In the early ‘90s, stepping into an arcade felt like entering a global coliseum. The air buzzed with the clack of joysticks, the roar of digitized crowds, and the unforgettable cries of “Hadouken!” Capcom’s Street Fighter II had detonated like a pop-culture megaton when it landed in arcades in March 1991, and almost overnight, it changed everything. No longer were fighting games niche distractions—SFII turned them into a cultural movement.

With its colorful roster of world warriors, tight controls, and combo-heavy gameplay, Street Fighter II became the gold standard—and naturally, imitators rushed to cash in. Suddenly, the market was flooded with martial arts tournaments from all corners of the globe. Fatal Fury, Art of Fighting, World Heroes, and countless others joined the fray, each trying to land their own knockout blow.

Then came Data East’s Fighter’s History in 1993. To many, it felt like a game you’d swear you’d already played—one where the names were different, but the bones were all too familiar. Was it a tribute? A shameless clone? Or something more complicated? Fighter’s History may not have set the arcade world on fire, but it did land squarely in the crosshairs of Capcom’s legal team—and that’s where its story really gets interesting.

A World Obsessed with World Warriors

Before 1991, fighting games were mostly simple affairs—Karate Champ, Yie Ar Kung-Fu, Street Fighter (the first one). They had their fans, but they were more curiosity than cornerstone. Then Street Fighter II: The World Warrior showed up and flipped the script. It didn’t just improve on the formula—it practically invented the modern fighting game genre.

Capcom’s magnum opus brought together something revolutionary: a diverse, global cast of fighters, each with unique moves, fighting styles, and backgrounds. Players could choose from a sumo wrestler, a green-skinned beastman, a U.S. Air Force colonel, and a Chinese kung-fu prodigy. This international lineup gave SFII mass appeal, allowing players to connect with characters from different parts of the world, and it gave the game a globetrotting flair that felt like a digital martial arts movie.

Just as importantly, Street Fighter II introduced mechanics that would become industry standards: special moves with directional inputs, combos (initially an accident that became a feature), and tactical depth beyond button-mashing. Its influence was immediate and seismic—arcades filled with challengers, home ports flew off the shelves, and game developers everywhere took notes.

Suddenly, every new fighting game needed a multicultural cast, elaborate backstories, and signature special moves. It wasn’t enough to just let players throw punches—you had to give them fireballs, flying kicks, and stage-specific flavor. The era of the “world warrior” had begun, and the arcade was its battlefield. In this frenzy of flying fists and flashing projectiles, Fighter’s History entered the ring—ready or not.

Data East Steps Into the Ring

By 1993, the arcade was a crowded dojo. Nearly every major publisher had thrown their gi into the ring, hoping to capture even a sliver of the fighting game gold rush kicked off by Street Fighter II. Enter Data East, a company better known for oddball hits like BurgerTime, Karnov, and Bad Dudes, but no stranger to the arcade floor. With Fighter’s History, they weren’t just making a fighting game—they were making a statement.

At first glance, Fighter’s History looked like a textbook case of “if it ain’t broke, copy it.” The game featured a cast of international warriors, colorful stage backdrops, and familiar six-button controls. But behind the scenes, Data East had a more earnest goal: to build a fighting game that could hang with the best of them, not just mimic them. This was their shot at serious arcade credibility.

The development team, led by seasoned arcade veterans, infused Fighter’s History with a mix of classic fighting mechanics and experimental twists. They borrowed liberally from what worked—especially from Capcom and SNK—but also tried to add new wrinkles, like the unique weak-point system that rewarded precision over brute force.

Still, the game was undeniably launching in the long shadow of giants. By 1993, Street Fighter II had seen multiple updates, and Fatal Fury was evolving. Fighter’s History didn’t arrive with the same fanfare, but it did arrive with something else: controversy. And whether they intended it or not, Data East had just punched their way into one of gaming’s most infamous legal battles.

Fighter’s History vs. Street Fighter II: Spot the Differences

On the surface, Fighter’s History looks like it was forged in the same dojo as Street Fighter II—and maybe even stole a few of its gi. The visual similarities were hard to ignore, prompting fans and lawyers alike to ask: was this a tribute, a knock-off, or something in between?

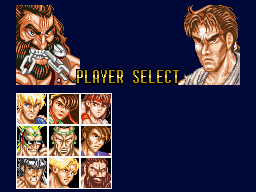

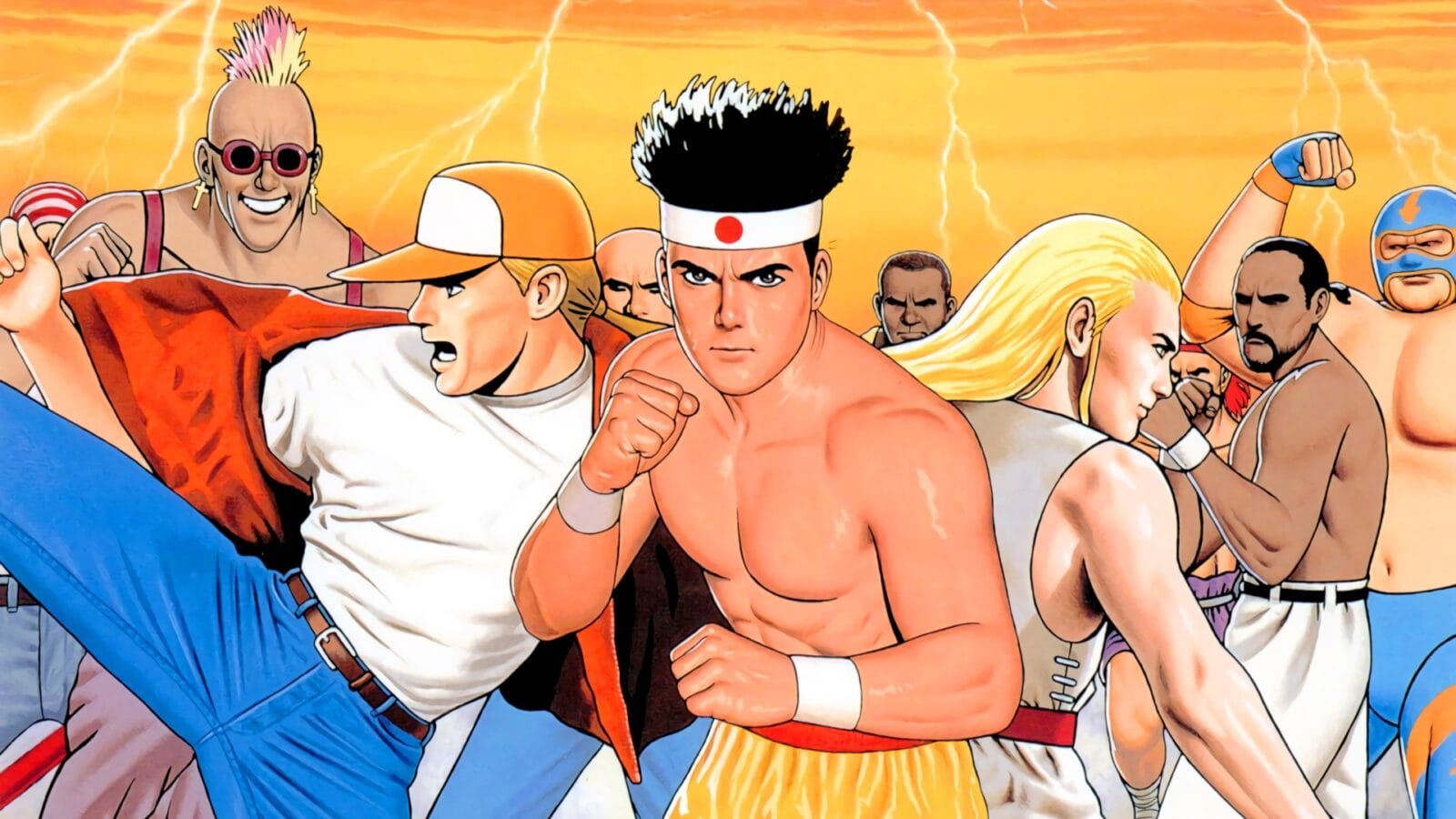

Let’s start with the fighters themselves. Fighter’s History boasts a familiar format: eight playable characters from around the world, plus bosses. But many players couldn’t help but notice how closely some of these newcomers resembled Capcom’s icons. Ray, the blond, all-American brawler with a red headband and projectile punch? Not unlike a certain “Ryu with a mullet.” Feilin, a Chinese martial artist in traditional garb, echoes Chun-Li’s aesthetics and stance just a bit too closely. And then there’s Lee, a stoic kung-fu master with a rapid-fire attack—ringing even more alarm bells

Even the postures, win poses, and animations had that Street Fighter II DNA. While some characters brought more original flair—like the bizarre, flame-spewing Karnov—others felt like thinly veiled reinterpretations, if not outright duplicates.

Beyond their visual similarities, the Fighter’s History roster aimed to deliver the same international flair as SFII. From Ryoko, a judo champ inspired by real-life Olympian Ryoko Tamura, to Jean, a suave French kickboxer, the cast followed familiar fighting game archetypes to a tee. But the most notable name? Karnov—a former Data East boss character turned final boss here. His presence added a meta twist, placing an already-established character in a new setting to anchor the game and its universe

Still, many of the character abilities and personalities mirrored the Street Fighter cast a little too well, and the comparisons weren’t lost on players—or Capcom.

The echoes didn’t stop with the fighters. Stage backgrounds featured exotic, globe-spanning locales: marketplaces, temples, industrial zones—each one distinctly reminiscent of Street Fighter II’s world tour. Even the placement of spectators, objects, and destructible elements felt oddly familiar. It wasn’t just the themes; it was the framing, the color palettes, even the atmospheric sounds.

Sure, fighting games tend to borrow from similar cultural and visual motifs—but Fighter’s History often looked like it had flipped through Street Fighter II’s design doc and changed just enough to pass as new. And that’s precisely what would land Data East in hot water not long after.

Unique Mechanics or Just Tweaks?

While Fighter’s History drew plenty of heat for its visual and structural similarities to Street Fighter II, it wasn’t completely devoid of originality. Beneath the familiar six-button surface and international roster, Data East slipped in one notable twist—a mechanic that set it apart from the sea of imitators.

At the heart of Fighter’s History’s gameplay innovation was the “weak point” system. Each character had a specific piece of clothing or gear that, when repeatedly struck, would flash and eventually trigger a stun state. Think of it like a glowing bullseye—land enough hits in the right spot, and you’d earn a brief window to punish your opponent freely.

It was a clever risk-reward wrinkle: target the weak point, and you might land a free combo. Ignore it, and you play a more traditional footsies game. It added a layer of strategy not seen in Capcom’s offering, where stun was more nebulous and not tied to any visual indicator. It also gave defensive-minded players something to protect, subtly altering how matches flowed.

Visually, the weak point system was striking. A fighter’s scarf, helmet, or shoulder pads would start to glow mid-match, telegraphing vulnerability. It created tension—do you go for the weak point and risk whiffing, or do you play it safe and chip away the old-fashioned way?

This system encouraged players to not just focus on general zoning or combo execution, but on specific targeting. It was part gimmick, sure—but it gave Fighter’s History its own identity, however small. And for those who mastered the timing and spacing, the payoff could be huge.

Mechanically, both games felt remarkably similar at first blush. Special moves were executed with familiar quarter-circle or charge inputs, and characters had a healthy mix of projectiles, anti-airs, and dashing strikes. If you could throw a Hadouken, you could throw a Fireball Burst in Fighter’s History with barely a second of adjustment.

That said, Fighter’s History was often regarded as slightly more floaty and inconsistent, especially when it came to hit detection. Some moves had questionable priority, and spacing could feel slippery compared to Street Fighter II’s razor-sharp precision. But for all its rough edges, Fighter’s History still managed to feel like a fully playable—if less polished—alternative to the genre leaders.

In the end, the weak point system stood as the game’s one major innovation. It wasn’t enough to silence the clone accusations, but it did hint that Data East wasn’t just trying to copy—they were trying to compete.

The Fatal Fury and Art of Fighting Factor

Fighter’s History may have drawn the most comparisons to Street Fighter II, but Capcom wasn’t the only giant looming over the arcade scene in the early ‘90s. SNK, with its fast-growing lineup of competitive fighters like Fatal Fury and Art of Fighting, was setting its own standards—and Fighter’s History quietly borrowed just as much from them as it did from Capcom.

While Capcom may have sparked the fighting game boom, Data East had a broader playbook in mind. Dig beneath the surface of Fighter’s History, and you’ll find just as many SNK-style elements as Capcom influences. This wasn’t a one-to-one knockoff—it was more like a Frankenstein’s monster, stitched together from the best (and most marketable) parts of multiple hits.

The tone, the structure, even some of the character archetypes felt more in line with SNK’s brand of gritty, grounded martial arts stories than Capcom’s flashier anime-infused stylings. And for arcade veterans, the fingerprints of Fatal Fury and Art of Fighting were hard to miss.

SNK’s influence showed up in several mechanical and aesthetic choices. Art of Fighting had introduced dynamic zooming effects, where the camera pulled in and out depending on the distance between fighters. Fighter’s History didn’t go quite that far, but it featured a similar dramatic flair in its animations and screen shake, lending weight to heavy strikes.

Likewise, the charge input system—where players had to hold directions for special moves—was common in SNK fighters, and it found a comfortable home here too. Characters like Jean and Ryoko had moves that clearly borrowed from this style, giving them a more methodical, timing-based feel.

There was also a subtle SNK-style grit in the presentation: more martial arts realism, less cartoonish exaggeration. The characters weren’t just world warriors—they were bruisers, judokas, and Muay Thai fighters who looked like they’d trained in dusty dojos rather than neon-lit arenas.

Fighter’s History wasn’t uniquely guilty of imitation—it was typical of the era. The market demanded recognizable patterns, and games that diverged too far from the Street Fighter formula often flopped. So Data East, like many others, tried to thread the needle: offer just enough difference to stand out, while staying familiar enough to draw in quarters.

Capcom Strikes Back: The Lawsuit That Shook the Arcade Scene

By the time Fighter’s History hit arcades in 1993, Capcom had seen enough. While clone fighters were nothing new, Data East’s effort crossed what Capcom believed was a legal line—and they weren’t about to let it slide. That same year, the Japanese gaming giant filed a lawsuit against Data East, accusing them of copyright infringement and demanding the game be pulled from circulation.

Capcom’s case wasn’t just about bruised egos or competitive anxiety—it was about protecting what had quickly become one of gaming’s most valuable franchises. With Street Fighter II dominating both arcades and home consoles, Capcom argued that Fighter’s History was far more than just “inspired by” their work. To their legal team, it was a copycat in designer’s clothing.

The lawsuit was filed in the U.S. District Court in California, kicking off what would become one of the most significant legal battles in video game history up to that point. It wasn’t just a fight between two companies—it was a question of where homage ends and theft begins.

Capcom’s claim zeroed in on the similarities: not just in the gameplay structure, but in character archetypes, move sets, visual presentation, and stage designs. They argued that Fighter’s History lifted substantial, distinctive elements from Street Fighter II—to the point where the core “feel” of the game was virtually indistinguishable.

This wasn’t just about blond karate dudes and sonic booms. It was about whether the expression of a genre—its characters, aesthetics, and systems—could be protected under copyright law. And it raised a major question for the entire industry: how close is too close when you’re working within a defined genre?

Capcom didn’t come in lightly. They weren’t just asking for an arcade recall—they were demanding 623 million yen in damages, a sum that represented both the commercial impact and the perceived dilution of their iconic brand. If the court had ruled in their favor, Fighter’s History could have been wiped off the arcade map, setting a precedent that might’ve stifled dozens of other fighters riding the same wave.

But Data East wasn’t backing down. Armed with internal design documents, developer interviews, and a VHS tape showcasing how their characters and systems diverged from Capcom’s, they prepared to go the distance. The outcome would shape how developers approached fighting game design for years to come—and whether Capcom could claim ownership of an entire style of play.

It wasn’t just another case on the docket—it was the first major legal showdown over fighting game mechanics, character design, and what could (or couldn’t) be copyrighted in a rapidly evolving medium. In 1994, the case of Capcom U.S.A., Inc. v. Data East Corp. became a landmark moment, not just for the two companies involved, but for the entire gaming industry. And presiding over it all was Judge William H. Orrick Jr., tasked with navigating a lawsuit that was more joystick than jurisprudence.

Judge Orrick, a U.S. District Court judge in Northern California, suddenly found himself at the center of an industry-defining debate. Could Capcom claim ownership over certain gameplay elements that had become genre staples? Was Data East’s Fighter’s History just a copy of Street Fighter II, or a distinct enough product to stand on its own? These were the questions Judge Orrick had to answer—without the benefit of decades of precedent in video game law.

His decision would set a tone for how copyright law applies to interactive media—and by extension, how much creative “borrowing” was fair game in game development.

Capcom’s Argument vs. Data East’s Defense

Capcom came out swinging. Their case hinged on the idea that Fighter’s History didn’t just resemble Street Fighter II—it replicated it in feel, function, and form. From Ray’s red headband and fireball move to Feilin’s high-kicking resemblance to Chun-Li, Capcom alleged that Data East had crossed the line from inspiration into outright duplication.

Data East’s rebuttal was sharp: fighting games, by their nature, follow shared conventions. Just like platformers involve jumping and shooters involve aiming, one-on-one fighters use similar visual languages and control schemes. And crucially, many of the concepts Capcom claimed were stolen were not protectable by copyright, being considered “scènes à faire”—generic elements required by the genre.

A crucial part of Data East’s defense came in the form of a VHS tape—a behind-the-scenes look at the development of Fighter’s History, including early concepts and comparisons between characters and mechanics. It wasn’t just PR fluff. The tape showed that Data East had deliberately tried to differentiate their fighters, even if the end result looked familiar.

The footage also highlighted Fighter’s History’s weak point system, a mechanic that had no direct analog in Street Fighter II, as well as animations and inputs that, while similar in function, were distinct in execution. The message was clear: this wasn’t a copy-paste job—it was an attempt to iterate within a shared design language.

The Verdict & Aftermath

In the end, Judge Orrick agreed. He ruled in Data East’s favor, concluding that the elements Capcom took issue with weren’t protected by copyright. The case was closed—but the conversation around originality in game design had only just begun.

When the gavel finally fell in 1994, it wasn’t just a win for Data East—it was a watershed ruling for the entire video game industry. After months of back-and-forth, expert testimonies, and side-by-side gameplay footage, Judge William H. Orrick Jr. ruled in favor of Data East, allowing Fighter’s History to remain in arcades and marking the end of Capcom’s legal challenge.

Judge Orrick’s ruling essentially stated that while Fighter’s History did indeed bear a resemblance to Street Fighter II, it didn’t cross the legal threshold for copyright infringement. The court acknowledged similarities in structure and presentation but found that the game was not “substantially similar” in a way that violated the law.

It was a sigh of relief for Data East—and a subtle jab at Capcom’s attempt to gatekeep the genre it had helped popularize. Fighter’s History was free to remain in arcades, and Data East avoided the steep financial penalty Capcom had demanded.

One of the core takeaways from the case was this: you can’t copyright game mechanics. The ruling clarified that gameplay ideas—like six-button layouts, special move inputs, and character archetypes—are considered systems or functional elements, and thus fall outside the scope of copyright protection.

This was huge. If Capcom had won, it might’ve opened the door to companies copyrighting control schemes or character roles, potentially locking out competitors from creating within the same genre. The court’s decision ensured that while art assets and code could be protected, the feel of a game remained part of a shared creative commons.

Unfortunately, Fighter’s History didn’t mark a new golden age for Data East. The company struggled through the late ‘90s and eventually declared bankruptcy in 2003. Its properties were scattered, with many—including Fighter’s History—being picked up by G-Mode, a Japanese mobile content company that has since become the unlikely caretaker of Data East’s legacy.

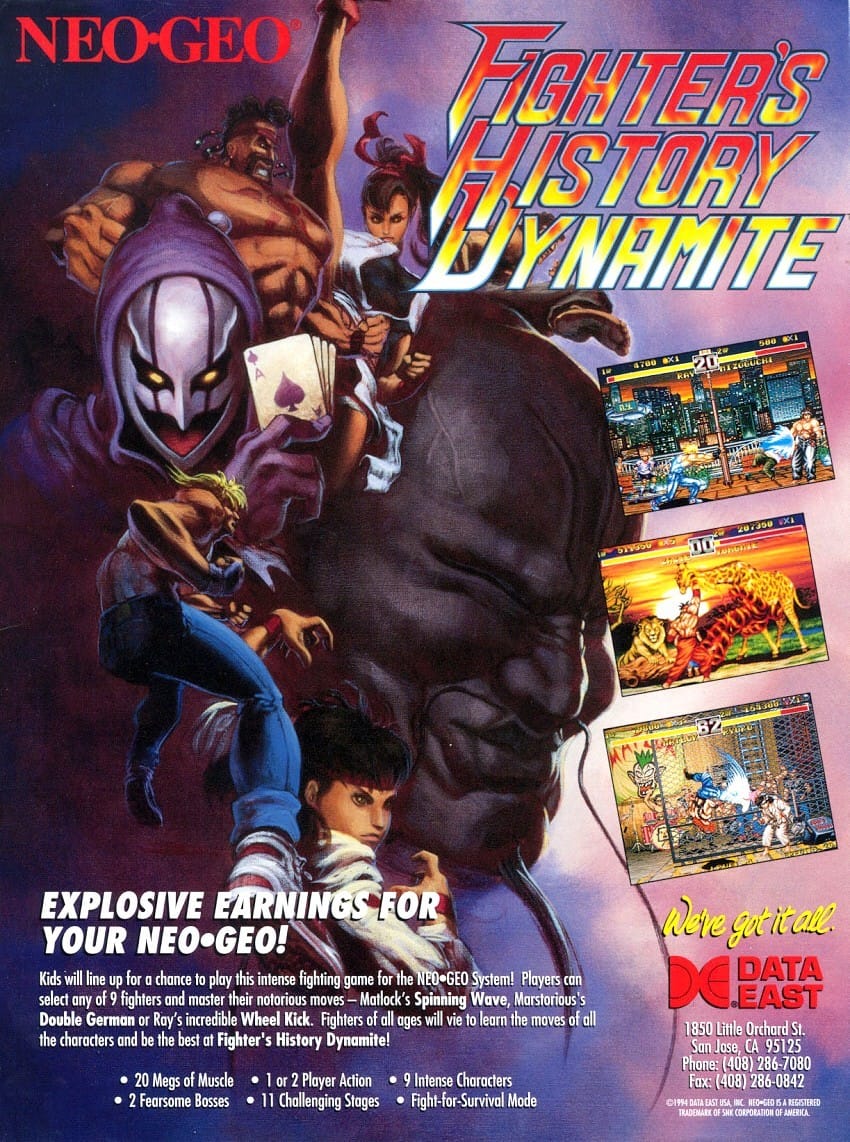

While G-Mode has done little with the series beyond re-releases, the rights being preserved has allowed Fighter’s History Dynamite to resurface on platforms like Nintendo Switch, PS4, and Xbox via HAMSTER’s ACA NeoGeo series. Though there’s no sign of a reboot or remake, the game’s continued availability speaks to its odd staying power—more than just a footnote, it’s a cult classic that refuses to vanish completely.

For Capcom, the loss didn’t slow Street Fighter’s dominance. But for smaller developers, it was a signal: you could stand toe-to-toe with giants, legally and creatively, as long as you brought something slightly new to the table.

Legacy and Sequels

While Fighter’s History never reached the fame of its rivals, it refused to go quietly. Over the years, it spawned a sequel, appeared in some surprising places, and built just enough of a legacy to keep retro fans curious. Its name might not light up the arcade marquee like Street Fighter or King of Fighters, but Fighter’s History never truly disappeared—it just ducked into the shadows of niche gaming history, waiting to be rediscovered.

Released in 1994 for Neo Geo arcades, the follow-up Fighter’s History Dynamite (renamed Karnov’s Revenge in the West) polished up the original formula without reinventing it. The entire cast returned, now joined by newcomers like Yungmie, a Korean taekwondo expert, and Zazie, a Kenyan martial artist. Mechanics were tightened, visuals got a bump, and Karnov became fully playable—finally putting the big man front and center.

Though it never quite broke out of cult status, Dynamite is widely regarded as the better game, and still gets play in retro tournaments and mystery game side events. Thanks to the Neo Geo’s solid hardware, it holds up surprisingly well, with a faster pace and more dynamic matches than its predecessor.

The original Fighter’s History was ported to the Super Nintendo in 1994 with decent results. While scaled down from the arcade, the SNES version retained the six-button layout and even included all fighters—rare for the time. That version became many players’ first exposure to the game and continues to enjoy a nostalgic fanbase.

As for Fighter’s History Dynamite, it found a second life on the Sega Saturn in Japan as part of the Data East Arcade Classics lineup—though that release remains relatively obscure and pricey. More recently, the game has popped up on retro compilations and digital storefronts, such as the ACA NeoGeo line on modern consoles, giving a new generation a taste of Karnov’s fury.

Clone or Competitor? Re-Evaluating Fighter’s History

More than 30 years later, Fighter’s History still sparks debate: was it a shameless clone, or a misunderstood underdog? The arcade era was filled with games trying to surf the Street Fighter II tidal wave, but some—like Fighter’s History—got caught in its undertow. Looking back now, with the benefit of hindsight and a broader understanding of the fighting genre, it’s time to ask if the “rip-off” label really holds up.

There’s no denying the surface-level similarities. Ray’s red headband and fireball scream “Ken/Ryu,” Feilin’s rapid kicks echo Chun-Li, and the six-button layout is straight out of Capcom’s playbook. But to call it a rip-off is to flatten the nuances that Fighter’s History actually brought to the table.

The animations, while familiar, had their own flavor. The roster, though clearly built on archetypes, also included offbeat choices like Ryoko (a judo prodigy) and Clown (a twisted carnival brawler) that gave the game a unique tone. It wasn’t revolutionary—but it was far from lazy.

Back in the early ‘90s, almost every fighting game borrowed from Street Fighter II—because it worked. What Fighter’s History did, arguably more than some of its peers, was try to refine rather than reinvent. It didn’t break genre conventions; it leaned into them. The line between inspiration and imitation is fuzzy, but Fighter’s History sits somewhere in the middle—not a trailblazer, but not an empty shell either.

That’s where context matters. Games like Eternal Champions, World Heroes, and Power Instinct also rode the genre wave, each with their own spin. Compared to those, Fighter’s History may have played it safer—but it still stood its ground.

In the unofficial second tier of ‘90s fighting games, Fighter’s History carved out a quiet legacy. World Heroes had the time-travel gimmick. Power Instinct brought bizarre humor and an aging grandma who could transform into her younger self mid-fight. Fighter’s History? It had tight, responsive controls and a distinct emphasis on grounded fundamentals.

If there’s one character who’s outshone the game itself, it’s Karnov. Originally the fire-spewing star of his own platformer in 1987, Karnov was reborn as the final boss of Fighter’s History—shirtless, rotund, and unreasonably powerful. His presence alone added instant flavor to the game and helped tie it into Data East’s broader universe.

Karnov became such a fan favorite that he returned as a playable character in Karnov’s Revenge (aka Fighter’s History Dynamite), and to this day, he remains a kind of unofficial mascot for the series. Within certain corners of the internet, “Karnov is love, Karnov is life” isn’t said entirely in jest.

For the fans who stuck around—and the new players who stumble onto it via emulation or fightcade—Fighter’s History lives on not just as a knockoff, but as a curious, charming, and weirdly compelling relic from fighting games’ most chaotic era.

It was never going to dethrone Street Fighter, Fatal Fury, and later, King of Fighters. But it holds up better than many would expect. The SNES port gained a modest cult following, and its 1995 sequel Karnov’s Revenge is still respected by hardcore fans who appreciate its stripped-down, back-to-basics design.

A Cult Following Emerges

Despite its rocky critical reception and constant comparisons to Street Fighter II, Fighter’s History didn’t fade into total obscurity. In fact, over the decades, it’s gained something arguably more meaningful than mass-market success: a passionate, weirdly loyal cult following. From retro arcade enthusiasts to meme-loving fighting game communities, this so-called “clone” has carved out a peculiar but enduring legacy.

Ask fans why they keep coming back to Fighter’s History, and you’ll hear about more than just nostalgia. The game’s tight inputs, snappy pacing, and grounded fundamentals make it surprisingly enjoyable once you move past the superficial similarities to Capcom’s juggernaut. For players who like stripped-down, no-frills fighting systems, Fighter’s History offers a refreshing throwback to the basics.

Then there’s the charm. Whether it’s the absurd voice samples, the awkward animations, or the slightly off-kilter character lineup, Fighter’s History has a personality all its own—quirky, janky, but oddly lovable.

Though Fighter’s History never became an EVO headliner, it’s popped up in side tournaments and mystery game brackets over the years, usually to great amusement. The glowing weak point system can lead to some hilarious upsets, with players yelling “HIT THE HEADBAND!” as they scramble to trigger stuns.

And then there’s the infamous “Karnov laugh”, an audio clip so ridiculous it’s become meme gold in the FGC (Fighting Game Community). These bizarre, meme-worthy elements have made Fighter’s History a staple in “so bad it’s good” conversations—yet with just enough mechanical integrity to still be fun to play.

What If It Had Hit Bigger?

It’s a question that lingers like a stunned opponent mid-combo: What if Fighter’s History had broken through? What if it had been the one to ride the wave of Street Fighter II’s success all the way to the top tier of fighting game fame? In a genre known for tight windows and tougher competition, could Data East’s scrappy contender have ever stood shoulder to shoulder with the giants?

Could it ever have dethroned Street Fighter? Probably not. By the time Fighter’s History landed in 1993, Capcom had already planted its flag, expanded its cast with Street Fighter II Turbo, and practically written the rules of the genre. Arcades were flooded with imitators, and unless you brought something revolutionary—or had SNK’s swagger and hardware—you were background noise.

Fighter’s History didn’t lack heart, but it lacked the star power, technical polish, and marketing clout that Capcom wielded effortlessly. The game didn’t innovate enough to reset the meta, nor did it create memorable mascots who could anchor a franchise. Without a Chun-Li, a Ryu, or a Guile to rally around, it was always going to be a side bet.

The early ‘90s arcade scene wasn’t forgiving. Games lived and died by quarters and word of mouth. If your fighting game was “almost as good” as Street Fighter II, you were already behind. Players wanted immediate thrills, characters that popped, and controls that felt crisp in seconds—not hours.

Fighter’s History was decent, maybe even “good,” but in a golden era packed with flashier or more stylish competition (Mortal Kombat, Fatal Fury, Samurai Shodown), being competent wasn’t enough. It didn’t turn heads, didn’t inspire rivalries, and didn’t create cultural moments. It just… existed.

If Fighter’s History had landed earlier—say, in late 1991 or early 1992—it might’ve had a real shot. A few months of breathing room before Street Fighter II Turbo or Fatal Fury 2 could’ve changed everything. Timing, in fighting games and in life, is everything.

But it wasn’t just about when—it was about how. Street Fighter II didn’t just come first, it came perfect. Its pacing, its art, its audio—all of it worked in concert. Fighter’s History, meanwhile, felt like a remix: serviceable but slightly offbeat. And in a genre where players obsess over frame data and hitboxes, that subtle gap in polish becomes a canyon.

Final Round

Let’s not sugarcoat it: Fighter’s History is undeniably derivative. From the international tournament setup to the character archetypes and six-button layout, it followed the Street Fighter II formula closely—too closely for Capcom’s liking. But derivative doesn’t always mean disposable. Beneath the familiar framework is a fighter that tried to tweak the formula in its own small, scrappy ways.

Its weak point system, while gimmicky on paper, added an extra layer of strategy. Its strange, sometimes awkward animations made matches feel unpredictable. And its characters, though often off-brand versions of Capcom or SNK favorites, had a distinct charm that grew on players willing to look past the surface.

Ironically, the lawsuit may be the reason people remember Fighter’s History at all. Capcom’s legal attack ensured the game a spot in gaming folklore, branding it forever as “that SFII clone that went to court.” But the truth is, the game had enough mechanical merit to stand on its own—at least in the second tier of arcade brawlers.

People still fire it up on Fightcade. Side tournaments still sneak it into lineups. And in an era obsessed with frame-perfect execution and complex inputs, Fighter’s History’s straightforward approach is… kind of refreshing.

It would be easy to laugh off Fighter’s History as a footnote, a punchline, a cautionary tale. But that would be selling it short. The game is more than a clone—it’s a snapshot of a chaotic, wildly creative time in gaming history, when developers were scrambling to figure out what worked, what sold, and what could capture lightning in a joystick.

It didn’t dethrone Street Fighter. It didn’t spawn a billion-dollar franchise. But it did survive, against the odds—and in doing so, it earned its place in the genre’s colorful, crowded legacy.

Final verdict? Guilty—but not without merit. Fighter’s History carved out something of a legacy—one born not of dominance, but defiance. It survived Capcom’s legal wrath, earned a sequel, and lives on through retro compilations and a loyal cult base. It may not have become a pillar of the genre, but it proved that even second-string fighters can leave a mark.

Today, Fighter’s History feels more like a snapshot of the era—a product of a time when everyone was trying to figure out what made a good fighting game tick. It didn’t innovate enough to change the genre, but it contributed just enough to earn a second look. Not a clone. Not a killer. Just a solid competitor that swung for the ring and landed a few punches of its own.

And if you’ve never played it? Pop a credit in, pick Karnov, and see what all the fuss was about. You might just find there’s more fight left in this forgotten contender than you expected.

Bonus: Fighter’s History Trivia Corner

Think you know everything about Fighter’s History? Time to put your arcade knowledge to the test. Beneath its legacy of lawsuits and low-tier memes lies a treasure trove of bizarre, wonderful trivia that ties into forgotten lore, unexpected cameos, and one of gaming’s weirdest legal sagas.

That Time Mizoguchi Showed Up in Another Fighter

Fan-favorite Mizoguchi—he of the headband, the “I’m basically Ryu but not really” energy, and the ridiculous voice clips—was so iconic (relatively speaking) that he earned a lead role in Mizoguchi Kiki Ippatsu!!, a Japan-only Super Famicom game released in 1995.

But he didn’t stop there. In 2007, Mizoguchi made a shocking guest appearance in Kenka Bancho: Badass Rumble on PSP, complete with his signature moves. While not exactly an A-list crossover, it confirmed what diehards suspected all along: Mizoguchi is forever.

How a Lawsuit Helped Define What a “Fighting Game” Is in Court

The Fighter’s History lawsuit wasn’t just tabloid fodder—it actually helped establish a legal precedent for what aspects of a video game could be protected under copyright law. When Judge William H. Orrick Jr. ruled in favor of Data East in 1994, he clarified that things like health bars, special move inputs, and international tournaments were scenes à faire—elements so common in a genre, they aren’t eligible for copyright.

This case has since been cited in academic journals, gaming law discussions, and even modern court cases, making Fighter’s History unintentionally one of the most important games in legal video game history. Not bad for a so-called clone.