell processor boasted a unique multi-core architecture capable of handling complex computations at lightning speed. On paper, it sounded revolutionary. In practice, it became a developer’s nightmare.

The “Cell Broadband Engine” was never meant for games alone. IBM eyed scientific and medical applications, Toshiba dreamed of high-performance TVs, and Sony wanted it all for their PlayStation 3. By the time the project neared completion in 2005, Sony’s commitment was undeniable—Kutaragi had poured an eye-watering $400 million into its development.

The result was a technological marvel, but also a ticking time bomb. The Cell was astonishingly fast, breathtakingly complex, and unlike anything developers had ever seen before. It was a chip built for the future—but one that would make the PS3’s present far more painful than Sony ever imagined.

E3 2005 – Sony Shows Its Hand

By the summer of 2005, Sony was ready to reveal its next masterpiece. At E3 in Los Angeles, the company held court with a press conference that stretched nearly two hours—an event less like a product launch and more like a grand performance. Every detail of the PlayStation 3 was laid bare: the hardware, the partnerships, the vision for what gaming could be.

When Sony unveiled the Cell Broadband Engine, it wasn’t just a processor—it was a statement. This cutting-edge chip promised to redefine gaming performance. Theoretically, this meant smoother physics, richer AI, and unparalleled graphical fidelity. Sony envisioned a machine that wouldn’t just rival high-end gaming PCs—it would eclipse them.

Front and center was the RSX “Reality Synthesizer,” a graphics processor co-developed with Nvidia. Sony promised visuals so lifelike they’d blur the line between cinema and gameplay. Tech demos and trailers filled the stage—Gran Turismo and Final Fantasy XIII—each carefully orchestrated to showcase a future where PlayStation 3 would be the undisputed king of graphics.

Then there was Blu-ray, Sony’s not-so-secret weapon in the format wars. By making it the standard for PS3 games, Sony banked on the idea that high-capacity discs would become the future of media. Beyond hardware, Sony was also laying the groundwork for the digital future. The PlayStation Network (PSN) arrived as Sony’s answer to Xbox Live, a fully integrated online service that allowed players to download games, connect with friends, and experience multiplayer battles.

But what stole almost as much attention was the controller. The bulbous, silver “Boomerang” design looked more like a prototype from a sci-fi prop department than a DualShock successor. Bold, yes—but fans and press alike weren’t convinced it was practical.

Still, Ken Kutaragi exuded absolute confidence. When asked about Microsoft’s upcoming Xbox 360, he dismissed the competition with a smirk:

“Beating us for a short moment is like accidentally winning a point from a Shihan (Karate master), and Microsoft is still not a black belt.”

It was classic Kutaragi—cocky, uncompromising, and completely certain that the PlayStation 3 would dominate the next generation. Sony wasn’t just designing a machine for the present—it was crafting a vision for gaming’s future. The PS3 was a console built on ambition.

The Cell Explained – Genius or Madness?

On paper, the Cell Broadband Engine was nothing short of revolutionary. Built around a 3.2 GHz Power Processor Element (PPE) and eight Synergistic Processing Elements (SPEs), it wasn’t just a CPU—it was a small army of processors working in tandem. The PPE acted like a general, issuing commands, while the SPEs were its foot soldiers, chewing through specialized tasks in parallel. According to AMD CEO Lisa Su, who was previously the Director of Emerging Products at IBM in 2001, she explained:

“We [IBM] started with a clean sheet of paper and sat down and tried to imagine what sort of processor we’d need five years from now.”

The architecture was asymmetric by design, a bold departure from the straightforward multicore chips developers were used to. Sony wasn’t handing out a simple machine; they were demanding the industry learn an entirely new way of programming. A game engine had to juggle tasks across six SPEs (two were reserved for OS and yield issues), while the PPE managed the chaos. It was powerful, yes—but also unforgiving.

For scientific computing, it was a dream. For video game developers, it was a headache of biblical proportions. Meanwhile, Microsoft’s Xbox 360 offered three standard PowerPC cores. Developers could scale their existing engines, port code more easily, and get results without tearing their hair out. Sony had built a console that looked like a supercomputer, but instead of empowering developers, it often left them drowning in complexity. The Cell was brilliant, misunderstood, and in many ways, its own worst enemy.

E3 2006 – From Pride to Punchline

A year after its dazzling reveal, Sony returned to E3 in 2006—but this time, the shine was gone. The PlayStation 3 on stage wasn’t the futuristic machine promised twelve months earlier. The hardware had been quietly scaled back: fewer USB ports, only one HDMI output, and the card readers that once made the PS3 look like a digital hub were nowhere to be seen.

The controller had also changed. Gone was the bizarre “Boomerang” design that had been mocked online, replaced with the safer, DualShock-like Sixaxis. It brought motion controls, but there was one glaring omission—rumble. Thanks to a messy legal battle with haptic technology company Immersion, Sony claimed vibration was “last-gen.” Players weren’t buying it.

And then came the moment that would haunt Sony for years. SCEA president Kaz Hirai stepped on stage to announce the launch details. When the words “$599” left his mouth, the room went silent. What was meant to be Sony’s victory lap instantly became a disaster. The internet pounced:

Thanks but no thanks, Sony.

I seriously thought about getting one of these at launch. Now I laugh at the idea.

I would rather just get a Wii or 360 instead.

The show only got worse. The awkward “Giant Enemy Crab” demo of Genji: Days of the Blade—complete with a promise of “realistic battles based on famous battles in Japanese history”—was promptly followed by a giant crustacean boss. A presenter triumphantly shouted, “Attack its weak point for massive damage!”—and gamers never let Sony forget it. Ridge Racer, once a system seller, became a punchline thanks to Hirai’s over-enthusiastic cry of “RIIIIIDGE RACER!” The phrase still echoes in internet forums today.

In one of the most shocking moments of E3 2006, Square Enix took the stage—not to announce another PlayStation-exclusive Final Fantasy, but to confirm that Final Fantasy XIII would also launch on Xbox 360. It was a gut punch to Sony loyalists. With Microsoft securing exclusive DLC deals and timed content, it seemed like the PlayStation’s golden age of third-party dominance was over.

That price tag wasn’t just high—it was astronomical for the time. Microsoft’s Xbox 360 had already hit store shelves a year prior with a lower entry price of $299 for the Core model and $399 for the Premium. Meanwhile, Nintendo’s Wii, launching later that year, carried an invitingly accessible $249 price point, complete with a fresh new approach to motion gaming.

“The room went silent. I said, ‘Did he really say what I think he said?’. Many of us said out loud, ‘Okay, this could be really fun. We got a real chance here. If we push hard, we can really make a difference.’” - Robbie Bach, Former Chief Xbox Officer

By the end of the show, Sony had turned what should have been its crowning moment into a comedy of errors. Microsoft smelled blood. With the Xbox 360 already on shelves at a cheaper price, Sony had handed its rival a golden opportunity. Suddenly, the PS3 wasn’t just the most expensive option—it was the hardest sell. For the first time in a decade, the PlayStation brand looked vulnerable.

The Infamous Launch

November 17, 2006. Instead of a triumphant celebration, the PS3 launch felt more like a survival test. Stores across North America received shockingly small shipments—some retailers had fewer than a dozen units to sell, while others got none at all. Lines formed days in advance, with hopeful fans camping outside in the freezing cold for their chance to snag Sony’s elusive machine.

The desperation spilled into chaos. Reports surfaced of armed robberies in parking lots, muggings in line, and even a shooting in Connecticut tied to a PS3 restock. Local news stations gleefully covered the hysteria, making the console look less like the future of entertainment and more like the cause of a small crime wave.

Scalpers, meanwhile, had a field day. Within hours of launch, PS3s flooded eBay at outrageous prices—$1,500, $2,000, even higher. Some buyers paid without hesitation, terrified that missing launch week meant missing the future. For many ordinary fans, though, the message was clear: unless you were lucky or rich, you weren’t getting a PlayStation 3 anytime soon.

Those lucky enough to bring one home weren’t entirely thrilled either. The console’s library at launch didn’t help matters either. Online connectivity was barebones, the PlayStation Store looked like a cheap web browser, and the slick XMB interface lacked many expected features. The launch lineup did little to justify the sky-high cost. While MotorStorm had its merits, the lack of true system-sellers left the PS3 looking weak next to the Xbox 360’s already robust lineup.

Meanwhile, the Wii was shattering records, pulling in casual and hardcore gamers alike with its novel motion controls and the cultural phenomenon that was Wii Sports. For a machine that cost more than most televisions at the time, the PS3 felt unfinished.

The early days were rough. Retailers struggled to move units. Sony’s once-loyal fanbase scoffed at the high cost and the company’s now-legendary “Get a second job” comment, a tone-deaf attempt to justify the price. The PlayStation 3 was losing ground. Sales lagged behind its competitors. The buzz was negative. The industry was watching to see if Sony could recover, or if the once-invincible PlayStation empire had finally overplayed its hand.

And yet, Sony was unshaken. Executives doubled down, promising a “10-year life cycle” for the PS3. The message was clear: this was not just a console—it was the future of entertainment. But in those first few months, that future felt very far away.

Multiplatform Games Struggle

If the chaotic launch wasn’t bad enough, 2007 cemented the PS3’s reputation as the underdog of the console war. While Sony banked on brand loyalty and the raw power of the Cell processor, the reality of development painted a different picture.

Across the industry, third-party games routinely performed better on Xbox 360. Blockbuster games ran smoother, loaded faster, and often looked sharper on Microsoft’s hardware. The PS3’s architecture wasn’t just different—it was hostile. Porting code from 360 to PS3 was like trying to fit a square peg into a triangular hole, and publishers weren’t eager to waste time and money making it work.

If the Cell processor was the PS3’s most intimidating feature, its memory setup was the console’s most limiting. Sony chose to split the system’s 512 MB of RAM right down the middle—256 MB of XDR main RAM for the CPU, and 256 MB of GDDR3 for the GPU. On paper, it sounded like a tidy division. In practice, it tied developers’ hands.

The Xbox 360, by contrast, offered a unified 512 MB pool of RAM that could be allocated however teams saw fit. If a game needed more memory for visuals, no problem—just funnel more into the GPU. If physics or AI demanded extra cycles, the CPU could claim the lion’s share. That flexibility made Xbox development much smoother, especially for studios building multiplatform titles.

On PS3, though, compromises were constant. Artists had to shrink texture sizes or cut detail because the GPU’s 256 MB simply wasn’t enough. Gameplay programmers, meanwhile, were fighting for their own half of the pie. It wasn’t just about raw horsepower—it was about the rigidity of Sony’s design.

The split memory pool became a quiet villain of the seventh generation, lurking behind many of the PS3’s weaker third-party ports. Only Sony’s internal teams, with time and resources to master the hardware, could consistently work around it. For everyone else, it was a headache that Microsoft didn’t force them to endure.

As a result, more and more studios prioritized Xbox 360 development. The workflow was easier, the tools were better, and the results looked great. For multiplatform games, the PS3 often received the “afterthought” version—buggier, blurrier, and less polished. Even some Japanese developers, traditionally PlayStation loyalists, began to hedge their bets with Microsoft’s console.

Cell vs. Game Devs

The Cell might have been a marvel of engineering, but in the trenches of game development, it was viewed less as a breakthrough and more as a nightmare.

Valve's Gabe Newell was blunt: “The Cell is a waste of everybody’s time. The PlayStation 3 is a total disaster on so many levels.” Valve temporarily stopped porting new games to the PS3, prioritizing the 360.

Id Software’s John Carmack admitted that the PS3 required significantly more effort to achieve the same results as the Xbox 360, calling its architecture “exotic” in the most unflattering way.

Some smaller studios often didn’t bother at all. With higher dev costs, longer cycles, and fewer sales compared to Xbox, the PS3 was a losing proposition.

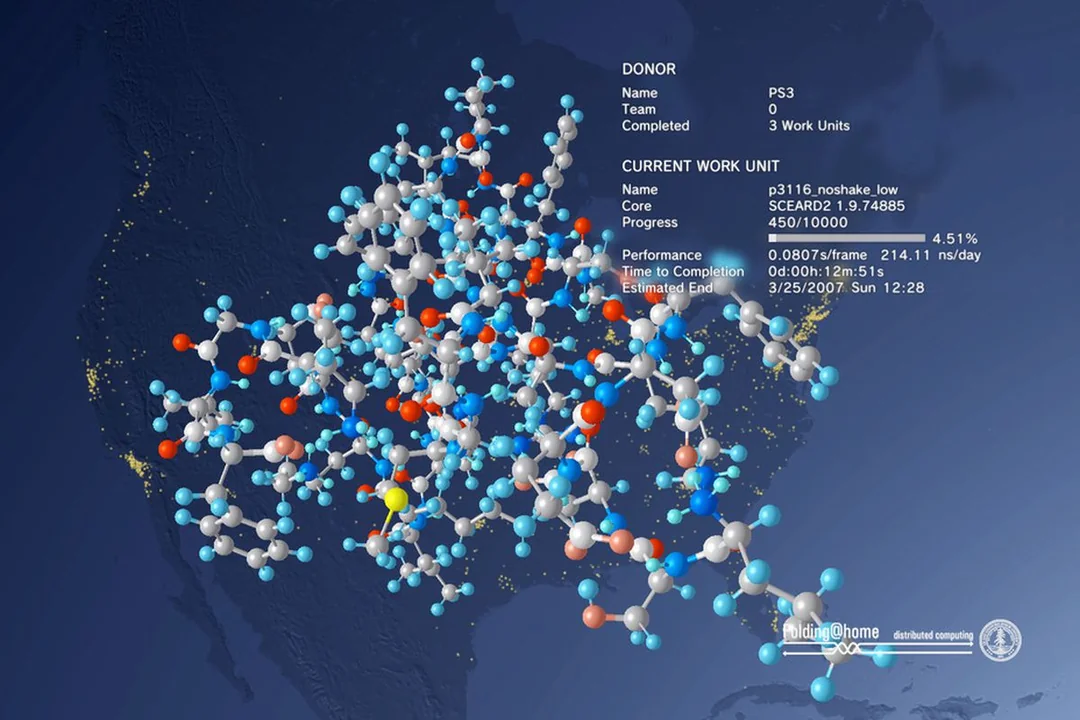

When Science Loved the PS3 More Than Gamers

While gamers grumbled about slow ports and clunky installs, scientists were buying PS3s in bulk. The Cell processor’s parallel computing abilities—so maddening for game developers—were a dream for researchers who needed raw number-crunching power on a budget.

At the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, astrophysicist Gaurav Khanna famously linked together a cluster of PlayStation 3s to simulate black holes and gravitational waves. The results were staggering: a handful of consoles outperformed over a hundred high-end Intel Xeon systems. Suddenly, what Sony had marketed as an entertainment hub was moonlighting as a low-cost supercomputer.

Other universities followed suit, using PS3 clusters for everything from molecular modeling to AI experiments. For labs strapped for funding, Sony’s troubled console offered an affordable back door into high-performance computing. It was one of the strangest ironies of the seventh generation: the PlayStation 3 was sometimes better at unraveling the mysteries of the universe than it was at running a multiplatform game smoothly.

In 2007, Sony did something no one expected from a game console: it turned the PS3 into a tool for global science. Through a free application called Folding@home, players could lend their console’s idle processing power to Stanford University’s protein-folding project. Instead of rendering Nathan Drake’s smirk, your PS3 could help researchers understand diseases like Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, and cancer.

At its peak, over a million PS3 owners joined in, creating one of the most powerful distributed supercomputers the world had ever seen. Together, they generated more raw computing power than even the fastest standalone machines of the era. For many gamers, leaving their PS3 humming overnight became a quiet act of charity—a way to fight disease from their living room.

It was a rare case where Sony’s extravagant Cell processor truly fulfilled its “for the greater good” potential. Ironically, while the PS3 stumbled in the gaming world, it was saving lives in the background.

The irony wasn’t lost on anyone: Sony had put a data-center-grade CPU in a gaming console, and researchers loved it more than gamers did. For scientists, the PS3 was affordable supercomputing. For developers, it was an overly complicated beast that made shipping multiplatform games a chore. It was almost as if the PS3 had been built for a different audience entirely—one that preferred lab coats to DualShocks.

Sony Fights Back

By 2007, Sony knew the PS3’s $599 stigma had to die. The first move was killing off the bare-bones 20GB model and slashing the 60GB version’s price tag. To sweeten the deal, an 80GB model hit shelves—bundled with MotorStorm in North America. It wasn’t enough to erase the launch fiasco, but it showed that Sony was listening.

One of the PS3’s killer features at launch was full backwards compatibility with the PlayStation and PlayStation 2 library. But that came at a cost—literally. As Sony wrestled with the PS3’s sky-high production costs, sacrifices had to be made. First, the Emotion Engine—the key component responsible for PS2 compatibility—was removed from newer PS3 models in favor of software emulation. Eventually, even that was scrapped. Later PS3 revisions dropped PS2 support altogether, leaving players with only PS1 backward compatibility.

This decision infuriated fans, especially those who had invested in the console under the assumption they could retire their PS2 without losing access to its library.Later models relied on partial software emulation, and then dropped PS2 support entirely. For many fans, it felt like a betrayal. For Sony, it was a necessary cut to make the console financially viable.

At launch, the PS3’s operating system felt more like a tech demo than a finished product. The cross-media bar (XMB) was sleek but barebones, the PlayStation Store was basically a clunky web page, and basic online functionality lagged far behind Xbox Live. For a $600 console marketed as the future of entertainment, it was an underwhelming reality.

But Sony chipped away at those shortcomings update by update. Firmware patches added long-requested features like in-game XMB access, customizable themes, and trophy support to rival Xbox achievements. Multimedia playback expanded too—suddenly the PS3 could handle DivX movies, stream content over DLNA, and double as a fully capable Blu-ray player with frequent updates to keep pace with Hollywood’s format.

As broadband speeds improved and consumer habits shifted, Sony doubled down on digital distribution. Full-fledged PS3 titles, expansions, and even PS1 classics became downloadable, eliminating the need for physical copies. It was a game-changer—literally. Suddenly, players could purchase a title and jump in within minutes, no trip to the store required.

This shift didn’t just impact major publishers. The PS3 played a crucial role in elevating indie games to mainstream recognition. While Microsoft had Xbox Live Arcade, Sony countered with PlayStation Network exclusives like Journey, Flower, and Super Stardust HD. These weren’t just filler between blockbuster releases—they were artistic triumphs, proving that a small development team could captivate players just as effectively as a multi-million-dollar studio.

Each update made the machine feel a little closer to the vision Ken Kutaragi had pitched back in 2005: a single device that could manage games, music, movies, and the internet. It was a slow grind, but by the end of its second year, the PS3 had evolved from a rough draft into the console Sony promised—just later, and harder, than anyone expected.

Blu-ray and the PS3’s Role in the HD Revolution

When the PlayStation 3 launched, it wasn’t just a gaming console—it was a trojan horse for the future of home entertainment. While gamers fixated on its raw power and exclusive titles, Sony had a bigger game plan: winning the high-definition format war. And they did just that.

At the time, the industry was locked in a fierce battle between Blu-ray and HD-DVD, two competing formats vying to become the standard for high-definition media. Microsoft and Toshiba backed HD-DVD, offering a cheaper alternative with an add-on drive for the Xbox 360. Sony, on the other hand, went all in, integrating a Blu-ray drive into every single PS3 unit. It was a bold, expensive gamble, but one that ultimately paid off.

With its ability to play Blu-ray movies right out of the box, the PS3 became an unexpected ambassador for the format. Movie studios took notice. Consumers, enticed by the prospect of a game console that doubled as a cutting-edge home theater device, started choosing Blu-ray over HD-DVD. The tipping point came in 2008, when Warner Bros. announced it was going Blu-ray exclusive, effectively sealing HD-DVD’s fate. By mid-year, the format war was over.

But the PS3’s multimedia dominance didn’t end there. Sony’s console became a living room staple, a machine that aged like fine wine thanks to constant firmware updates and an ever-growing suite of streaming services. From Netflix and Hulu to Spotify and YouTube, the PS3 evolved beyond gaming—it became a versatile entertainment hub long before the idea of “all-in-one” devices became commonplace. Even years after its successor arrived, the PS3 remained a go-to device for Blu-ray playback and digital streaming, proving that Sony’s forward-thinking strategy wasn’t just about games—it was about shaping the future of home entertainment.

The Golden Era of PS3 Exclusives

Sony had dominated the PlayStation and PlayStation 2 eras with one key advantage: exclusives that couldn’t be found anywhere else. From Final Fantasy to Tekken, the PlayStation brand was synonymous with must-play titles. But when the PlayStation 3 arrived, that grip started to loosen.

Enter the first-party studios. While Sony struggled to match the Xbox 360 in sales, it leaned hard on its internal development teams to keep the PS3 relevant. MotorStorm: Pacific Rift delivered chaotic, high-speed racing that showcased the PS3’s raw graphical power. Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune introduced players to Nathan Drake and laid the foundation for one of gaming’s greatest franchises.

But Sony wasn’t done. With LittleBigPlanet, Media Molecule crafted a whimsical, endlessly creative playground that encouraged players to dream big. Sackboy’s charming world was a canvas for imagination, with a robust level editor that birthed a thriving community of creators. It was more than just a platformer—it was a revolution in user-generated content, proving that games could be as much about creation as they were about competition.

By the early 2010s, the PlayStation 3 had completed its meteoric comeback, and the biggest reason for its resurgence? A tidal wave of jaw-dropping exclusives. Sony’s first-party studios had evolved from respected developers into genre-defining powerhouses, crafting experiences that pushed the industry forward and cemented the PS3’s place in gaming history.

At the forefront was Uncharted 2: Among Thieves, a masterclass in cinematic storytelling that made Nathan Drake a household name. Naughty Dog’s pulse-pounding set pieces, dynamic platforming, and razor-sharp dialogue elevated the game beyond a mere action title—it felt like playing through a Hollywood blockbuster. Ratchet & Clank Future: A Crack in Time reminded fans why the Lombax-and-robot duo was still one of the best in the business. Slowly but surely, Sony rebuilt its fortress.

Then came Gran Turismo 5, a love letter to car enthusiasts and a technical marvel that set a new benchmark for racing simulations. Featuring over 1,000 meticulously detailed cars, real-world physics, and stunningly recreated tracks, it wasn’t just a game—it was the closest thing to real driving without sitting behind a wheel.

These weren’t just great games. They were cultural milestones. Sony’s first-party studios—Naughty Dog, Santa Monica Studio, Guerrilla Games, and Sucker Punch—had grown into industry titans, setting a new standard for narrative-driven, technically ambitious gaming. The PlayStation 3, once ridiculed for its troubled launch, had transformed into a console synonymous with prestige gaming. It wasn’t about specs anymore. It was about experiences that left a lasting impact.

The Redemptive Power of the PlayStation 3 Slim

After fighting through tough competition and developer skepticism in the PS3’s early years, Sony needed a game-changer. They desperately needed something to erase the stigma of the infamous $599 launch and reposition the PS3 as the must-have console it was always meant to be. Enter the PlayStation 3 Slim, a leaner, more affordable, and power-efficient redesign that would finally shift momentum in Sony’s favor.

Gone was the bulky, glossy behemoth that had struggled to find mainstream appeal. The Slim was sleeker, lighter, and far less of a wallet-crusher, launching at a much more reasonable $299 price point. This wasn’t just a cosmetic change, though. Sony had streamlined the hardware, cutting power consumption nearly in half while maintaining the powerhouse performance of the original. Most importantly, it finally made the PS3 feel accessible.

And just like that, sales skyrocketed. Within three months of launch, Sony moved over a million units, and for the first time in the console’s life cycle, the PS3 was outselling the Xbox 360 in key markets. With a lower price, a growing library of must-play exclusives, and the Blu-ray format finally hitting its stride, the PlayStation 3 was no longer the underdog—it was a contender.

The PS3 Slim didn’t just revive consumer interest; it laid the foundation for Sony’s long-term strategy. It proved that a mid-generation refresh could reinvigorate hardware sales and reshape a console’s legacy. This lesson would later influence the Super Slim model that was released in 2012.

With Slim’s success, Sony had done the impossible. The PlayStation 3 was no longer the console that stumbled out of the gate—it was now the system that refused to stay down.

PlayStation Move: Sony’s Answer to Motion Gaming

By the late 2000s, motion gaming had taken the industry by storm. Nintendo’s Wii was a cultural phenomenon, and Microsoft was gearing up for Kinect. Sony, never one to sit idle, responded with PlayStation Move, a motion-control system that promised precision over gimmicks.

Armed with glowing orb-tipped controllers and PlayStation Eye camera tracking, Move was positioned as the next evolution in interactive gaming. Unlike the Wii’s infrared-based approach, Move utilized 1:1 motion tracking, delivering remarkably accurate movement replication in games like Sports Champions and The Fight: Lights Out. Hardcore gamers weren’t entirely convinced, but Sony made sure Move wasn’t just for casual play.

Despite its technical prowess, Move never reached the mainstream success of the Wii. The late arrival and a limited library of must-have exclusives kept it from dominating the motion-control scene. However, it wasn’t a failure—far from it. Move found a dedicated niche among fitness games, party experiences, and even first-person shooters. More importantly, it laid the groundwork for future advancements in motion-tracked gaming, with the controllers later repurposed for PlayStation VR on the PlayStation 4.

While Move may not have redefined gaming on the PS3, it was a bold experiment—one that proved Sony was always ready to innovate and challenge industry trends.

That should now properly reflect Move’s place in the PS3 era without any PSVR confusion. Thanks for catching that! Let me know if you’d like any further tweaks.

PlayStation Plus and the Birth of the Free Game Model

When PlayStation Plus launched in 2010, it was a tough sell. At a time when online play was free on PS3, many players questioned why they should pay for an optional subscription. But Sony had an ace up its sleeve—the Instant Game Collection, a concept that would redefine the value of gaming subscriptions for years to come.

The promise was simple but revolutionary: subscribe to PS Plus, and you’d get access to a rotating lineup of free games every month. Not watered-down indie shovelware, but full-fledged, critically acclaimed titles. Early adopters were treated to heavy hitters like inFamous 2 and LittleBigPlanet 2, setting the stage for what would become a beloved gaming tradition.

Over time, what started as a bonus incentive became a defining feature of PlayStation’s ecosystem. Gamers who initially subscribed out of curiosity quickly found themselves amassing a massive digital library at no extra cost. By the end of the PS3 era, PS Plus was no longer just an optional add-on—it was essential. Players didn’t just want it; they needed it.

Sony’s bold move with the Instant Game Collection had far-reaching consequences. It conditioned players to expect free games as part of a premium membership, paving the way for Xbox’s Games with Gold, the expansion of PlayStation Plus on future consoles, and the rise of modern services like PlayStation Plus Extra and Game Pass. What started as a simple perk on PS3 evolved into a blueprint for the future of gaming subscriptions.

The PS3’s Late-Generation Surge

For years, it seemed like the PS3 was destined to lag behind the Xbox 360. Microsoft had a head start, a lower price tag, and a well-established online ecosystem that gave it an undeniable edge. But if there’s one thing Sony has always understood, it’s the power of persistence. The PS3’s story wasn’t about instant success—it was about the long game.

By the time the console generation was winding down, something unexpected happened: the PlayStation 3 caught up. Despite its disastrous launch and years of playing second fiddle to Microsoft, Sony’s unwavering commitment to its platform paid off in spectacular fashion. The numbers tell the tale—by the end of 2013, the PS3 had surpassed the Xbox 360 in total global sales, proving that a strong finish can sometimes be just as important as a fast start.

So how did Sony pull off this improbable comeback? Exclusive games, relentless innovation, and a consumer-friendly strategy. As the generation matured, the PS3’s library became an undeniable force, stacked with industry-defining hits. Meanwhile, PlayStation Plus provided immense value, offering free games before subscription models became the industry norm.

Sony also embraced affordability. The PS3 Slim, and later the Super Slim, brought the price down to mass-market levels, making the console far more accessible. And unlike Microsoft’s fumble with Kinect’s forced integration, Sony kept its focus squarely on what gamers actually wanted.

By the time the PS4 launched, the PlayStation brand had fully regained its dominance. The PS3 had transformed from an industry underdog to a testament to Sony’s resilience and long-term vision. It was a hard-fought battle, but in the end, PlayStation had the last laugh.

The Legacy of the PS3

The PlayStation 3 was a trial by fire for Sony. But if there’s one thing history proves, it’s that adversity breeds innovation. Every misstep the PS3 took became a lesson. Every victory, a blueprint for the future. Through sheer persistence, a slate of unforgettable exclusives, and a mid-generation redesign that gave it a second wind, the PlayStation 3 turned its story around. It went from an industry punchline to a cornerstone of gaming history, outlasting the Xbox 360 in sales and setting the stage for Sony’s dominance in the generations to come.

The PlayStation 3’s journey was anything but smooth. It launched under the weight of sky-high expectations, brutal competition, and a price tag that sent wallets into cardiac arrest. It stumbled out of the gate, lost ground to a confident Microsoft, and struggled to justify its complex, developer-unfriendly architecture. It took time—too much time—but the Cell processor eventually went from a liability to a weapon. As developers adapted, it became clear: the PS3 was never underpowered—just misunderstood.

Time has only cemented its legacy. From its pioneering Blu-ray capabilities to its genre-defining exclusives, the PlayStation 3 didn’t just survive its early missteps—it transcended them. And that’s why, decades later, it remains one of the most significant and beloved consoles in gaming history.