It’s almost absurd in hindsight. That the company behind Microsoft Office—staples of spreadsheets, pie charts, and painfully dry corporate demos—would dare to elbow its way into the console wars at the dawn of the 21st century. A gaming console, from Microsoft? Industry veterans scoffed. Journalists rolled their eyes. The cool kids already had their PS2s. Bill Gates had no business talking about video games, let alone launching a black monolith with a glowing green eye that promised to “change everything.” And yet, that’s exactly what happened.

The original Xbox wasn’t just another plastic box—it was a Frankenstein machine of PC internals, Ethernet ambition, and bold software dreams. It was too big, too heavy, and too expensive to make sense. But it also had something no other console had: raw power and an unapologetically PC soul. This is the story of how one of the most unexpected hardware launches in gaming history flipped the script—and proved that even a boring corporate goliath could reinvent itself with the right silicon and game library.

From Office Software to Living Room Hardware

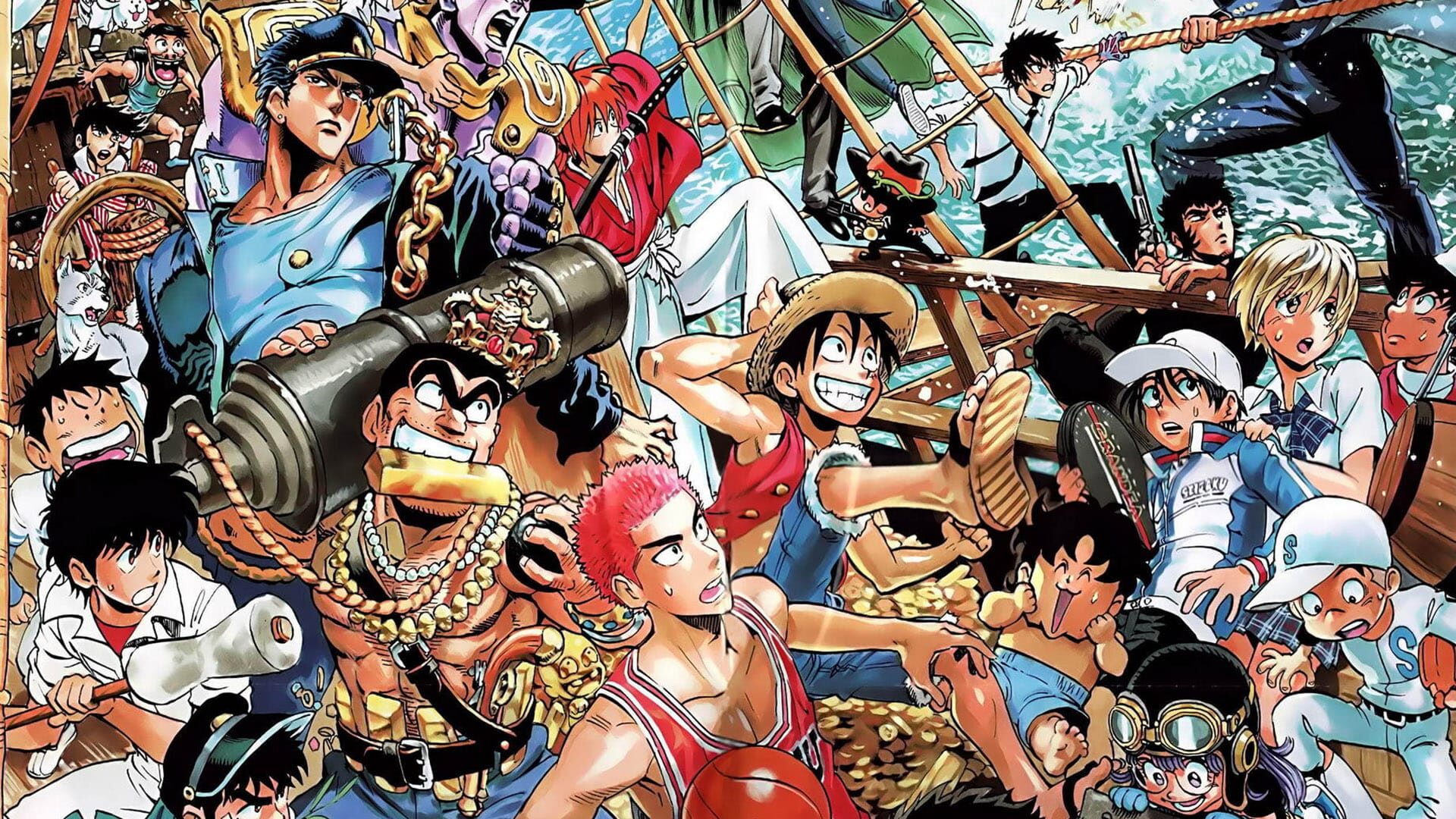

By the turn of the millennium, home consoles weren’t just dominated by Japanese companies—they were defined by them. Nintendo had built the modern gaming industry on the back of the NES, Sega had pushed the boundaries of arcade-style action at home, and Sony’s PlayStation had reimagined gaming as sleek, cinematic entertainment. Their machines weren’t just products; they were cultural icons. Each generation reinforced the same truth: if you wanted to compete in the console space, you had to speak the language of Kyoto and Tokyo.

Let’s be honest—Western console history before Xbox was… rough. Atari’s once-mighty brand collapsed under the weight of rushed hardware and dwindling third-party support. The 3DO promised cutting-edge technology and a revolutionary licensing model, but its astronomical launch price alienated consumers before it could gain traction. Each failure reinforced the industry’s unspoken law: hardware from the West was either underpowered, overpriced, or under-supported.

When Sony unveiled the PlayStation 2 in 1999, it wasn’t just pitching a new console—it was introducing a cultural phenomenon. Sleek, jet-black, and futuristic, the PS2 promised more than cutting-edge 3D graphics. It played DVDs at a time when standalone players cost hundreds of dollars, it doubled as a music hub, and it hinted at a future where your console might also connect you to the internet. The PS2 wasn’t a toy—it was a lifestyle accessory. By the time it hit shelves, the hype was so intense that owning one felt less like buying a console and more like buying a ticket to the future. No one expected a Silicon Valley—or Redmond—upstart to challenge Japan’s iron grip on living room gaming. No one, except Microsoft.

What began as murmurs inside Redmond conference rooms quickly morphed into code-red urgency. Gates and his top brass knew they had to act fast. They had to beat Sony at its own game—not with gimmicks, but with brute-force vision. The solution? Think like a gamer, build like a PC enthusiast, and weaponize the one thing Microsoft understood better than anyone else: software.

For Microsoft, this was more than a competitor—Bill Gates and his executives saw the PS2 as an existential threat. Bill Gates was not about to let that happen. The answer wasn’t to dismiss the PS2 as a fad—it was to fight fire with fire. Microsoft needed a machine that could go toe-to-toe with Sony’s hardware, beat it in raw power, and match or exceed its multimedia potential. But more importantly, it needed to be a platform—a controlled ecosystem that could tie developers and players into Microsoft’s vision for the future.

The DirectX Dream Team

Seamus Blackley, Kevin Bachus, Otto Berkes, and Ted Hase weren’t hardware visionaries in the traditional sense, but they could see the writing on the wall. If Sony could position the PlayStation as the centerpiece of home entertainment—handling games, movies, music, and maybe even light computing—then suddenly the Windows PC would no longer be the undisputed hub of the household. That kind of encroachment could chip away at Microsoft’s dominance in ways no rival had managed before.

So they pitched something unthinkable: let’s take DirectX, the bedrock of PC gaming, and build a console around it. Not some Frankenstein prototype. A real console. Sleek. Scalable. Developer-friendly. It would run with the muscle of a gaming rig and the accessibility of a plug-and-play machine.

March 30, 1999. Ted Hase sent out a PowerPoint presentation that would kick off one of the most ambitious hardware projects in Microsoft’s history. The slides weren’t flashy, but the vision was bold: a console that could leverage Microsoft’s strengths—PC hardware knowledge, DirectX software expertise, and a robust developer ecosystem—and challenge Sony head-on.

The timing was no accident. The PlayStation 2 announcement had rattled Redmond. Hase’s pitch wasn’t just about games—it was about defending Microsoft’s turf in the home. The presentation made its way to the right inboxes, and soon the idea had legs. The next step? Sell it to the people who could actually greenlight it.

When Hase, Blackley, Bachus, and Berkes finally pitched their vision in person, the room’s reaction wasn’t exactly a standing ovation. As Kevin Bachus later recalled, “Everyone started laughing.” Not dismissively, but with the kind of disbelief that comes when someone proposes something wildly out of character.

Microsoft was a software titan, the company behind Office and Windows—not Nintendo or Sega. The idea of them building a console seemed absurd. Still, the proposal was intriguing enough to survive the initial wave of doubt. “This isn’t what we’d intended to discuss,” one exec admitted, “but it’s an interesting idea. Let’s follow up on that.”

That seed of interest was all it needed. What began as an improbable side project in the shadows of Redmond would soon snowball into a billion-dollar gamble—one that would change gaming history.

Internally, it was called the “DirectX Box.” Kind of a mouthful. Kinda brilliant. Eventually, that clunky code name was trimmed down—first to “Xbox,” then quickly slapped onto every whiteboard, hallway wall, and whispered meeting agenda in the building. The suits hated it. Marketing flinched. But the name stuck. It felt dangerous. New. Different.

The DirectX team hadn’t just engineered a machine—they’d ignited a movement. One that would drag the console world, kicking and screaming, into the era of high-performance, internet-connected, PC-minded gaming.

The World’s Worst Kept Secret – GDC 2000

March 2000. Game Developers Conference. The crowd already knew something was brewing—Microsoft’s “mystery” project had been leaking like a sieve for months. Then, in strolls Bill Gates, rocking his trademark dad-sweater confidence, ready to officially pull back the curtain. This was it: the Xbox. Microsoft’s first swing at a dedicated gaming console, and their not-so-subtle declaration that they were coming for Sony’s lunch money. The room didn’t just see another plastic box; they saw a tech giant throwing down in an arena they’d never fought in before.

| Specifications | Microsoft Xbox | Sony PlayStation 2 | Nintendo GameCube |

| CPU | Intel Pentium III, 733 MHz | “Emotion Engine” MIPS R5900, 294 MHz | IBM “Gekko” PowerPC, 485 MHz |

| GPU | Nvidia NV2a, 250 MHz | Graphics Synthesizer, 147 MHz | ATI “Flipper”, 162 MHz |

| RAM | 64 MB DDR SDRAM (unified) | 32 MB RDRAM | 24 MB 1T-SRAM + 16 MB DRAM |

| Storage | 8 GB internal hard drive | Memory cards only | Memory cards only |

| Optical Media | DVD-ROM | DVD-ROM | Mini-DVD (1.5 GB) |

| Disc Playback | DVD movies (remote required) | DVD movies (out of the box) | None (games only) |

| Video Output | Up to 480p | Up to 480i | Up to 480p |

| Online Capability | Built-in broadband Ethernet | Network adapter (sold separately) | Broadband/Modem adapter (sold separately) |

| Controller | “Duke” (later Controller S) | DualShock 2 | GameCube Controller |

| Launch Price (US) | $299 | $299 | $199 |

On paper, the thing was a beast for its time. The Intel Pentium III CPU alone made the PlayStation 2’s “Emotion Engine” look underfed, and the Nvidia NV2a GPU could push visuals that were shockingly close to high-end PC games of the day. Then there was the hard drive—an absolute game-changer. While PS2 and GameCube owners were juggling stacks of memory cards, Xbox players could save dozens of games, store custom soundtracks, and load content faster without touching extra accessories. Add built-in broadband Ethernet, and suddenly online play wasn’t some optional afterthought—it was part of the DNA.

It was broadband-ready straight out of the box, at a time when your buddy down the street was still hearing the dial-up modem sing its sad little song. You could download updates. Store entire game soundtracks. Rip your own Linkin Park CDs (or whatever you were into back then, I won’t judge) and use them as custom in-game music for Project Gotham Racing. It transformed the Xbox into something… more.

Sure, the GameCube had Nintendo’s first-party magic and the PS2 had a killer head start in sales, but raw power? That was all Xbox. It wasn’t playing in the same league as its rivals; it was showing up to a knife fight with a high-powered rifle. It felt revolutionary—because it was.

Of course, Gates was quick to insist that the Xbox wasn’t simply a Windows machine in disguise. Sure, it ran on a streamlined Windows 2000 kernel, but Microsoft drew the line at letting you plug in a regular keyboard and mouse. They wanted console gamers to feel at home, not like they were sitting down to do their taxes. Still, under the hood, it was hard to ignore the PC blood pumping through its oversized veins.

Selling the Idea: Marketing the Xbox to Skeptical Gamers

So, you’ve got a machine the size of a VCR on steroids. Now what? That was Microsoft’s next hurdle: making it cool. Because let’s be honest—gamers weren’t exactly begging for a console from the company that brought them Clippy. And while the Xbox had the power, it still needed swagger. So Microsoft went loud. Brash. Aggressively Gen-X.

They leaned into the box’s aesthetic with confidence. That radioactive-green logo? It wasn’t subtle. It looked like a sci-fi warning sign slapped onto a black ops briefcase. And the branding oozed early-2000s attitude. Ads pulsed with distorted metal riffs, glitchy editing, and Mountain Dew-soaked energy. This wasn’t for your kid brother. This was for you—the LAN-party veteran, the FPS purist, the thrill-seeking joystick junkie.

Then there was the controller. Ah, the “Duke.” Microsoft’s original gamepad was… divisive. Massive, bulbous, and unlike anything else on the market, it fit hands the way a steering wheel fits a Vespa. For smaller players, it was an ergonomic nightmare. But for those who embraced it? It was a weapon. A beast. A bold counterpunch to the dainty DualShock. Love it or hate it, the Duke was unforgettable.

Microsoft was marketing on a scale console gaming had never seen before. TV spots, magazine spreads, giant billboards, sponsorships—you name it, Xbox was on it. The campaign wasn’t subtle either. It leaned hard into the console’s power and its online capabilities. If you were a gamer in 2001, you couldn’t go a week without seeing that glowing green X burning into your retinas. The message was clear: this wasn’t some quirky side project—Microsoft was here to play for keeps.

And that was the point. The Xbox wasn’t here to play nice. It wasn’t chasing the mass market—not yet. Instead, it zeroed in on the hardcore. Shooters. Sports. Online play. The games that demanded precision, grit, and immersion. If the PlayStation was pop culture, Xbox wanted to be counterculture.

Of course, flashy ads only get you so far if your console doesn’t have the games to back it up. Microsoft knew third-party support was the lifeblood of any successful system, so they went on a charm offensive worthy of a dating reality show. Studios were lured in with powerful, PC-like hardware that cut down on development headaches, robust DirectX tools, and the promise of a massive U.S. marketing push for their titles. Add generous publishing deals and competitive royalty rates, and suddenly developers who’d been loyal to Sony or Nintendo were giving the big green X a serious second look. For many, the Xbox wasn’t just a new platform—it was a fresh start.

Microsoft didn’t need to win everyone—just the right ones. The loud ones. The passionate ones. The early adopters who’d turn their living rooms into battlestations and evangelize the Xbox like it was the second coming of LAN.

Launching a Revolution: The Xbox Hits the Market

November 15, 2001. The day Microsoft stopped being just a software titan—and kicked in the doors of the console wars. The original Xbox finally landed, wrapped in midnight plastic, glowing with that unmistakable radioactive green. On paper, it was a beast. In stores? It was a curiosity. Retailers weren’t sure what to make of it. Gamers were skeptical. And competitors—especially Sony—were watching with popcorn in hand, expecting a glorious, billion-dollar belly flop.

And at first? It kinda looked like one.

If Microsoft was nervous about competing with Sony’s head start, the numbers calmed those fears fast. By the end of 2001, just a month and a half after launch, over 1.5 million Xbox consoles had found their way into living rooms across America. Even better? Buyers weren’t just grabbing the machine—they were scooping up games at an average of three per console. For a rookie in the console business, those figures weren’t just solid—they were a statement. Microsoft had landed, and they weren’t going anywhere.

February 22, 2002. Microsoft knew Japan wasn’t going to welcome the Xbox with open arms. To sweeten the deal, they launched the system with 12 titles tailored specifically for Japanese gamers and redesigned the bulky “Duke” controller into a smaller, more manageable version. It was a clear message: they weren’t just shipping a Western console and hoping for the best—they were trying to adapt to local tastes.

To drum up excitement, Microsoft released 50,000 special edition Xbox units exclusively for Japan. Shiny, limited, and collector-friendly, these consoles were supposed to create buzz and drive early adoption. But despite the fanfare, the special editions couldn’t overcome the deeper challenge: Japanese gamers were still skeptical of a foreign console entering a market steeped in decades of local loyalty.

If there was a speed bump big enough to scare even the boldest executive, it was the disc scratching controversy. Reports of scratched game discs and DVDs spread quickly, forcing some retailers to temporarily halt sales. For a console trying to prove itself in a tough market, it was a PR nightmare. Microsoft scrambled to fix the issue and reassure both retailers and consumers, but the damage lingered.

Even with marketing blitzes and the promise of exclusive games, the first shipment of Xbox consoles moved slowly in Japan. Analysts pointed to a mix of cautious gamers, lingering controller complaints, and software that didn’t quite resonate with local tastes. It was a reminder that winning the Japanese market required more than raw power and marketing dollars—it demanded cultural alignment, something Microsoft was still learning on the fly.

March 14, 2002. Launching into a market still loyal to PlayStation 2 and GameCube, Microsoft initially faced cautious skepticism. Early sales were decent but not earth-shattering, so just six weeks after the European launch, they pulled the ultimate power move: a nearly 40% price cut. Gamers who had been sitting on the fence suddenly had little reason to wait, and the Xbox quickly went from “curious newcomer” to serious contender.

Naturally, Microsoft didn’t want to leave early buyers feeling burned. Enter the “thank-you package”: two free games and an extra controller for anyone who had already opened their wallet. It was part apology, part incentive, and part PR masterstroke—a way to keep fans happy while simultaneously pulling new players into the fold.

The aggressive pricing strategy didn’t just move units—it forced the competition to scramble. Suddenly, Sony and Nintendo had to reconsider their own pricing, and a mini console war broke out across Europe. For gamers, it was a win: more options, better deals, and a reminder that Microsoft wasn’t afraid to play rough in a field long dominated by Japanese giants.

Suddenly, Microsoft wasn’t the outsider anymore—it was a force. And while the Xbox wouldn’t win the generation in raw sales, it did something far more important: it earned credibility from skeptical gamers and hardened devs. From a competitive industry that thought Microsoft didn’t have the guts.

They were wrong. The box was here. The war had changed. And Microsoft was in it for the long haul.

Games That Gave the Box a Soul

All the hardware muscle in the world doesn’t matter without games that make you care. And while Xbox launched with the cultural sledgehammer that was Halo: Combat Evolved, its library quickly carved out a unique identity—a blend of cult classics, bold experiments, and underappreciated gems that no other platform dared to touch.

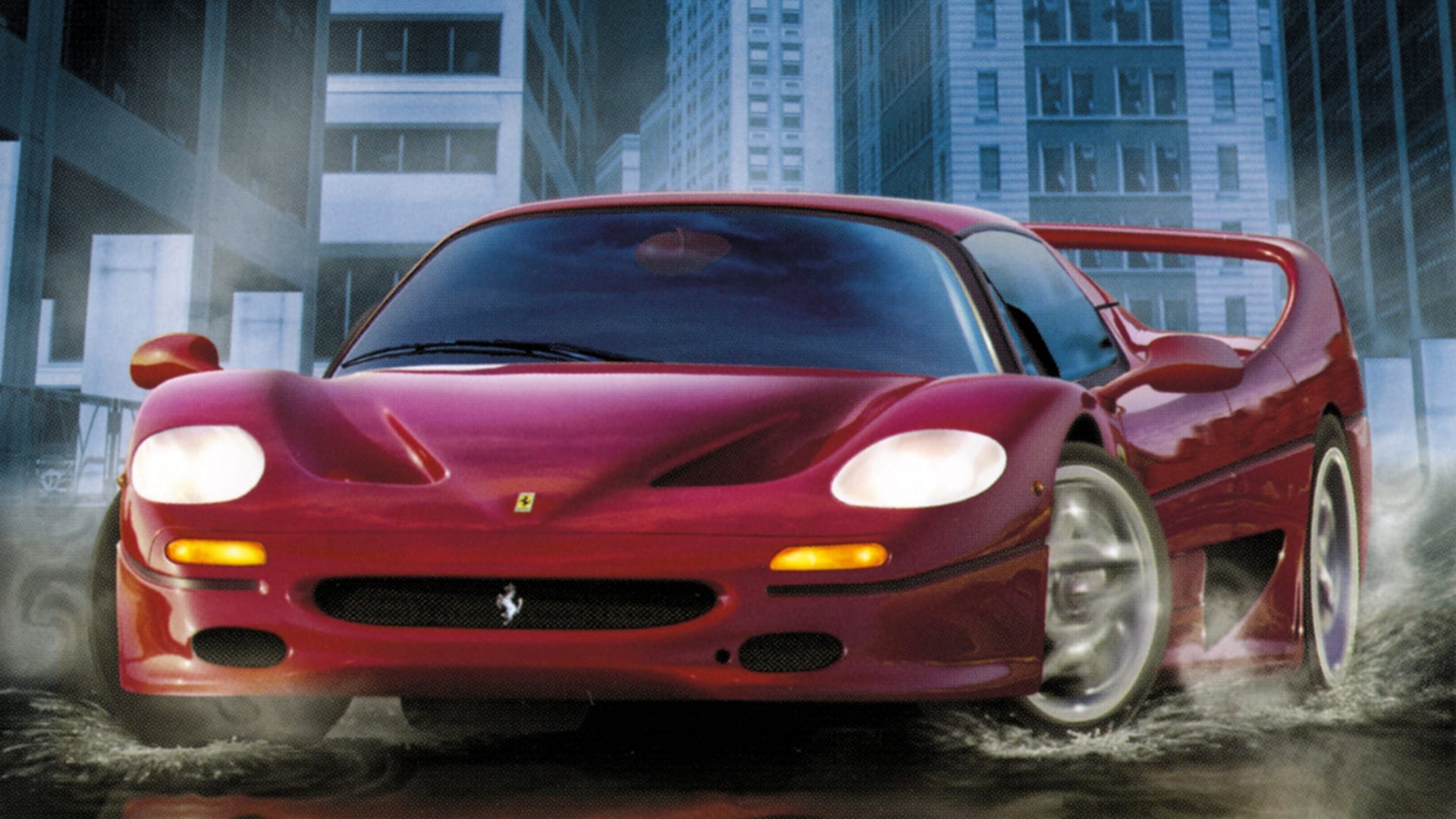

Take Jet Set Radio Future. A stylistic lightning bolt—part graffiti, part rhythm game, part anti-authoritarian fever dream. It wasn’t just visually ahead of its time, it felt like the future. Then there was Project Gotham Racing, a sleek, stylish racer that rewarded flair as much as speed. It didn’t want you to just win. It wanted you to look good doing it.

And who could forget Blinx: The Time Sweeper? Sure, it was divisive. But it was also ambitious, featuring time-manipulation mechanics that were years ahead of their mainstream debut. It wasn’t Mario or Sonic. It was weirder, clunkier, more experimental—and that’s exactly what made it matter.

Then there was MechAssault, stomping onto Xbox Live like a steel colossus. Online multiplayer in a game about walking tanks? Count us in. Dead or Alive 3 brought flash and polish to the fighting scene with its then-unmatched visuals, and Panzer Dragoon Orta revived a Sega classic with gorgeous rail-shooter bliss that felt like digital poetry in motion.

These weren’t just games. They were statements. The original Xbox didn’t rely on legacy franchises—it forged its own. And even if it never matched the PS2 in sheer volume, it delivered experiences you couldn’t get anywhere else. The Xbox wasn’t just flexing tech muscles. It had soul.

The Rise of Xbox Live: Building the Online Console Future

If the Xbox was a statement, Xbox Live was the exclamation point. Launched in 2002, Microsoft’s online service didn’t just connect consoles—it rewired the industry’s DNA. While Sony and Nintendo cautiously dabbled in online functionality, Microsoft barreled forward with a bold, broadband-only platform. No dial-up fallback. No apologies. Just raw, unfiltered latency-busting intent.

It was a gamble. Broadband wasn’t yet ubiquitous. But Microsoft wasn’t aiming for today—they were building for tomorrow. And in that gamble lay genius. Xbox Live introduced a world where players weren’t just statistics on a leaderboard. You had a Gamertag. You had a voice. And suddenly, your friends list was as important as your save file.

Seamless matchmaking, downloadable content, in-game voice chat, the trash talk—concepts we now take for granted were being road-tested on a box that, just a year prior, many had written off as a vanity project from a software megacorp.

Xbox Live wasn’t a feature—it was a revolution. And the original Xbox, once doubted, suddenly felt like the future. Because it was.

Modders, Hackers, and XBMC: The Console That Could Do More

It wasn’t long before gamers realized the Xbox was more than just a console—it was a sleeper PC in disguise. And for a certain breed of tinkerer, that was irresistible.

Crack it open. Flash the BIOS. Install a larger hard drive. Suddenly, the humble Xbox wasn’t just booting up Halo—it was playing ripped DVDs, emulating NES classics, and streaming music across home networks. This wasn’t just hacking. This was repurposing, turning a mass-market game box into a Trojan horse for digital freedom.

At the heart of this underground evolution was Xbox Media Center, or XBMC—a community-built application that transformed the console into a full-blown entertainment hub. With sleek menus, codec support out the wazoo, and a user interface that felt years ahead of its time, XBMC let users do what cable boxes, DVD players, and even PCs couldn’t—everything, all in one place.

XBMC would eventually grow beyond the Xbox, branching off into Plex and Kodi, platforms now found on smart TVs and streaming sticks worldwide. But it all started here. On a hacked console that was never supposed to be this open—or this versatile.

The original Xbox became a cult classic not just because of what it did out of the box, but because of what it could do when you bent the rules. It was the hacker’s darling. A rebel with a green-glowing cause. And in a landscape of locked-down hardware, it was a rare invitation to explore.

The Costs of Ambition: Why the Xbox Lost Money—but Still Won

On paper, the original Xbox was a financial sinkhole. Microsoft lost an estimated $4 billion on the venture. That’s not pocket change. That’s “your shareholders want a meeting” money. But here’s the thing—they knew it would happen. They planned for it.

Because this wasn’t about turning a profit. Not yet. This was about planting a flag. About proving that a company famous for spreadsheets could speak fluent gamer. About building something so compelling, so powerful, so unignorable that it forced an entire industry to take notice. Microsoft didn’t just buy their way into gaming—they brawled their way in.

Every dollar burned on hardware, marketing, and Xbox Live infrastructure was a down payment on the future. The Xbox didn’t make Microsoft rich. But it made Microsoft relevant. And when the Xbox 360 launched just a few years later, the groundwork was already laid. The online service was polished. Developers were on board. The gamers? They were listening.

The original Xbox turned Microsoft from an outsider into a contender. And by the end of its run, it had done something rare in tech: it earned respect. They didn’t just become a gaming company. They proved they belonged. All it took was a mountain of cash, a relentless vision, and a box full of PC parts.

The Legacy of the Original Xbox

The original Xbox wasn’t just different for the sake of it—it was disruptive by design. For the first time, a system spoke the language of developers while still catering to the casual console audience. They introduced things we now take for granted: built-in hard drives, integrated Ethernet ports, and a unified online ecosystem. Features that redefined what a console could be. While the others were refining the past, Xbox was prototyping the future. Game saves without memory cards? Voice chat as a default? Console patches and downloadable content? Xbox planted those seeds.

The Xbox didn’t just challenge Sony or Nintendo; it rewrote the rules for what a console could be. Sure, there were missteps—bulky controllers, slow international launches, and disc issues—but those early stumbles didn’t overshadow the bigger picture: Microsoft had successfully merged two previously separate worlds. Look at the PS5 and Series X today—they’re custom-built gaming PCs in streamlined shells. That lineage starts here.

The original Xbox didn’t win the generation. But it changed the trajectory of all the ones that followed. In the end, it wasn’t just a machine—it was a statement: the living room had a new player, and it was thinking like a PC.