In a world dominated by Nintendo’s 8-bit empire, one unlikely machine dared to rewrite the rules. It wasn’t from Sega. It wasn’t from Atari. It came from a surprising alliance between a plucky software company founded by two train-loving brothers and a corporate titan known more for microcomputers than mascots. The PC Engine, later known in the West as the TurboGrafx-16, didn’t just enter the console race—it launched a full-scale rebellion.

Sleek, strange, and blisteringly fast for its size, this pint-sized powerhouse defied expectations. It brought arcade-perfect ports into Japanese living rooms. It introduced CD-ROM gaming before Sony or Sega. And for one incredible moment, it even outsold the Famicom.

How did a company with no arcade pedigree outmaneuver the biggest name in gaming? Why did Japan fall in love with this eccentric underdog? And how did its brilliance get lost in translation overseas? This is the story of silicon ambition, audacious design, and the machine that almost changed everything.

The Steam Locomotive That Started It All

Before it became a name whispered reverently by retro gaming aficionados, Hudson was just two brothers, a shoestring budget, and a dream named after a train. In 1973, Yuji and Hiroshi Kudo weren’t building consoles or shipping games—they were selling telecommunications gear and dabbling in art photography. The kind of company more likely to wire a radio station than electrify an arcade. And yet, out of this eclectic stew of interests and improvisation, something extraordinary began to take shape.

Armed with little more than technical curiosity and an eye for emerging trends, Hudson stumbled into Japan’s exploding computer scene. Not through arcades or silicon giants, but through cassette tapes, magazine listings, and a relentless hunger to invent. The Kudō brothers weren’t chasing Nintendo—they were too busy building something stranger, something smarter.

No one expected a quirky company from Sapporo to disrupt Japan’s gaming hierarchy. But sometimes, revolutions don’t start in boardrooms. They begin with a bee, a blueprint, and a belief that there’s always a better way.

In late ’70s Japan, programming a home computer was a test of patience. Software was often printed line-by-line in magazines, forcing users to manually type it in, debug errors, and pray their BASIC syntax held up. It was tedious. It was time-consuming. It was the Wild West of home computing.

Hudson saw an opportunity—and seized it. Instead of waiting for users to type in code, they sold pre-recorded cassette tapes loaded with software. Just pop in a tape, press play, and watch your microcomputer spring to life. It was elegant, practical, and revolutionary.

These weren’t just programs—they were experiences. Games, utilities, tools that suddenly became accessible to anyone with a tape deck and a dream. Hudson didn’t just make it easier to play—they made it easier to imagine what software could be.

In doing so, Hudson became the first company in Japan to sell a video game for microcomputers. This bold step into uncharted territory didn’t just boost sales—it carved a new lane in Japan’s tech landscape. The bee had found its wings.

Hudson’s Pivot to Console Gaming

The early 1980s in Japan were a golden age for tinkerers. Microcomputers like the NEC PC-8801 and Sharp X1 were finding their way into homes, and a generation of curious minds was teaching itself to code. Hudson thrived in this chaos, releasing a steady stream of games, tools, and experimental software. They weren’t just along for the ride—they were shaping the PC software scene from the inside out.

But then came 1983—and with it, the Famicom.

While most in the industry scoffed at the idea of a new console during the midst of the U.S. video game crash, Hudson saw something different. As soon as they cracked open Nintendo’s new machine, they were floored by its efficiency, its power, and—most importantly—its price. Compared to expensive microcomputers, the Famicom was a miracle of accessible design.

“This is going to be huge,” Yuji Kudo declared, and Hudson bet big on that belief.

They didn’t just develop for the Famicom—they helped shape its DNA. From creating Family BASIC to porting hits like Lode Runner, Hudson didn’t just jump into console gaming—they helped define it. This wasn’t just a pivot; it was a full-speed leap into a future they could help build.

Before Hudson ever dreamed of building a console, they helped define one.

Their first major collaboration with Nintendo was Family Basic—a cartridge bundled with a keyboard and instructional manual that let kids and hobbyists program their own games on the Famicom. It wasn’t flashy, but it was foundational. Family Basic laid the groundwork for a new generation of creators. Masahiro Sakurai, the future mastermind behind Kirby and Super Smash Bros., started his journey with it. Hudson wasn’t just making tools—they were quietly nurturing Japan’s next wave of talent.

Then came Load Runner. Hudson’s port of the classic platform-puzzler turned into a runaway success, cementing their reputation as masterful developers. It was the first third-party game on the Famicom to sell over a million copies, and it opened the floodgates for more ambitious projects.

Titles like Adventure Island and Milon’s Secret Castle brought personality and color to Hudson’s growing catalog, while Bomberman—a simple maze game with explosive mechanics—became a household name. Its addictive multiplayer mayhem would go on to define entire genres and spawn countless sequels.

These weren’t just games—they were building blocks of a legacy. Hudson wasn’t just supporting Nintendo’s rise—they were becoming one of its most essential partners.

The Chip That Changed Everything

By 1987, the Famicom was starting to show its age. For Hudson’s developers—used to pushing the limits of microcomputers and always chasing what’s next—it was getting stale. So, with profits rolling in from their Nintendo hits, Hudson did something bold: they opened their own hardware division. Not to make a console—at least, not yet—but to dream up the next leap forward.

Their engineers set to work designing a chip that would blow the Famicom out of the water. The result? A powerful new architecture capable of smoother animations, larger sprites, and richer color palettes. It was the kind of hardware Hudson’s game designers were aching to develop for—a toolset for the next generation of 2D gaming.

Convinced they were holding lightning in a silicon bottle, Hudson approached Nintendo. What if this chip powered the next Nintendo console? But Nintendo, still riding high on the Famicom’s success and focused on expanding into Europe and enhancing existing cartridges with MMC chips, gave a polite but firm “No thanks.”

That rejection became a turning point. Hudson could’ve shelved the idea. Instead, they doubled down. If Nintendo wouldn’t take the chip, maybe someone else would. Someone with hardware experience. Someone with ambition.

Enter NEC—and a partnership that would rewrite gaming history.

An Unlikely Alliance Is Born

In the early ’80s, NEC wasn’t just another electronics company—they were the king of Japan’s microcomputer market. With over 60% market share and a grip on everything from business systems to home PCs, NEC was riding high. But then came the Famicom.

Nintendo’s little console began eating away at NEC’s dominance, particularly among younger consumers. Suddenly, families weren’t buying PCs for gaming—they were buying consoles. NEC tried to fight back with game-friendly PCs like the PC-8801 mkII SR, complete with bold marketing and even a mascot to match Famitsu’s flair. But software wasn’t enough. The arcade crash had taught everyone a lesson: flashy hardware means nothing without great games.

NEC had the tech, the manufacturing muscle, and the distribution network—but they lacked one critical ingredient: software soul. That’s where Hudson came in.

Here was a top-tier developer with years of PC gaming experience, a killer reputation in the Famicom scene, and a hardware team that had already designed the very chip NEC needed. Hudson wasn’t just a good match—they were the match. NEC knew it. Hudson knew it. And from this unlikely pairing, the seeds of a console revolution were planted.

One was Japan’s microcomputer juggernaut. The other, a scrappy game developer with a bee for a logo and a chip that nobody wanted. On paper, NEC and Hudson Soft couldn’t have been more different. But together, they formed one of the most unexpected—and ambitious—alliances in gaming history.

NEC brought the resources: mass production, component expertise, retail networks. Hudson brought the magic: hardware design, game development chops, and a deep understanding of what players wanted. Their shared vision? A sleek, forward-thinking console that would blow past the Famicom’s limitations and usher in a new era of home gaming.

The result was the PC Engine—a system that married minimalist design with maximum power. No toy-like shapes or chunky red plastic here. Just a clean, compact white console the size of a paperback novel—so small, it set a record as the world’s tiniest game console. But inside? Serious muscle.

This wasn’t a copycat console. It was a statement: gaming could be stylish, sophisticated, and technically dazzling. Aimed at both kids and young adults, the PC Engine didn’t just enter the market—it created a new one. And for the first time in years, Nintendo had a real competitor on its hands.

Inside the Engine

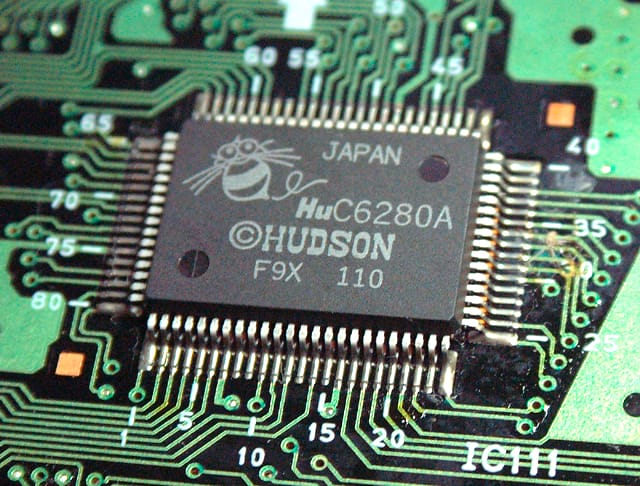

At first glance, the PC Engine might have looked like a sleek, minimalist toy—but under the hood, it was packing serious firepower. Hudson’s in-house chip, the HuC6280, was technically an 8-bit CPU, but don’t let that number fool you. Clocked at 7.16 MHz and capable of 3.3 MIPS, it left the Famicom’s processor in the dust.

But the real star of the show? The graphics architecture. Hudson paired the CPU with two custom-designed 16-bit graphics processors: the HuC6270A VDC and the HuC6260 VCE. This dynamic duo allowed the PC Engine to render up to 482 colors on screen from a palette of 512—unheard of at the time. With support for 64 sprites, smooth scrolling, parallax backgrounds, and hardware-based effects, it brought a level of visual fidelity previously reserved for arcade cabinets.

In a clever stroke, the console’s architecture acted like a hybrid system: 8-bit logic powering 16-bit visuals. It was the best of both worlds—familiar for developers, yet cutting-edge for consumers. From massive boss sprites to richly layered backgrounds, the PC Engine delivered experiences that looked and felt like they belonged in arcades, not living rooms. It was a forward-looking machine that didn’t just keep up with the times—it raced ahead of them.

When Hudson and NEC set out to redefine what a game console could be, they didn’t stop at the hardware—they reimagined the game media too.

Forget bulky plastic cartridges. The HuCard (short for Hudson Card) looked more like a sleek credit card than a traditional game cart. Ultra-thin, lightweight, and easy to store, it gave the PC Engine a futuristic edge. Drawing from Hudson’s earlier B-Card format for Japanese PCs, the HuCard was a natural evolution—one that screamed innovation.

But elegance came at a cost.

While HuCards were more compact and efficient, manufacturing them wasn’t cheap—especially at higher storage capacities. NEC, worried about production costs, initially capped HuCard storage at 2 megabits. That decision clashed with the PC Engine’s 16-bit graphics demands, which needed more

Building a Killer Lineup

Powerful hardware is nothing without the software to show it off—and Hudson knew it. To give the PC Engine a fighting chance against the Famicom, the launch lineup had to be bold, diverse, and technically dazzling.

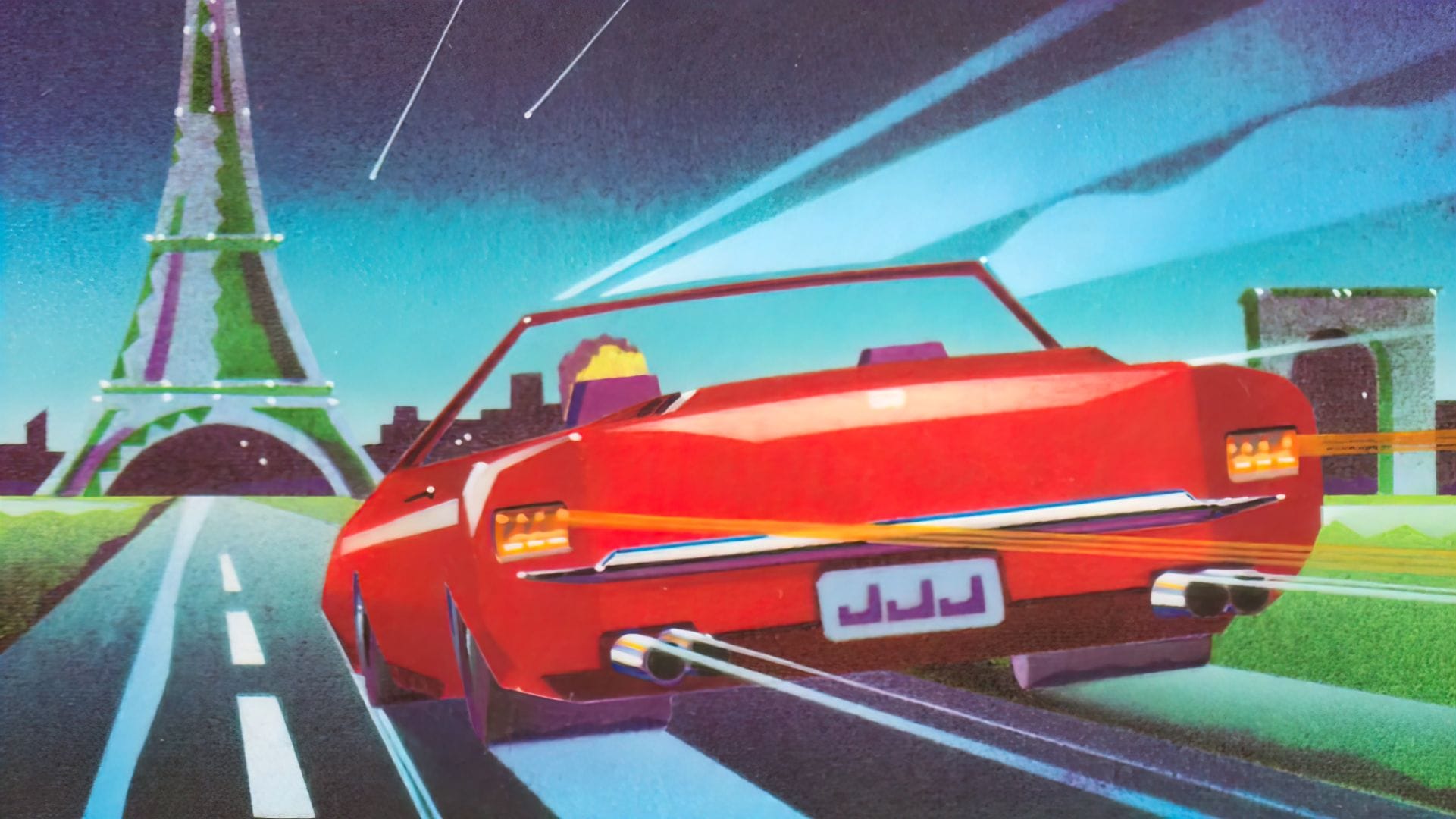

Enter Victory Run—a rally racing game developed in just six weeks. Inspired by the popularity of OutRun and Rad Racer, it showcased the PC Engine’s smooth scrolling and layered backgrounds, giving players a taste of arcade-style driving at home.

Then came Kato & Ken-Chan, based on a beloved Japanese comedy duo. It was loud, goofy, and packed with detailed character animations—including hilariously realistic (and very Japanese) bodily humor. It gave the console a cultural identity and showed that Hudson wasn’t afraid to be weird.

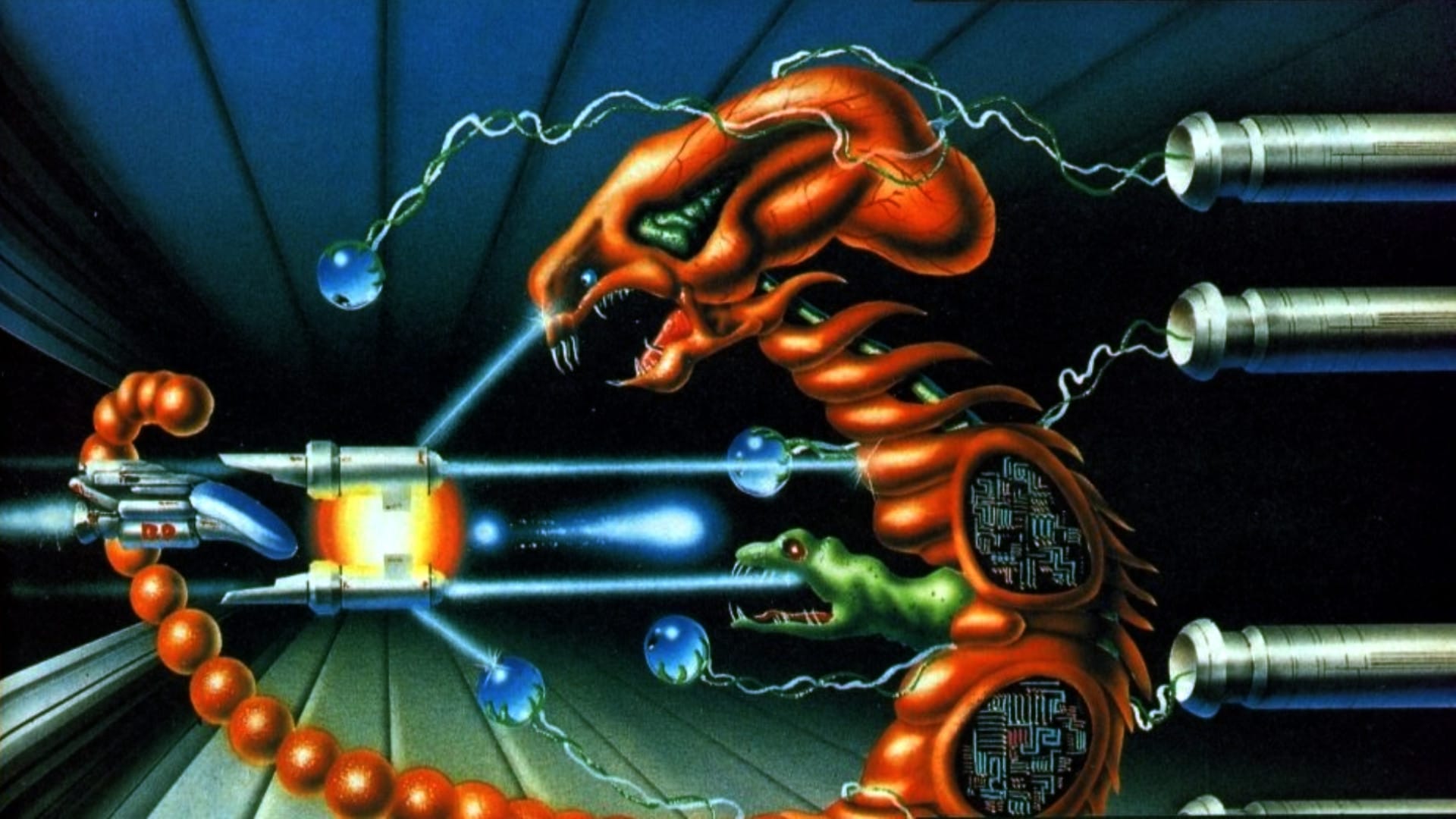

But the real ace in the hole? R-Type.

The arcade hit had just landed in Japanese game centers, and porting it to the PC Engine became Hudson’s obsession. Everyone said it couldn’t be done—not without serious downgrades. But Hudson refused to compromise. When they hit technical limits, they made a radical call: split the game across two separate HuCards. The result? A near-flawless home version that stunned critics and gamers alike.

R-Type wasn’t just a game—it was a statement. It proved the PC Engine wasn’t playing catch-up. It was leading the charge.

A Bold Launch in Japan

On October 30th, 1987, the PC Engine officially hit Japanese store shelves. Priced at 24,800 yen (around $170 at the time), it was notably more expensive than Nintendo’s aging but dominant Famicom, which retailed for 14,800 yen. Skeptics balked at the price. Could a tiny white box from a brand-new alliance really challenge Japan’s console king?

The answer came quickly. Despite its premium tag, the PC Engine sold over 500,000 units in its first week. Gamers were drawn in by the compact design, arcade-perfect visuals, and a game lineup that felt modern and ambitious. The console’s sleek aesthetic and technical prowess made it a must-have, especially among teens and young adults looking for something beyond Mario and Donkey Kong.

Then came the real shocker: in 1988, the PC Engine outsold the Famicom in Japan. It was the first time in years that Nintendo had been dethroned on home turf—a seismic moment in gaming history. Hudson and NEC hadn’t just launched a successful console. They had redefined the playing field.

Just one year after the PC Engine’s launch, Hudson and NEC pulled off another industry first: the world’s first CD-ROM gaming system. In December 1988, the CD-ROM² (officially pronounced “CD-ROM ROM”) add-on hit the market—and it wasn’t just a tech flex. It was a seismic shift in how games could be experienced.

Where cartridges and HuCards capped out at a few megabits, the CD-ROM² offered hundreds of megabytes of storage. That meant bigger games, richer worlds, and—most exciting of all—CD-quality audio. For the first time, home console games featured full voice acting, orchestral soundtracks, and animated cutscenes. This wasn’t just gaming—it was interactive cinema.

Titles like Ys I & II used the format brilliantly, with sweeping music, voiced dialogue, and emotional storytelling that felt lightyears ahead of anything on the Famicom. In just five months, the CD-ROM² sold 60,000 units, kicking off a bold new chapter for console gaming.

While others were still debating whether optical media had a future, Hudson and NEC were already living in it.

The TurboGrafx-16: Lost in Translation

Riding high on the PC Engine’s Japanese success, NEC set its sights on the biggest prize of all: the American market. But somewhere between Tokyo and New York, something got lost in translation.

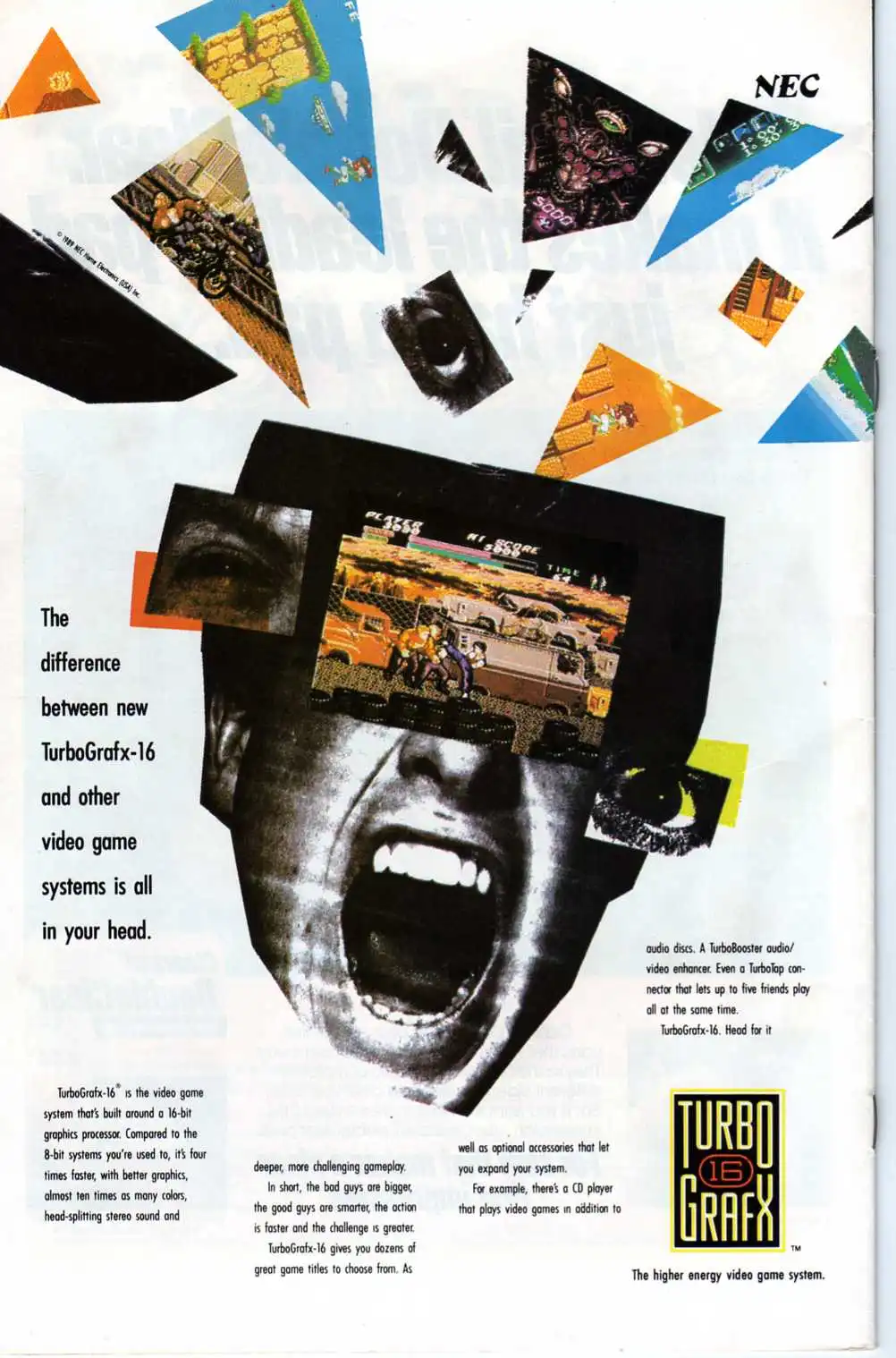

NEC’s U.S. division believed that American consumers wanted bigger, louder, and more futuristic-looking hardware. So out went the sleek, compact PC Engine design. In came the TurboGrafx-16—a chunky, black console that looked more like a VCR than a game system. The rebranding emphasized “16-bit” power, even though the CPU was still technically 8-bit, hoping to dazzle with marketing instead of technical nuance.

Then came the critical misstep: timing. The TurboGrafx-16 launched on August 29, 1989, but only in test markets like New York and Los Angeles. Just two weeks earlier, Sega had unleashed the Genesis, complete with Altered Beast and an aggressive “Genesis Does What Nintendon’t” campaign. Sega’s machine looked sharper, hit shelves faster, and made a louder impact.

Meanwhile, NEC bundled the TurboGrafx-16 with Keith Courage in Alpha Zones, a quirky Japanese platformer that failed to resonate with American gamers. The launch felt underwhelming, and the messaging was muddled.

NEC had the tech. They even had the games. But they didn’t have the moment. And in a market obsessed with first impressions, that made all the difference.

Big Ambitions, Bigger Mistakes

NEC had grand plans for the TurboGrafx-16, but their big swing came with a few glaring missteps—none more damaging than their choice of pack-in title: Keith Courage in Alpha Zones.

Originally based on a Japanese anime (Mashin Hero Wataru), the game was stripped of its cultural context and repackaged for Western audiences with a new name and vague story about a kid who transforms into a mech-warrior. While technically competent, it lacked the wow factor Sega delivered with Altered Beast. Keith Courage just didn’t scream “next-gen.” For many American gamers, it was their first—and last—impression of the TurboGrafx.

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, NEC’s manufacturing team made an even costlier mistake: overproduction. They ramped up production to meet a projected surge in demand that never materialized. By 1991, 750,000 consoles had been built, but far fewer had actually sold. The kicker? Hudson received royalties on every console manufactured, not just the ones that made it into homes.

What was meant to be a bold push into the North American market became a logistical nightmare. NEC wasn’t just losing the console war—they were paying for the privilege.

If the TurboGrafx-16’s U.S. debut was rocky, NEC’s follow-up was even riskier: the TurboGrafx-CD. Launched in August 1990 at a jaw-dropping $399.99, it was the first CD-based console available in North America—an incredible technological leap, but one that came with sticker shock.

Unlike the Japanese launch, the American release came without any pack-in games. Early adopters had to spend even more to get titles like Fighting Street (a rough port of the original Street Fighter) or Ys Book I & II, the latter a beautiful showcase of what CD-ROM gaming could offer—voice acting, orchestral music, and a sweeping fantasy narrative. But it wasn’t enough.

The launch library was sparse. The pricing was brutal. And most players still saw cartridges as the norm.

The TurboGrafx-CD should’ve been a revolution, but instead it became a cautionary tale. While the format had promise, the lack of compelling software and the prohibitive cost kept it from catching fire. It was innovation ahead of its time—without the market ready to follow.

Bonk, Blazing Lazers, and Cult Favorites

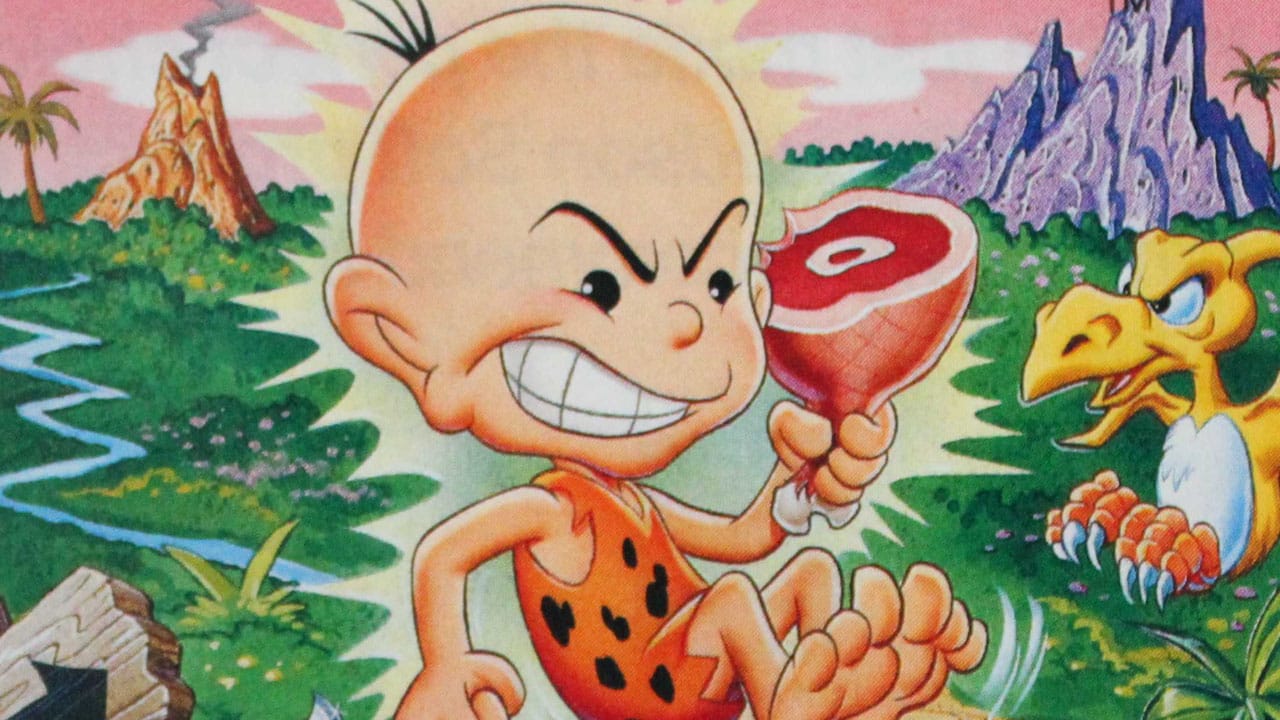

With Mario ruling Nintendo and Sonic sprinting onto the Genesis, NEC needed a face for its console—something bold, quirky, and unmistakably theirs. Enter Bonk, the lovable, big-headed caveman who attacked enemies not with fists or fireballs, but by headbutting everything in sight.

Bonk’s Adventure wasn’t just cute—it was clever. With tight platforming, colorful visuals, and a wacky sense of humor, it gave the TurboGrafx-16 a mascot who could stand proudly alongside its more famous rivals. Bonk quickly became the system’s unofficial spokesperson, starring in multiple sequels and even appearing in print ads and cereal box promotions. For many players, Bonk was the TurboGrafx.

But while Bonk charmed the masses, another genre quietly thrived on the PC Engine: the shmup.

Thanks to the system’s powerful graphics hardware and lightning-fast processors, the PC Engine became a paradise for shoot ’em up fans. Games like Blazing Lazers, Soldier Blade, Air Zonk, and Lords of Thunder didn’t just look great—they played with fluidity and precision that rivaled the arcade.

Even big arcade developers like Konami, Namco, and Taito saw the potential, bringing over premium ports that often outshined the competition’s versions. The console’s HuCard format made fast-paced action easy to load and play, while CD-ROM titles pushed soundtracks and effects to new heights.

Whether you came for the caveman or stayed for the bullets, the PC Engine had something for you—and shmup fans found their forever home.

TurboExpress and the Portable Power Fantasy

In 1990, NEC dropped jaws with the TurboExpress, a handheld powerhouse that promised to bring full console-quality gaming to your fingertips. Unlike the Game Boy or Game Gear, the TurboExpress didn’t use scaled-down ports or simplified versions—it played actual TurboGrafx-16 HuCards, meaning no compromises, no downgraded visuals, and no alternate libraries.

With a 2.6-inch backlit LCD screen, stereo sound, and rich colors, it was a technical marvel—essentially a TurboGrafx you could fit in a (very large) coat pocket. Gamers could even connect two TurboExpress units with a link cable for multiplayer action, or pop in a TV tuner adapter to watch live broadcasts right on the go.

But for all its flash, the TurboExpress came with serious flaws. Priced at $249.99, it was nearly double the cost of a Game Boy. Worse still, it devoured six AA batteries in just three hours—less “on the go” and more “stay near an outlet.” The screen, while impressive, was prone to dead pixels and ghosting.

It was a glimpse into the portable gaming future—but the tech just wasn’t quite there yet. Still, NEC’s ambition was clear: push boundaries, break norms, and keep innovating, no matter the cost.

The PC Engine LT and Other Oddities

By 1991, NEC was deep into its experimental phase—pushing the PC Engine into forms no other console dared to take. Case in point: the PC Engine LT, a bizarre and beautiful fusion of luxury tech and gaming gadgetry.

Shaped like a mini laptop, the LT featured a built-in 4-inch screen, stereo speakers, and a foldable clamshell design. It could play HuCards out of the box and connect to the CD-ROM² add-on with an extra adapter. It was sleek, futuristic, and portable—at least in theory. The catch? It launched at an eye-watering 99,800 yen (about $770 USD at the time). That made it more of a collector’s trophy than a mainstream product.

And the LT wasn’t alone. NEC also released wild variants like the SuperGrafx (a more powerful but short-lived successor) and the CoreGrafx line (slimmer revisions of the original hardware), each offering small tweaks or upgrades that appealed mostly to hardcore fans.

These systems proved one thing above all else: NEC wasn’t afraid to take risks. Even as market share wavered and competitors solidified their footholds, NEC and Hudson kept innovating, iterating, and imagining what gaming could be—even if most people weren’t buying it.

TTi and the Turbo Duo: A Last-Ditch Effort

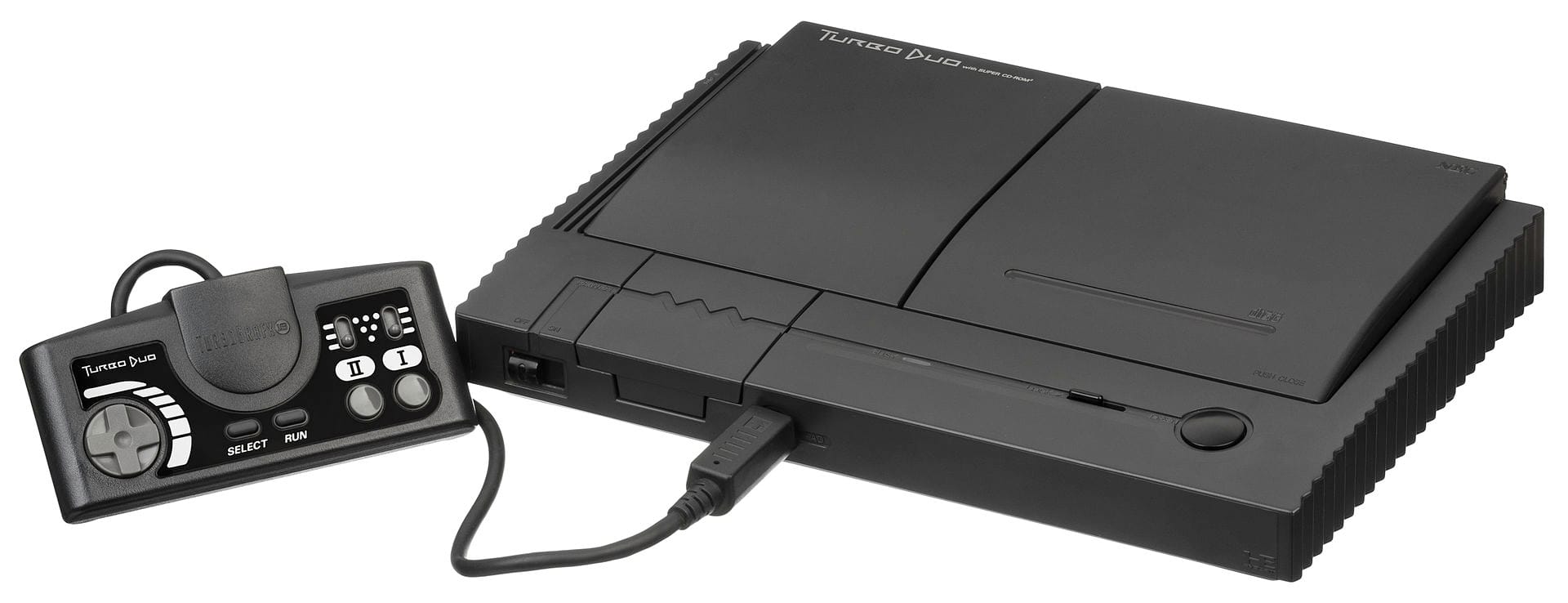

By 1992, NEC and Hudson knew the TurboGrafx brand was fading fast in North America. To reboot their fortunes, they formed a new joint venture—Turbo Technologies Inc. (TTi)—and unleashed their ultimate weapon: the Turbo Duo.

This sleek, all-in-one system merged the TurboGrafx-16 and its CD-ROM add-on into a single unit. With built-in Super System Card support, it could play HuCards, CD-ROM², and Super CD-ROM² games right out of the box. No adapters, no upgrades—just streamlined access to the platform’s most advanced software. It launched at $299.99, bundled with five games including Ys Book I & II, Bonk’s Adventure, and Gate of Thunder, making it a great value on paper.

But TTi didn’t just rely on hardware—they went all-in on marketing. Enter Johnny Turbo, a snarky, leather-jacketed comic book character who waged a strange and aggressive ad campaign against Sega. He mocked the Sega CD as overpriced and underpowered, and cast the Turbo Duo as the cooler, more capable alternative.

While memorable, the campaign missed its mark. The tone came off as bitter rather than bold, and Sega fans weren’t swayed. Worse, third-party support remained thin, and most retailers had already given their shelf space to Sega and Nintendo.

The Turbo Duo was a technical marvel—compact, capable, and forward-thinking—but it arrived too late, with too little software, and a message that felt more desperate than disruptive.

A Tale of Two Markets

On paper, the TurboGrafx-16 and PC Engine were the same system. But in practice, they lived very different lives on opposite sides of the Pacific.

In Japan, the PC Engine became a cultural phenomenon, with over 650 games released across HuCard and CD-ROM formats. From shmups and RPGs to dating sims and mahjong games, the library was vast, diverse, and distinctly Japanese. Developers like Falcom, Taito, Namco, and Konami all supported the platform enthusiastically, drawn in by its technical capabilities and thriving user base.

Meanwhile, North America saw just under 140 officially released titles. The TurboGrafx-16 was always fighting an uphill battle—squeezed between Sega’s cool factor and Nintendo’s market dominance. That, combined with NEC’s missteps in marketing and distribution, left third-party publishers reluctant to jump in. The limited install base didn’t justify expensive localizations, especially for CD-ROM games.

To make matters worse, Nintendo’s aggressive licensing practices during the NES era discouraged companies from developing for rival platforms. By the time those restrictions were challenged in court, the damage had already been done—the TurboGrafx was too far behind.

What emerged was a frustrating paradox: a console celebrated in Japan as a genre-defining powerhouse, but remembered in the West as a niche curiosity with flashes of brilliance.

The Final Years: An Engine That Kept Running

Even as the mainstream spotlight shifted to the Super Nintendo and Sega Genesis—and soon after, the PlayStation and Saturn—the PC Engine refused to fade quietly. In Japan, it evolved.

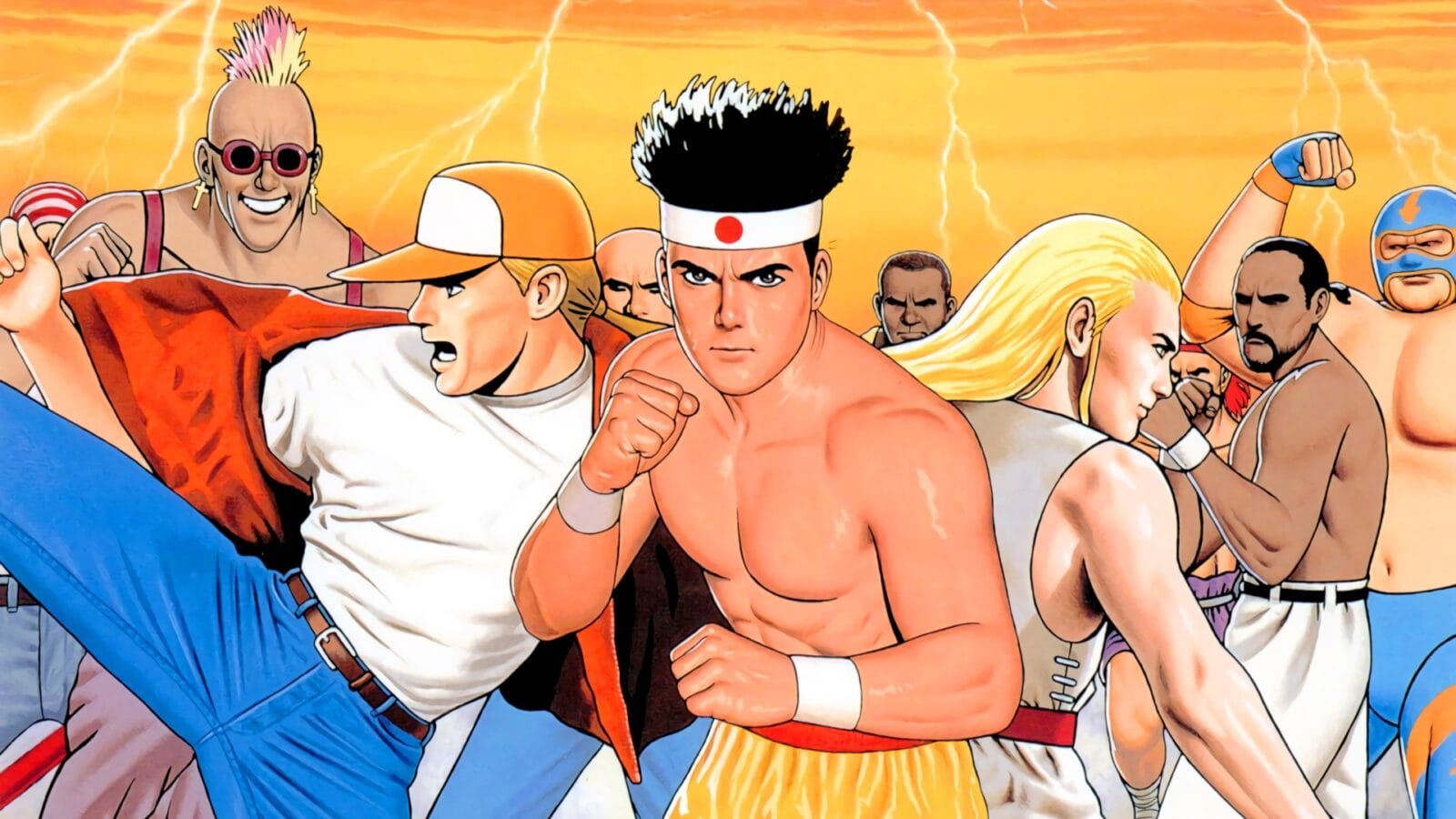

In 1994, NEC released the Arcade Card, a memory expansion that supercharged the PC Engine’s capabilities. With 2MB of additional RAM, it allowed the console to run visually stunning ports of Neo Geo arcade hits like Fatal Fury 2, Art of Fighting, and World Heroes 2. While these ports weren’t perfect, they were astonishing achievements on such dated hardware.

In North America, however, the story was different. The Arcade Card never made it across the Pacific, and NEC had already begun winding down official support. In May 1994, Turbo Technologies Inc. announced the end of Turbo Duo production—but that wasn’t the end of the road.

A new company, Turbo Zone Direct, stepped in to keep the flame alive. They offered repair services, sold remaining stock, and continued distributing games and accessories via mail order all the way through 2001. Meanwhile, dedicated fans kept trading import titles, modding systems, and sharing the best of the Japanese library with the rest of the world.

In Japan, the PC Engine outlived its rivals in sheer software longevity, with new games still being released as late as 1999. Its library continued to grow, its legacy deepened, and its cult following cemented.

Even without global dominance, the PC Engine had done the unthinkable: it challenged Nintendo, pioneered CD gaming, and inspired generations of developers. It didn’t just run—it roared, quietly, for over a decade.

Legacy of the PC-Engine

The PC Engine may not have conquered the global market, but its impact on gaming is undeniable. It was a cult classic with a revolutionary heart—a console born from a wild partnership between a computer titan and a game studio with no hardware pedigree, that somehow managed to challenge Nintendo at the height of its power.

It pioneered CD-ROM gaming years before Sony or Sega would make it mainstream, delivering lush soundtracks, voice acting, and full-motion cutscenes that redefined what console games could be. It pushed the limits of visual fidelity with hardware that felt lightyears ahead of its time, giving players arcade-quality experiences in their living rooms.

And it created a platform that became a haven for genre specialists—especially for shoot ‘em ups, which flourished in a way rarely seen on home consoles.

For developers, the PC Engine proved that bold ideas and smart engineering could open new creative doors. For players, it offered a quirky, powerful, and deeply lovable alternative to the mainstream. And for the gaming world at large, it quietly laid the groundwork for the future of multimedia gaming.

Today, the PC Engine lives on—not just in collectors’ hearts, but in the DNA of the consoles that followed it. It was never the biggest, but it was often the first, and sometimes, that’s what matters most.