The year was 1999. Y2K paranoia gripped the world, The Matrix redefined cinema, and the gaming industry stood on the brink of a technological revolution. At the heart of this digital shake-up was the Tokyo Game Show 1999, where the past, present, and future of gaming collided in an explosion of innovation and hype.

The air inside the Makuhari Messe was thick with possibility—gamers, press, and industry titans all packed shoulder to shoulder, eager to witness what would shape the next era of interactive entertainment. Sega, still reeling from past missteps, pushed the Dreamcast with a fiery determination. Sony, playing the long game, dropped cryptic hints about the PlayStation 2, a machine that would eventually dominate the decade.

It was a time of boundless ambition, where every trailer, every reveal, and every whisper of new hardware sent shockwaves through the industry. Tokyo Game Show 1999 wasn’t just another expo—it was a turning point. A glimpse into gaming’s bold, uncertain future.

The Show Floor Spectacle: A Gamer’s Paradise

The moment you stepped onto the show floor, it hit you—a symphony of sights, sounds, and sheer spectacle. The air buzzed with excitement, a cacophony of game trailers blaring from oversized CRT screens, the rhythmic thumping of arcade cabinets in the distance, and the collective murmur of thousands of attendees, each one eager to get their hands on the next big thing. Tokyo Game Show 1999 wasn’t just an industry event—it was an extravaganza, a digital wonderland where gaming’s future unfolded in real time.

Sega didn’t just show up to Tokyo Game Show 1999—they arrived with something to prove. The Dreamcast was their boldest, most audacious gamble yet, a machine that pulsed with raw power, arcade-perfect visuals, and an online future that felt like science fiction. For Sega, this wasn’t just about selling a console. This was survival.

Their booth was a fortress of confidence, drenched in electric blue light and packed wall-to-wall with software designed to silence doubters. Shenmue, with its living, breathing world, was the crown jewel. Attendees stood mesmerized, watching Ryo Hazuki explore Dobuita with an uncanny level of realism, interacting with NPCs who seemed to have minds of their own. No one had ever seen anything like it. But Sega had more than just one trick up its sleeve.

Crazy Taxi screamed into the show, delivering pure arcade chaos as players weaved through traffic, launching their cabs off ramps with reckless abandon. Jet Set Radio turned heads with its cel-shaded graffiti aesthetic, a style so fresh it looked ripped from the future. Phantasy Star Online, barely more than a whisper at this stage, hinted at an online revolution no one was ready for. And then there was Soulcalibur—a visceral, hyper-fluid fighter that looked so sharp, so impossibly smooth, that it made the PlayStation’s best efforts feel almost ancient.

But even as Sega flexed its creative muscle, a question loomed: Was this their last stand? The PlayStation had transformed Sony into a gaming juggernaut, and with the PlayStation 2 looming on the horizon, the industry was already shifting. Despite the Dreamcast’s head start and technical prowess, whispers of the PS2’s hardware capabilities stirred unease. Would Sega’s do-or-die bet pay off, or was this simply a dazzling, defiant last act?

For now, none of that mattered. On the show floor, in the heat of the moment, the Dreamcast was king. And for a fleeting instant, it felt like Sega could win it all.

Not to be outdone, Sony exuded quiet confidence. While the PlayStation 2 loomed just beyond the horizon, their focus remained on the PlayStation’s unstoppable software lineup. The booth was a feast of genre-defining titles—Final Fantasy VIII drew enormous lines, and Gran Turismo 2’s ultra-polished racing sim credentials turned heads. Sony didn’t need to shout. Their dominance was self-evident.

Everywhere you turned, something demanded your attention—arcade-perfect ports, experimental tech demos, and developers showing off their most ambitious ideas. Tokyo Game Show 1999 wasn’t just a sneak peek into the future of gaming. It was a declaration that the medium was evolving—faster, bolder, and more electrifying than ever before.

While Sega and Sony fought for dominance under the neon glow of Tokyo Game Show 1999, one giant was conspicuously absent: Nintendo. No sprawling booths. No developer panels. No bombshell reveals. It wasn’t a scheduling conflict. It was a choice. And one that left the gaming world buzzing with speculation. Was Nintendo playing it safe—or playing the long game?

At a time when PlayStation was revolutionizing home consoles and Sega was doubling down on the Dreamcast, Nintendo’s silence felt almost defiant. The company had skipped TGS before, preferring to march to the beat of its own drum, but this time, the stakes were different. With the Nintendo 64 struggling against Sony’s juggernaut and whispers of the “Dolphin” (the codename for what would become the GameCube) floating through industry circles, their absence left a void—and a lot of unanswered questions.

But make no mistake—Nintendo wasn’t retreating. They were dominating a different battlefield. While the console wars raged, Pokémon was an unstoppable force. Pokémon Red and Blue had exploded worldwide, Pokémon Yellow was breaking records, and the anime was a cultural phenomenon. The Game Boy, once seen as a relic of the late ‘80s, had become an empire unto itself, fueled by pocket monsters and link-cable battles in every schoolyard from Tokyo to New York.

Nintendo didn’t need a flashy stage at TGS 1999. They already owned the minds of millions—kids, teenagers, even parents. While Sega was betting the house on the Dreamcast and Sony was teasing the PlayStation 2, Nintendo was busy printing money in the form of Poké Balls.

Still, their absence at TGS sent a message. To some, it signaled confidence—a refusal to play by industry rules. To others, it felt like a missed opportunity, a moment where Nintendo could have reminded the world that they weren’t just the company of Mario and Pikachu—they were pioneers, innovators, disruptors.

Had Nintendo made a brilliant strategic move or a costly misstep? The answer wouldn’t be clear until years later. But at that moment, with PlayStation ascendant and Sega fighting for survival, one thing was certain—the gaming landscape was shifting, and Nintendo was playing a different game entirely.

Fighting Game Fever

By 1999, fighting games weren’t just a genre—they were a cultural battleground. Arcades were still alive with the crackle of joystick clicks and the rhythmic tapping of buttons, but home consoles were catching up, delivering competitive experiences without the need for a pocketful of 100-yen coins. At Tokyo Game Show 1999, this divide was on full display, with Capcom, Namco, and SNK each vying for dominance in a scene that was as fierce as the matchups themselves.

On the arcade side, nothing commanded more reverence than Street Fighter III: 3rd Strike. Capcom’s hand-animated masterpiece was a technical tour de force, boasting fluid animation, frame-perfect parries, and a skill ceiling so high it bordered on legendary. Fans gathered around kiosks to witness high-level play, with some already whispering about strategies and tactics that would later be immortalized in EVO highlight reels. The game had arcade purists in a chokehold, proving that 2D fighters weren’t just alive—they were evolving.

But while Capcom remained loyal to the arcade scene, the writing was on the wall. Console ports were improving, and the rise of online gaming was lurking just over the horizon. Would arcades survive the coming decade? That was the unspoken question as crowds surrounded the 3rd Strike booths, absorbing every frame of pixel-perfect combat.

Meanwhile, Namco was playing a different game. Tekken Tag Tournament was a showstopper, pushing the PlayStation 2’s hardware to its limits—even before the console had officially launched. The game’s tag mechanics, gorgeous character models, and buttery-smooth animations made it clear: 3D fighters weren’t just catching up to 2D—they were stealing the spotlight.

Tekken’s presence at TGS 1999 was more than just hype—it was a statement of intent. Namco was leading the charge for 3D fighters, setting the stage for an era where arcade cabinets would have to battle against home console perfection. With Dead or Alive 2 and Virtua Fighter 4 looming on the horizon, the genre was at a crossroads. Would the next generation belong to the arcade, or was the future of fighting games already moving to the living room?

While Capcom and Namco battled for supremacy, SNK was fighting for survival. At TGS 1999, The King of Fighters ‘99 was SNK’s love letter to arcade loyalists, proving that sprite-based combat still had plenty of fight left. Featuring new characters, a striker system, and a darker storyline, KOF ‘99 showcased everything that made SNK’s fighters special—fast, technical gameplay with an unrivaled sense of style.

But behind the scenes, SNK was in trouble. The company’s financial struggles were well-documented, and while fans still packed the booths to play the latest KOF entry, there was an air of uncertainty. Could SNK keep up with the industry’s shift to 3D? Would their devotion to hand-drawn, frame-by-frame animation be their salvation—or their downfall?

TGS 1999 was a turning point for the fighting game scene. The battle between arcades and consoles was heating up, and while games like 3rd Strike and KOF ‘99 proved that 2D fighters still had a place, titles like Tekken Tag Tournament hinted at a future where arcade halls might not be the genre’s proving ground anymore. The question wasn’t if fighting games would survive—it was which version of them would dominate the next era.

Music and Rhythm Games

By 1999, something new and electrifying was taking over Japan’s arcades. It wasn’t about combos, fatalities, or speed runs—it was about rhythm. Tokyo Game Show 1999 was a pulsating showcase of the music game explosion, a moment where beats and flashing arrows became just as thrilling as a perfectly executed dragon punch.

Konami had struck gold with Beatmania, a game that turned ordinary players into turntable virtuosos. With its five-button setup and a turntable controller, the game let players scratch, mix, and tap their way to musical mastery. At TGS 1999, Beatmania was everywhere—booths packed with fans watching competitors hammer out complex note patterns with pinpoint accuracy. The game’s impact was immediate and undeniable.

More than just a game, Beatmania was a cultural phenomenon, laying the foundation for what would become Bemani, Konami’s entire division dedicated to rhythm-based titles. This was the seed that would eventually grow into pop juggernauts like DJMax, Sound Voltex, and even Guitar Hero years later.

But if Beatmania captivated the ears, Dance Dance Revolution took over the entire body. With its glowing dance pad and heart-pounding tracks, DDR was the game that turned arcades into nightclubs. At TGS 1999, Konami showcased DDR 2nd Mix, and the energy was off the charts. Crowds gathered around, mesmerized by players who could spin, stomp, and shuffle at inhuman speeds.

DDR was more than a game; it was a test of endurance, style, and rhythm. Players didn’t just win—they performed. At a time when home consoles were starting to erode arcade dominance, DDR gave players a reason to step out of their homes and into the neon-lit arenas of gaming centers.

The success of Beatmania and DDR wasn’t a fluke—it was a seismic shift in gaming culture. These games proved that you didn’t need a controller full of buttons to feel powerful. Whether you were scratching vinyl or dancing your heart out, rhythm games created an entirely new way to play.

And this was just the beginning. The music game craze was about to expand, invading home consoles with future hits like Parappa the Rapper, Bust a Groove, and eventually, the Guitar Hero and Rock Band phenomena of the 2000s. What started as an arcade experiment had sparked a revolution—one that still echoes through gaming history today.

Hidden Gems of TGS 1999

For every blockbuster that commanded center stage at Tokyo Game Show 1999, there were a dozen oddball curiosities lurking in the corners of the show floor. These were the games that made attendees pause—not because of cutting-edge graphics or franchise pedigree, but because they were just plain bizarre. Some were experimental, others wildly ambitious, and a few were so uniquely Japanese that they never left the country. But all of them embodied the kind of fearless creativity that made late-’90s gaming so special.

Nestled between the heavy hitters were games that dared to be different. One such oddity was L.O.L.: Lack of Love, a hauntingly beautiful adventure from ASCII Entertainment. This dialogue-free, evolution-based game put players in control of an alien lifeform, forcing them to adapt, survive, and evolve in a strange and hostile world. It was part game, part existential meditation—a perfect example of the era’s artistic risks that would later inspire cult classics like Shadow of the Colossus and Journey.

Then there was Boku no Natsuyasumi, a charming slice-of-life adventure from Millennium Kitchen. While the show floor was dominated by high-octane action and futuristic spectacle, this game embraced the quiet nostalgia of a Japanese summer vacation. Players took on the role of a young boy exploring the countryside, catching bugs, and making memories—a slow, reflective experience that would go on to pioneer the “wholesome gaming” genre.

Not every game at TGS 1999 was destined for worldwide fame. Some were too niche, too eccentric, or just too uniquely Japanese to ever see an international release. One such title was Tokyo Bus Guide, a hyper-detailed bus-driving simulation that turned precision parking and following traffic laws into an almost meditative challenge. It was an instant hit with Japanese gamers, proving that even the most mundane concepts could become engrossing when executed with love and detail.

And then there was Segagaga, a game that could have only come from Sega’s wonderfully unhinged imagination. This Dreamcast RPG cast players as the new CEO of Sega, tasked with saving the company from a fictionalized, all-powerful rival (which, let’s be honest, was a barely disguised PlayStation). Packed with self-deprecating humor, surreal cutscenes, and cameos from classic Sega characters, it was a love letter and a last hurrah—one that never left Japan, making it one of the Dreamcast’s most fascinating lost treasures.

TGS 1999 wasn’t just about the biggest names or the best graphics. It was also about the games that took risks, the ones that made people stop and say, What did I just play? In an era where the industry wasn’t afraid to experiment, these hidden gems proved that gaming’s most interesting moments often come from the strangest places.

Hardware Highlights

Tokyo Game Show 1999 wasn’t just about the games. It was a tech lover’s paradise, where manufacturers unveiled the wildest, weirdest, and most forward-thinking peripherals designed to enhance the gaming experience. Some of these innovations would become industry staples, while others faded into obscurity—but for that weekend in 1999, they were all the talk of the show floor.

The DualShock was already revolutionizing gaming, but that didn’t stop third-party developers from throwing their own spin on the formula. Everywhere you looked, booths showcased controllers with extra buttons, bizarre shapes, and features no one asked for but somehow wanted to try. Hori had their usual lineup of high-quality arcade sticks, catering to the booming fighting game scene, while ASCII pushed keyboard hybrids that blurred the line between console and PC gaming.

Then there was the Sega Dreamcast Fishing Controller—a peripheral so oddly specific that it became an instant cult favorite. Designed for Sega Bass Fishing, it featured a motion-sensitive reel that let players physically cast and retrieve their line. It was goofy, unnecessary, and absolutely remarkable.

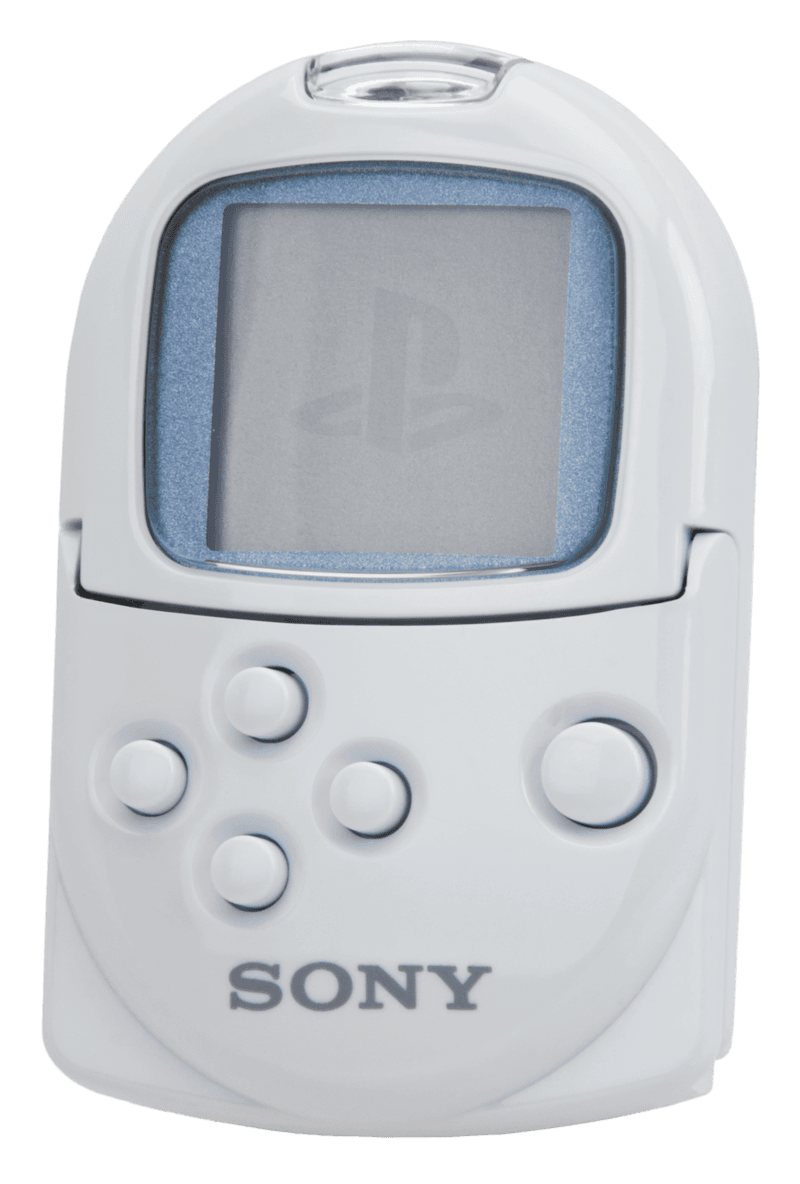

TGS 1999 also hinted at the future in ways most gamers didn’t fully grasp at the time. Sony’s PocketStation—a tiny memory card with an LCD screen—was everywhere, offering mini-games, save data management, and even early connectivity features for select PlayStation titles. Though it never officially launched outside Japan, it set the stage for later handheld-integrated gaming like the GameCube-to-GBA link and the PSP’s Remote Play.

Meanwhile, mobile gaming was beginning to stir. Bandai was showing off the WonderSwan, a sleek handheld designed by Game Boy creator Gunpei Yokoi. With its sharp monochrome screen, impressive battery life, and unique vertical-horizontal play modes, it was a serious challenger in the handheld space. While it never dethroned Nintendo, it cemented itself as a beloved alternative, especially for RPG fans who flocked to its exclusive Square Enix support.

Tokyo Game Show 1999 wasn’t just about what was playable right then—it was a preview of where gaming was heading. Whether it was through quirky peripherals, handheld evolution, or the first steps toward interconnected gaming, the hardware innovations of that year planted the seeds for the gaming landscape we know today.

Legacy of Tokyo Game Show 1999

A quarter-century later, the echoes of Tokyo Game Show 1999 still reverberate through the industry. What felt like a fleeting moment of spectacle at the time was, in hindsight, a pivotal crossroads—one where the gaming landscape braced for a seismic shift. The titles, the hardware, the trends—it was all a preview of where gaming was headed, even if few realized it at the time.

Looking back, TGS 1999 was Sony’s silent flex. When the PlayStation 2 finally launched in 2000, its success felt inevitable. The seeds had been planted at TGS ‘99, through strategic teases, developer confidence, and an industry that was already shifting in Sony’s favor. Sega’s Dreamcast, despite its dazzling presence, couldn’t withstand the momentum. Nintendo, absent from the show, had yet to prove it could keep pace. The PS2 era wasn’t just beginning—it had already been written.

It was a show of transition, a bridge between the late ‘90s and the dawn of the new millennium. And even now, 25 years later, its legacy can still be felt—in the franchises that continue, in the genres that evolved, and in the way gaming became the unstoppable force it is today.