In the mid-’90s, the gaming world was a two-horse race. Nintendo and Sega—titans forged in the crucible of the 8-bit and 16-bit eras—stood atop the industry like immovable colossi. Their loyalists were fervent. Their catalogs iconic. But just as the fifth generation loomed, with whispers of 3D graphics and multimedia convergence, an unexpected disruptor emerged from an entirely different arena: Sony. Yes, the same Sony known for Walkmans and Trinitron TVs.

The PlayStation didn’t just arrive—it detonated. With its matte-black boot screen, CD-based tech, and a swagger that screamed next gen, it didn’t play by the old rules. It redrew the map. Gamers who once argued over hedgehogs and plumbers were suddenly lining up to pilot futuristic racers, infiltrate enemy bases, and save the world in sprawling cinematic epics. And the ripples of what Sony started in 1994? They’re still being felt today.

From Revenge to Revolution

Sony’s road to gaming glory actually began with heartbreak. Nintendo, then at the height of its powers, sought to future-proof its empire with a CD-ROM add-on for the Super Famicom. Sony, riding high on a decade of consumer electronics dominance, was tapped to handle the disc-based technology. Behind closed doors, engineers from both sides hammered away at prototypes. Whispers of internal codenames, like “Super Disc,” filled the hallways.

The result was the SNES-CD project, with internal prototypes labeled “Play Station.” It was a chimera: a hybrid console that could play both SNES cartridges and a new “Super Disc” format. Sony saw an opportunity to control the emerging CD standard in gaming. Nintendo, however, saw something more dangerous: a partner becoming too powerful.

An internal memo from the time reportedly expressed concern that “Sony would control the software pipeline.” That was a line Nintendo, a company deeply protective of its licensing model, wouldn’t cross. In June 1991, at the height of anticipation, Sony confidently unveiled its SNES-CD prototype at the Consumer Electronics Show. But the celebration was short-lived. The very next day, Nintendo stunned the industry by announcing a new deal with Dutch electronics giant Philips.

This wasn’t a quiet corporate reshuffle—it was a public betrayal.

Howard Lincoln, then chairman of Nintendo of America, attempted to frame the decision as “in the best interest of consumers,” but the move sent shockwaves through the tech world. Nintendo had effectively walked out on Sony mid-project, stripping them of the ability to publish SNES-CD software and cutting them out of the very ecosystem they had helped build.

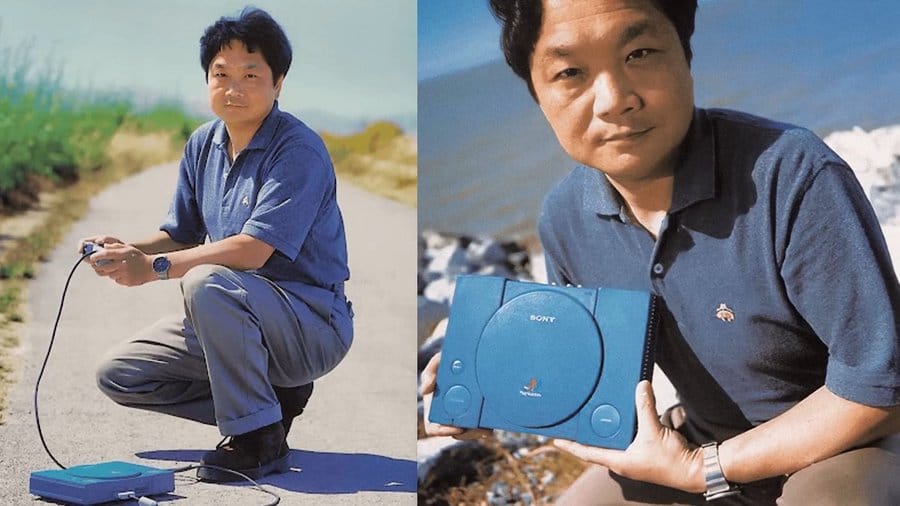

Sony’s then-President Norio Ohga and Ken Kutaragi, who is often dubbed the “Father of the PlayStation,” were stunned and understandably furious. A senior Sony exec reportedly said at the time: “They used us to get what they wanted, and then they walked.” Instead of backing down, Sony doubled down. Kutaragi was given the green light to rework the failed SNES-CD prototype into a standalone console.

The Birth Of PlayStation

What could have been a death knell for the project instead lit a fuse. Lesser companies might have retreated, licking their wounds, perhaps vowing to never dabble in the fickle world of video games again.

But this was Sony. And this was Ken Kutaragi. He was not a man to back down. Supported by executive Teruhisa Tokunaka and tucked safely under Sony Music’s wing, Kutaragi kept tinkering.

He argued passionately to Sony’s leadership: why develop groundbreaking CD-ROM technology just to let it power someone else’s console, especially a rival who had just publicly shamed them? Why not build their own machine? A machine that could leverage all of Sony’s technological prowess.

The project needed a name. Internally, it was still often referred to by its original concept: the “Play Station” (initially two words!). This name, simple and direct, stuck. Kutaragi’s team, small and fiercely dedicated, pressed on. They took the foundational CD-ROM technology they’d been developing for Nintendo and began to repurpose it. This wouldn’t be an add-on. This would be a standalone console.

The move to Sony Music was also strategically brilliant. Sony Music understood content, artist relations, and the fickle nature of youth markets – all things that would become crucial for the PlayStation’s success. They provided a more agile and less risk-averse environment than Sony’s traditional hardware divisions.

The betrayal had an unintended consequence for Nintendo: it pushed Sony to become a direct, powerful, and incredibly motivated competitor. The embers of the failed Nintendo partnership were fanned into the flames of a new, independent project.

The Dev Kit That Changed the Industry

Sony didn’t just build a console—they built a movement.

Sony’s acquisition of Psygnosis in 1993 wasn’t just a strategic grab for talent—it was a preemptive strike. A signal that the company wasn’t stumbling into gaming; it was preparing for total war.

At the time, Psygnosis was known for surreal box art and technically dazzling titles like Shadow of the Beast. They had cachet in Europe, a reputation for pushing hardware, and—crucially—a rebellious, Amiga-born sensibility. These weren’t suit-and-tie developers. They were rockstars with code.

Sony didn’t just want to make games. It wanted to understand how to make people want to make games—for their system. Psygnosis, with its eccentric crew and unorthodox methods, offered a gateway into the wild frontier of European development, where intuition often trumped process. Behind the scenes, though, something far more consequential was brewing: the dev kit.

Enter SN Systems. Formed by Martin Day and Andy Beveridge, the duo were already legends in the Britsoft underground. Their original claim to fame? A cross-compiler that allows PlayStation code to run on standard PCs. In 1994, this was sorcery.

Before PSY-Q, console dev kits were beasts—$20,000+ monsters that required proprietary hardware, reams of documentation, and often a degree in arcane engineering. Sony had initially pursued a similar path. Their early dev tools were clunky, expensive, and drenched in bureaucracy.

SN Systems flipped the script. With PSY-Q, developers could use a humble PC to build PlayStation software. It was fast. It was cheap. It worked.

No more waiting weeks for a dev station to ship from Japan. No more tiptoeing around corporate gatekeepers. Just plug in and build. For Sony, PSY-Q wasn’t just a cost-saver—it was a revolution in accessibility. That toolkit, packaged neatly with a Psygnosis smile, unlocked the door for hundreds of developers who couldn’t have otherwise afforded entry. In a single swoop, Sony went from exclusive to inclusive.

Las Vegas, January 1994. CES was loud, chaotic, and full of hype—basically the perfect stage for Sony’s coming-out party. In a darkened booth, obscured from the main floor, was a tech demo built in part using SN Systems’ tools. It wasn’t flashy. It wasn’t even a full game. But it was fast. Smooth. Polished in a way that seemed alien compared to the choppy 3D demos Nintendo and Sega were still fumbling with.

One executive—still skeptical about this whole “PlayStation” idea—stood in silence, watching polygons glide effortlessly across the screen. No expensive silicon. No custom dev rig. Just a PlayStation board, running clean, stable code off a PC.

That was it. The moment. The demo didn’t just seal the deal internally—it redefined what a next-gen console could look like. Suddenly, Sony wasn’t the underdog anymore. It had tools. It had a vision. And it had developers on their side.

The result? A tidal wave of creativity. While Sega and Nintendo kept their kingdoms tightly guarded, Sony flung open the gates. Sony’s bet on openness transformed the console from a closed garden into a creative playground. And players got to reap the rewards. And at the heart of it all? A dev kit. A company called SN Systems. And a left-field acquisition that turned out to be one of the most quietly brilliant moves in gaming history.

A New Standard in Audio and Visuals

While Nintendo and Sega tiptoed into the 3D era with one foot still rooted in the pixelated past, Sony charged forward with a machine designed from day one to handle full-blown, real-time 3D. No smoke, no mirrors. The PlayStation was engineered to ditch the sprite sheets and bring polygonal worlds to life—gritty, jagged, ambitious worlds that felt unlike anything that had come before.

This wasn’t about layering clever tricks over 2D engines. This was a tectonic shift. The kind that separates generations. Developers could now build games with depth—literal, spatial depth. Instead of characters moving across flat planes, they could now run around corners, explore three-dimensional landscapes, and interact with a dynamic camera.

And it wasn’t just about looking impressive. It felt different. Games moved with a new kind of weight. A new kind of freedom. The PlayStation didn’t just offer 3D as a novelty—it made it the new normal. And there was no going back.

In the mid-’90s, cartridges were clinging to their final breath. Limited storage. High manufacturing costs. Slower turnaround times. For developers with big ideas and bigger stories, they were becoming a creative straitjacket. Then came the PlayStation, armed with the humble yet mighty CD-ROM—a format borrowed from the music industry, but weaponized for gaming.

Each disc offered up to 650MB of storage. That’s not just more space—that’s orders of magnitude more room for imagination. Entire orchestral soundtracks. Pre-rendered cutscenes. Fully voiced dialogue. Developers could finally stretch out, breathe, and build games that felt cinematic, expansive, and deeply immersive.

Redbook audio turned gaming soundtracks into albums. Lush, orchestrated scores. Thumping techno. Grimy industrial rock. Game music wasn’t background noise anymore—it grabbed you by the ears and held on.

And voice acting? No longer a gimmick. It became a narrative staple. Sure, it was rough around the edges, but hearing characters talk—like, really talk—changed player immersion forever. Suddenly, games had nuance, personality, emotional punch.

Then came the visual sizzle. Pre-rendered cutscenes and full-motion video weren’t just eye candy—they were event markers. Final Fantasy VII’s cinematic moments felt like watching a blockbuster unfold. These games had scope, drama, and flair that no cartridge-based system could dream of. The PlayStation wasn’t just a step up—it was a leap into the future of how games could sound and look.

Japan Launch of the PlayStation

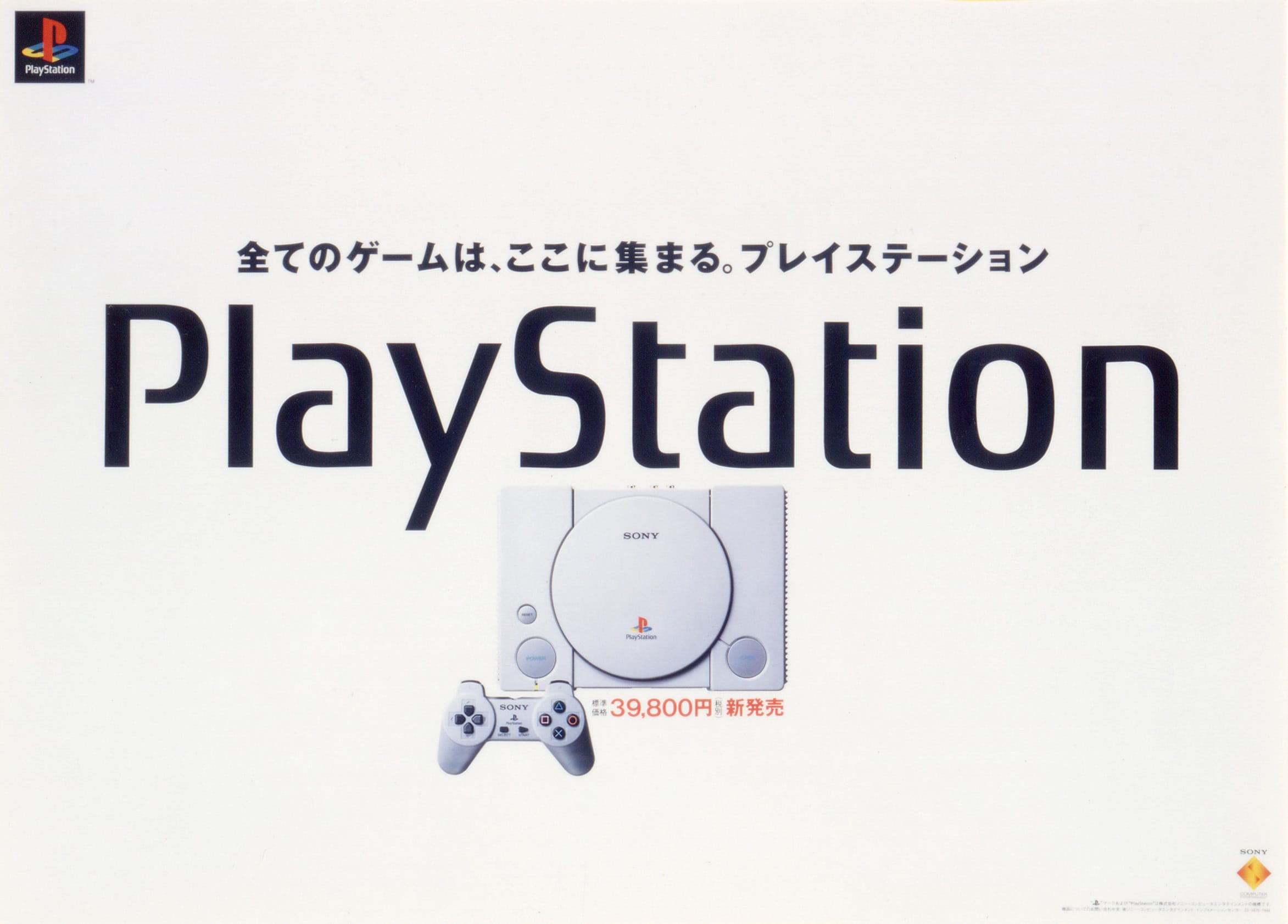

December 3, 1994. Frost clung to the windows of Tokyo’s streets, yet outside major retailers, the air buzzed with anticipation. Huddled in thick coats, gamers formed long, winding queues—each person hoping to be among the first to cradle Sony’s bold new machine: the PlayStation.

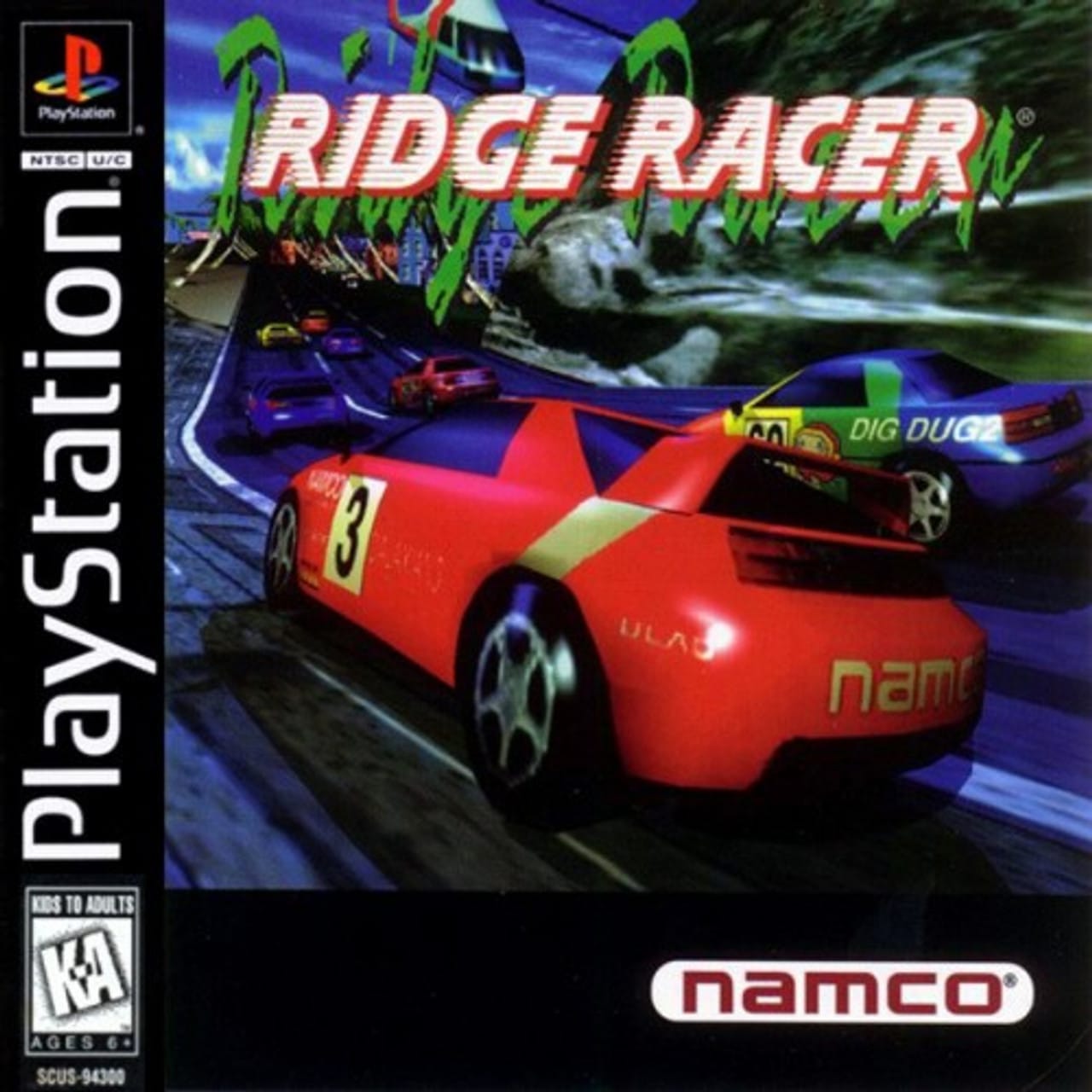

When doors opened, the console sold with the urgency of a rare concert ticket. At ¥39,800, it wasn’t cheap, but it felt like the future. The launch lineup featured eight games, but one title in particular made jaws drop. Namco’s Ridge Racer wasn’t just a racer—it was an arcade dream reconstructed, pixel for pixel, in the living room. The loading screen even let players control a tiny Galaxian ship, a playful reminder that this was a console with personality.

Sony’s debut numbers were nothing short of impressive. Selling 100,000 units on launch day and 300,000 by the end of December was a clear statement: people were ready to take this newcomer seriously. For a company with no gaming pedigree, it was a remarkable feat. Families, teenagers, and early tech adopters all clamored for a chance to try something that felt sleek, modern, and distinctly different from what Nintendo or Sega had offered before.

Yet in the same breath, reality set in. Sega’s Saturn had launched just weeks earlier on November 22, 1994, and it was already sprinting ahead with a head start. Anchored by Virtua Fighter, a jaw-droppingly accurate arcade port, the Saturn shifted more than half a million units in its opening stretch in Japan. Sega had home turf advantage and years of industry experience, and for the moment, that advantage showed.

The PlayStation wasn’t out of the race—it was very much in it—but Sony wasn’t leading the pack yet. In late 1994, the fifth generation of consoles looked like Sega’s to lose. Sony had planted its flag in the ground, but the true battle for living rooms worldwide was only just beginning.

The First E3: Sony’s Strategic Showcase

Until 1995, video games had lived in the shadow of the Consumer Electronics Show—a sprawling tech carnival where new hardware and software were often drowned out by bigger, flashier gadgets. By the mid-’90s, the industry had outgrown that cramped corner of CES. Games weren’t side attractions anymore; they were billion-dollar cultural engines demanding their own spotlight.

Enter the Electronic Entertainment Expo. From May 11 to May 13, 1995, more than 50,000 people swarmed the Los Angeles Convention Center for the inaugural E3. For the first time, gaming wasn’t sharing space—it was commanding it. Publishers set up extravagant booths, developers showed off ambitious new titles, and journalists scrambled to make sense of the tidal wave of announcements.

But the real story was the console war on full display. Sega, Nintendo, and Sony each rolled into the convention with something to prove. Sega flaunted the Saturn, Nintendo teased the long-awaited Ultra 64, and Sony prepared to make the PlayStation impossible to ignore.

Sony arrived at E3 with a clear message: this wasn’t just another console launch. This was the evolution of an entertainment empire. The presentation opened not with gameplay or flashy graphics, but with a retrospective reel—Walkmans, compact discs, camcorders, the products that had already reshaped music and media consumption around the world. Each clip built momentum until the PlayStation logo finally appeared, framed as the natural next step in Sony’s legacy of innovation. It was subtle, but powerful. If Sony could redefine how people listened to music or watched movies, why couldn’t it also define how they played games?

When Sony Computer Entertainment’s president Olaf Olafsson took the stage, the energy shifted. Gone were the slick highlight reels and pop-culture gloss—this was all business. In a calm, deliberate tone, the Icelandic executive laid out Sony’s strategy for entering an industry that had long been dominated by Sega and Nintendo.

Rather than diving into game footage or technical demonstrations, Olafsson spoke about market opportunities, hardware advantages, and the value Sony saw in positioning the PlayStation as more than just a console. He emphasized partnerships with developers, the cost-effectiveness of CD-based media, and the scalability of the platform. It wasn’t flashy, but it was calculated—a blueprint for how Sony planned to not just compete, but thrive.

By modern standards, it was an oddly restrained presentation. No celebrity cameos, no bombastic slogans—just a steady case for why Sony had the resources and foresight to lead the next generation.

As Olaf Olafsson wrapped up his measured remarks, the stage was handed to Steve Race, the newly minted president of Sony Computer Entertainment America. Race had a full speech prepared, but instead of delivering pages of corporate jargon, he walked to the microphone, paused, and spoke just two words and three numbers:

“Two ninety-nine.”

The crowd erupted. That was it—no slides, no buildup, no explanation needed. Everyone in the room already knew Sega had priced the Saturn at $399, a figure that raised eyebrows just weeks before. By undercutting Sega by a full hundred dollars, Sony had landed a knockout blow without breaking a sweat.

It was more than a price announcement. It was a moment of theater, a line destined to be replayed in gaming history reels for decades to come. In just three syllables, Race communicated confidence, aggression, and accessibility. The PlayStation wasn’t just competitive—it was disruptive. And in that instant, the balance of power in the fifth-generation console war began to tilt.

If Steve Race’s “$299” quip was the tactical strike, Michael Jackson’s surprise appearance at Sony’s booth was the cultural haymaker. The King of Pop casually strolling through the PlayStation display was more than celebrity spectacle—it was a declaration that Sony was plugged into the beating heart of global culture.

Jackson, who had previously collaborated with Sega on Moonwalker and even contributed music to Sonic the Hedgehog 3, was now seen leaning over PlayStation kiosks, controller in hand. The symbolism was impossible to miss: Sega had once courted him, but Sony had captured his attention when it mattered most.

For attendees, it was electrifying. For the press, it was gold. The images of Michael Jackson with Sony hardware ricocheted across newspapers and TV spots, transforming the PlayStation from a promising console into a bona fide cultural event. In a single afternoon, Sony proved it wasn’t just competing with Sega and Nintendo on technical specs—it was redefining gaming as part of the mainstream entertainment landscape.

North American and European Launch

September 9, 1995. When the PlayStation finally hit North American shelves, the buzz from E3 hadn’t died down—it had intensified. Priced at the headline-grabbing $299, the console arrived in a simple box: one machine, one controller, the hookups, and nothing more. Unlike Sega or Nintendo, Sony skipped the traditional pack-in game, a calculated move to keep the price sharp and let players decide which experience would define their new system.

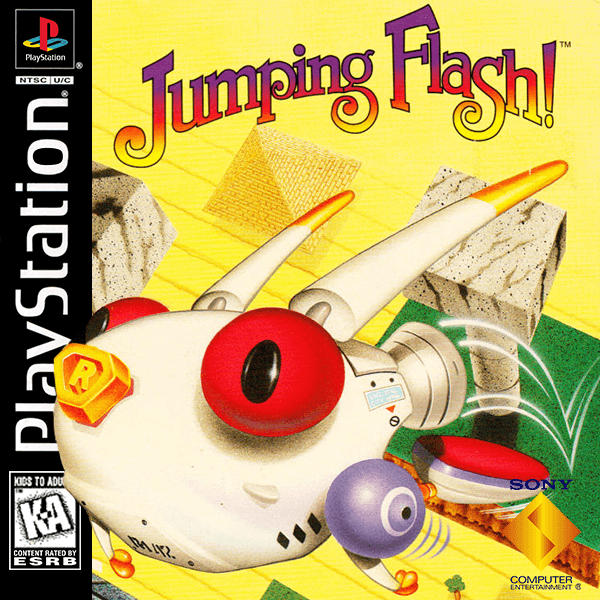

Sony understood that powerful hardware meant nothing without the software to back it up. And when the console launched in Japan a year before, it did so with a clutch of games that didn’t just showcase the tech—they set the tone for an entire generation.

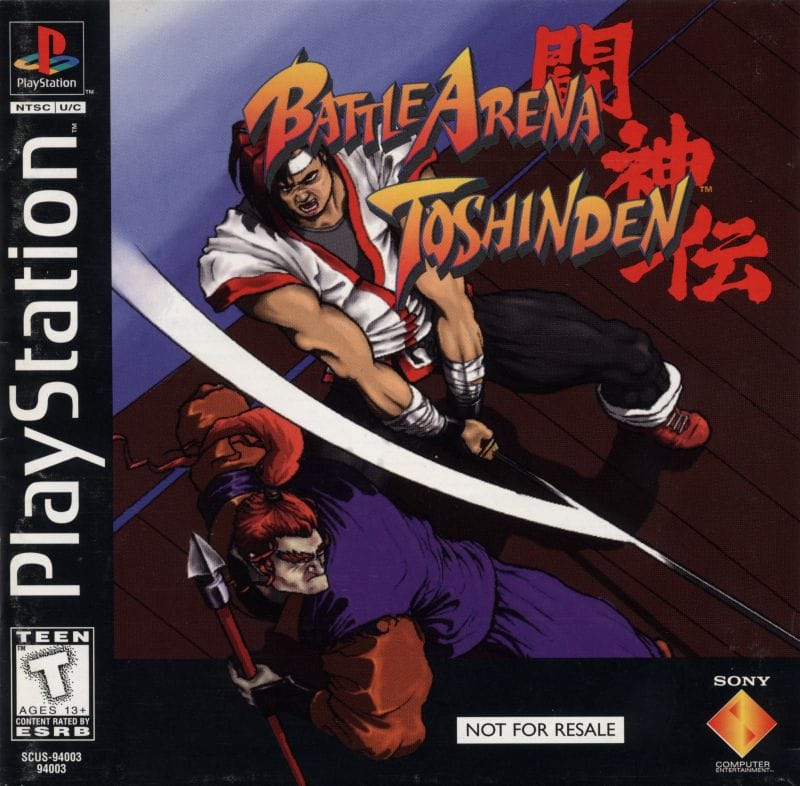

Day-one buyers had ten titles to choose from, a mix that showed Sony’s intent to appeal to every type of gamer. Battle Arena Toshinden teased flashy 3D fighting, Rayman offered a colorful platforming option, while Ridge Racer was the undeniable showcase of what the PlayStation could do. These weren’t ports with the rough edges sanded down. They were launch titles that felt tailor-made for the platform—flashy, loud, and bursting with possibility.

Sega had entered the American market with a surprise move, dropping the Saturn months ahead of schedule in May 1995. The gamble was meant to give them a head start, but it backfired spectacularly. Retailers were caught off guard, the launch lineup was thin, and the $399 price tag left many players cold. By the time Sony’s PlayStation arrived in September, the field was wide open.

Within just two days, the PlayStation had outsold the Saturn in the United States. Two days. It wasn’t just a sales victory—it changed the market’s perception of who held the momentum. Sega’s once-commanding presence in arcades and living rooms suddenly looked fragile, while Sony’s slick machine was the one everyone wanted to try.

The difference came down to execution. Sony didn’t rush its launch; it built hype through E3, locked in a competitive price, and ensured a broad range of games were on shelves day one. Where Sega stumbled, Sony sprinted. That early win in North America gave the PlayStation the foundation it needed to become a household name—and set Sega on the slow, painful road away from hardware dominance.

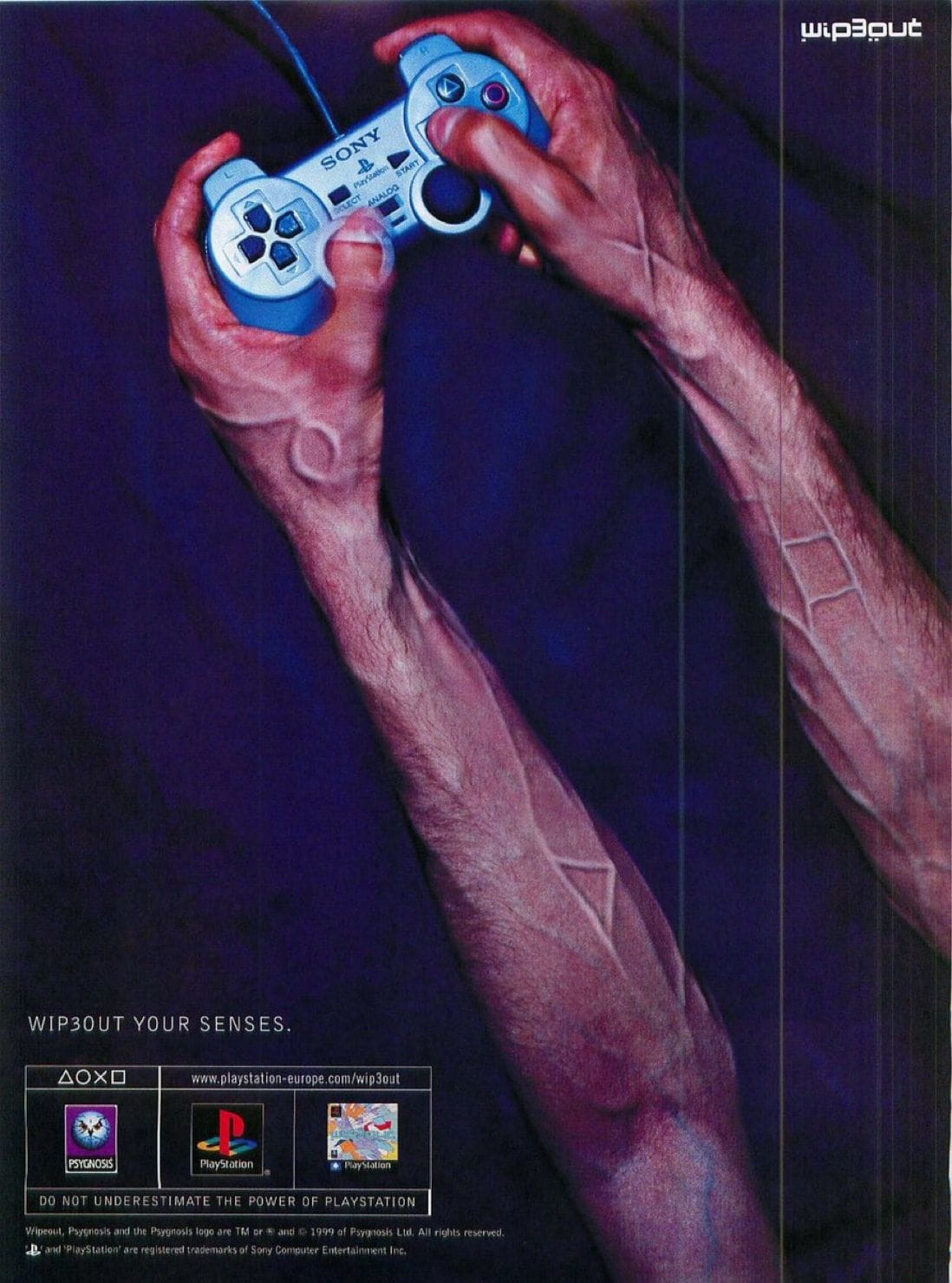

September 29, 1995. Just weeks after its North American debut, the PlayStation crossed the Atlantic, officially launching in Europe. The lineup wasn’t as stacked as in the U.S., but it didn’t matter—Sony had two aces up its sleeve. Ridge Racer was there, as slick and pulse-pounding as ever, but it was WipEout that truly set the tone for the region.

Developed by Liverpool-based Psygnosis, WipEout wasn’t just a futuristic racer—it was a statement. With its thumping techno soundtrack, sharp-edged design, and marketing campaign that plastered PlayStation ads in nightclubs and on billboards, the game embodied a distinctly European flavor of cool. In the UK especially, WipEout became synonymous with the PlayStation itself, transforming Psygnosis into a household name and proving that Sony understood local audiences better than its rivals.

The results were immediate and devastating for Sega. By the end of the 1995 holiday season, the PlayStation was outselling the Saturn three-to-one in the UK. Parents saw it as the must-have gift of the season. Teens and twenty-somethings who might have dismissed video games as “childish” suddenly saw the PlayStation as an extension of their identity. Developers saw the PlayStation as the platform where their games would reach the biggest audience.

Game Library Goldmine: Hits That Defined a Generation

When Final Fantasy VII landed in 1997, its thunderous marketing blitz, breathtaking FMVs, and a sprawling narrative about eco-terrorism and existential dread turned heads in the West. Sony’s cinematic campaign placed Final Fantasy VII alongside Hollywood blockbusters. And players responded. Millions bought the game who had never touched a role-playing title before. They got lost in Midgar, cried in the Forgotten Capital, and learned that turn-based battles and menus could be utterly electrifying. This wasn’t niche anymore. It was mainstream.

Then came Gran Turismo. Not loud, not flashy—just meticulous. A gearhead’s dream rendered in bleeding-edge polygons. It wasn’t just about racing. It was about respect for the machine. Every engine hum was authentic. Every car handled with real-world physics. And with its dual-mode format—arcade thrills and simulation purism—it catered to both casual drivers and obsessive tuners. You could lose hours just tweaking your suspension. This was more than a racing game. It was a love letter to automotive culture. One that sold more PlayStations than some consoles sold games.

With faster pacing, sidestepping, and an absurdly stylish roster, Tekken 3 wasn’t just a fighting game—it was a cultural moment. Eddy Gordo’s capoeira spins? Iconic. Hwoarang’s taekwondo flurries? Instant muscle memory. Even casual players could mash buttons and feel like virtuosos. Tekken 3 showed that 3D fighters had legs outside the arcade.

Of course, not everything was polygonal bravado and grit. Sometimes, greatness arrived with a paper-thin beat and a rapping dog. PaRappa the Rapper was weird, bright, charming. Its call-and-response rhythm gameplay was basic by modern standards—but the soul? Unmatched. It radiated positivity. It taught you to believe. “I gotta believe!” became a mantra.

And then there was Vib Ribbon. A fever dream of vector graphics and surreal soundscapes. It let you insert your own CDs, generating levels from your personal music collection. Nobody else was doing this. Nobody else could. This game whispered something that would later become a roar: rhythm games matter. They’re not a gimmick. They’re pure expression.

The PlayStation didn’t rise to dominance on hardware alone—it was the software alliance that truly changed the game. Sony didn’t just open the doors to developers; they rolled out a velvet carpet. And the industry’s biggest names came flooding in.

Namco, Konami, Square, Capcom—these third-party studios found something with Sony they hadn’t felt in years: freedom. No restrictive licensing. No cartridge constraints. Just open arms, CD-ROMs, and the promise of reaching millions.

Square’s move was massive. When Final Fantasy VII went PlayStation-exclusive, it was a blow to Nintendo so powerful it echoed for years. Capcom brought Mega Man Legends. Konami dropped Suikoden ll. Namco kept arcades alive at home with Tekken, Ridge Racer, and Time Crisis. These weren’t just good games—they were industry-defining.

And presiding over it all, like a denim-clad jester of chaos—Crash Bandicoot. He wasn’t supposed to be Sony’s mascot. But with his Looney Tunes energy, expressive animations, and those unforgiving platforming gauntlets, he became the PlayStation’s face. Crash was fun incarnate. He spun, belly-flopped, and yelped his way into the hearts of millions. His games pushed the PS1’s hardware with clever camera tricks and vibrant worlds that felt alive. He wasn’t trying to be cool—he just was.

Together, these games didn’t just fill shelves—they forged identity. The PlayStation was no longer the new kid. It was the tastemaker. The trendsetter. The cultural lodestone of late-’90s gaming. And while Sega and Nintendo wrestled with proprietary formats and control, Sony gave developers the tools and space to thrive. It flipped the power dynamic. Suddenly, platform holders weren’t the stars—developers were.

And where did the best ones go? PlayStation. Every time.

Accessories: Changing the Way We Played

Just as important as the console itself were the little extras that came with it. Sony understood that the PlayStation wasn’t just about games—it was about reshaping how players connected with them. Gone were the days of passwords scribbled on crumpled scraps of paper. Passwords were a ritual. A pain, yes—but also a badge of honor. A string of hieroglyphs scrawled into a notebook, memorized by heart, or whispered to friends on the playground. Forget one symbol and it was back to the start. But the PlayStation said no more. It gave us memory cards.

Small, gray, and deceptively light, these eight-block marvels changed the rules. For the first time, saving a game wasn’t a backend system—it was a player-facing mechanic. You chose when to save. You felt the gravity of that choice. Want to try the final boss without grinding 30 hours again? Just slot in that little rectangle and load your progress. It was freedom. It was permanence. And it made gaming feel personal. Like your story was being written.

And when friends came over? You brought your memory card. Not just for saves—but for identity. Your car in Gran Turismo. Your created wrestler in WWF SmackDown!. Your absurdly broken party in Final Fantasy VII. This wasn’t just hardware. It was emotional storage. All suddenly manageable, portable, and personal. It was liberation. And it turned long-form gaming into a lifestyle.

Then there was the link cable, a deceptively simple accessory that unlocked a wholly new experience: two consoles, two TVs, two players facing off without compromising their screen real estate. For racing fans or fighting game diehards, it was a revelation—arcade-style competition in the comfort of a living room, but bigger, louder, and more personal.

The original PlayStation controller was a sleek riff on the SNES pad—no frills, all function. But 3D gaming was demanding more. Enter the Dual Analog Controller, and soon after, the juggernaut: the DualShock. The left stick gave precision; the right, camera control. Suddenly, character movement became fluid. Natural. You weren’t nudging a sprite—you were inhabiting a space.

The D-pad and four face buttons gave devs a familiar layout—but the addition of four shoulder buttons? That was a canvas. Racing games like Ridge Racer Type 4 mapped acceleration and braking to L2 and R2, giving players analog-like finesse before triggers were even a thing. When you were drifting corners, the controller became an extension of you—your hands, your instincts, your reactions.

Ape Escape, often overlooked but quietly revolutionary, was the first title that required analog control. It forced players to learn a new language. One stick to move, the other to swing your net. Clumsy at first. Then, essential.

Then the rumble hit. Whether it was a boss slamming the ground or a car kissing the guardrail, the DualShock spoke to your hands. Subtle tremors. Violent jolts. Each one a signal: Pay attention. Something’s happening. This rumble feedback suddenly made explosions feel like explosions.

Games weren’t just seen and heard anymore. They were felt. This wasn’t just an iterative redesign—it was a tactile revelation. It set a new gold standard. A design so intuitive, so future-proof, that its descendants are still with us today. Sony didn’t just hand players a new console—they re-engineered the relationship between player and game. And nothing was ever quite the same again.

Marketing Genius: Cool, Edgy, and Grown-Up

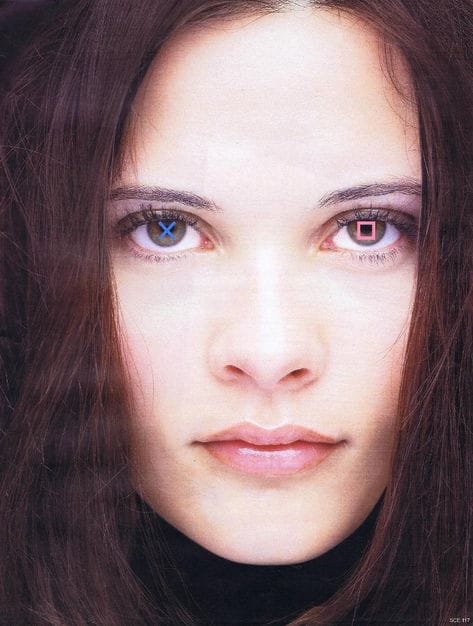

By the mid-to-late ’90s, Sony wasn’t just selling a console—it was selling a state of mind. And it all started with three words: UR NOT E. Cryptic. Confrontational. A little bit punk.

The “UR NOT E” campaign dared players to see gaming as rebellion. Not a childish pastime. Not something tucked away in a bedroom. This was edge. This was music-video swagger filtered through grayscale ads, cyberpunk fonts, and cryptic TV spots that looked like they belonged on MTV at 2 a.m. rather than during Saturday morning cartoons.

It was the anti-Nintendo manifesto. And it worked.

Where Nintendo stayed safe and Sega clung to its arcade roots, Sony zeroed in on the MTV generation. Their ads weren’t just commercials—they were mini manifestos. Trippy visuals. Cryptic slogans. A tone that screamed rebellion, attitude, and late-night house parties. The PlayStation wasn’t for kids. It was for you.

Meanwhile, over in the suburbs, Crash Bandicoot was getting in someone’s face—literally. In a move that felt both absurd and brilliant, Sony sent a guy in a Crash costume, armed with a bullhorn, to Nintendo HQ. He shouted challenges across the parking lot. Called out Mario. Danced around like a caffeinated gremlin. It was aggressive. It was loud. It was… undeniably funny. That megaphone moment said everything without saying much: PlayStation was here to disrupt. To poke the bear. To shake the snow globe.

Sony spoke the language of late-’90s cool in the U.S. and Canada. As grunge faded and hip-hop rose, and as technology began to merge with fashion, the PlayStation slid effortlessly into that cultural slipstream. It didn’t feel imported; it felt homegrown, resonating with a generation seeking new forms of entertainment and self-expression.

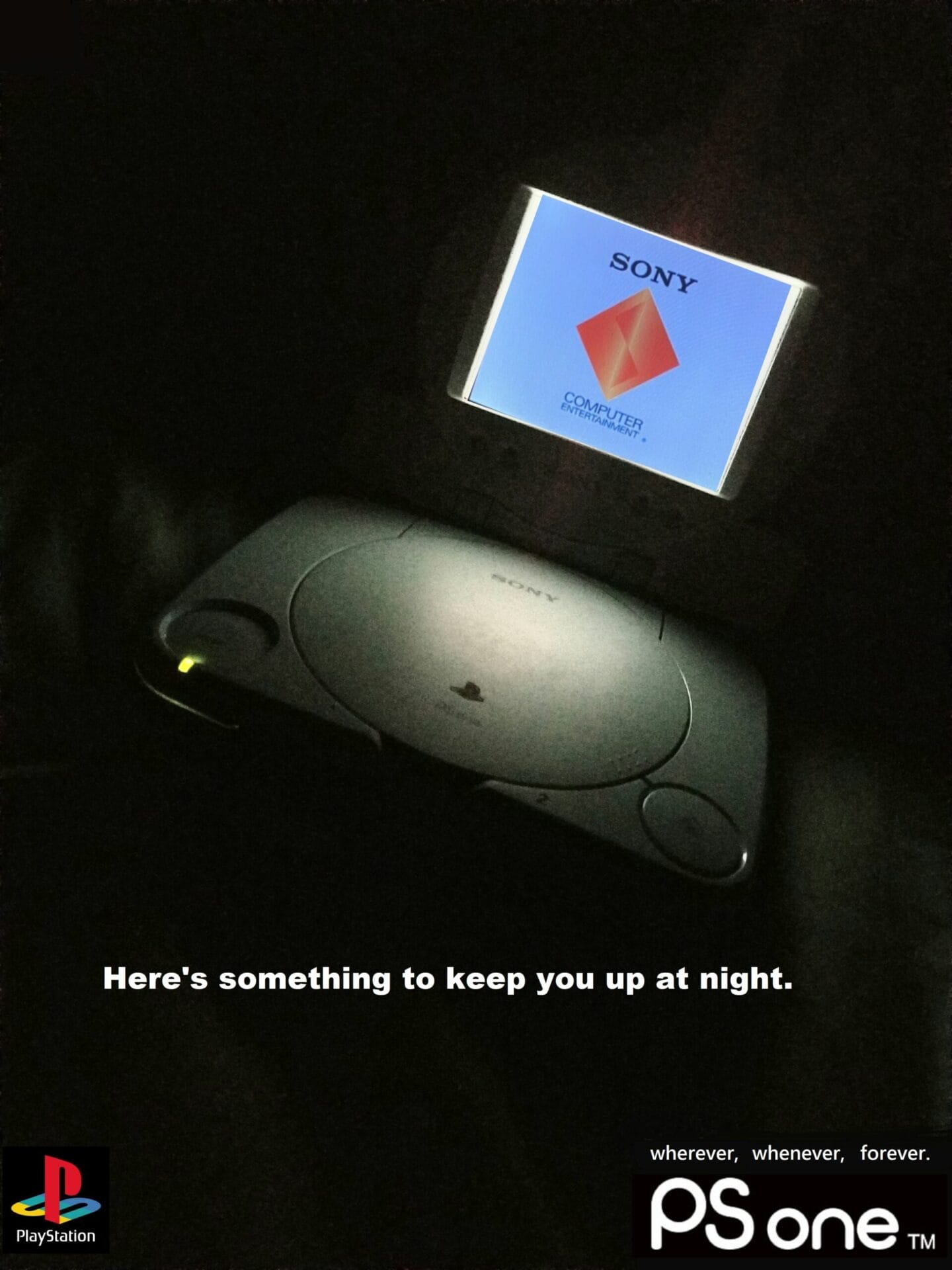

But Sony didn’t conquer just one region. It took over the entire planet, adapting its marketing for different cultural landscapes. For the UK launch, the company poured an eye-watering £20 million into marketing—an unprecedented figure for the time. The campaign blanketed television, magazines, billboards, and even club venues, ensuring that the PlayStation wasn’t just seen as a gaming console but as a cultural phenomenon.

Sony courted the club scene. A young marketing whiz named Geoff Glendenning, who joined in 1994, masterminded a guerrilla-style blitz to the generation sneaking into nightclubs, trading mixtapes, and buying their first CD players. WipEout was the spearhead of this approach. Its futuristic tracks, blistering speed, and thumping soundtrack from acts like The Chemical Brothers and Orbital gave the game an instant underground credibility.

PlayStation kiosks started showing up in chill-out rooms at techno events in Europe. You’d be halfway through a bass-heavy night in Manchester or Berlin and stumble across a PlayStation hooked up next to a lava lamp and a bean bag. By 1997, there were 52 official PlayStation rooms in UK nightclubs alone. Sony didn’t try to be the main event. It became the backdrop to youth culture—a low, constant frequency in the lives of the people who mattered most: trendsetters.

And then came the PlayStation Rooms. Part showroom, part lounge, part futuristic temple to interactive cool, these physical spaces blurred the line between gaming, art, and nightlife. Neon lighting. Minimalist décor. Curated playlists. They weren’t stores. They were vibes. You could demo a game, then sip a cocktail. Talk to a DJ. Maybe even buy a copy of Wipeout 2097 on vinyl. It was gaming, but elevated. Gaming without the stigma.

While a tougher nut to crack due to entrenched domestic competition, Sony was not an outsider in Japan. With heavy hitters like Square and Namco firmly in their corner, the console carved out a colossal domestic presence. Titles like Gran Turismo and Tekken were not just hits; they were groundbreaking, demonstrating Sony’s ability to cater to its home market’s high standards for innovation and quality.

What made it all work? Flexibility, as well as a deep understanding of what each market craved. While rivals stuck to their playbooks, Sony adapted, localized, and listened. The result? A console that didn’t just sell globally—it belonged globally. One where taste, style, and interactivity came together. And if you didn’t get it? Well… UR NOT E.

Piracy and the Grey Market

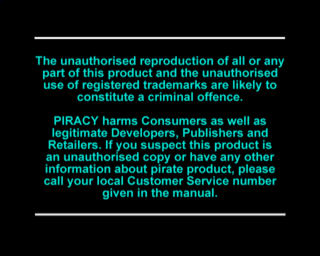

Let’s not tiptoe around it—piracy played a massive role in the PlayStation’s global saturation. The console’s use of CDs, while revolutionary, also cracked the door wide open for modding, duplication, and a roaring underground market. Sony knew that crackers would be snooping around the internals of the system to find ways to pirate games.

To combat this, they came up with a simple but clever method to protect their software from any form of backup. At the mastering plant, Sony implemented a ‘wobble groove’ on the inner rim of every PlayStation disc. The ‘wobble groove’ was read at boot up to determine the region encoding of the game, as well as to force the copy protection on the disk.

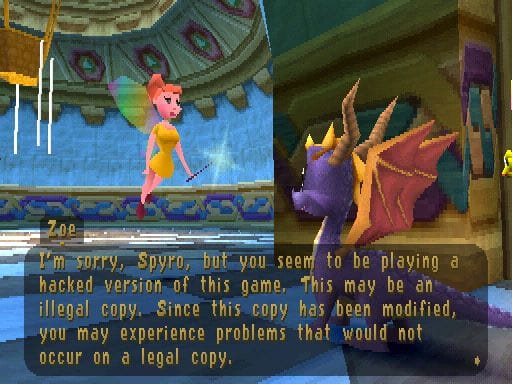

Once detected, players reported all types of game crashes, warning screens, and even messages from game developers. It was a clever system. You couldn’t burn this wobble onto a blank CD-R with a home burner. On top of that, most people didn’t even have CD burners to begin with when the PlayStation launched. In theory, Sony had won.

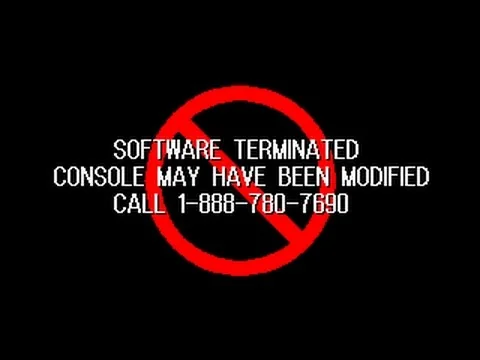

Spoiler alert: they hadn’t. The first loophole was by taking advantage of Sony’s inexperience with CD protection. All you had to do was insert a genuine PlayStation disk, quickly swap it with a CD backup, and force the lid open with a pen or paperclip so that the system thought the lid was closed. There was no encryption on these disks at all, and prices on CD burners soon began to plummet, making it easier for many to play backup copies of games. But the swap trick was a hassle. It was hard on the laser, hard on your discs, and required the timing of a bomb disposal expert. The scene needed a more elegant solution.

Enter the modchip—a tiny piece of silicon mischief that turned the PS1 from a closed ecosystem into a gateway to an entire shadow library. With a backup disk that was inserted into the PlayStation, the modchip essentially injected the correct data into the data stream from the CD reader, so that games looked legitimate. It was cheap. Easy to install. And it transformed the console into a haven for bootlegs, fan translations, and imports.

Piracy was so rampant that in Southeast Asia, South America, Eastern Europe—regions often sidelined by official distribution—piracy became the way to play. Street vendors peddled games in plastic sleeves. Entire storefronts stocked nothing but unofficial titles. You could even buy high-quality bootleg disks that worked like genuine PlayStation games, because their custom CD burners have now replicated the “wobble groove” perfectly.

During this boom of piracy, legendary warez groups like Callisto, Paradox, MUPS, and B.A.D. became infamous. Their mission: to be the first to “crack” a new game, strip out any protection (like the later, more advanced LibCrypt security used in games like Spyro: Year of the Dragon and Spider-Man), compress it, and upload it to hidden FTP sites and bulletin board systems (BBSs) around the world. Their digital “cracks” would then be downloaded, burned onto CD-Rs, and distributed through the vast global network of street vendors. It was a supply chain that was arguably more efficient than Sony’s own.

Of course, publishers lost revenue. For every kid who bought a bootleg copy of Tekken 3, Namco lost a sale. But Sony? They gained reach. Bootlegs moved hardware, and even grey markets built fanbases. The PlayStation’s ubiquity wasn’t just the result of retail strategy—it was a cocktail of street smarts, tech loopholes, and a disc format that couldn’t be contained. It was messy. It was controversial. But it made the PS1 inescapable.

Why PS1 Nostalgia Is Thriving

Time hasn’t dulled the PlayStation’s edge—it’s only sharpened its mystique. The PS1 is no longer just a relic of the ’90s; it’s a living, breathing obsession. In online forums, collector circles, and modding communities, the passion for Sony’s first console burns brighter than ever.

You can see it in the cottage industry of PS1 modders resurrecting old hardware with HDMI ports, region-free drives, and solid-state upgrades. You can feel it in the meticulous fan projects—like the Final Fantasy VII HD mods—that preserve, enhance, and reimagine the classics. These aren’t just nostalgia trips. They’re love letters.

Even Sony has dipped back into the archive, albeit clumsily. The PlayStation Classic might have missed the mark with its oddball game selection and emulation quirks, but it proved there’s appetite. Craving. An itch to revisit the era of boot-up chimes and polygonal pioneers.

And the digital storefronts? They’re gateways. Portals to rediscover Suikoden, Alundra, Legend of Dragoon, and a hundred more unsung epics. These titles don’t just live in memory—they’ve found new homes in modern libraries, cherished by old-school devotees and curious newcomers alike.

The PS1’s renaissance isn’t about retro fetishism. It’s about reverence—for a machine that changed everything, and for the people still keeping that charm alive.

Conclusion

By the time the credits rolled on the PS1’s life cycle, it had sold over 100 million units globally. That kind of success doesn’t just happen. It builds momentum, changes expectations, and births dynasties. When the PlayStation 2 arrived, it inherited the throne. Powered by DVD technology, backward compatibility, and an even broader developer base, Sony’s sophomore effort wasn’t just a console—it was a coronation.

Sony tore the old script in half and rewrote it in real-time. The PS1 took chances—on tech, on storytelling, on the players themselves. It courted developers, welcomed the weird, and made room for voices previously shut out by closed platforms and cartridge gatekeeping.

From the grainy FMVs that left us wide-eyed to the tactile snap of a memory card locking into place, every element felt like a glimpse into gaming’s future. The risk of embracing CDs. The audacity of courting teens and adults with shadowy, surreal ads. The brilliance of a controller that evolved mid-lifecycle to meet the needs of a changing medium.

It could’ve flopped. But instead, it redefined the playing field. The PlayStation 1 wasn’t just influential—it was inevitable. It proved that video games could be cinematic, artistic, rebellious, emotional—even a little bit punk rock. And even now, long after its final unit rolled off the line, its echoes still shape the games we play and the way we play them.