The Nintendo 64 was a technical marvel—and a commercial misstep. While Mario 64 rewrote the rules of 3D gaming and The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time carved itself into history, behind the curtain, the industry was shifting. Fast. Nintendo’s decision to cling to cartridges wasn’t just old-fashioned—it was costly. Literally. By the time the PlayStation became a global phenomenon, Nintendo had lost more than third-party support—it had lost the industry’s trust. The result? A fractured ecosystem and a reputation teetering between legacy and irrelevance.

Enter the Nintendo GameCube—a compact, purple powerhouse designed to reclaim lost ground. Promising better hardware, easier development, and a more affordable price, it seemed poised to rewrite Nintendo’s fortunes. But despite its impressive specs and a library bursting with classics, the Cube stumbled. Missteps in timing, marketing, and third-party support left it outpaced by Sony’s juggernaut and Microsoft’s rising Xbox. The result was a console that gamers adored, yet the wider market largely ignored—a beloved underdog whose story is as fascinating as it is cautionary.

Project Dolphin Begins

The Nintendo 64 was a marvel of engineering. Super Mario 64 rewrote the rules of 3D platforming, and The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time became a benchmark for storytelling and gameplay. But brilliance on the screen couldn’t mask the console’s commercial struggles. Delays, limited storage capacity, and the high cost of cartridges meant Nintendo lost ground to Sony, which was quickly establishing itself as the new king of the console market.

Nintendo doubled down on cartridges when everyone else was moving to CDs. While cartridges offered faster load times and greater durability, they were expensive to produce and held far less data. Heavyweights like Square, Enix, and Capcom turned to Sony, attracted by cheaper production, larger storage, and fewer restrictions. Nintendo’s insistence on control backfired, leaving its library rich in exclusives but poor in third-party support.

Sony’s PlayStation offered developers freedom, flexibility, and a massive audience, quickly establishing the PlayStation as the console to bet on. What had once been a platform-first, developer-friendly company now found itself sidelined, setting the stage for the GameCube’s uphill battle.

Nintendo’s next console began life under the codename Dolphin. At E3 1999, Nintendo teased fans with just enough to spark feverish speculation. The company promised a powerful machine designed to correct the sins of the Nintendo 64: stronger hardware, easier development, and a cheaper manufacturing model. The reveal didn’t show much, but the mere hint of a sleek new era was enough to send imaginations racing.

With Sony’s PlayStation 2 already dominating headlines, Nintendo’s goal was clear—outgun the competition. The Dolphin was pitched as a system that would be both more powerful and more affordable, a dangerous combination in the console wars. By partnering with IBM for the CPU and ArtX (later acquired by ATI) for the GPU, Nintendo secured serious tech muscle. The message was simple: this time, Nintendo wasn’t just catching up—they were preparing to leap ahead.

One of the loudest applause lines wasn’t about raw power—it was about storage. After years of frustration with costly cartridges that limited game size and drove developers into Sony’s arms, Nintendo finally abandoned ROM-based media. The Dolphin would use proprietary mini-discs, a move that promised cheaper production and more developer freedom. To fans, it was proof that Nintendo had learned from its past mistakes. To third parties, it was a sign of hope—though, as history would show, not a guarantee of lasting support.

Building the Hardware

To give the GameCube real teeth, Nintendo enlisted some heavy hitters. IBM crafted the custom “Gekko” CPU, while ArtX—later absorbed by ATI—developed the “Flipper” GPU. Together, they produced a machine that could push advanced visuals, rich textures, and smooth performance. On paper, the Dolphin was more than capable of keeping pace with Sony’s PlayStation 2 and even standing shoulder-to-shoulder with Microsoft’s powerhouse Xbox. It was compact, efficient, and surprisingly elegant in its architecture.

The Nintendo 64 was infamous among developers for its steep learning curve, tricky hardware, and restrictive cartridge format. Nintendo knew they couldn’t repeat that mistake. The Dolphin’s architecture was designed to be far more accessible, with tools that allowed studios to harness its power more quickly. For once, Nintendo was actively trying to make life easier for developers. But with the damage already done during the N64 years, winning back trust would prove far more difficult than just fixing the tech.

If Sony’s PlayStation 2 was a sleek black monolith and Microsoft’s Xbox a hulking VCR, Nintendo went the opposite direction: small, square, and playfully purple. Complete with a carry handle, the Dolphin looked like a toy chest rather than a serious multimedia device. Fans adored its quirky personality, but in an era when consoles doubled as entertainment hubs, the Dolphin’s toy-like aesthetic made it easy for critics to dismiss. It was bold and distinctive—but it also reinforced the notion that Nintendo wasn’t playing the same game as its rivals.

When Nintendo first sent out Dolphin dev kits, the plan was to give key studios an early jump on shaping the console’s future. But supply was scarce. Only a handful of teams—like Nintendo EAD, Rare, Retro Studios, and NST—had access at first, while most third parties were left waiting. The shortage meant that by the time Dolphin kits trickled out more widely, the competition was already miles ahead, with studios heavily invested in PlayStation 2 projects. For publishers, the message was clear: Nintendo was, once again, late to the party.

The timing couldn’t have been worse. By the early 2000s, developers were already pouring resources into Sony’s PS2 juggernaut and preparing for Microsoft’s big-budget Xbox debut. With Dolphin kits hard to come by and Nintendo’s final specs still shifting, many studios didn’t bother. Why gamble on a system with an uncertain future when Sony offered a massive, growing audience and Microsoft was dangling new online possibilities? The window to win back third-party faith was closing—and fast.

The Missed Launch Window

Nintendo had sworn it wouldn’t repeat the mistakes of the N64’s troubled rollout. Yet, history has a way of echoing. While Sony’s PlayStation 2 was flying off shelves and Microsoft’s Xbox was gearing up for its own launch, Nintendo quietly pushed back its plans. Holiday 2000 came and went without Dolphin on the shelves. The company cited a lack of software as the reason, encouraging fans to keep buying N64 titles in the meantime. For players hungry for next-gen Nintendo, it felt like déjà vu—another delay, another missed opportunity to strike first.

When Nintendo finally lifted the curtain at its Space World event in August 2000, Dolphin had officially transformed into the GameCube. The reveal was met with curiosity and excitement—the compact design, the purple casing, and the quirky handle were unlike anything else on the market. Nintendo promised power, affordability, and a focus on pure gaming. But behind the applause was a nagging reality: the console wouldn’t launch until late 2001, well after Sony had cemented its dominance.

The showstopper of Space World was Mario 128, a tech demo that demonstrated the system’s muscle. Hundreds of tiny Marios scurried across the screen, platforms shifted and bent underfoot, and the audience marveled at what the GameCube could do. Fans naturally assumed this was the next big Mario adventure. It wasn’t. Mario 128 never became a full game, though its concepts lived on in Pikmin and later Super Mario Galaxy. What was meant as a statement of intent instead became a symbol of unfulfilled promise—Nintendo could dazzle with ideas, but delivering them in a timely, market-shaking way was another story.

Then came a moment that crystallized Nintendo’s attitude toward outsiders. In a December 2000 interview with NextGen magazine, company spokesman Hiroshi Imanishi declared:

“We are not approaching [third parties] and asking them to make software for Nintendo. If they would like to make GameCube software, that’s fine, but we will never demand them to make games for GameCube.”

The statement echoed Nintendo’s long-standing belief that first-party titles could carry a system until third parties eventually followed. But the industry had changed. Developers were now courted, incentivized, and treated as partners by Sony and Microsoft. Nintendo’s stubborn indifference only deepened the divide, making the GameCube an afterthought for many publishers before it had even launched.

Launching the GameCube

The GameCube made its debut in Japan on September 14, 2001, followed by North America two months later and Europe the following spring. While the staggered rollout gave Nintendo time to fine-tune logistics, it also meant losing momentum in the West—where the PlayStation 2 was already a cultural phenomenon and Microsoft’s Xbox was mounting a flashy debut. By the time the GameCube arrived, the competition had already captured headlines and mindshare.

The GameCube was a compact, powerful, developer-friendly console that excelled in gameplay and first-party support but sacrificed storage, media flexibility, and multimedia features compared to its competitors.

| Spec | Nintendo GameCube | Sony PlayStation 2 | Microsoft Xbox |

| Launch Year | 2001 (JP/NA), 2002 (EU) | 2000 (JP/NA), 2002 (EU) | 2001 (NA), 2002 (JP/EU) |

| CPU | IBM “Gekko” 485 MHz (PowerPC-based) | “Emotion Engine” 294 MHz (MIPS R5900) | Intel Pentium III-based 733 MHz |

| GPU | ATI “Flipper” 162 MHz | Graphics Synthesizer 147 MHz | Nvidia NV2A 233 MHz |

| System RAM | 24 MB 1T-SRAM + 16 MB DRAM (40 MB total) | 32 MB RDRAM | 64 MB DDR SDRAM |

| Video Output | Up to 480p (Progressive Scan, component support) | Up to 480i (480p with select titles via component cable) | Up to 480p (480i standard, 720p/1080i for some titles) |

| Media Format | Proprietary 1.5 GB Mini-DVD discs | DVD-ROM (4.7 GB single-layer, 8.5 GB dual-layer) | DVD-ROM (4.7 GB / 8.5 GB dual-layer) |

| Storage / Memory Cards | 59–1019 block Memory Cards (up to 128 MB) | 8 MB Memory Card (expandable via third party) | 8–10 GB Internal Hard Drive + Memory Cards |

| Controllers | GameCube Controller (2 analog triggers, C-stick, rumble built-in) | DualShock 2 (pressure-sensitive buttons, vibration) | “Duke” (later Controller S) with dual analog, triggers, and built-in slots |

| Networking | Optional 56k Modem or Broadband Adapter | Optional Network Adapter (dial-up/broadband) | Built-in Ethernet (Xbox Live support) |

| Backward Compatibility | None | Plays original PlayStation discs | None |

| Multimedia | Game-only device (no DVD/CD playback) | DVD/CD playback (remote required for DVD in some regions) | DVD/CD playback (remote required for DVD playback) |

| Launch Price | $199 USD | $299 USD | $299 USD |

The GameCube ran on IBM’s custom Gekko CPU, a 485 MHz PowerPC-based processor. Faster than the PS2’s Emotion Engine, it offered developers solid computational power without being overly complicated. While not as brute-force strong as the Xbox’s 733 MHz Pentium III, the Gekko struck a balance between performance and accessibility.

The GameCube’s Flipper GPU could handle advanced effects like real-time lighting, anti-aliasing, and texture filtering better than the PS2 in many cases. Although the Xbox GPU was more flexible and faster, Flipper allowed the GameCube to punch above its weight for its size and cost.

Nintendo undercut its rivals with a bold $199 price tag—an entire hundred dollars less than the PS2 and Xbox. On paper, this was a huge advantage. But the cheaper price wasn’t enough to tip the scales. Sony’s PlayStation 2 wasn’t just a console; it was also a DVD player, which made its higher cost more justifiable to parents and entertainment-hungry households. The GameCube, by contrast, was unapologetically a games-only device. For hardcore fans, that purity was charming. For the broader market, it was limiting.

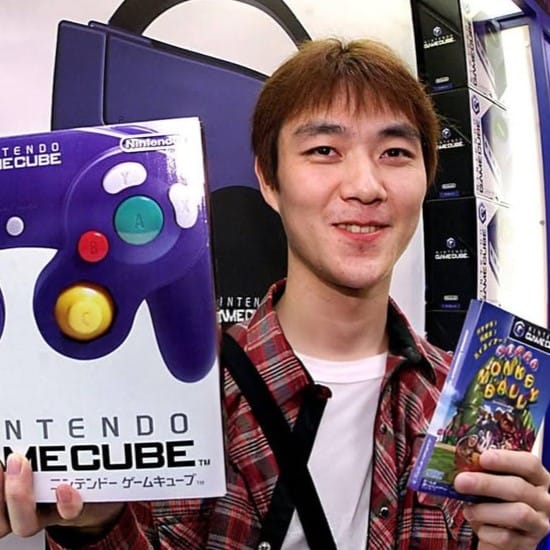

On paper, the GameCube came out swinging. It launched in North America on November 18, 2001, with a lineup that hit a surprising number of sweet spots. Super Smash Bros. Melee wasn’t just a sequel—it was a phenomenon, drawing in hardcore competitors and casual button-mashers alike. Star Wars Rogue Squadron II: Rogue Leader turned heads with its jaw-dropping visuals, showing off what the little purple box could really do. And Luigi’s Mansion, while unconventional, gave Mario’s oft-overlooked brother his first solo spotlight in a quirky, ghost-filled adventure

Perhaps the biggest shock at launch was who wasn’t there—Mario. For decades, Nintendo’s plumber had been the opening act for new hardware, from Super Mario World on the SNES to Super Mario 64 on the N64. But when the GameCube arrived, fans found no new Mario adventure waiting for them. Instead, Luigi took center stage with Luigi’s Mansion, while Nintendo banked on Wave Race: Blue Storm and Super Smash Bros. Melee to fill the gap. The lineup had quality, but it lacked the iconic punch that only a Mario game could deliver. It was a strange omission—and one that left the GameCube starting its race without its star runner.

Promising Beginnings, Unforgiving Market

On paper, the GameCube came out swinging. It launched in North America on November 18, 2001, with a lineup that hit a surprising number of sweet spots. Super Smash Bros. Melee wasn’t just a sequel—it was a phenomenon, drawing in hardcore competitors and casual button-mashers alike. Star Wars Rogue Squadron II: Rogue Leader turned heads with its jaw-dropping visuals, showing off what the little purple box could really do. And Luigi’s Mansion, while unconventional, gave Mario’s oft-overlooked brother his first solo spotlight in a quirky, ghost-filled adventure.

For a brief moment, the momentum was real. The GameCube was sleek, affordable, and undeniably fun. It didn’t try to be a DVD player or a media hub—it focused on games, plain and simple. And for early adopters, that purity had its charm.

But charm doesn’t win console wars.

As the months rolled on, that early luster began to fade. The PS2 had already established a juggernaut user base and enjoyed a growing avalanche of third-party support. Meanwhile, the GameCube’s library, though sprinkled with brilliance, struggled to maintain a consistent release cadence. Hype faded. Shelves grew sparse. The buzz quieted. The console wasn’t out of the fight—but it was already losing ground.

The PS2 Juggernaut: Too Big to Beat?

By the time the GameCube entered the ring, Sony’s PlayStation 2 was already steamrolling everything in its path. Released over a year earlier, the PS2 had momentum, marketing muscle, and perhaps its most cunning ace—DVD playback. In an era when standalone DVD players were still expensive luxuries, the PS2 offered households a slick, affordable way to dive into the digital movie age.

This wasn’t just about games anymore—it was about living room real estate. Parents saw value. Teens saw versatility. Sony had engineered a Trojan horse: a next-gen gaming console disguised as a home entertainment gateway.

Nintendo, in contrast, went minimalist. The GameCube focused solely on games. No DVD playback. No audio CD support. No frills. In theory, that focus should’ve been its strength. In practice, it made the console feel incomplete—like a toy in an age of multi-purpose machines.

The PlayStation 2 wasn’t just a game console; it was a Trojan horse into family living rooms. A sleek, modern DVD player that just so happened to play Ace Combat 4 and Final Fantasy X. It was the first console that parents bought just as eagerly as their kids. It slotted under TVs, next to surround sound systems, and into the center of domestic life.

The GameCube? It didn’t even try. No DVD playback. No music CDs. No online media functionality. It was games or nothing. Noble, maybe—but in a time when multifunctionality was becoming the gold standard, Nintendo’s laser-focus came off as tone-deaf.

While the PS2 became the nucleus of the living room, the GameCube stayed tucked away in bedrooms, dorms, and kids’ playrooms. It wasn’t seen as a household staple—it was seen as a toy. And toys, no matter how fun, rarely win format wars.

Tiny Discs, Big Problem: The Format That Backfired

At first glance, the GameCube’s mini-discs were endearing. Compact. Distinct. Almost futuristic in their novelty. But that cute 8cm design came with consequences—ones that would quietly chip away at the console’s long-term success.

Each disc held just 1.5GB of data. That might’ve worked for Nintendo’s tightly optimized first-party titles, but it was a headache for third-party developers accustomed to the sprawling freedom of the PlayStation 2’s 4.7GB DVDs. Suddenly, ambitious ports needed to be compressed, split across multiple discs, or outright scaled down. None of these were attractive options.

Studios didn’t want to spend extra resources retooling assets just to fit on Nintendo’s bespoke format. And in a time when cinematic cutscenes, voice acting, and high-fidelity visuals were rapidly evolving, the mini-disc became a bottleneck rather than a breakthrough.

Nintendo’s gamble on proprietary tech was nothing new, but this time, it came at a steep cost. In the race for content, developers didn’t want to fight the hardware. And with easier, larger, and more flexible options on the table, many simply walked away.

The ‘Kiddie’ Image Nintendo Couldn’t Shake

It didn’t matter how powerful the hardware was or how sharp the games looked—perception is everything. And the GameCube, for all its technical chops, looked like a toy straight off a department store shelf. Wrapped in indigo plastic with a handle on the back, it felt more Fisher-Price than future-tech.

First impressions stuck. Where the PS2 oozed sleek minimalism and the Xbox embraced a gritty, industrial edge, the GameCube practically screamed “safe for kids.” And in an era when gaming was rapidly aging up—Nintendo’s family-first image felt increasingly out of step.

It wasn’t just the hardware, either. The software lineup, while undeniably strong, leaned heavily into colorful, cartoonish aesthetics. Pikmin, Animal Crossing, Luigi’s Mansion—all delightful, but none of them shouted “edgy” to the 15-year-old crowd looking for blood, bass, and bravado.

Nintendo doubled down on charm when the market was craving attitude. And in the race for teen loyalty, that miscalculation left the GameCube sidelined—respected by fans, but dismissed by the cool crowd.

A Controller Ahead of Its Time (And That Weird Z Button)

The GameCube controller was a paradox—a marvel of ergonomic design wrapped in a layout that baffled more than a few developers. In your hands, it felt sublime. Contoured grips, a satisfyingly squishy analog stick, pressure-sensitive shoulder triggers—it was a controller that felt good to hold, even if you weren’t quite sure what all the buttons were doing.

For Super Smash Bros. Melee, it was amazing. The asymmetrical face buttons made sense in the context of a game built around them. Muscle memory kicked in fast. Precision was rewarded. No wonder it’s still the go-to for competitive Smash players more than two decades later.

But for multiplatform developers? It was a puzzle. The button shapes and sizes didn’t map easily to standard configurations on PS2 or Xbox. The tiny, stiff Z button perched awkwardly on the right shoulder. And where was the second Z? Or black and white buttons like Xbox had? Developers had to reimagine control schemes—or worse, cut corners to make things fit.

Nintendo had built a controller tailor-made for its own games. But in a generation where third-party support could make or break a system, that bespoke brilliance turned into a stumbling block.

Third-Party Support: History Repeats Itself

Old wounds from the N64 era didn’t heal overnight—and for Nintendo, they came back to haunt the GameCube. Developers remembered the cartridges. The high costs. The technical constraints. The creative compromises. So when the GameCube rolled onto the scene, many third-party giants approached with caution rather than enthusiasm.

Sure, there were moments of brilliance. Capcom delivered Viewtiful Joe, a GameCube exclusive that would later arrive on the PS2. Square dipped a toe back in with Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles, though the multiplayer setup was a logistical headache. EA brought the usual sports suspects, but the relationship felt more obligatory than passionate.

Across the board, the pattern was clear: ports came late, stripped-down, or not at all. The GameCube often got the B-team versions of multiplatform titles—missing content, downgraded visuals, or awkward controls thanks to that quirky button layout. Some major releases skipped the console entirely.

It wasn’t always about hardware. It was about trust. Sony and Microsoft were giving devs open arms and easy pipelines. Nintendo, with its guarded approach and proprietary quirks, still felt like a gated community. And when third parties looked at install base potential, they followed the numbers—straight to the PS2.

Online Gaming: A Generation Too Late

By the early 2000s, the internet wasn’t just a novelty—it was becoming a lifeline for competitive gamers. Broadband was spreading. Headsets were on. The future was wired. But while Xbox Live was redefining how people played and PlayStation 2 was at least trying to show up to the party, Nintendo stood stubbornly in the lobby, arms crossed.

The GameCube technically had online capability. There were adapters. There were a few games—Phantasy Star Online deserves a respectful nod. But support was minimal. Infrastructure was non-existent. Nintendo viewed online play as a niche rather than the next frontier, and that conservatism cost them.

Meanwhile, Xbox Live was fostering communities, rivalries, entire ecosystems. Kids weren’t just playing games—they were living inside them. Friends logged in nightly. Clan tags mattered. Rankings were gospel.

Nintendo, laser-focused on couch co-op and offline experiences, missed the signal flare. They treated online like an accessory, not a foundation. And in doing so, they let their competitors define the digital age of multiplayer—while the GameCube watched from the sidelines, modem unplugged.

Marketing Misfires and Mixed Messaging

When it came time to sell the GameCube, Nintendo brought a knife to a marketing gunfight. Where Sony draped the PlayStation 2 in coolness and cinematic swagger, and Microsoft flexed raw power and online bravado, Nintendo… got weird. Really weird.

There were purple cubes falling from the sky. There were abstract, artsy commercials that left more questions than answers. There were ads that tried to be edgy one minute, then pivoted to playground-friendly the next. It felt like watching a company argue with itself in public. Who was the GameCube for? Hardcore fans? Kids? Parents? The answer was never clear—and in a console war, that kind of brand identity crisis is fatal.

Despite having a technically powerful piece of hardware, Nintendo marketed the GameCube like it was a toy. The name didn’t help. The color scheme didn’t help. And the branding? A far cry from the sleek, futuristic vibes of the competition.

They were selling a heavyweight console with a featherweight voice. And in an era defined by style, swagger, and online ecosystems, the GameCube was caught whispering in a room full of shouty giants.

First-Party Powerhouses That Couldn’t Carry the Load

Nintendo’s first-party titles on the GameCube were nothing short of masterpieces. Metroid Prime redefined the first-person adventure genre, Pikmin introduced a charming and strategic new IP, and F-Zero GX delivered blistering speed with stunning visuals. These games were critically acclaimed and showcased Nintendo’s commitment to innovation and quality. However, despite their brilliance, they struggled to achieve mass-market appeal. For instance, while Metroid Prime was lauded for its design, it remained a niche title with limited commercial success, particularly outside of Japan.

The reliance on these niche titles highlighted a broader issue: Nintendo’s strategy leaned heavily on nostalgia and established franchises, often at the expense of developing new IPs that could capture a wider audience. While games like Pikmin were fresh and inventive, the market was shifting. Nostalgia was a warm blanket, sure, but the PS2 was offering new franchises, mature narratives, and constant innovation. Gran Turismo 3: A-Spec, Kingdom Hearts, Jak and Daxter, Ratchet & Clank—Sony’s lineup felt like the future.

This approach limited the GameCube’s appeal, especially among older gamers seeking more mature or diverse gaming experiences. Nintendo’s focus on its traditional strengths, while admirable, wasn’t enough to counteract the broader market trends favoring more expansive and varied game libraries.

Game Boy Advance Connectivity: A Cool Idea That Nobody Used

On paper, it sounded revolutionary. Connect your Game Boy Advance to the GameCube and unlock new experiences. Hidden items, bonus content, even entire modes. It was Nintendo doing what Nintendo does—chasing the peculiar, the bespoke, the “only on our hardware” kind of magic.

But there was a catch. A big one. Actually, four of them.

Zelda: Four Swords Adventures required not just a copy of the game, but four GBAs and four link cables. It was a logistical nightmare disguised as a multiplayer experiment. Unless you had three equally obsessed friends and a tangled mess of wires, that ambitious vision stayed firmly in the realm of theory.

Other titles like Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles leaned on the same tech, but the barrier to entry remained ludicrously high. It wasn’t plug-and-play—it was plug-and-pray.

The idea wasn’t inherently flawed. It just needed more accessibility, more support, and more killer apps. Instead, it became a footnote. A conversation piece. Innovation without traction. Cool, sure—but utterly impractical for the average living room.

Region Locking and Import Frustrations

While Sony and Microsoft were easing up on borders, Nintendo doubled down. The GameCube’s hardware came wrapped in a digital straightjacket—region locking that made import gaming a chore, if not an outright impossibility. For global enthusiasts, it was maddening.

Japan got the cooler box art. Europe got exclusive bundles. North America missed out on niche RPGs and offbeat oddities that never left Japanese shores. Want to play Dōbutsu no Mori e+ or Giftpia? Tough luck—unless you had an Action Replay, a boot disc, or a modded console and a prayer.

This wasn’t just about language barriers. It was about choice. Freedom. A missed opportunity to nurture the hardcore crowd that lived for obscure titles and quirky imports. The kind of fans who evangelize consoles for decades afterward.

Instead, Nintendo walled them out. While the PlayStation 2 quietly opened doors, the GameCube locked them, bolted them, and threw away the key. A frustrating decision in a generation defined by access and appetite.

The Rise of Xbox: A New Challenger Appears

Just as Nintendo was trying to recover from Sony’s one-two punch, another giant kicked down the door. Microsoft entered the ring in 2001 like a tech titan with something to prove—and $500 million in marketing muscle to prove it. The original Xbox wasn’t just powerful—it was bold, brash, and unapologetically American.

Suddenly, the console war had three fronts.

Sony had the mainstream. Microsoft was gunning for the hardcore. And Nintendo? Nintendo was caught in the middle—outgunned, outspent, and struggling to find its audience.

The Xbox didn’t need to beat the GameCube head-on; it just needed to fracture the market enough to squeeze it out of relevance. Teenagers chasing online frag-fests weren’t lining up for Super Monkey Ball. Nintendo’s whimsical charm felt quaint in a world of LAN parties and Mountain Dew-fueled shootouts.

And so, the GameCube found itself boxed in—no longer just the underdog to Sony, but the odd one out in a rapidly evolving landscape.

The Numbers Game: Solid Sales, But Not Enough

In raw numbers, the GameCube didn’t flop. With over 21 million units sold worldwide, it comfortably outpaced the Sega Dreamcast. It even inched ahead of the original Xbox in Japan, where Microsoft’s big black box barely made a dent. But context is everything.

The PS2, by comparison, soared to an astronomical 160 million units. It wasn’t just a best-seller—it was a cultural mainstay. Even when stacked against Nintendo’s own history, the story felt underwhelming. The N64 moved nearly 33 million units, and while that console had its own third-party woes, it still commanded more visibility and retained greater cachet among older gamers.

So yes—GameCube sold. But it didn’t soar. It survived. It hustled. And for a company that once defined the very idea of video gaming dominance, simply staying afloat wasn’t the win it needed. Not in a generation where the bar was sky-high and climbing.

Cult Classic Status: Why Fans Still Swear by It

The GameCube didn’t win its generation—but it won hearts. Millions of them. Loud, loyal, and still hooked two decades later.

Because here’s the thing: while the mainstream marched to the beat of DVDs and edgy shooters, the GameCube was quietly assembling a legacy of its own. That iconic controller, with its asymmetrical button layout and satisfyingly springy triggers? A tactile love letter that still fuels Smash Bros. tournaments to this day. Ask any veteran player—there’s no substitute.

Then there were the exclusives. Not just good games. Legendary ones. Metroid Prime. Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door. Eternal Darkness. Tales of Symphonia. F-Zero GX. Nintendo’s purple cube didn’t scream for attention—it curated. Carefully. Quirkily. Lovingly.

And while the GameCube’s commercial scars were once easy to spot, time has a way of reframing failure. What once looked like a misfire now feels like a misunderstood masterpiece. Nostalgia softened the sharp edges. Fan passion filled in the gaps. Today, the GameCube sits on the shelf not as a cautionary tale, but as a cult icon—a reminder that being different isn’t always a mistake. Sometimes, it’s the reason people remember you at all.

Was It Really a Failure? Rethinking Success in Hindsight

Failure is a strange word in the gaming world. Sometimes it means low sales. Sometimes it means poor reviews. And sometimes, like in the case of the GameCube, it simply means not being the biggest name in the room.

On paper, sure—Nintendo’s cube-shaped contender was outgunned, outpaced, and overshadowed. It didn’t dominate the living room like the PS2. It didn’t spark a revolution like the Xbox’s online push. It didn’t even outsell its predecessor, the N64. But here’s the twist: people love the GameCube. Deeply. Obsessively. And not just with rose-tinted glasses, but with full-blown, badge-wearing pride.

Its sales might’ve been modest, but its legacy? Immaculate. It’s the console that gave us Metroid Prime. That kept Smash Bros. at house party royalty levels. That nurtured weird, wonderful experiments like Eternal Darkness and Chibi-Robo. It became a rite of passage for collectors, a fixture in dorm rooms, a mainstay in retro rankings.

The GameCube didn’t win the console war. But it survived the battle for relevance. And two decades later, that might matter more.

Because when the dust settles, what we remember isn’t the sales charts—it’s the memories. And on that front, the GameCube is still punching above its weight.