When Sega unveiled the NAOMI arcade board in 1998, it didn’t just mark a technological leap—it fired a warning shot across the industry. Arcades were fading. Consoles were ascendant. But here was a machine that fused the soul of a coin-op with the brain of a console, daring to blur the lines between them. Built on the skeletal architecture of the Sega Dreamcast but jacked with double the memory, a beefier GPU, and modular muscle for scalability, NAOMI wasn’t just a successor to the Model 3—it was a system reborn for the twilight of the arcade golden age.

Capable of eye-watering visuals, near-instant load times, and cartridge-swapping efficiency, NAOMI became a lifeline for operators and a proving ground for genre-defining hits. Fighters. Racers. Bullet-hell ballet. It carried them all—and carried them with style. At a time when the arcade floor was starting to look like a museum, NAOMI brought the future roaring back, wrapped in sleek plastics and raw ambition. This wasn’t just hardware. It was a movement.

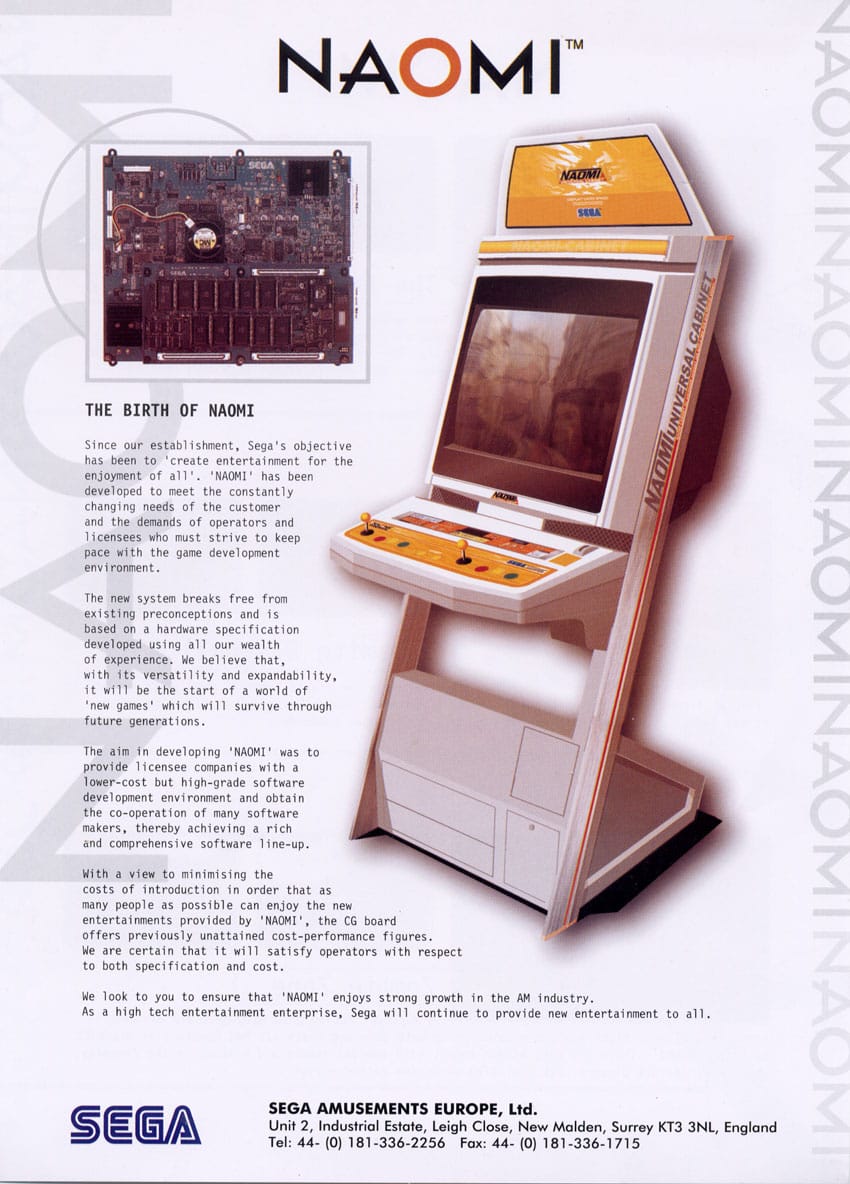

The Birth of NAOMI

By the late ’90s, the arcade scene was wobbling under the weight of its own legacy. The titanic Model 3 had pushed polygon counts to new heights, but its bespoke, high-cost hardware wasn’t sustainable for the next generation. Enter NAOMI—the New Arcade Operation Machine Idea—Sega’s answer to an industry in flux. Revealed with quiet confidence at JAMMA 1998, NAOMI wasn’t just another board. It was a bold recalibration of what arcade hardware could be: modular, affordable, and future-proof.

The first whispers came out of the Amusement Machine Show in Japan, hosted by JAMMA. While rivals were doubling down on bespoke systems and expensive upgrades, Sega unveiled a system that looked strangely… familiar. That’s because under the hood, NAOMI shared much of its architecture with the Dreamcast—a calculated move that promised easier ports, reduced development costs, and lightning-fast production cycles.

Forget soldered ROMs and weeks-long shipping delays. With NAOMI, game upgrades were as easy as popping in a new cartridge. Operators could refresh their cabinets in minutes without needing to invest in new hardware. This reduced downtime, saved money, and allowed arcade owners to chase trends or test new titles without risk. It was console-like convenience in a coin-op world—and it paid off.

Most arcade boards of the era were proprietary and closely guarded. Not NAOMI. Sega went wide, licensing the tech to former rivals like Capcom, Namco, and Taito. This move didn’t just expand NAOMI’s reach—it turned it into a near-universal standard. Developers loved the shared architecture. Operators loved the variety. And Sega? Sega built an empire off the back of a board that played nice with everyone.

A Superior Dreamcast: Specs That Still Impress

On the surface, Sega’s NAOMI and Dreamcast looked like siblings—born of the same era, built on the same silicon. But under the hood, one was bred for the arcade jungle, the other for the living room battlefield.

| Component | Specification |

|---|---|

| CPU | Hitachi SH-4 128-bit RISC @ 200 MHz (360 MIPS / 1.4 GFLOPS) |

| GPU | NEC PowerVR 2 (PVR2DC) @ 100 MHz |

| Sound Processor | Yamaha AICA ARM7-based @ 45 MHz (32-bit RISC, 64-channel ADPCM) |

| Main Memory (RAM) | 32 MB |

| Graphics Memory | 16 MB |

| Sound Memory | 8 MB |

| Storage Media | ROM Board (up to 168 MB), GD-ROM (1 GB @ 12× speed) |

| DIMM Board RAM | 8 MB to 512 MB (optional, used with GD-ROM) |

| Display Resolution | 320×240 to 1600×1200 pixels |

| Color Depth | 24-bit (16.77 million colors) |

| Polygon Performance | 2.5 million polygons/sec (realistic), up to 7 million polygons/sec (with lighting and effects) |

| Rendering Speed | 500 million pixels/sec (with transparency and effects) |

| Operating System | Sega native OS with custom Windows CE (DirectX 6.0, Direct3D, OpenGL support) |

| Controller Support | 6-button pad, 3-button pad, light gun controller |

| Compatibility | Compatible with Sega Dreamcast hardware |

| Multiboard Support | Up to 16 boards in parallel, increasing processing power significantly |

At the heart of both systems beats the SH-4, a 32-bit RISC processor capable of delivering 1.4 GFLOPS of raw computing muscle. Paired with the PowerVR2 GPU, the board featured 32MB of system RAM, 16MB of graphics RAM, and 8MB dedicated to audio.

This allowed for sharp textures, fast polygon throughput, and special effects that rivaled early sixth-gen consoles. For developers, it meant consistency across platforms. For players, it meant stunning arcade experiences that looked just like the games at home—until you noticed the fine print.

The Yamaha AICA sound system ran on its own ARM7 processor, supporting up to 64 channels of ADPCM audio. Media support came in the form of ROM boards and GD-ROMs, with backup SDR-DIMM RAM modules ensuring fast and reliable game loads.

In the age of CRT screens and scanlines, NAOMI delivered smooth 60FPS action and pushed up to 2.5 million polygons per second. With a rendering speed of 500 million pixels per second, it painted games in rich, 24-bit color—roughly 16.77 million hues in total. Whether it was explosive particle effects or richly textured 3D fighters, NAOMI kept up with (and often surpassed) early sixth-gen consoles.

NAOMI wasn’t held back by retail cost constraints. It doubled the main and graphics memory of the Dreamcast and quadrupled the sound memory, unlocking richer audio and smoother visuals. This wasn’t about saving pennies—it was about pushing pixels. Add in faster VRAM bandwidth and enhanced FPGA processing, and NAOMI quickly outpaced its living-room cousin in raw performance.

One of the key differences between the two came down to how they handled games. The Dreamcast used GD-ROMs, offering 1GB of storage but slower access times. NAOMI, by contrast, relied on hefty ROM cartridges—less capacity, but near-instant load times. In 2000, Sega gave NAOMI GD-ROM support too, marrying the best of both worlds. But in the heat of arcade competition, speed often beat out size—and NAOMI delivered blisteringly fast gameplay from the moment you dropped a coin.

Though it shared the SH-4 CPU and PowerVR2 GPU with the Dreamcast, NAOMI went harder and heavier—doubling RAM, quadrupling sound memory, and introducing FPGA-based enhancements for added processing kick. This was no home console. This was Dreamcast on steroids, primed to carry Sega’s arcade legacy into the new millennium.

Even decades later, the Sega NAOMI’s technical specs read like the blueprint for a powerhouse. It wasn’t just built to run games—it was engineered to elevate them. This was arcade tech designed with foresight, balancing raw horsepower with a modular, future-proof design that still commands respect among collectors and arcade enthusiasts today.

Variants and Innovations: Beyond the Standard Board

While the original NAOMI hardware was already a marvel of arcade engineering, Sega didn’t stop at “standard.” As the platform matured, it evolved into a chameleon-like system with multiple variants tailored for different needs—whether that meant more power, better networking, or entirely new cabinet configurations. NAOMI wasn’t just a board—it was an ecosystem.

Before the familiar white plastic casing became the norm, the earliest NAOMI units were clad in sleek aluminum shells—reminiscent of Sega’s Model 2 and Model 3 hardware. These early units featured an initial revision of the PowerVR2 GPU and were primarily distributed for location testing and developer kits. They’re rare, rugged, and now highly coveted among collectors for their pre-release mystique.

In one of the most ambitious feats of arcade engineering, Sega allowed multiple NAOMI boards to be linked in parallel—up to sixteen in theory—creating a powerhouse setup for multi-monitor, high-performance experiences. Only a handful of games took advantage of this configuration, but the results were jaw-dropping. The multiboard variant required a special BIOS and master-slave board arrangement, with a single cartridge powering the entire cluster.

NAOMI also laid the groundwork for a more connected arcade experience. With the introduction of satellite terminal setups—most famously used in Derby Owners Club—players could interact across multiple cabinets tied to a central server unit. It was part social hub, part gaming rig, and part management sim, years before online connectivity became a standard in gaming.

The NAOMI Universal Cabinet broke the mold—literally. Its streamlined, almost skeletal design stripped away bulk and focused on accessibility and performance. And thanks to its JAMMA compatibility, it played well with existing arcade infrastructure. Operators didn’t need to gut their setups to adopt NAOMI; they just had to slot it in. It was future-facing, yet backward-compatible. Stylish, yet functional.

NAOMI wasn’t just a marvel on the inside—it redefined what arcade hardware could look like. At a time when cabinets were growing dusty and dated, Sega introduced a sleeker, more modular aesthetic that was as much about visual appeal as it was about practicality. It was a system meant to evolve, to be repurposed, and to stay relevant for years—not just a single game’s lifespan.

From single-screen fighters to elaborate multi-monitor racing rigs, NAOMI was built to flex. It supported upright cabs, sit-down configurations, motion seats, and linked systems. Want to daisy-chain multiple units for a social experience? Easy. Need to hot-swap controls for a shooter or rhythm game? No problem. NAOMI was engineered like LEGO for arcade owners—modular, customizable, and shockingly easy to reconfigure.

More than just a motherboard, NAOMI was Sega’s declaration that arcade systems could—and should—function like full-fledged platforms. It wasn’t designed for a single hit or two; it was built for longevity, for experimentation, for scalability. It set the stage for what modern arcade ecosystems would later strive for: one system, endless possibilities.

Plug-and-Play Simplicity for Developers

Sega’s NAOMI didn’t just blur the line between home and arcade—it practically erased it. With a near-identical architecture to the Dreamcast, NAOMI offered console-like accessibility to developers, but with the expanded muscle and flexibility that coin-op demanded. It was the rare arcade board that felt like a dev kit and a platform all in one—one that came closer than any before it to making arcades feel like an extension of your living room.

NAOMI’s biggest strength was familiarity. For studios already working on Dreamcast titles, developing for NAOMI meant faster turnarounds and fewer surprises. Sega eliminated many of the hurdles typical of bespoke arcade systems. Tools were standardized, ports were straightforward, and the hardware was reliable. Whether you were fine-tuning hitboxes in a fighting game or optimizing texture loads in a shmup, NAOMI made the process intuitive.

Sega did something unthinkable at the time—shared its crown jewels. Capcom adopted NAOMI for Marvel vs. Capcom 2 and Capcom vs. SNK 2. Namco dabbled. Taito joined in. Even smaller studios and experimental developers got in on the action. NAOMI became a cross-industry playground, delivering a staggering diversity of titles—from twitchy 2D brawlers to sleek 3D racers and offbeat rhythm games.

Despite their architectural similarities, porting from NAOMI to Dreamcast wasn’t always plug-and-play. NAOMI had double the RAM, four times the sound memory, and faster VRAM bandwidth—not to mention the ability to load massive assets from ROM boards. On Dreamcast, sacrifices had to be made. Redbook audio had to be spooled from disc. Textures were downsampled. Some particle effects were stripped out entirely. The ports were still solid, but arcade purists could always tell the difference.

Capcom, never one to share space easily, moved beyond its aging CPS-2 and complex CPS-3 hardware to embrace NAOMI with open arms. Titles like Marvel vs. Capcom 2 and Capcom vs. SNK 2 weren’t just visually stunning—they ran smoother and loaded faster, thanks to NAOMI’s cartridge-based infrastructure. Taito got in the mix with experimental shooters like Chaos Field and Psyvariar 2, while Namco, despite its own storied arcade pedigree, utilized NAOMI hardware for collaborative ventures and licensed releases. For developers, NAOMI eliminated guesswork. No custom chips, no boutique boards—just raw, reliable power.

By leveraging the familiarity of Dreamcast architecture, NAOMI offered a level playing field. It allowed studios to focus on creative ambition rather than technical gymnastics. Development cycles shrank, hardware costs dropped, and cross-company partnerships flourished. NAOMI became the Switzerland of arcade boards: neutral, friendly, and shockingly effective at getting competitors to play nicely. In doing so, it helped unify an increasingly fractured arcade industry at a moment when cohesion was desperately needed. The result? A golden stretch of arcade releases where innovation trumped isolation—and everyone leveled up.

Top 20 Sega NAOMI Games That Defined a Generation

The Sega NAOMI wasn’t just another arcade board—it was a revolution on silicon. With its Dreamcast DNA supercharged for the arcade battlefield, it offered developers more power, more memory, and more room to experiment. The result? A treasure trove of genre-defining hits, many of which became iconic franchises or cult legends in their own right. These 20 titles represent the best of the best—games that pushed NAOMI’s limits, shaped the arcade scene, and left an undeniable mark on gaming history.

Marvel vs. Capcom 2 (2000)

The Ultimate Crossover Chaos: You want fan service? MvC2 delivered it in seismic waves. With 56 characters—from Ryu and Iron Man to obscure deep cuts like Marrow—Capcom's chaotic crossover was a fever dream made real. NAOMI’s extra RAM allowed for tag-team mayhem, lightning-fast load times, and screen-filling hyper combos that could crash older boards. It became a tournament staple, a pop culture icon, and a reason for arcade-goers to keep stacking quarters.

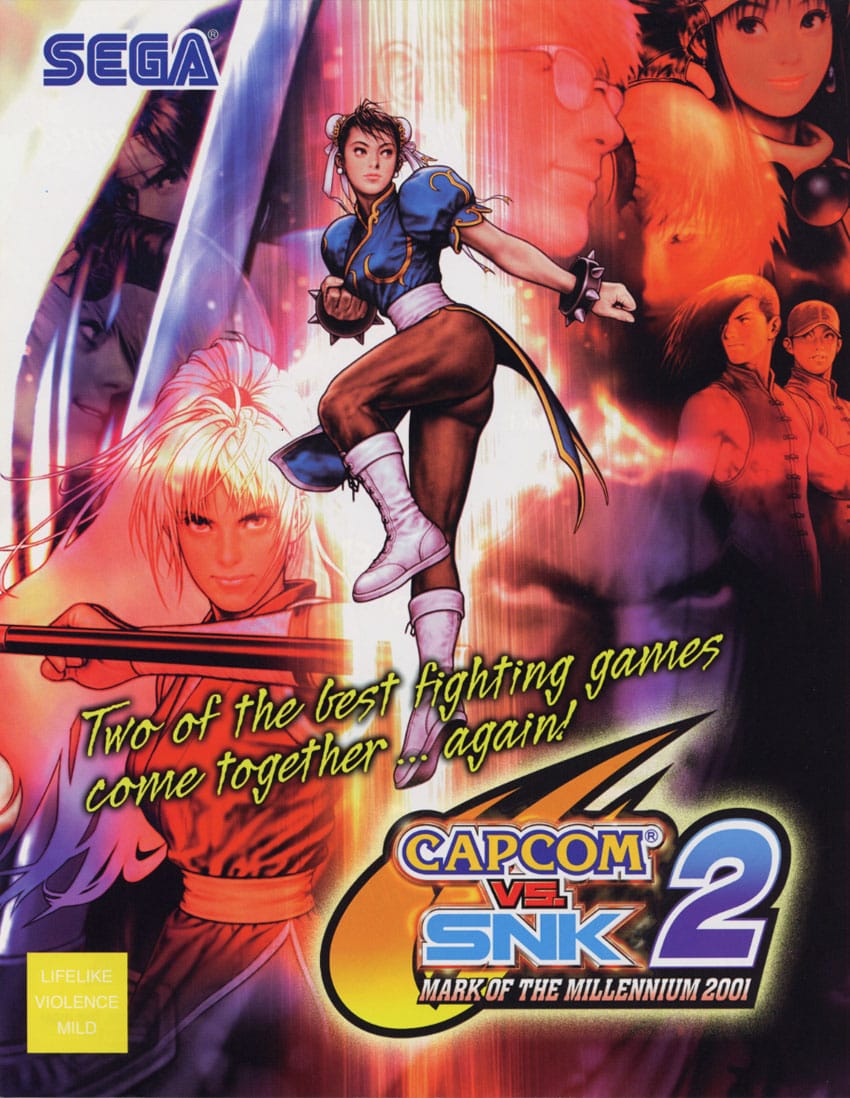

Capcom vs. SNK 2: Mark of the Millennium (2001)

Fighting Game Royalty: Where MvC2 went for bombast, CvS2 doubled down on polish and precision. With six grooves representing different fighting styles, a tight roster of SNK and Capcom legends, and some of the smoothest 2D animation ever seen in an arcade, CvS2 became a thinking man’s fighter. NAOMI gave it the muscle to handle complex systems without sacrificing speed—resulting in one of the most beloved competitive fighters ever made.

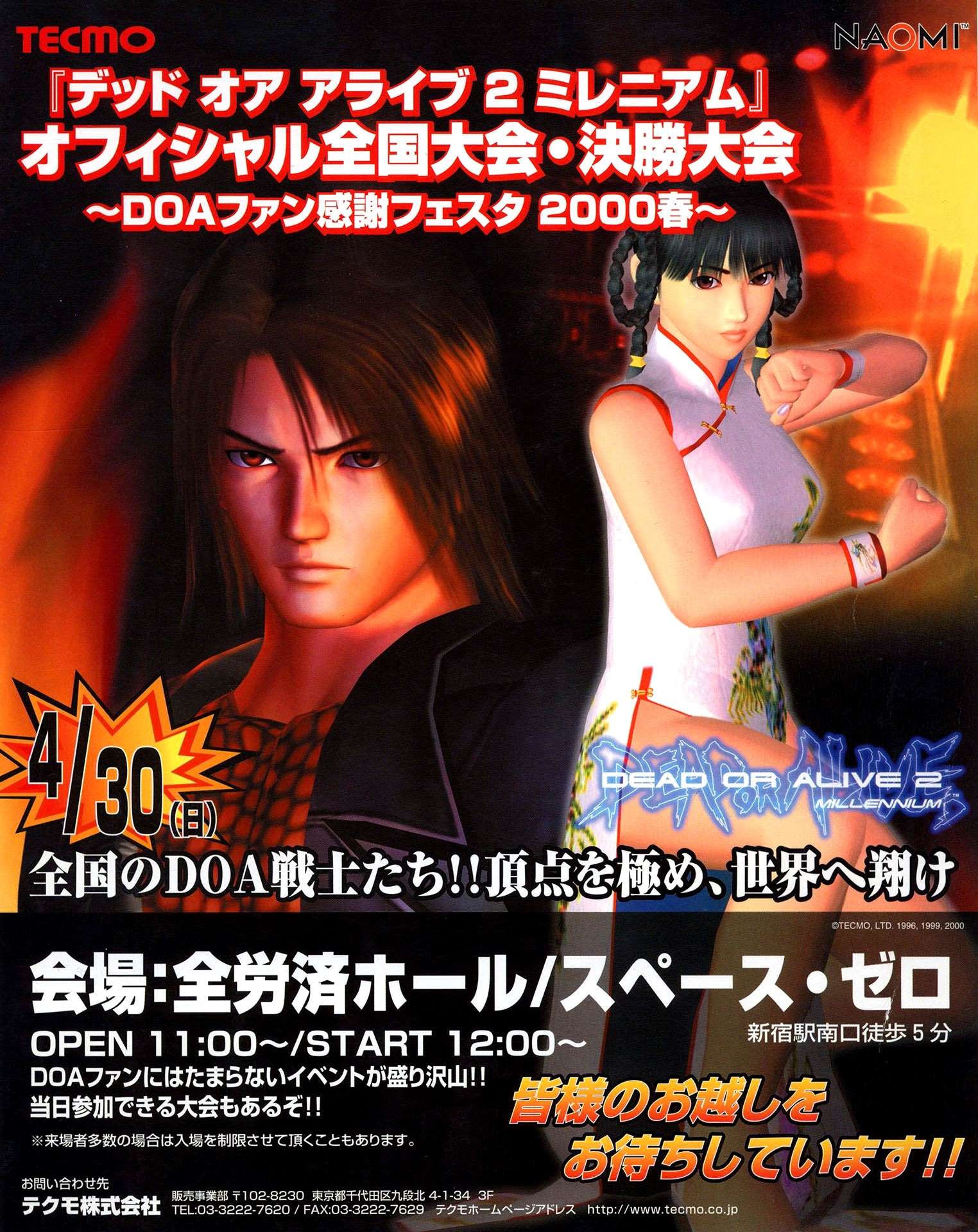

Dead or Alive 2 Millennium (2000)

Fast, Flashy, Technical: This wasn’t just about bouncing physics and slow-mo counters—DOA2 Millennium was a sleek, high-speed masterclass in reactive fighting. Built to dazzle, its dynamic stages, tag mechanics, and intuitive combo flow made it a fan favorite. NAOMI allowed Team Ninja to go bigger, cleaner, and faster than on Dreamcast, helping DOA solidify its arcade presence.

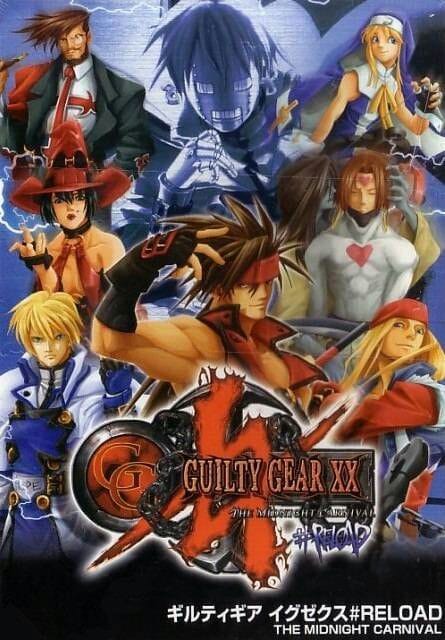

Guilty Gear XX #Reload (2003)

Heavy Metal, Heavy Mechanics: Arc System Works turned heads with its metal-infused 2D brawler. With wild character designs, air dashes, Roman Cancels, and more mechanical depth than a Gundam factory, GGXX #Reload was peak NAOMI. The system’s sprite-handling power gave these hand-drawn characters their signature slickness—each frame was a love letter to high-octane anime action.

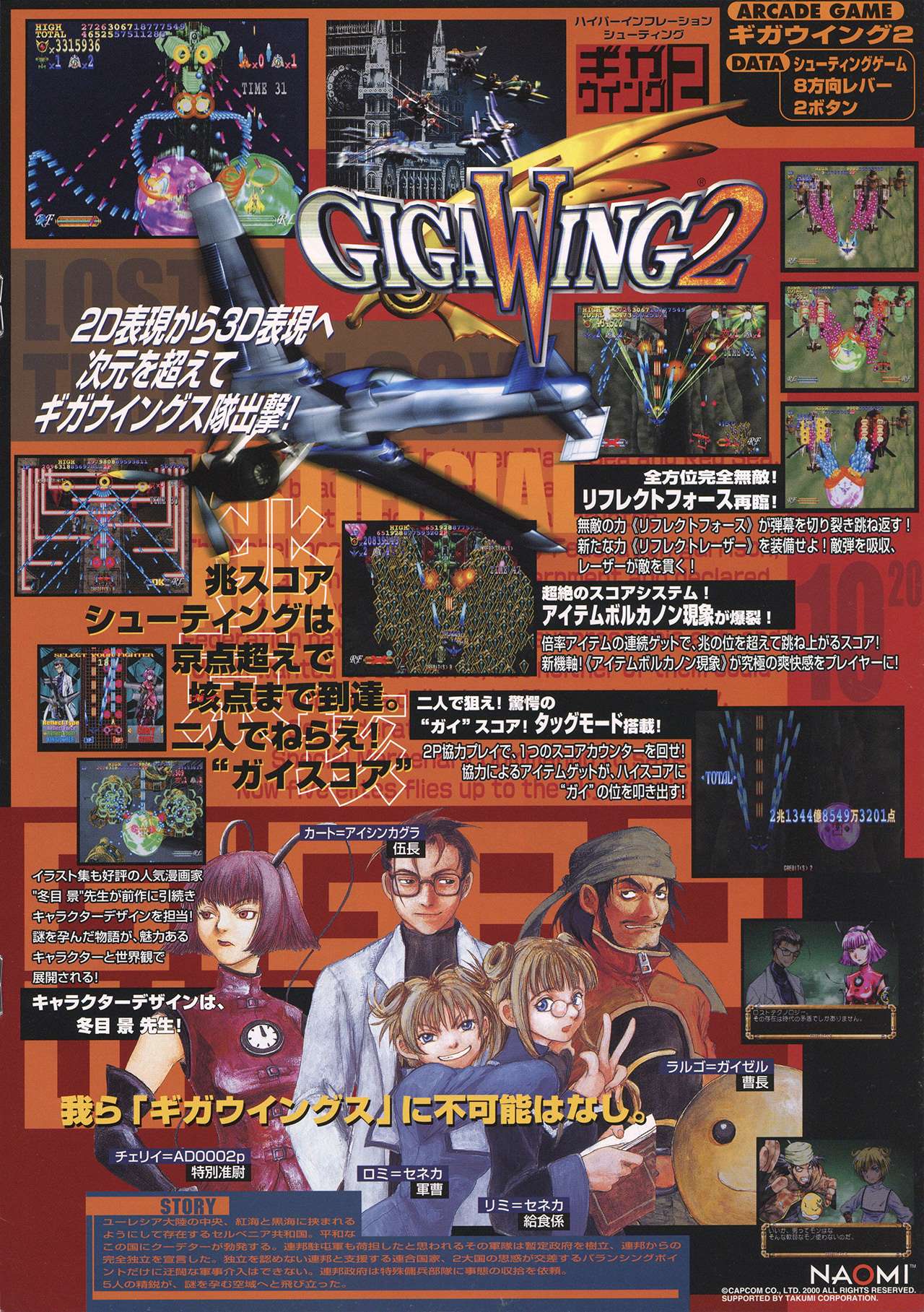

Giga Wing 2 (2000)

Bullet Hell Brilliance: Capcom’s vertical shmup sequel upped the ante in every way. Bombs? Who needs ’em when you have the reflect force—your ticket to weaponizing enemy fire. Giga Wing 2’s particle-rich chaos would’ve choked weaker hardware, but NAOMI turned it into hypnotic, symphonic destruction. A feast for the eyes, ears, and twitch reflexes.

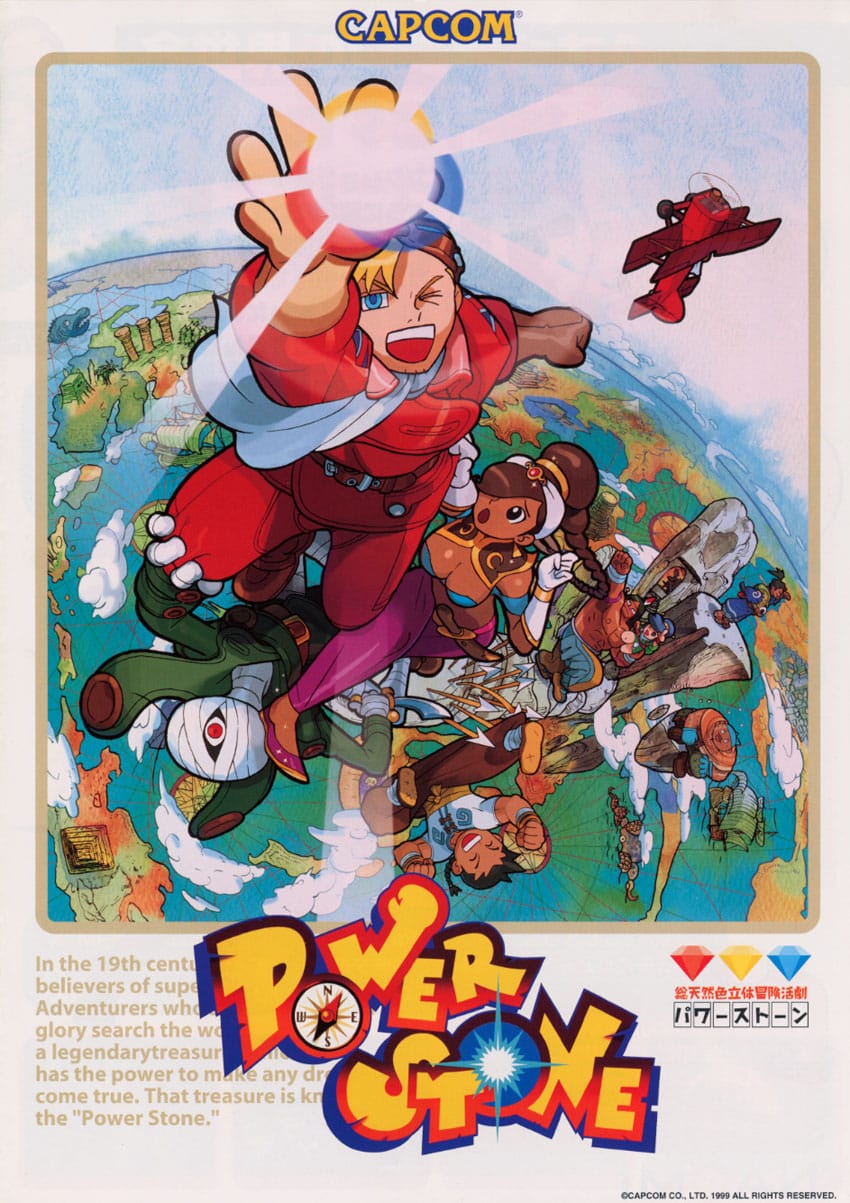

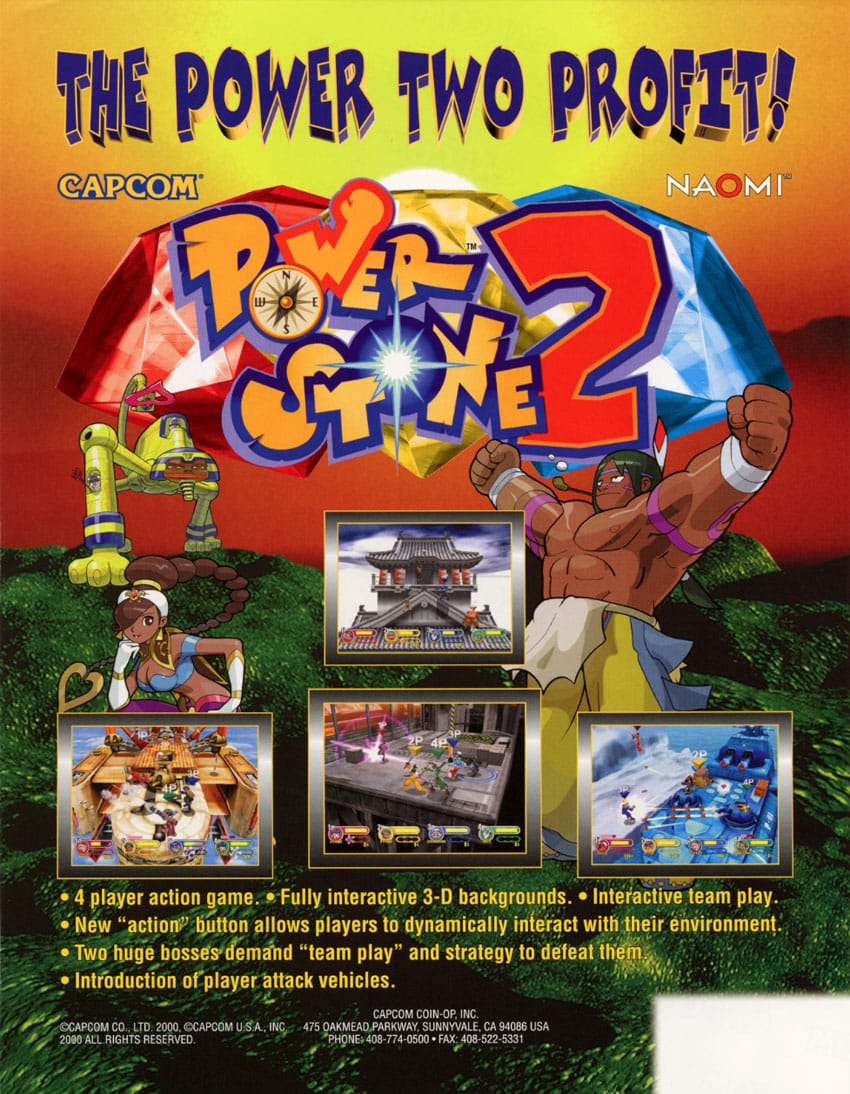

Power Stone & Power Stone 2 (1999-2000)

Arena Fighters at Their Wildest: Before Smash Bros ruled the party brawler space, Power Stone laid the blueprint. These 3D arena brawlers blended isometric chaos with pick-up-and-play simplicity. The sequel added 4-player mayhem, transforming stages, and weaponized nonsense that turned every match into Saturday morning cartoon warfare. NAOMI gave these games the smoothness and speed they needed to become all-timers.

Project Justice (2000)

Rival Schools Graduate With Honors: Capcom took its cult classic Rival Schools and cranked it up to 11. Bigger combos, wilder team-up moves, and a more mature story gave Project Justice its own identity. On NAOMI, it shed its PS1 limitations and fully realized its bold 3D anime-fighter potential. It was slick, stylish, and tragically underplayed outside Japan.

Psyvariar 2: The Will To Fabricate (2003)

Risk-Based Shooting Redefined: Forget just dodging bullets—Psyvariar 2 dared you to graze them. Every near-miss powered you up, encouraging risky play and split-second precision. Its leveling mechanic made it one of the most replayable shmups of the era. NAOMI’s tech let Success Corp fill the screen with hypnotic patterns that never slowed down, never stuttered—just pure, buttery smooth bullet hell.

Mobile Suit Gundam: Federation vs. Zeon DX (2001)

Mecha Mayhem: Two-player co-op? Try four-player mech battles with tanks, beam sabers, and orbital strikes. This was Gundam done right—tight controls, tons of suits, and full-scale battlegrounds that felt alive. NAOMI’s ability to handle large 3D spaces and dynamic AI gave this game a tactical feel rarely seen in arcades.

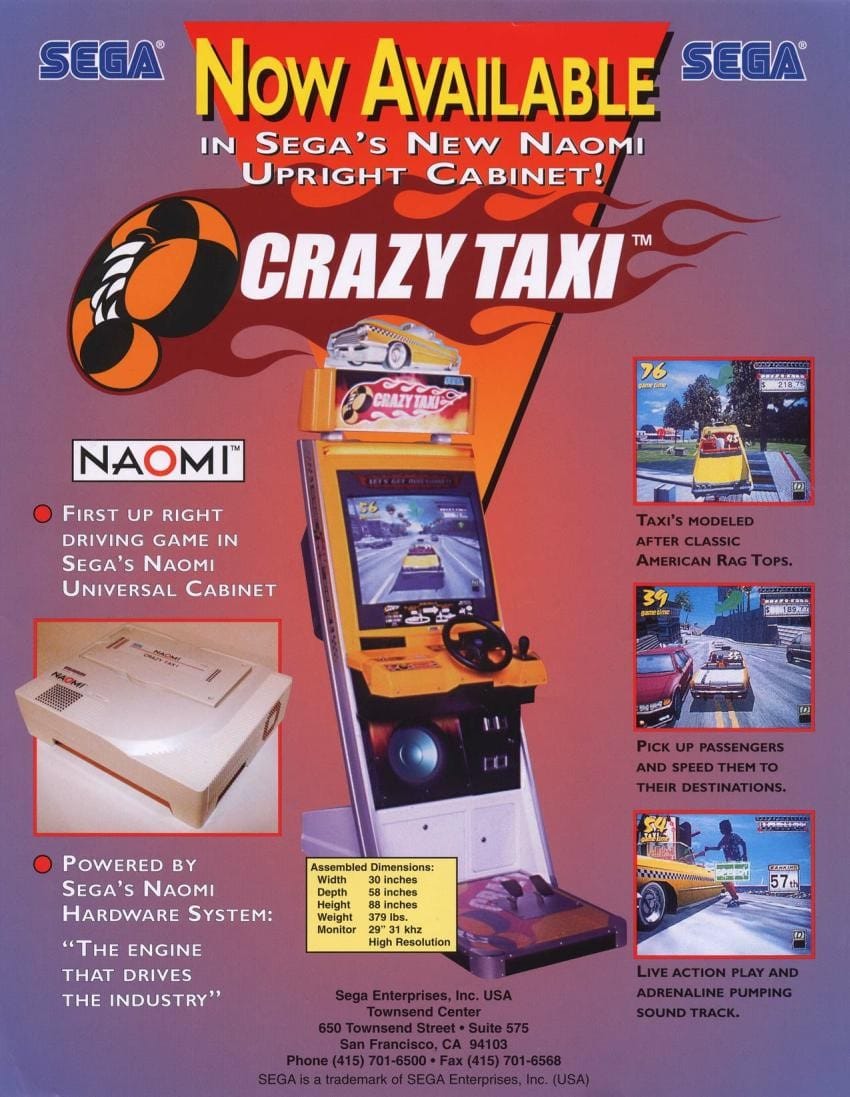

Crazy Taxi (1999)

Drive Like You Mean It: Pick up passengers, dodge traffic, and launch your cab off a pier—all while blasting The Offspring. Crazy Taxi was pure, unfiltered arcade energy. Thanks to NAOMI, it loaded fast, ran flawlessly, and kept your adrenaline maxed out at all times. A coin-op juggernaut that proved arcade racers could still innovate.

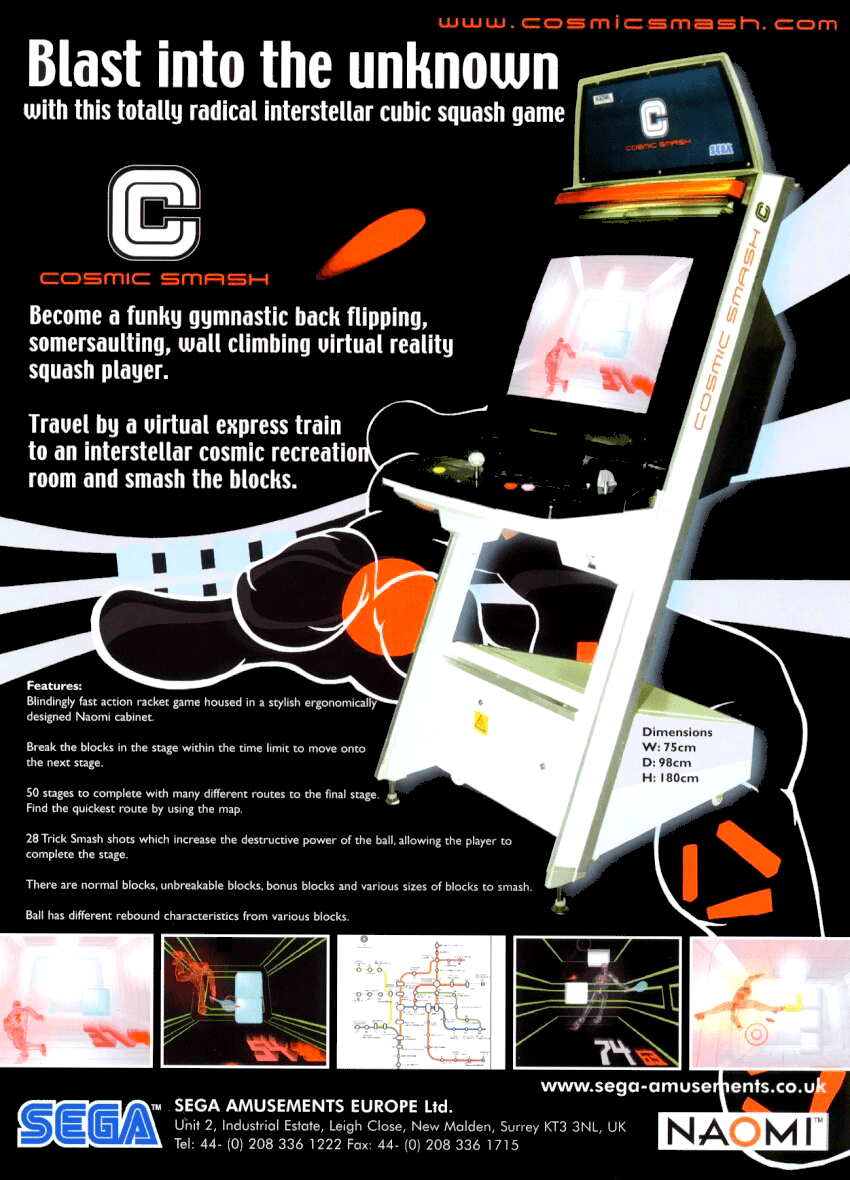

Cosmic Smash (2001)

Minimalism Meets Motion: Cosmic Smash looked like Rez met Virtua Tennis in an art gallery, and played like a psychedelic brick-breaker in zero gravity. NAOMI’s horsepower allowed for sleek lighting effects, fluid animation, and surreal audio design. It wasn’t a blockbuster, but it was a cult classic in the making.

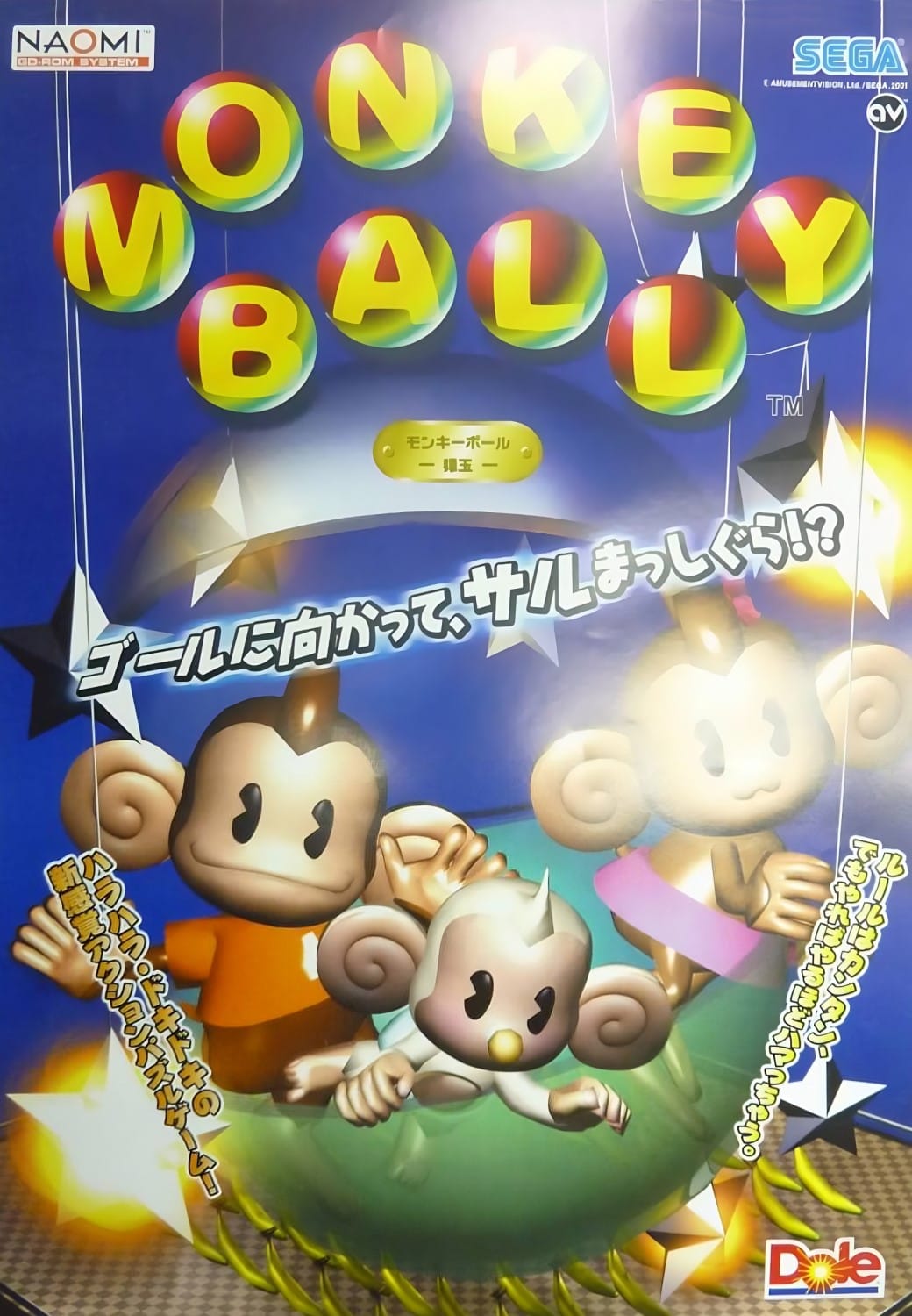

Monkey Ball (2001)

The Arcade Origins of a Party Icon: Long before bananas and minigames became household staples, Monkey Ball was a razor-sharp arcade balancing act. Tilt the world, not the ball. The analog precision required was brutal—but addictive. NAOMI’s smooth framerate and responsive input made it a showcase of physics-based design in its infancy.

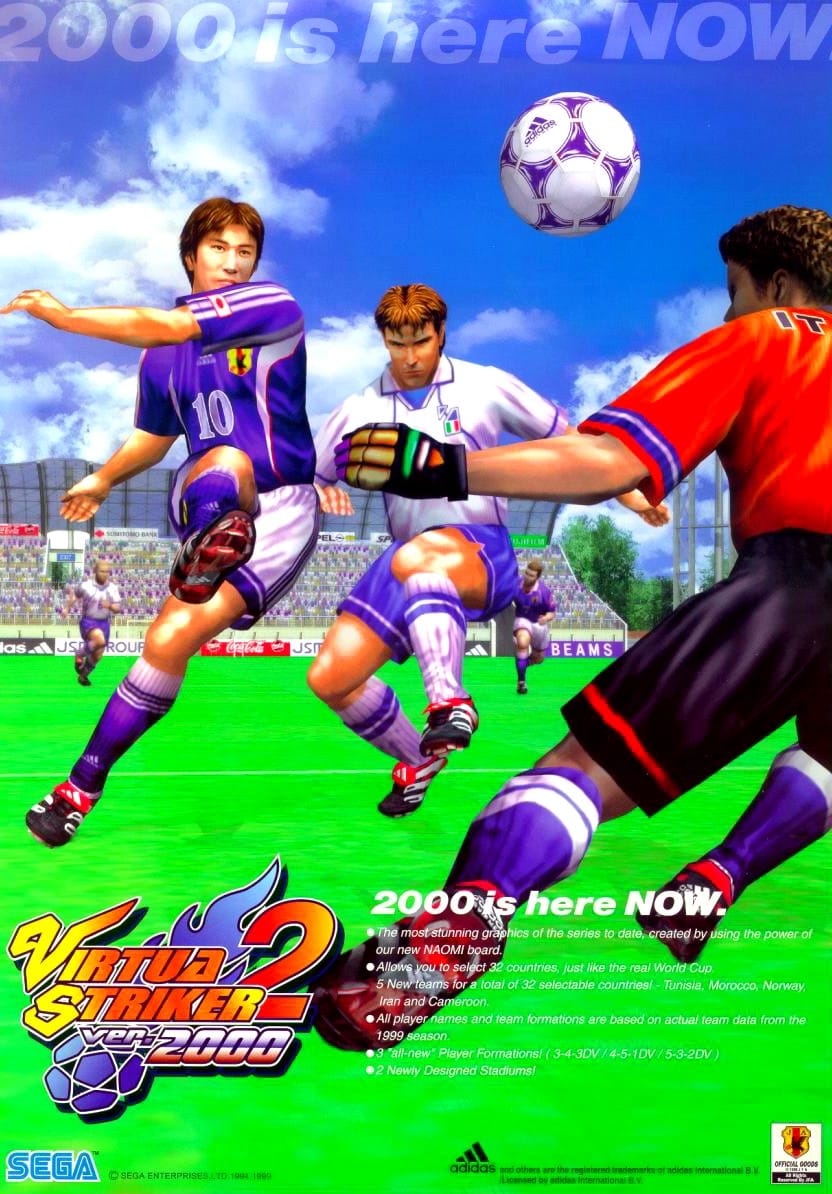

Virtua Striker 2 Ver. 2000 (1999)

Soccer Goes Hardcore: Forget sim. This was arcade football—fast, aggressive, and absolutely ruthless. Beautiful animations, satisfying tackles, and the occasional superhuman goal. NAOMI’s graphical punch helped Virtua Striker hold its own in smoke-filled Japanese game centers packed with sports fanatics.

Ikaruga (2001)

Black & White Bullet Ballet: Elegance in chaos. Treasure’s polarity-shifting masterpiece redefined what a shmup could be. It was more puzzle than twitch reflex, more brain than brawn. NAOMI made it possible, handling the duality mechanic, complex bullet patterns, and razor-sharp visuals without breaking a sweat.

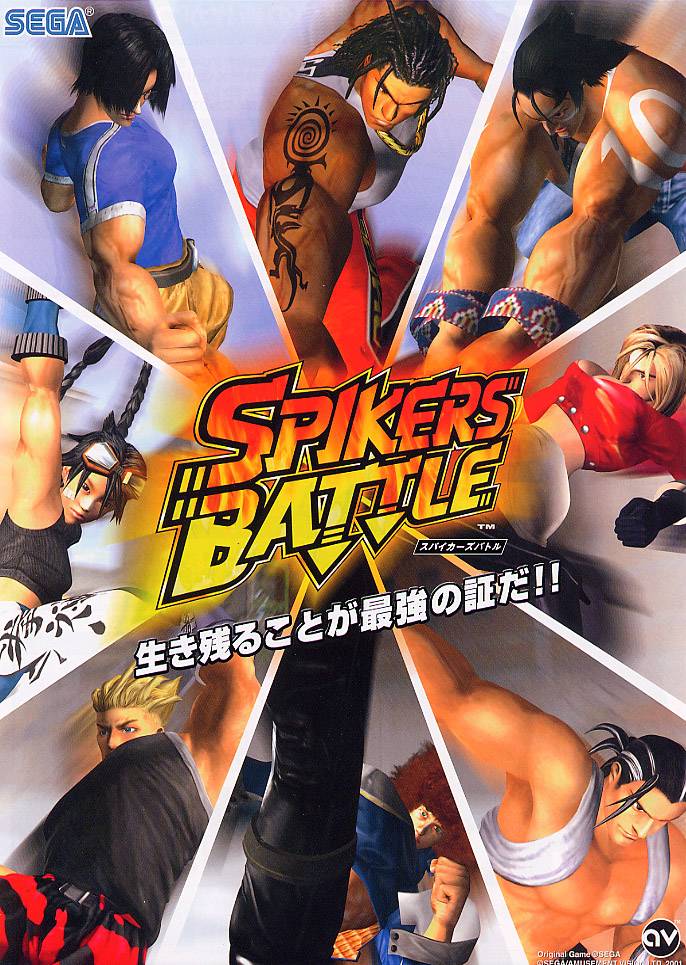

Spikers Battle (2001)

The Forgotten Sports Gem: Volleyball never looked this good. With anime flair, smooth animation, and shockingly deep gameplay, Spikers Battle stood out in a sea of fighters and racers. It wasn’t a massive hit, but for fans lucky enough to find it, it was arcade gold—and proof NAOMI could do any genre.

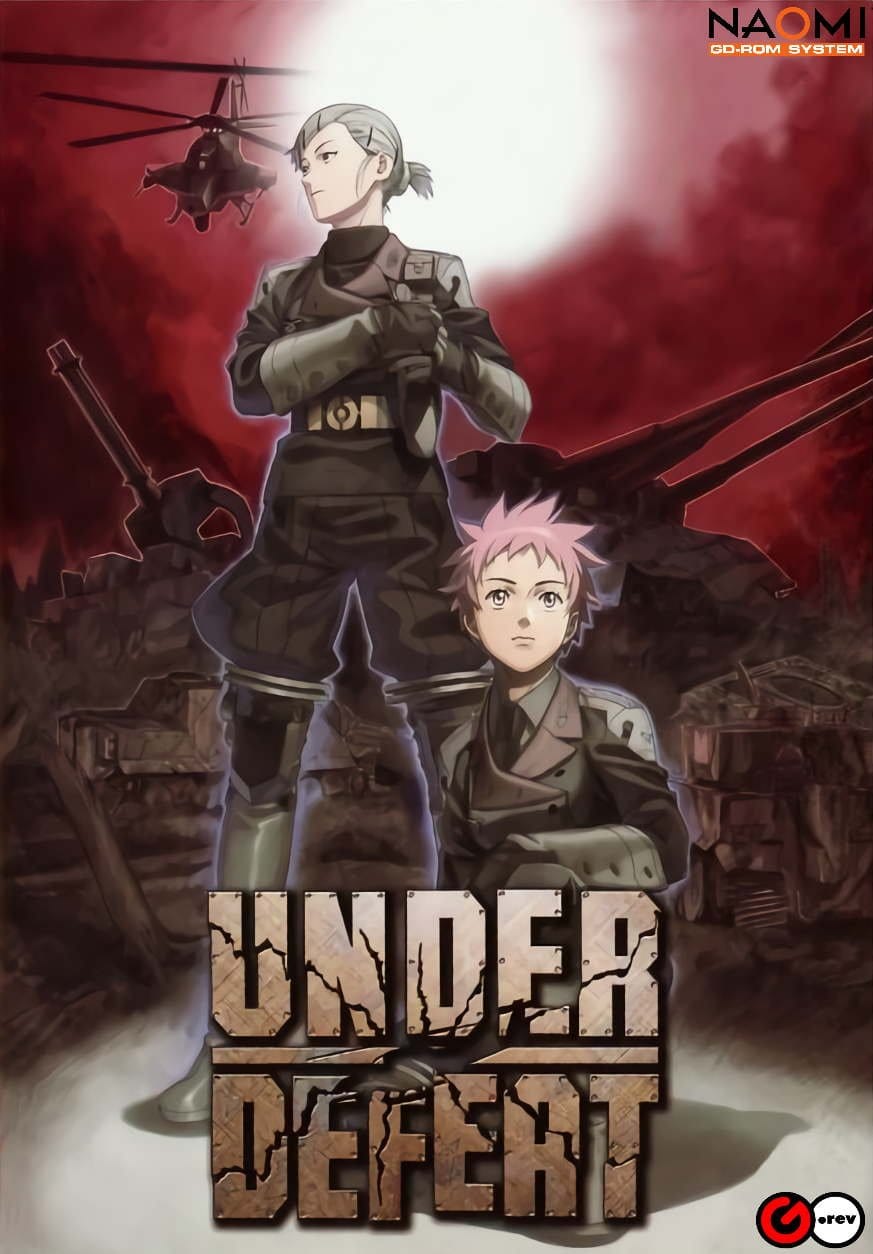

Under Defeat (2005)

A Shmup With Grit: Under Defeat swapped neon lasers for chopper gunships and military realism. Its tilted perspective, weighty feel, and explosive effects made it a standout late-era NAOMI title. It looked good enough to be next-gen—and still does.

Chaos Field (2004)

Psychedelic Shmup Action: Boss after boss. That’s it. Chaos Field was a boss-rush shooter drenched in abstract visuals and high-risk weapon switching. NAOMI's muscle allowed for massive, complex enemy designs and blistering speed. It wasn’t for everyone, but for the hardcore? Pure eye-candy carnage.

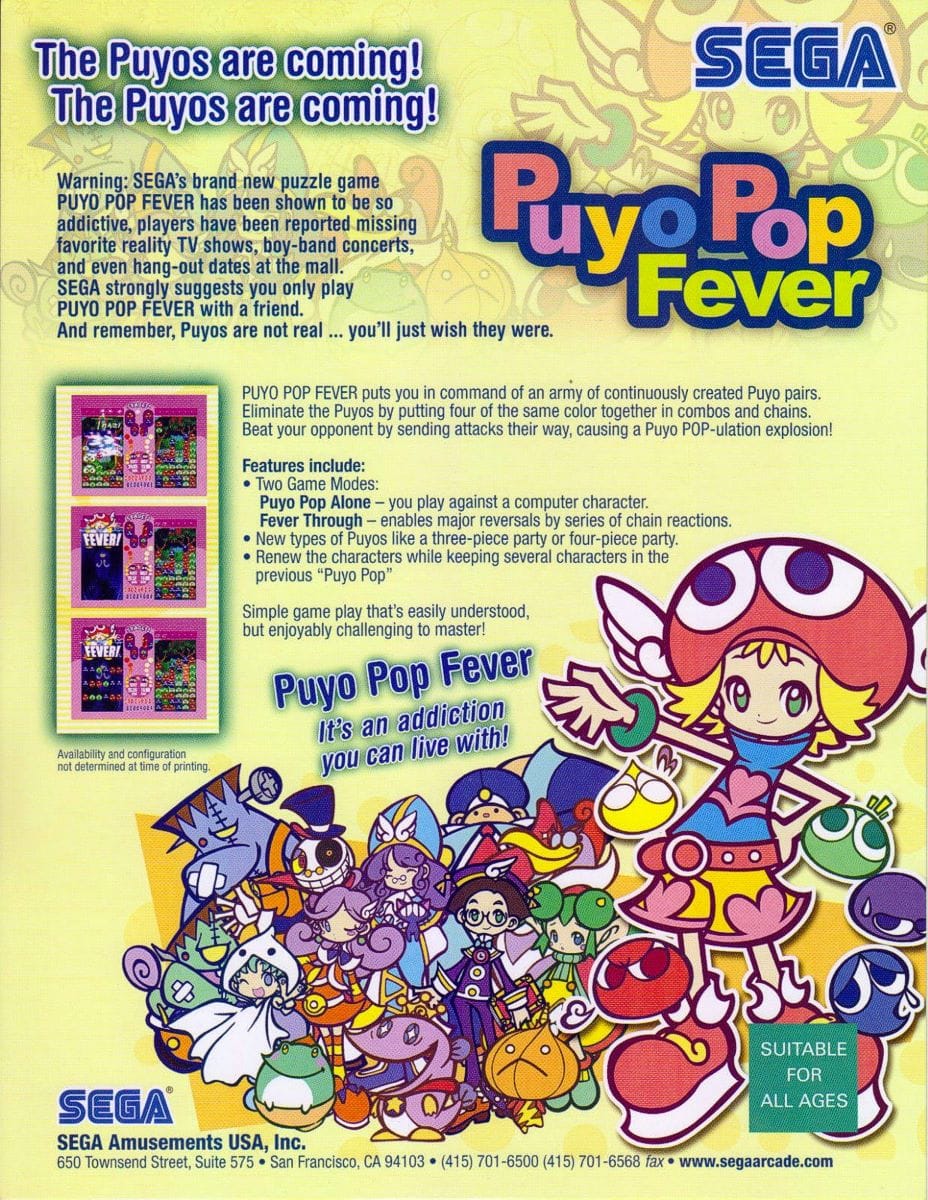

Puyo Puyo Fever (2003)

Puzzle Perfection: Cute characters, bright visuals, and cutthroat chains. Fever brought a new twist to Puyo mechanics, giving the NAOMI an arcade puzzle star. It was fast, fluid, and devilishly competitive—everything a great arcade puzzler should be.

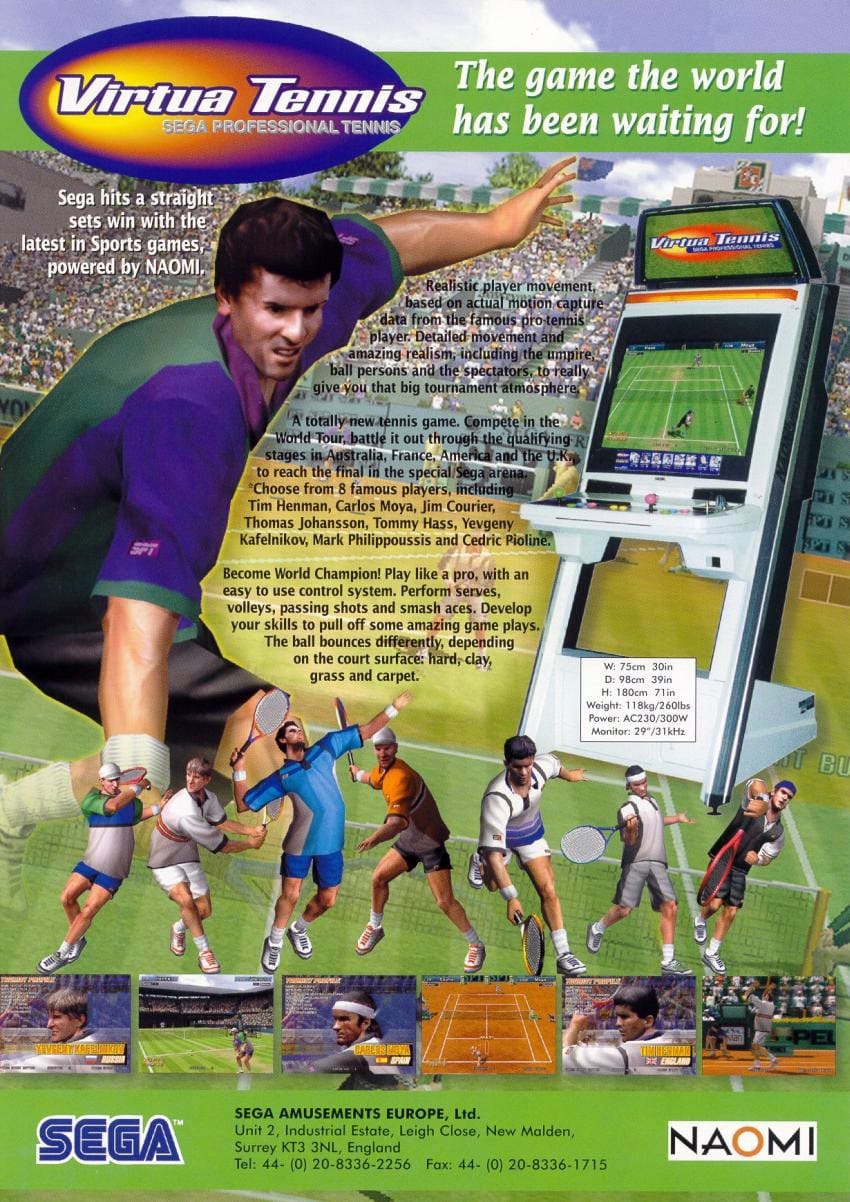

Virtua Tennis (1999)

Arcade Sports at Peak Precision: Whether you were battling the CPU in a tense tiebreak or going head-to-head with friends for bragging rights, Virtua Tennis nailed that hard-to-achieve middle ground between simulation and arcade fun. It wasn’t just a good sports game—it was an essential arcade experience, one that would go on to launch a franchise beloved on the Dreamcast and beyond.

From bullet hell to tag-team brawlers, NAOMI’s lineup was an embarrassment of riches. It wasn’t just about specs—it was about enabling vision. Developers used NAOMI’s robust toolkit to take chances, remix genres, and create arcade games that didn’t just entertain—they endured. These 20 titles prove one thing: NAOMI wasn’t just an arcade board. It was a platform for greatness.

NAOMI’s Legacy on Consoles

When arcade-goers first experienced Crazy Taxi, Power Stone, or Marvel vs. Capcom 2 on the Sega NAOMI board, they were witnessing more than cutting-edge gameplay—they were previewing the Dreamcast’s future. Built on a shared technological backbone, NAOMI and Dreamcast were two sides of the same silicon coin. But while one lit up arcade floors with blistering performance and modular design, the other brought that magic into living rooms—often with a few hard compromises.

The Dreamcast’s stellar early lineup wasn’t just inspired by NAOMI—it was NAOMI. Nearly every arcade smash that graced the board between 1998 and 2001 found its way home, forming the core of Sega’s console offensive. Fighters like Dead or Alive 2 and Project Justice, racers like 18 Wheeler: American Pro Trucker, and wildcards like Cosmic Smash and Puyo Puyo Fever gave the Dreamcast a flavor no other console could match: unapologetically arcade-first.

But the ports weren’t always perfect. With NAOMI packing more RAM and better texture handling than its home-bound sibling, devs had to make brutal decisions. Music was compressed. Animations were trimmed. Visual effects like dynamic lighting or anti-aliasing were dialed back. Some games lost frames; others lost entire modes. Yet, remarkably, the core experience usually survived intact—still fast, still fluid, and still faithful to the arcade original.

Some conversions didn’t just survive the leap—they evolved. Ikaruga added extra modes and polish. Marvel vs. Capcom 2 brought home an astonishing 56-character roster with barely a hiccup. Virtua Tennis became a couch co-op staple. These weren’t watered-down shadows—they were full-fat ports that turned the Dreamcast into a de facto arcade cabinet. NAOMI gave Sega the tools. The Dreamcast made them personal. And together, they rewrote the rules of arcade-to-home synergy.

NAOMI’s Decade-Long Dominance (1998–2009)

While most arcade boards burned bright and faded fast, NAOMI played the long game—quietly powering some of the biggest hits in arcades for over a decade. From its 1998 debut to its final run in the late 2000s, Sega’s powerhouse outlived rivals, redefined expectations, and became the go-to platform for developers who wanted flexibility without sacrificing visual flair. In an industry notorious for short hardware cycles, NAOMI stood tall—and stood long.

When NAOMI launched, it was rubbing shoulders with aging Model 3 boards, Namco’s System 12, and a slew of proprietary setups that offered limited life spans. By 2009, many of those competitors had long since disappeared, yet NAOMI continued chugging along, still powering arcade favorites and earning floor space around the globe. Its smart architecture, easy upgrades, and enduring performance made it the default workhorse for a generation.

Whether you were throwing fireballs in Capcom vs. SNK 2 or drifting through Crazy Taxi, NAOMI handled it all with grace. It wasn’t pigeonholed by genre. 2D fighters, 3D brawlers, shmups, puzzlers, rhythm games—it supported them all without compromise. Developers didn’t have to fight the hardware—they got to play with it. And players reaped the benefits, one quarter at a time.

More than just specs and licenses, NAOMI’s legacy lies in its vision. Sega built it to endure—and it did. Its modular design, shared architecture with Dreamcast, and willingness to open its arms to third parties made it one of the most forward-thinking arcade platforms ever released. NAOMI wasn’t just a board. It was a milestone. And its impact is still felt in the arcade cabinets—and console ports—that followed.

Conclusion

In the grand pantheon of arcade hardware, few systems command the reverence—or the resume—of Sega’s NAOMI. It wasn’t just a board; it was the board. The last great industry standard before arcades splintered into proprietary hardware and niche cabinets. From 1998 through the late 2000s, NAOMI powered the pulse of the scene, from Tokyo arcades packed with salarymen to dusty corners of Western pizza parlors still clinging to their last Virtua Tennis machine.

It married power with accessibility. Scalability with stability. And most importantly, it created a common ground where Sega, Capcom, Namco, and Taito could all play together—without compromising vision or performance. That unification gave rise to an era of fighting game dominance, bullet hell brilliance, and multiplayer mayhem that still defines the genre’s DNA today.

Even now, NAOMI refuses to fade. It thrives in the hands of collectors who lovingly restore cabinets. It lives in the work of modders pushing custom NetBoot setups. And it echoes in every fighting game revival, indie arcade throwback, and Dreamcast retrospective. NAOMI wasn’t just Sega’s swan song for the arcade era—it was the gold standard. And in many ways, it still is.