Before the world knew the thundering roar of a Hadouken or the metallic chirp of Mega Man’s blaster, Capcom was tinkering with humble, screenless coin-op contraptions in a small Osaka workshop. Today, it’s a juggernaut—a pop culture monolith whose fingerprints are etched across decades of gaming history. Street Fighter. Mega Man. Monster Hunter. Marvel vs. Capcom. These aren’t just games; they’re institutions, competitive arenas, and creative universes that have shaped entire generations of players. Yet this empire wasn’t born in neon-lit arcades or sprawling development studios.

It began with a handful of dreamers, a gamble on the arcade boom, and a brazen willingness to poach talent from rivals. From its formative years crafting quirky curios to redefining the fighting game landscape and conquering the global market, Capcom’s story is a tale of scrappy beginnings, seismic risks, and an unrelenting drive to entertain. This is the story of how Capcom went from a small arcade company to a name that commands respect in every corner of the gaming world.

Arcade Fever Arrives In Japan

By the late 1970s, Japan was in the grip of a new kind of craze. Space Invaders had stormed the nation’s game halls in 1978, turning dimly lit corners of shopping centers into social battlegrounds. It wasn’t just a hit—it was a phenomenon so intense that reports claimed it caused a temporary shortage of 100-yen coins. Players lined up in packed arcades, cafés, and department stores, eager to test their reflexes against pixelated alien armadas. The arcade was no longer just a smoky hangout for pool tables and pachinko machines—it had become the epicenter of a national obsession.

With the gold rush officially underway, heavyweights like Konami, Namco, Sega, and Nintendo scrambled to stake their claims. Namco delivered titles like Galaxian and Pac-Man that would dominate both Japanese and global markets. Sega pushed technological boundaries with vibrant visuals and unique control schemes, while Konami churned out addictive shooters and quirky action games. Even Nintendo, not yet the console powerhouse it would become, made strategic moves into arcade cabinets, laying the groundwork for its future dominance.

Before the invasion of microchips and cathode-ray screens, Japan’s amusement floors were filled with electro-mechanical curios—whirring gears, blinking lights, and mechanical targets. But video games changed everything. The appeal was immediate: deeper interaction, evolving challenges, and graphics that could transport players to alien worlds, battlefields, and fantasy realms. This transition wasn’t just technological—it was cultural. The industry was on the brink of a transformation, and those with the foresight to embrace pixel-based entertainment stood to shape the future of play itself.

Humble Beginnings in Osaka

In 1979, Kenzo Tsujimoto was already navigating the competitive waters of Japan’s arcade industry as the founder of Irem, a company destined to be remembered for the legendary R-Type. But Tsujimoto was a man with restless ambition. While keeping Irem on course, he quietly began laying the foundation for another venture—one that would give him the freedom to experiment beyond the established company’s direction. This wasn’t an impulsive side hustle; it was a strategic hedge, a way to keep one foot in the rapidly evolving world of amusement machines while scouting fresh territory for the future.

Osaka, Japan’s commercial heartbeat, was more than just a convenient headquarters—it was fertile ground for a rising game company. The city’s dense network of electronics suppliers, manufacturing plants, and shipping routes made it an ideal hub for producing and distributing coin-operated machines. Osaka’s business culture thrived on speed, pragmatism, and innovation—traits that would become hallmarks of Tsujimoto’s approach. And in a city that balanced traditional craftsmanship with forward-thinking technology, the conditions were ripe for a startup to grow from local curiosity to national contender.

By the dawn of the 1980s, the arcade landscape was changing almost monthly. The mechanical amusements of the previous decade—pinball, shooting galleries, and light-based attractions—were giving way to interactive video experiences. Tsujimoto saw the writing on the wall. The future wasn’t just about building machines; it was about creating worlds, mechanics, and challenges that would keep players coming back. That vision would become the driving force behind his new company, setting the stage for Capcom’s evolution from humble manufacturer to one of gaming’s most influential creative powerhouses.

The Birth of I.R.M. Corporation

In 1979, Kenzo Tsujimoto officially launched I.R.M. Corporation in Osaka, with a vision that was pragmatic rather than grandiose. This was not yet a company gunning for the arcade crown or battling for high-score supremacy. Instead, I.R.M.’s early mandate was simple: design, manufacture, and sell dependable electronic game machines to operators across Japan. The goal was steady business, not headlines—a way to carve out a niche by serving the needs of local game halls, cafés, and entertainment centers. It was a foundation built on practicality rather than flashy innovation, but that foundation would prove vital.

Before its transformation into a video game titan, I.R.M.’s bread and butter was mechanical amusement machines. These devices didn’t need CRT monitors or pixel art; they relied on clever engineering, light effects, and tactile gameplay. A ball would drop, lights would flash, and sounds would chime—simple mechanics that were perfect for drawing in casual players. In a way, they were designed for accessibility before that became a buzzword. Small arcades and neighborhood cafés loved them because they were easy to maintain, inexpensive to operate, and had a universal appeal that crossed age groups.

Every successful game company needs more than good ideas—it needs the infrastructure to bring those ideas to life and into paying venues. During its early years, I.R.M. quietly built the operational backbone that would one day allow Capcom to scale quickly. Relationships with parts suppliers, contracts with machine operators, and a dependable distribution network all took shape during this period. By proving itself a reliable partner to arcade owners, I.R.M. gained something far more valuable than short-term profits: trust. And in the entertainment business, trust opens doors long before a smash-hit game doe

Japan Capsule Computer: The Name That Almost Stuck

By 1981, I.R.M. was ready to evolve. Tsujimoto established a subsidiary called Japan Capsule Computer Co., Ltd., signaling a shift toward a more ambitious and forward-looking direction. This wasn’t just about selling mechanical amusements anymore—this was a calculated move to carve out a distinct identity focused on interactive entertainment. The new subsidiary gave the company a dedicated brand under which it could experiment, innovate, and eventually step into the booming video arcade scene without abandoning its core business.

The name “Japan Capsule Computer” might sound odd today, but in the early ’80s, it was rooted in a specific vision. The “capsule” represented a complete, self-contained entertainment package—hardware and software fused into a single unit, ready for play the moment it was plugged in. The term “computer” lent it a futuristic edge, aligning with Japan’s growing fascination with electronics and the promise of digital technology. It was branding meant to suggest both sophistication and accessibility.

While “Japan Capsule Computer” was functional, it wasn’t exactly snappy. In an industry where memorability mattered as much as quality, Tsujimoto recognized the need for a sharper, more marketable name. The solution was simple but brilliant: shorten and merge the two key words into Capcom. It was short, punchy, and easy to pronounce across languages—an early sign that Tsujimoto was thinking beyond Japan’s borders. That concise new name would soon be stamped on cabinets, cartridges, and consoles around the globe, carrying with it a legacy that began with a simple branding tweak.

Capcom is Born

By 1983, the pieces were finally falling into place. I.R.M. had already rebranded its manufacturing arm as Sanbi, but Tsujimoto wanted a clear, unified identity for the company’s future in entertainment. That year, Sanbi and Japan Capsule Computer Co., Ltd. were merged, streamlining operations under a single, newly established banner—Capcom Co., Ltd. This wasn’t just an administrative formality; it was the official starting gun for a company that would soon help define the arcade boom of the mid-1980s.

Capcom’s first releases weren’t what you might expect. Instead of arcade video games, their debut products—Little League and Fever Chance—were mechanical amusement machines. Little League was a baseball-themed game where players batted a ball bearing into scoring zones, while Fever Chance offered a pachinko-like experience with flashing lights and a touch of gambling-style thrill. Both catered to a market that still valued tactile, physical gameplay, especially in smaller arcades and cafés where full-sized video cabinets weren’t always practical.

In 1983, video arcade games were hot, but they were also expensive to develop and produce. Monitors, circuit boards, and the expertise to create engaging pixel-based gameplay required significant upfront investment—and Capcom wasn’t ready to bet the farm just yet. Mechanical games had lower production costs, were easier to maintain, and could be sold to a wider range of operators, including those who didn’t have the budget or space for large video cabinets. For Capcom, these early mechanical amusements were a smart, low-risk way to build manufacturing expertise, cultivate operator trust, and generate revenue—laying the foundation for the leap into video arcades that would come just a year later.

The Great Talent Raid from Konami

By the early 1980s, Konami wasn’t just another arcade game maker—it was a hit factory. Titles like Scramble (1981) helped pioneer the scrolling shooter, while Frogger (1981) became a global cultural touchstone. Behind those successes was a pool of fiercely creative designers and programmers whose work was turning Konami into an arcade powerhouse. But talent like that never stays unnoticed for long—especially by ambitious rivals looking to make a name for themselves.

Tokuro Fujiwara had already earned a reputation for crafting addictive arcade experiences. Pooyan (1982) was a charming but challenging twist on the shooting genre, while Roc’n Rope (1983) introduced a grappling mechanic that predated the platformer boom. Fujiwara wasn’t just making games—he was experimenting with new forms of player interaction, a quality that would soon become invaluable to Capcom’s creative DNA.

Yoshiki Okamoto was another rising star, known for high-concept arcade action with impeccable gameplay feel. Time Pilot (1982) offered 360-degree movement in a scrolling shooter—a technical marvel for its time—while Gyruss (1983) blended space shooting with circular movement inspired by Tempest. Okamoto’s knack for merging innovative controls with pure arcade adrenaline made him a high-value hire for any company looking to break into the big leagues.

Capcom’s coup wasn’t just poaching one or two individuals—it was strategically importing a brain trust. Fujiwara and Okamoto didn’t work on the same projects; instead, Capcom split them into separate development teams, ensuring their creativity wouldn’t cannibalize each other but instead drive parallel streams of innovation. This move immediately boosted Capcom’s development muscle, setting the stage for the company’s first wave of video arcade hits. In hindsight, it wasn’t just a hiring spree—it was the start of Capcom’s transformation from a cautious mechanical amusement maker into a fearless arcade innovator.

The First True Video Game: Vulgus

Capcom’s first fully fledged video arcade title, Vulgus, arrived in 1984, and if it felt familiar to arcade-goers, that was no accident. Namco’s Xevious (1982) had set the gold standard for vertical shooters, with its layered enemy patterns, scrolling landscapes, and dual-attack system. Vulgus followed that template closely—players piloted a lone fighter craft through endless waves of enemies, blasting airborne foes while dropping bombs on ground targets. The influence was so pronounced that Vulgus felt like Capcom’s proof-of-concept for its entry into video gaming: “We can do this too, and we can do it fast.”

Development on Vulgus was astonishingly quick—just three months from initial design to finished arcade cabinet. That speed came partly from necessity: Capcom was still a newcomer in the video game space and needed to prove to arcade operators that it could deliver competitive products on schedule. This meant tight coordination between the small design team, hardware engineers, and cabinet manufacturers. Every feature, from enemy behavior to sound effects, was developed with both creative ambition and production deadlines in mind.

When Vulgus hit arcades, it performed modestly—good enough to keep operators happy but nowhere near the blockbuster levels of Pac-Man, Donkey Kong, or even Xevious. However, the true value of Vulgus wasn’t in its earnings—it was in what Capcom learned. The company gained hands-on experience with video game hardware, refined its manufacturing pipeline for arcade boards, and began to understand the delicate balance between challenge, accessibility, and visual appeal that defined arcade success. Most importantly, Vulgus established Capcom’s first in-house game engine foundations—building blocks that would evolve in their next projects. If Vulgus wasn’t yet a Capcom classic, it was the company’s first confident step into the arena it would soon dominate.

The Breakout Hit: 1942

Hot on the heels of Vulgus, Capcom doubled down on the vertical shooter formula but added a historical hook. 1942 traded the sci-fi trappings for a stylized World War II Pacific theater setting, putting players in the cockpit of a P-38 Lightning. It wasn’t just another “shoot everything that moves” arcade game—it introduced a signature evasive maneuver: the roll, or “loop-de-loop.” At the push of a button, your plane would flip out of harm’s way, dodging enemy fire and creating breathing room in the chaos. Combined with bomb attacks and wave-based enemy formations, this small but satisfying mechanic gave the game a unique rhythm and set it apart from its space-bound peers.

In Japan, 1942 was a smash hit. The historical theme resonated, the pacing was tight, and the difficulty curve struck that perfect arcade balance—just punishing enough to keep players coming back, but not so overwhelming that newcomers walked away in frustration. This was Capcom’s first game to earn widespread recognition from both arcade operators and players. Overnight, the company went from “those Vulgus guys” to a studio worth paying attention to.

When 1942 crossed into North American arcades in 1985, expectations were modest. After all, WWII shooters weren’t exactly mainstream in the West, and the idea of playing as an Allied fighter pilot taking down Japanese aircraft could have been a sensitive subject. Yet, the game’s crisp controls, clean visuals, and addictive loop mechanic made it an unexpected hit. In the U.S. and Europe, 1942 carved out a niche among competitive high-score chasers and casual arcade-goers alike.

Financially, 1942 was a turning point. It brought in the kind of consistent coin-drop revenue that arcade operators loved, which in turn made them more willing to take a chance on future Capcom titles. The profits gave Capcom breathing room to expand its development teams, invest in better arcade hardware, and start experimenting with more ambitious game concepts. Capcom had its first true blockbuster, and the momentum it generated would carry the company into the next phase of its arcade legacy.

Capcom Meets the NES

By the mid-1980s, Nintendo’s Famicom had already taken Japan by storm, and the NES was beginning to gain traction in North America after the market-crushing video game crash of 1983. For arcade developers, the message was clear: if you wanted your games to reach living rooms, you had to play nice with Nintendo. Capcom’s 1942 was among the early wave of third-party titles licensed for the Famicom/NES, and its presence on the platform came with an unspoken badge of honor—Nintendo’s famously strict seal of quality. While the NES port couldn’t replicate the arcade’s smooth scrolling or sprite detail, it captured the addictive gameplay loop, cementing 1942 as a hit beyond the arcade floor. For many players, the NES version was their first taste of Capcom, and that kind of brand introduction was priceless.

Once the NES relationship was established, Capcom started flexing creative muscles beyond its vertical shooter roots. Trojan was an early attempt to blend side-scrolling action with weapon-based combat, giving players a sword-and-shield moveset that felt distinct from the more straightforward Kung-Fu Master style brawlers. But it was Bionic Commando that truly stood out—a game that defied genre conventions by removing the jump button entirely and replacing it with a grappling bionic arm. On paper, it sounded like a limitation; in practice, it became a defining mechanic. While the arcade version had its fans, it was the NES adaptation that elevated Bionic Commando into a cult classic, with expanded levels, story elements, and more refined gameplay.

In the arcade business, a game’s revenue potential was tied directly to how long people were willing to pump quarters into it. Once interest faded, the income stream dried up. Home console ports changed that equation. By adapting arcade hits for the NES, Capcom could extend a game’s lifespan by years, tapping into a whole new audience that might never step foot in a game center. More importantly, NES titles carried higher profit margins and allowed Capcom to build recurring relationships with customers—if someone bought 1942 for their NES, they might be far more likely to pick up Ghosts ’n Goblins or Mega Man down the road.

The NES partnership wasn’t just a side hustle for Capcom—it was the foundation of a long-term business model that would see the company thrive across both arcade and home console markets for decades to come.

The Birth of Mega Man

By 1987, Capcom was building a reputation as a reliable arcade and NES developer, but it didn’t yet have a mascot—no plumber, no blue hedgehog, no signature character to call its own. Enter Keiji Inafune, a young illustrator fresh out of college, who joined Capcom as an artist and immediately left his mark. While Mega Man (known as Rockman in Japan) was already in early planning stages when Inafune came aboard, his hand was instrumental in refining the character’s look and personality. Inspired partly by Japanese anime heroes and partly by the technical constraints of the NES’s limited color palette, Inafune gave the Blue Bomber his now-iconic cyan armor, rounded helmet, and expressive eyes. The result was a design that was simple enough for 8-bit hardware but memorable enough to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with gaming’s emerging icons.

In an era where most action-platformers marched players through a fixed sequence of stages, Mega Man dared to be different. The game’s stage select screen let players tackle its six Robot Masters in any order they wished, and that choice mattered. Each boss dropped a unique weapon upon defeat, and certain weapons were particularly effective against specific other bosses. This “rock-paper-scissors” mechanic added an element of strategy that went beyond twitch reflexes, rewarding experimentation and replayability. Players quickly discovered optimal boss orders, but the thrill of figuring it out for yourself became part of Mega Man’s lasting appeal.

While the first Mega Man wasn’t an overnight commercial sensation, it laid the foundation for one of Capcom’s most enduring franchises. The character’s bright, heroic design and adaptable moveset made him a perfect frontman for the company. Sequels followed almost immediately, refining the gameplay and expanding the roster of Robot Masters, and with each release, Mega Man’s profile grew. By the early ’90s, he wasn’t just a game character—he was Capcom’s brand ambassador, appearing in comics, cartoons, and a flood of merchandise.

Looking back, Mega Man’s debut marked a shift for Capcom—from a studio chasing arcade trends to one capable of creating evergreen franchises with characters that could stand the test of time. This little blue robot didn’t just fight evil; he helped define Capcom’s identity for the next two decades.

Street Fighter’s First Round

Before Street Fighter II became a cultural juggernaut, Capcom’s first entry in the series was more of a bold experiment than a polished product. Released in 1987, Street Fighter introduced players to Ryu and Ken—names that would soon become synonymous with the fighting genre—and tasked them with traveling the globe to challenge martial arts masters. Its most unusual feature? Pressure-sensitive punch and kick buttons that registered different attack strengths depending on how hard you hit them. It was a novel idea, but also one that caused more sore hands and broken cabinets than tournament-level strategy.

On paper, Street Fighter had all the makings of a hit: a globetrotting martial arts premise, cinematic special moves, and a unique control gimmick. In practice, it was clunky. The hit detection was inconsistent, the special move inputs were finicky to the point of feeling accidental, and the button gimmick—while innovative—was expensive to maintain for arcade operators. Most players walked away frustrated rather than hooked, and it didn’t exactly spark a competitive scene. Still, the ambition was there: digitized voice samples, recognizable character designs, and the idea of one-on-one fighting as the entire game, not just a bonus mode.

Despite its shortcomings, Street Fighter planted seeds that would grow into one of gaming’s biggest phenomena. It established Ryu and Ken as rivals, introduced the concept of special move commands (Hadouken, Shoryuken, Tatsumaki), and proved that head-to-head arcade competition could be more than a passing novelty. The lessons learned—about control responsiveness, character variety, and accessibility—would directly inform Street Fighter II’s design just four years later. If the first Street Fighter was an awkward sparring match, the sequel would be the knockout punch that forever changed the arcade landscape.

The Capcom Yashichi Origin

Before Mega Man’s E-Tanks and Street Fighter’s Hadoukens became Capcom’s most recognizable icons, there was another—smaller, stranger symbol quietly spinning in the background of their early history: the Yashichi. This colorful pinwheel emblem, often hidden away in Capcom’s earliest arcade games, has been a fixture of the company’s visual DNA since the beginning. But its origin doesn’t come from gaming—it comes from television.

Japan’s longest-running TV drama, Mito Kōmon (水戸黄門), aired from 1969 to 2011 and told the story of traveling heroes righting wrongs in Edo-period Japan. Think of it as a samurai-era version of The A-Team: a band of noble wanderers helping villagers against corrupt officials and criminals. Among its beloved cast was Kazaguruma no Yashichi (風車の弥七)—literally “Yashichi of the Windmill.” The character hailed from a town called Yashichi and wielded a distinct weapon: a thrown metal spike concealed in the handle of a red pinwheel.

Capcom borrowed both the name and the motif. The spinning windmill became a recurring emblem in their earliest games, first appearing as an enemy and later evolving into a secret item—usually granting a massive score bonus or an extra life. Players might spot it tucked away in titles like Vulgus or 1942, not realizing the cultural lineage behind it.

While most modern write-ups cite a mention from Game Center CX as the origin of this trivia, Capcom themselves confirmed the connection decades earlier—in a Capcom History feature published in Gamest’s Street Fighter II’ Champion Edition Special issue back in 1992. The Yashichi isn’t just a collectible trinket—it’s a nod to Capcom’s roots in Japanese pop culture, a tiny emblem of the company’s creative DNA that continues to spin, both literally and metaphorically, through decades of gaming history.

Late ’80s Expansion & Experimentation

By the late 1980s, Capcom had proven it could deliver arcade hits, but the company wasn’t content with sticking to one formula. This era was defined by a willingness to branch out into new genres, test new ideas, and establish franchises that would last for decades.

Strider (1989)

Cinematic Action and Bold Visual Flair: Based on a manga collaboration with Moto Kikaku, the game put players in control of Hiryu, a futuristic ninja armed with a plasma sword, acrobatics, and a flair for the dramatic. The action was fluid and relentless, with set pieces like scaling a giant mechanical centipede or battling enemies in zero gravity. Strider’s backgrounds were richly detailed, its animations crisp, and its globe-hopping stages—from Soviet-inspired fortresses to lush Amazon jungles—felt like a playable action movie.

Final Fight (1989)

Side-Scrolling Brawlers At Their Peak: Originally conceived as a sequel to Street Fighter, the game evolved into its own powerhouse, introducing players to Cody, Guy, and the unforgettable Mayor Mike Haggar—arguably the only mayor in history who settles political disputes by piledriving gang members. With its huge, colorful sprites, satisfying combat system, and cooperative two-player mode, Final Fight became the gold standard for the beat ’em up genre. Its urban setting and gang-war storyline gave it a gritty edge that appealed to Western players, while the sheer visual punch of the CPS-1 arcade board made it a showpiece for operators.

SonSon II (1989)

An Homage to the Past with RPG Flair: As a follow-up to Capcom’s early 1984 arcade title SonSon, this PC Engine-exclusive sequel transformed the formula. Instead of a straightforward arcade shooter, SonSon II leaned into action-adventure and light RPG elements, offering a deeper experience than its predecessor. It showed Capcom’s growing interest in blending genres and experimenting with home console audiences.

The Street Fighter II Explosion

When Street Fighter II hit arcades in 1991, it didn’t just improve on the original—it rewrote the rulebook for fighting games. Capcom refined the control scheme into the now-standard six-button layout, giving players precise control over light, medium, and heavy punches and kicks. The roster—eight distinct fighters from around the world—was a perfect balance of accessibility and depth, each with unique special moves that could be learned but took skill to master. Fireballs, dragon punches, and spinning piledrivers weren’t just attacks—they were statements. And for the first time, players could pit different characters against each other in endlessly varied matchups, turning mastery into an art form.

Street Fighter II transformed arcades from casual hangouts into competitive battlegrounds. Crowds gathered around cabinets to watch matches, cheer on local heroes, and see who could keep their quarter up the longest. This game didn’t just popularize competitive fighting—it sparked the birth of organized tournaments, local “arcade champions,” and an early version of the fighting game community (FGC). The buzz around SFII helped keep arcades alive well into the ’90s, even as home consoles began to dominate.

The game’s success spilled far beyond arcades. Capcom licensed Street Fighter II for action figures, trading cards, manga adaptations, and Saturday morning cartoons. Characters like Ryu, Chun-Li, and Guile became gaming icons recognized worldwide, and the brand’s reach extended into pop culture in ways few arcade games ever had. By the early ’90s, Street Fighter II wasn’t just a hit game—it was a global entertainment phenomenon, cementing Capcom as one of the most influential game developers of the era.

Capcom in the 1990s: Expanding the Playbook

By the mid-90s, Capcom wasn’t just “the Street Fighter company” anymore—it was evolving into a creative machine that could take risks across multiple genres. The arcade scene was still its bread and butter, but the rise of the PlayStation, Saturn, and later the Dreamcast meant new opportunities to experiment, expand franchises, and reach players who might never step foot in an arcade.

Mega Man X (1993)

Updating the Mascot: By the early ’90s, the original Mega Man series was showing signs of formula fatigue—still beloved, but in need of a shake-up. Mega Man X for the Super Nintendo delivered exactly that. This wasn’t just the Blue Bomber with better graphics; X was sleeker, faster, and equipped with wall jumps, dashes, and a grittier, more mature storyline. The tone shifted from cartoon charm to sci-fi intensity, introducing darker themes and higher stakes without losing the tight, precision platforming fans loved. Mega Man X didn’t just revive interest in the brand—it established a sub-series that would stand proudly alongside Street Fighter II as one of Capcom’s defining 16-bit achievements.

X-Men: Children of the Atom (1994)

The Marvel Crossover Era Begins: Before Marvel vs. Capcom became an institution, Capcom cut its teeth on Marvel fighters with X-Men: Children of the Atom. It was the company’s first fighting game to use Marvel’s iconic superheroes, with wild, screen-filling special moves and aerial combos that pushed the genre into new territory. Not only did it set the stage for X-Men vs. Street Fighter and the legendary Marvel vs. Capcom series, but it also proved Capcom could take a licensed property and make it sing in the arcade.

Rival Schools (1997)

High School Spirit Meets Hard-Hitting Combat: Never one to shy away from experimentation, Capcom tried something new with Rival Schools: United by Fate. A 3D fighter with a vibrant, anime-style presentation, it combined over-the-top tag-team brawling with a surprisingly heartfelt story about friendship, teamwork, and school pride. The cast—ranging from hot-blooded delinquents to eccentric teachers—was pure Capcom quirkiness. While it never achieved the mainstream success of Street Fighter, it developed a cult following and showed Capcom was willing to think outside the box.

Street Fighter Alpha 3 (1998)

The Pinnacle of 2D Fighting: While Street Fighter II was the legend that started it all, the Alpha series gave Capcom the freedom to reimagine its cast with flashier visuals, new mechanics, and anime-inspired flair. Street Fighter Alpha 3 was the crown jewel—introducing “Isms” (different fighting styles), a massive roster, and some of the slickest sprite work Capcom ever produced. It was proof that the company could keep the 2D fighting genre fresh even as the industry began chasing 3D graphics.

Marvel vs. Capcom (1998)

Fan Service Done Right: When Marvel vs. Capcom hit arcades in 1998, it wasn’t just another fighter—it was an all-out fireworks display of chaotic fun. This was the ultimate fantasy matchup—Spider-Man trading blows with Ryu, Chun-Li kicking alongside Captain America, Wolverine tearing through Zangief. Capcom’s CPS-2 hardware allowed for lightning-fast tag-team battles, massive multi-hit combos, and super moves that filled the entire screen with comic-book spectacle. Players could swap characters mid-battle, chain specials into supers, and unleash hyper combos that turned matches into explosive bursts of color and sound.

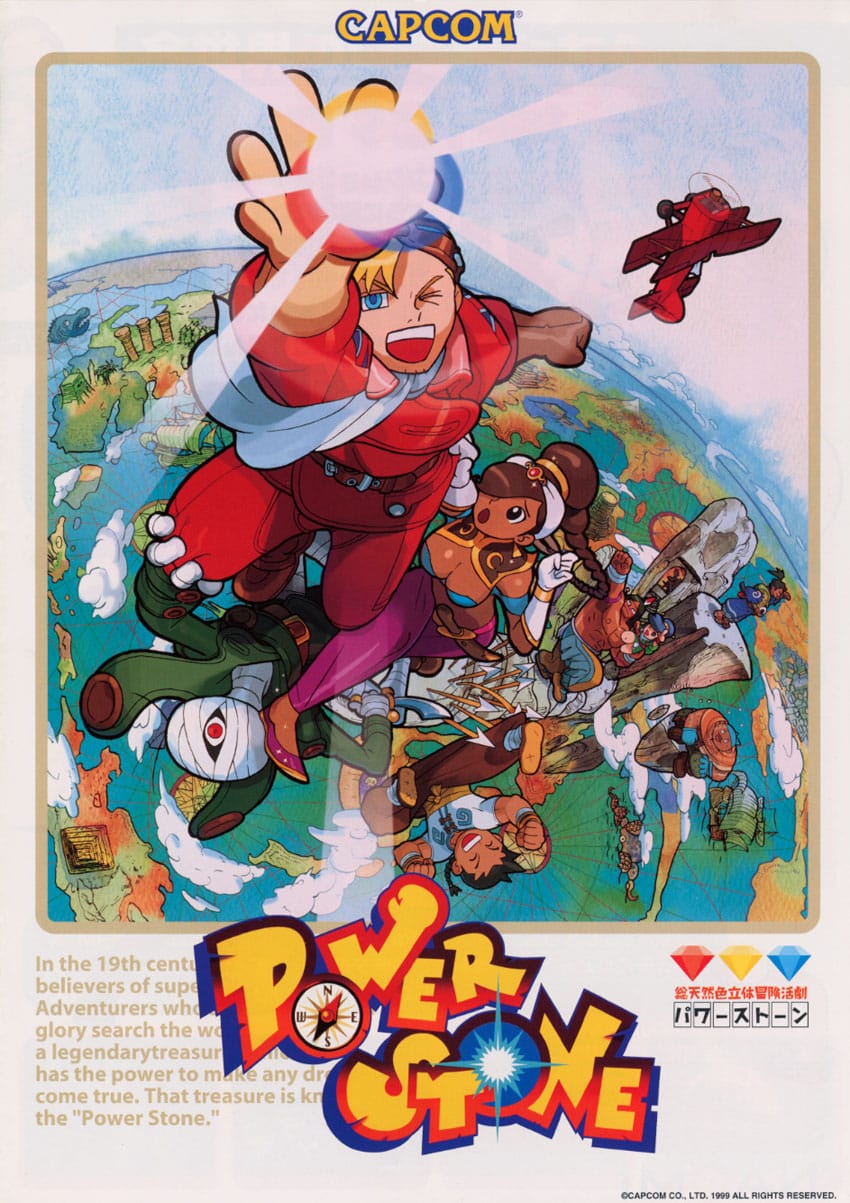

Power Stone (1999)

3D Fighting Mayhem: Capcom capped off the decade with one of its boldest experiments: Power Stone. Released on Sega’s Dreamcast, it broke away from traditional one-on-one fighting to embrace a free-roaming, arena-based brawler. Players could smash each other with improvised weapons, interact with the environment, and transform into super-powered versions of themselves once they collected all the Power Stones. It was chaotic, colorful, and way ahead of its time—laying the groundwork for modern arena fighters and even influencing Nintendo’s Smash Bros. series.

Street Fighter III: 3rd Strike (1999)

Technical Mastery and a Cult Following: While Street Fighter II had already become a global phenomenon, Capcom wasn’t afraid to take risks with its successor. Street Fighter III introduced an almost entirely new cast (a bold move that initially divided fans) and a more technical combat system centered around parrying—a high-risk, high-reward mechanic that rewarded perfect timing and mastery. The pinnacle of this design came with Street Fighter III: 3rd Strike, released in 1999, which fine-tuned the mechanics to near perfection. Though it never reached the mainstream popularity of its predecessor, 3rd Strike developed a fiercely loyal competitive community.

Capcom in the 2000s: New Millennium, New Battles

As gaming crossed into the 2000s, Capcom faced a challenge. Consoles were moving to 3D as the standard, handhelds were evolving beyond simple 2D sprite shows, and audiences were starting to embrace online connectivity in bigger ways. Capcom’s answer wasn’t to retreat into nostalgia—it was to create bold new IPs, daring stylistic shifts, and genre-bending risks. Some even became stepping stones to even greater things down the road.

Marvel vs. Capcom 2 (2000)

The Ultimate Crossover Chaos: You want fan service? MvC2 delivered it in seismic waves. With 56 characters—from Ryu and Iron Man to obscure deep cuts like Marrow—Capcom's chaotic crossover was a fever dream made real. NAOMI’s extra RAM allowed for tag-team mayhem, lightning-fast load times, and screen-filling hyper combos that could crash older boards. It became a tournament staple, a pop culture icon, and a reason for arcade-goers to keep stacking quarters.

Capcom vs. SNK: Millennium Fight 2000 (2000)

Rivalries Made Real: Fans had dreamed about it for years: Capcom’s world-class roster going head-to-head with SNK’s legends. In 2000, Capcom vs. SNK made that fantasy real. Released in arcades and on the Dreamcast, it blended Capcom’s polished fighting systems with SNK’s distinct flair, letting players finally pit Ryu against Kyo or Chun-Li against Mai. While its balance wasn’t perfect, it was a crossover event of seismic proportions that energized the fighting game scene.

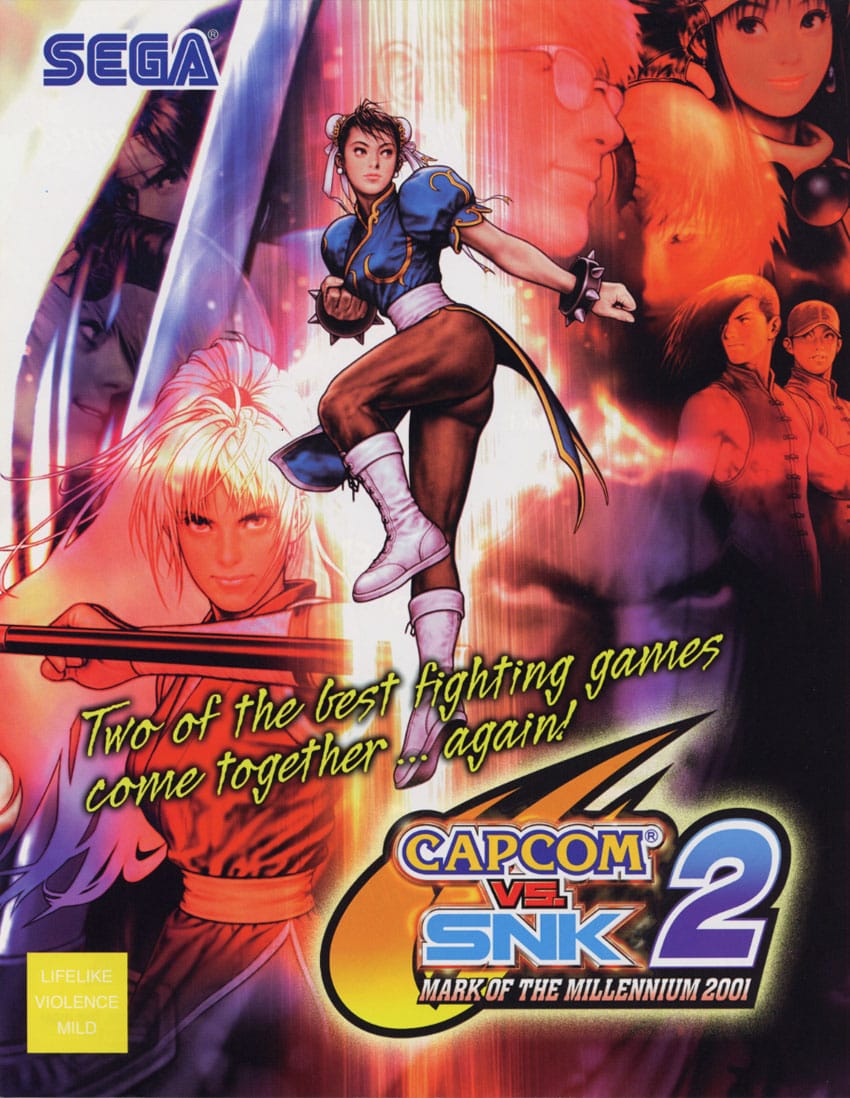

Capcom vs. SNK 2: Mark of the Millennium 2001 (2001)

Refining the Formula: Capcom didn’t stop there. A year later, it followed up with Capcom vs. SNK 2, which expanded the roster dramatically and introduced the “Groove” system, allowing players to adopt different fighting styles inspired by both companies’ mechanics. For many fans, this remains one of the most polished crossover fighters ever made, and it solidified Capcom as the undisputed master of genre mashups.

Mega Man Battle Network (2001)

The Blue Bomber Reimagined: By the early 2000s, the classic Mega Man formula was beginning to feel a little tired. So Capcom reinvented the Blue Bomber for a new generation of handheld gamers. Enter Mega Man Battle Network, a tactical RPG-meets-collectible card game hybrid for the Game Boy Advance. Instead of side-scrolling stages, players controlled Lan Hikari and his NetNavi, MegaMan.EXE, battling viruses on a 6x3 grid with chips that acted like attacks, spells, or support moves. It was a bold departure that clicked with the GBA audience, spawning multiple sequels and even an anime adaptation. Battle Network was proof that Mega Man could evolve without losing his core identity.

Viewtiful Joe (2003)

Superheroes, Cel-Shading, and Pure Style: Capcom’s Clover Studio made a name for itself with Viewtiful Joe, a side-scrolling beat-’em-up that combined old-school gameplay with a striking, comic book-inspired cel-shaded art style. Joe, an average moviegoer-turned-superhero, battled across film reels using “VFX powers” that let him slow down, speed up, or zoom in on the action. It was quirky, stylish, and unlike anything else on the market. While Viewtiful Joe never hit blockbuster numbers, it was a critical darling and became one of Capcom’s defining cult classics of the era, laying the groundwork for Clover’s later masterpieces like Okami.

Mega Man X8 (2004)

Back to Basics in the X Series: The Mega Man X series had a rough patch with the universally panned X7, which clumsily attempted a 3D transition. With Mega Man X8, Capcom course-corrected, returning to a hybrid 2.5D style that felt truer to the series’ roots while still looking modern. It may not have reached the legendary heights of X4, but X8 was a solid redemption arc for the series—delivering tight platforming, multiple playable characters, and a soundtrack that reminded fans why they fell in love with the X series in the first place. For many, it was a final hurrah before the franchise went into hibernation.

Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney (2005)

Objection! Courtroom Chaos: One of Capcom’s strangest risks became one of its most beloved series. Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney wasn’t an action game, a fighter, or even a platformer—it was a visual novel about solving crimes in the courtroom. Players stepped into the shoes of rookie defense attorney Phoenix Wright, cross-examining witnesses, spotting contradictions, and delivering the iconic “Objection!” at just the right moment. On handhelds, it proved there was room for slower, narrative-driven games alongside flashy action titles. For Capcom, it opened the door to a whole new kind of storytelling franchise.

Monster Hunter Freedom Unite (2008)

The PSP Phenomenon: If the original Monster Hunter was a cult hit, Freedom Unite turned it into a national obsession in Japan. On the PSP, it became the definitive portable multiplayer experience—friends gathering in cafes, trains, and classrooms to slay giant beasts together. It was here that the franchise became a cultural force, cementing Monster Hunter as one of Capcom’s crown jewels.

Dawn of a New Capcom: The HD Fighting Renaissance

When the seventh generation of consoles (Xbox 360, PlayStation 3) ushered gaming into the high-definition era, many publishers struggled to adapt. Development costs skyrocketed, trends shifted, and the appetite for online play exploded. Capcom, however, saw the HD leap as an opportunity: not just to revive its most iconic franchises, but to reassert its dominance in the fighting game arena and keep its arcade roots alive in a modern age.

Street Fighter IV (2008)

Fighting Games Return To The Spotlight: By the mid-2000s, fighting games had largely retreated from the mainstream, surviving mainly through die-hard competitive scenes. Then Street Fighter IV arrived, striking like a perfectly timed Hadouken. Capcom struck gold by blending the fundamentals of 2D gameplay with flashy new 3D character models rendered on a 2.5D plane. The game was immediately approachable but retained the depth and precision the series was known for. Midnight launches, packed arcades, and grassroots tournaments surged once more, revitalizing not just Street Fighter, but the entire fighting game ecosystem. Capcom had not only revived Street Fighter, but the entire fighting game industry.

Super Street Fighter IV (2010)

The Definitive Upgrade: Never one to let momentum slip, Capcom followed up with Super Street Fighter IV. More than just a re-release, it expanded the roster with fan favorites like Cody, Juri, and Guy, added new Ultra Combos, and polished gameplay balance to near-perfection. For competitive players, Super became the definitive standard, the version that dominated tournaments and reigned supreme in arcades. It also showed Capcom’s old-school mentality hadn’t faded: just like the Street Fighter II days, incremental updates and refinements weren’t cash grabs—they were how you kept a competitive scene alive and thriving.

Marvel vs. Capcom 3 (2011)

The Crossover Returns: After a decade-long absence, Capcom resurrected one of its most chaotic and beloved series: Marvel vs. Capcom. In a gaming landscape where superhero films were beginning to dominate pop culture, the timing was perfect. Marvel vs. Capcom 3 delivered everything fans expected: lightning-fast tag-team action, a ridiculous roster mashing comic book icons with Capcom legends, and over-the-top supers that lit up screens like fireworks. While its balance was shaky and the meta-game a bit rough, it reminded everyone why the series had been such an arcade darling in the late ’90s.

Ultimate Marvel vs. Capcom 3 (2011)

From Cult Favorite to Tournament Staple: Just months later, Capcom released Ultimate Marvel vs. Capcom 3. At the time, some fans saw it as too soon, but history proved otherwise. With a refined roster, tweaked mechanics, and the addition of characters like Vergil, Hawkeye, and Rocket Raccoon, UMvC3 became the definitive version. The game’s fast-paced, high-risk, high-reward style turned it into a spectator sport as much as a fighting game. Streamed matches drew thousands of viewers, helping cement fighting games as a pillar of the esports boom. To this day, UMvC3 is remembered as one of the most influential competitive fighters of the HD era.

Street Fighter X Tekken (2012)

A Clash of Titans: Riding high on crossover success, Capcom took things even further by teaming up with Bandai Namco for Street Fighter X Tekken. On paper, it had everything—a deep roster, flashy tag-team mechanics, and fan-favorite dream matches that fans had speculated about for years. And while it had its merits, the game quickly became infamous for controversial decisions: locked DLC characters already present on the disc, an unpopular “Gem System” that complicated balance, and a meta that never fully satisfied either Street Fighter or Tekken loyalists. Still, despite its flaws, Street Fighter X Tekken showcased Capcom’s ambition. It was proof that the company was willing to take risks—even if the execution sometimes stumbled.

Ultra Street Fighter IV (2014)

The Definitive Fighter: In 2014, Capcom delivered what many consider the peak of modern 2D fighting with Ultra Street Fighter IV. It wasn’t just an update; it was the culmination of six years of iteration. Featuring 44 characters, five new fighters, rebalanced mechanics, and features tailored for tournament play, it became the definitive edition of the series. Ultra SFIV carried the competitive scene well into the next generation and solidified Capcom’s reputation as the master of the genre.

Conclusion

Few publishers have managed to keep their classic franchises alive while still evolving them for modern audiences. Entire genres have been shaped—or outright created—by its games, and many studios still borrow mechanics, pacing, and presentation styles first popularized by Capcom hits. Capcom’s roots in the arcade scene of the ’80s still echo in its design philosophy today.

Whether it’s the tight, responsive controls, the emphasis on replayability, or the focus on skill mastery, that “one more try” mentality is baked into their games. It’s a design ethos that has transcended generations, ensuring that even the newest Capcom releases feel instantly engaging, just like dropping a coin into a cabinet back in the day.